Kevin Musgrave and Jeff Tischauser

Introduction

On May 14, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, a group of torch-bearing individuals gathered to protest the removal of a statue of former Confederate leader Robert E. Lee. Proclaiming “all white lives matter” and chanting Nazi slogans such as “blood and soil,” the group was led by alt-right figurehead Richard Spencer. Calling upon a politics of white identity to decry the symbolic erasure of Southern history and culture, Spencer extolled that “what brings us together is that we are white, we are a people, we will not be replaced” (quoted in Vozzella 2017). Resonating with the rhetoric of the resurgent nationalism and anti-political correctness of the Trump administration, Spencer has utilized sharpening racial divisions to create alliances with mainstream conservatives and to help build a powerful political base. Importantly, however, such a convergence between US conservatism and far-right, white nationalist politics is not a new phenomenon. Signaling a long and complicated history of the interrelated nature of far-right racism, proto-fascism, and conservative traditionalism in the US, the incidents in Charlottesville provide an entry point for interrogating the ideological underpinnings and contemporary resurgence of radical conservatism under the guise of Spencer’s alt-right.

Undertaking a criticism of alt-right discourse we will define and critique the movement through its language, rhetorical forms, and lines of argument. In doing so we seek to make visible the ideological and theoretical underpinnings of the movement, to more properly situate the alt-right within the history of US conservatism, and to better understand the historical roots and contemporary iterations of white supremacist politics in the United States. While the alt-right exists in both online and offline spaces, has several prominent leaders, and contains differing political visions and social projects, we take the rhetoric of Richard Spencer as representative of the soft ideological core of the alt-right (see Hawley 2017).[1] As perhaps the most visible alt-right spokesman, leader of the National Policy Institute (NPI), and with Paul Gottfried, the coiner of the term alt-right, Spencer offers a clear image of the political aspirations of the far-right insurgent movement. Described by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) as an “academic racist” who utilizes his pseudo-intellectual works on Radix and elsewhere to “appeal to educated, middle-class whites,” Spencer’s academic style and approach also help to more clearly map the points of convergence between conservatism and neo-Nazism in the US (Southern Poverty Law Center nd).

Tracing the history and intellectual influences of Spencer and the alt-right, ultimately we argue that the alt-right is an outgrowth and logical extension of traditionalist idioms of conservatism in the US, particularly post-Cold War visions of paleoconservatism in the works of Paul Gottfried and Samuel Francis. To say that the alt-right is a logical extension of US traditionalist conservatism is not to say that it draws its influence strictly from US political thought. Rather, we argue that not only must we understand how US conservatism was born of European circumstances but that we must also understand the continuing influence of European, particularly French, far-right thought and movements on US conservatism. Spencer’s particular vision, then, is an admixture of European New Right thought with US paleconservatism, creating a unique articulation of far-right politics suited to the contemporary global, post-modern political climate while maintaining a distinctive American flavor.

Though the lineage is not entirely direct, one can nonetheless trace a jagged seam through various iterations of conservatism that gives rise to the racial nationalism and fascism of the alt-right from the early conservatism of Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre. Importantly, we are not arguing that we should collapse the distinctions between conservatism on the one hand and fascism on the other. Whereas conservatives have more traditionally been concerned with preservation as opposed to innovation or active revolution, fascism may be identified with a revolutionary-rightist or conservative position that seeks to reclaim, through violence and insurrection, a past thought lost or destroyed by the political left (see Burley 2017). Recognizing the significance of these distinctions, we nonetheless argue that fascism emerges from the history of conservatism, and thus bears family resemblances that cannot be ignored. These family resemblances remain present today, linking the alt-right with traditionalist conservatism. This position in some ways cuts against the grain of Hawley’s (2017) work on the alt-right, which claims that “It is totally distinct from conservatism as we know it” (4), and resonates more with the work of Corey Robin (2011) who argues that all conservatives and far-right thinkers and movements are united by a common “animus against the agency of the subordinate classes” (7). This is not to disregard the importance of Hawley’s work—for he also connects the alt-right to paleoconservatism and the European New Right—nor to overlook the nuanced differences among various articulations of conservatism that may be missed by the umbrella definition provided by Robin. Rather, it is to argue that, in fact, though the alt-right may differ from the traditionalism of the paleoconservative movement, it is nonetheless not as wholly distinct from it as one might think. Indeed, we argue that it is a logical, even if more radical extension of paleoconservatism as envisioned by Paul Gottfried and Samuel Francis, blended with the thought of German and French far-right thinkers and movements.

Our essay unfolds in five main sections. First, we provide a brief history of conservatism, from its birth as a reactionary response in France, Germany, and England to the liberalism of the Enlightenment philosophes and the violence of the French Revolution. Tracing a through line from early conservatives such as Joseph de Maistre to contemporary far-right conservatives in France, we demonstrate that French conservatism and far-right politics have been and remain crucial to understanding American conservatism and the alt-right of Spencer. In sections two and three, we undertake a similar history of US conservatism, paying particular attention to the Old Right and traditionalist idioms of conservatism and the paleoconservative movement, connecting this intellectual strain of the US right to those continental thinkers who came before them, as well as to the alt-right. Section four provides a criticism of alt-right discourse by attending to the rhetoric of Richard Spencer. Deconstructing his arguments regarding the biological nature of racial difference, the imperatives of identitarianism and metapolitics, and the call for a white ethno-state in the US, we demonstrate both the resonances of traditionalist conservative thinkers from France, Germany, and the United States, as well as the ways in which Spencer co-opts and inverts so-called cultural Marxist theory to buttress his white privilege politics. Finally, we conclude by discussing the larger theoretical and historical takeaways of our essay, suggest lessons for opposing alt-right rhetoric in the public sphere, and call for conservatives to be more critical and reflexive regarding how best to excise far-right ideologies from within their ranks

Conservatism’s European Roots

To understand the contemporary importance of the alt-right we need to first understand its history and complicated relationship with other articulations of conservatism. Indeed, the alt-right has not arisen in a political vacuum but rather is a product of conflicting visions of conservatism and various iterations of conservative traditionalism in the US and abroad.

Emerging primarily as a reactionary movement against the perceived atheist humanism of the French philosophes and the subsequent Revolution in France, conservatism offered an alternative vision of modernity that retained a commitment to the religious monarchy and organic social order of the ancient regime. As a broader discourse, conservatism emphasizes difference and division as a means of critiquing the limits of Enlightenment reason. As Zeev Sternhell writes, conservatism emerged to offer a different vision of modernity than that of the Enlightenment. Revolting “against rationalism, the autonomy of the individual, and all that unites people” (2010, 7-9), the modernity articulated by the anti-Enlightenment conservatives was “based on all that differentiates people—history, culture, language” and sought to create “a political culture that denied reason either the capacity or the right to mold people’s lives, saw religion as an essential foundation of society, and did not hesitate to call on the state to regulate social relationships or to intervene in the economy” (8). In this way, Sternhell paints conservatism as a radically historicist discourse that emphasizes particularity, plurality, and difference as a means of preserving social hierarchy.

These ideas took influence from the counter-Reformation that came before it, while adapting arguments against the Reformation to comport with a more modern set of exigencies bent on maintaining religious authority in the face of the equalitarianism of the philosophes. Indeed, the counter-revolutionary right understood philosophy as the logical outcome of fundamental changes to French values and culture, beginning with the Reformation and culminating in the bloodshed and violence that marked the Revolution. This anti-Revolutionary sentiment remains a central component of far-right conservatism today, illuminating Peter Davies’ claim that “Counter-Revolution is not just a period, but an idea” that has “remained a battleground throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and into the twenty-first” (Davies 2002, 28). Significantly, as we will demonstrate, the counter-Revolutionary spirit, much like the Enlightenment it opposed, was not confined to France but spread around the globe, adapting itself to local cultural circumstances and political structures (see Berlin 2001; McMahon 2000; Sternhell 2010).

For instance, in Germany, historians and critics have traced a lineage of conservatism in the aesthetic nationalism of Johann Gottfried Herder, the philosophical idealism of G.W.F. Hegel, the cultural criticism of Friedrich Nietzsche, and the proto-fascism of the German Romantics of the Bayreuth circle, particularly Richard Wagner. Likewise, German conservatism was given a more radical, fascist orientation after the First World War with the conservative revolution that included the likes of Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, and Carl Schmitt among others. Though there are undoubtedly great differences between Herder, Hegel, Nietzsche, and Wagner, not to mention Carl Schmitt, these thinkers offer common criticisms of the instrumental rationality of Enlightenment liberalism, the mechanistic and materialistic logics of the radically autonomous individual, and the historical rootedness of a people within a given cultural and linguistic system.[2] Inflections of this critique of liberal economism in German thought can be found in left-leaning political thought, as well, for instance in the criticism of mass society found in Ferdinand Tonnies, Max Weber, and Jurgen Habermas. What separates the left from the right, however, is largely a commitment to Enlightenment ideals rather than their denunciation in defense of an organic vision of a stratified and hierarchical social order.

While German thought offers a particular iteration of conservatism tailored to its history and culture, so too does England, primarily in the counter-revolutionary thought of Thomas Hobbes, the writings of Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and most notoriously Edmund Burke . Indeed, Burke is a central figure in the history of conservatism in the Anglo-Saxon world, becoming a great inspiration in many regards for the development of conservatism in the United States. Russell Kirk, a prominent conservative intellectual in the US, deifies Burke in the pantheon of conservativism, arguing that it was Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France who “defined in the public consciousness, for the first time, the opposing poles of conservation and innovation” (1953, 5). In this way, Burke was responsible for the birth of something like modern conservatism as a conscious and self-aware political position. Distinguishing between the “aristocratic liberalism,” rebuke of “equalitarianism,” and defense of legal order that undergirded Burke’s conservatism and the metaphysical abstractions of Hegelian and German idealism, for Kirk only Burke can wear the mantle of the true conservative (13).

A pragmatic statesman, rigid parliamentarian, and reluctant theorist, Burke voiced his concerns about the spirit of the Revolution and its promise of social levelling from a uniquely British perspective. Writing against the Revolution in France, Burke condemned with ferocity claims regarding the “rights of man” and the mechanistic rationalism of the philosophes that he viewed as leading naturally to the violence, bloodshed, and destruction of institutions of French civil society. Appealing to natural and divine order, for Burke the equalitarianism and levelling of the Revolutionary spirit would destroy social order and stability, as well as nullify the eternal contract between those who are deceased, the presently living, and those yet to be born. Society, from this perspective, is a delicate organism that binds together all persons in a harmonious contractual relationship perfectly designed and authored by God. To meddle with its inner-workings, to render it susceptible to human fancy and whim, and to reduce to rubble its institutions is thus to go against the wishes of providence. The act of Revolution here is figured as voiding the contract between God and man, consecrated in the office of the king, and also as uprooting society and tearing apart its very fabric. As Burke (1966) claims, the “levelers therefore only change and pervert the natural order of things; they load the edifice of society, by setting up in the air what the solidity of the structure requires to be on the ground” (61). The Enlightenment of the French Revolution, then, renders impossible any sense of stability and order to the affairs of government, replacing tradition and the supposed wisdom of prejudice with continual progress and a cold, scientistic rationalism. Conservatism in Burke thus emerges as a means of preserving and conserving traditions and established political order from reckless innovation and calls for egalitarian social leveling.

Not confined to a simple political nostalgia, however, the early Right was much more sweeping in its critique of the liberal Enlightenment’s vision of modernity. Writing on the emergence of the political Right, Darrin McMahon (2001) reaches a similar conclusion, arguing that “the early Right was in fact radical, striving far more to create a world that had never been than to recapture a world that was lost” (14). This latent radicalism of the conservative early Right was perhaps captured most vociferously by Joseph de Maistre. Born to an aristocratic family in Chambery, Maistre’s father was a Judge on the high court, and Maistre followed suit, attaining a degree in law. A committed Catholic monarchist, Maistre was abhorred by the Enlightenment liberalism of the philosophes, seeing it foremost as a “satanic revolt” against God’s divine order (see Lively 1971, 9). Influenced by the writings of Burke, Maistre often took Burkean insights to their extreme, castigating the very idea of democracy as farce, repudiating the abstract principle of rights without duties, and proclaiming the inherent virtues of violence and prejudicial irrationality.

Viewing the violence of the Revolution as a form of providential retribution for the hubris of man, death functioned for Maistre as national regeneration through corporal punishment. Illustrating this providential view of the Revolution, Maistre (1971) argues that “when the human spirit has lost its resilience through indolence, incredulity, and the gangrenous vices that follow an excess of civilization, it can be retempered only in blood” (62). Utilizing the metaphor of the tree to emphasize both the organic nature and rootedness of society in a natural order, Maistre articulates this regenerative bloodshed as akin to pruning by the divine hand of God. For just as a rose bush needs to be properly pruned and cared for in order to ensure its vitality and blossoming in the coming season, society, too, must be ridded of its excesses in order to assure its continued health and well-being (62).

Rooted as society is in religious and cultural custom, it also dependent upon an earthly sovereign for its continued security and stability. In this way, society is constituted by a sovereign, and a people owe their existence to this sovereign power much as a hive to its queen (de Maistre, 98). Arising from the natural relationship of sovereignty and society is the nation itself, which Maistre portrays as possessing “a general soul and a true moral unity,” which is “evidenced above all by language” (99). The personality of the state, embodied by its ruler, and its particular form of government, is a product of this moral unity. This leads Maistre to proclaim that “From these different national characteristics are born the different modifications of government,” and that to impose a universal mode of government upon all peoples and nations is to do violence to their inherent moral character and cultural customs (99). It is for these reasons—the primacy of sovereignty to society, the particular moral characters of nations, and the maintenance of ethno-cultural pluralism—that Maistre opposes the democratic Revolution of the French Enlightenment. Indeed, these principles led Maistre to denounce democracy as an idea, for as he maintains one cannot have a nation, a people, or any form of political stability without the anterior existence of the sovereign, while the heart of democracy, as Maistre describes it, is an association of men governing themselves in the absence of a unified sovereign (127).

While there are many ways of reading Maistre’s works, it is significant that many find in his writings early strains of something resembling a latent fascism. For instance, while we may identify resonances between Maistre’s arguments and the relatively moderate positions of Burke, we may also identify a more radical set of ideas that influenced subsequent far-right thinkers in France and beyond. Writing on this tendency, Lively (1971) argues that Maistre’s fetishization of violence, his rebuke of the autonomous individual, and his glorification of sovereignty provides more than enough textual evidence to warrant an “interpretation of Maistre as one of the first in the modern fascist tradition” (7). Thus, while some may read Maistre as a more moderate conservative concerned with social order and cohesion, we may not simply wish away his more radical tendencies. It is doubtless that for these reasons that someone like Kirk seeks to so ardently distinguish Burkean conservatism from German and French articulations of Right-wing conservatism, as it provides a way of drawing firmer boundaries between conservatism on the one hand and fascism on the other. While there are certainly important distinctions between the two, a point we will return to in our conclusion, we maintain that we may nevertheless find in the early-Right and its counter-Revolutionary spirit a common line of argument that connects these thinkers to present day far-right ideologies and to Richard Spencer more specifically.

Indeed, stemming from Maistre’s early defense of monarchical rule, religious order, and the ancient regime, the subsequent development of a newer French Right was found in the populist appeals of Georges Boulanger, Maurice Barres, and Charles Maurras. Writing on the rise of this amorphous far-right populist strain of French politics, Davies (2002) argues that the “Franco-Prussian War and the birth of the Third Republic had brought a political realignment, and nationalism transferred from left to right a whole combination of ideas, sentiments, and values. In fundamental terms, the nation had replaced traditional religion as the focal-point of far-right discourse” (78). This growing concern with nationalism as opposed to the monarchy, as well as populist appeals to popular sovereignty rather than a defense of the aristocracy on the far-right, drew from and reinvigorated fascist ideologies in France in order to combat the bourgeois humanism of the Third Republic.

Significantly, however, it was not just the far-right that challenged the liberal humanism of the Third Republic following the War. Indeed, as Stefanos Geroulanos (2010) meticulously demonstrates, a “battleground of humanisms” emerged in France after the War which saw Communists, Catholics, and political non-conformists, alike, offering alternative visions of a post-humanist anthropology capable of dealing with the failings of political liberalism (28). Significantly, this assault on bourgeois humanism from across the political spectrum in French political and intellectual culture was heavily influenced by leading thinkers of the German Conservative Revolution, particularly the work of Martin Heidegger (Geroulanos 2010). Thus, the far-right and the far-Left borrowed from one another and exchanged ideas in the creation of a Third Way political position that called for a reinvigorated nationalism and the birth of a “New Man” that emphasized the rootedness of the individual. These calls for national and intellectual rebirth often verged on a kind of “spiritual fascism” which grounded many reactionary and counter-Revolutionary movements in France (Geroulanos 2010, 123).

This kind of spiritual fascism was perhaps given its clearest articulation by Charles Maurras, founder of Action Francaise (AF), a monarchist and anti-Semitic movement that emerged from the tribulations and political turmoil of the Dreyfus Affair. Evincing the admixture of far-right and far-Left thought that marked the inter-war period, Maurras’s project married together nationalism, non-Marxist iterations of socialist economic thought, and populism refracted through a Darwinian understanding of the nation as a vital organism—one that was under attack by a virus of a growing non-rooted Jewish population, communism, and republicanism. Thus, what emerges in Maurras is “an unusual synthesis of de Maistre’s conservatism, Barres’ nationalism, and fin-de-siecle revolutionary syndicalism” that undergirded a proto-fascist vision of a reinvigorated monarchy couched within a rhetoric of civic nationalism (Davies 2002, 86). Far-Right proto-fascism did not end with Maurras and the AF, however, finding its doctrines extended and altered in the collaborationist policies of Petain and Laval’s Vichy Regime during the Second World War, by the French Algerian movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and the formation of the Front National (FN) by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972. Though each of these movements is distinct in their goals and aims, they maintain significant political and ideological overlap in their commitment to moral order, a fear of national decadence and decline, and the call for national rebirth and regeneration. Indeed, Le Pen–a former supporter of Maurras’ AF and member of the Poujadist movement for a French Algeria—and his FN party has become a bastion of far-right politics in France. Writing on the nature of the FN, Davies (2002) states that it is “a coalition of interests,” that is composed of “Neo-fascists, hardened Algerie Francaise veterans, ex-Poujadists, new right activists, disillusioned conservatives, integrist Catholics,” and others who found in the party a new ideological home amid the shifting political grounds of the 1970s (125). Maintaining similar concerns and principles of other far-right movements before it, FN discourse prioritizes nation and identity as its primary points of emphasis.

These emphases have remained central to the FN, yet other far-right actors once affiliated with the party have fractured from its rank and file membership, founding other, more extreme far-right groups that bring together identity and nationalism in a rhetoric of identitarianism. Central amongst these individuals are Alain de Benoist, founder of the extreme Right group the Research and Study Group for European Civilization (GRECE) and GRECE defector and radical conservative intellectual Guillaume Faye. Benoist, a former journalist and intellectual, established a theoretical project premised upon the concepts of ethno-pluralism and organic democracy, which taken together formed an alternative vision of modernity that drew from the wisdom of tradition and Western culture in order to articulate a vision of democracy not tethered to egalitarianism or libertarianism, but rather to the notion of fraternalism. Indeed, fraternity, the supposedly forgotten piece of the triptych of Revolutionary democratic aspirations, provides for Benoit a way of reimagining democracy in a post-modern, globalized, pluralistic moment.

Opposed to direct democracy, to (neo)liberal democratic projects, and to the social democracy of welfare state politics, organic democracy returns to classical Greek understandings of democracy and re-appropriates, “adapting to the modern world—a notion of people and community that has been eclipsed by two thousand years of egalitarianism, rationalism, and exaltation of the rootless individual” (Benoist 2011, 29). Drawing from traditional conservative critiques of liberalism, Benoist recognizes the radical particularity, historically embedded, and linguistically bounded nature of a people in order to argue for the inherent differences between ethnic groups and nations. It is from this idea that Benoist elaborates his principle of ethno-pluralism, the Maistrean notion that each people or nation possesses a distinct national and moral character which must be protected against the universalism of liberal thought and economic imperialism. Yet, while pluralism of peoples and cultures is a good to be protected and valued, pluralism within the bounds of the nation is an enemy to be guarded against. As Benoist claims, “Pluralism is a positive notion, but it cannot be applied to everything. We should not confuse the pluralism of values, which is a sign of the break-up of society, with the pluralism of opinions, which is a natural consequence of human diversity” (70-1). Pluralism of values stems naturally from the distinct culture, history, and language of a people, such that multicultural societies themselves, and state policies that encourage diversity and inclusion, set the stage for their own dissolution by encouraging the proliferation and confrontation of radically opposed value systems in the heart of society. Thus, the only viable democratic vision for Benoist is an organic democracy capable of allowing “a folk community to carve a destiny for itself in line with its own founding values” (71). Fraternity, in this sense, stresses the familial and spiritual nature of community and ethnic identity, placing belonging to the nation within the realm of biological and folk understandings of shared heritage.

A former member of GRECE and associate of Benoist, Guillame Faye’s work carries clear resonances of organic understandings of identitarian democracy. However, Faye, along with fellow far-right intellectual Piere Vial, left the think-tank as they perceived Benoist’s commitments to extremist far-right principles began to waiver. Likewise, Benoist has since critiqued the extremism and political aspirations of Faye’s so-called archeofuturist project. Drawing inspiration from the intellectuals of the German Conservative Revolution of the 1920s and spiritual fascism of Italian theorist Julius Evola, Faye’s archeofuturism maintains that we are living in a world of convergent catastrophes that will ultimately destroy the contemporary global political-economic order. Proclaiming that “Modernity has grown obsolete,” and humanity is presently “living in the interregnum” between political regimes (Faye 2010, 12, 28), the only solution for Faye is to turn to an archeofuturism that “envisage[s] a future society that combines techno-scientific progress with a return to the traditional answers that stretch back into the mists of time” (27). Such a project demands political revolution and restoration, with revolution understood ultimately as an act of restoration in and of itself. Such a temporality moves away from liberal understandings of linear progress and toward a spherical temporality premised upon Nietzsche’s eternal return of the same (44).

Indeed, Nietzsche figures prominently in Faye’s work as he demands a post-human epistemology that embraces an “inegalitarian philosophy of will to power” in order to overcome the supposedly emasculating philosophy of universal tolerance and compassion of the discourse multiculturalism (65). This is imperative for Faye, as multiculturalism, much as in Benoist, paves the road to national dissolution and global disorder in an era of shifting geopolitical realities. An age in which tired arguments of East v. West no longer hold, Faye proclaims that the new geopolitical order pits North v. South, with Islamic cultures posing the greatest threat to European civilization and White identity. However, it is not enough to identify a common enemy of European culture—the shortcoming of Schmitt’s philosophy according to Faye—but to in fact create a recognition of political friendship. This positive “spiritual and anthropological” project places identity at the center of politics, and moves identitarianism into a metapolitical theoretical position. This is to say that before one becomes concerned with ideological or doctrinal differences one ought to recognize a shared worldview that is rooted in a spiritual and anthropological identity which constitutes them as an organic folk. It is only after this organic folk gains political self-awareness that the archeofuturist project of the creation of a new European federal empire can be created as a power-bloc of geo-political force and ethnic solidarity against the global south. As we will demonstrate later, this line of argument is taken up by Spencer, anchoring the alt-right in a soft, pseudo-intellectual ground regarding the primacy of racial identity in contemporary politics. Significantly, this point is ultimately reached, yet through a different trajectory, by Spencer’s other primary influence—the US paleoconservative movement.

A Budding US Conservatism

While we can trace a genealogy of far-right thought in France from the traditionalism of Maistre, likewise we maintain that we can trace a through line from a nascent conservative attitude in the early days of the US Republic through to the alt-right. Significantly, this history demonstrates that conservatism cannot simply be understood as a unified historical movement, but as Paul Gottfried and Thomas Fleming (1988) argue, as a series of movements that at times conflict with one another regarding the proper relationships among individuals, community, industry, and government. Rather than speak of a unified vision of conservatism in the US, then, we will speak of various conservatisms that at times conflict and at others converge with one another.

Such a family history of conservatism in the US is offered by Russell Kirk in his momentous 1953 text The Conservative Mind. Describing the American Revolution as born of conservative principles, for Kirk conservatism first comes to the shores of the Atlantic from the works and speeches of Burke and his exchanges with Thomas Paine on the nature freedom, rights, and democratic self-rule. As Kirk (1953) writes, Burke “had set the course for British conservatism, he had become a model for Continental statesmen, and he had insinuated himself even into the rebellious soul of America” (12). This conservative spirit of rebellion he then follows from the rule-of-law conservatism of John Adams, the romantic conservatism of George Canning, the southern conservatism of John C. Calhoun and John Randolph, through to the so-called critical conservatism of Irving Babbit, Paul Elmer More, and George Santayana. A larger umbrella that encompasses a host of ideological and philosophical positions as wide as pro-slavery arguments regarding state’s rights to pragmatic metaphysics, conservatism for Burke is a flexible “working premise” that at bottom maintains a core belief in the idea that “society is a spiritual reality, possessing an eternal life but a delicate constitution,” and as such is something that “cannot be scrapped and recast as if it were a machine” (7). While conservatives could agree on this basic premise, there were many other issues that created conflict in early US conservative discourse, namely a conflict between the Federalism of the north and the Southern strand of conservatism that sought to maintain agrarian life and an independent political authority.

This rift within the heart of the early conservative spirit in the US remained a polarizing force into the twentieth century, when conservatism bloomed into not simply a rebellious spirit in US politics but into a full-blown insurgent political force to combat the New Deal policies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Phillips-Fein 2010). While the New Deal did not do away with the fissures and cleavages that marked the conservative Right, it did however unite a vast array of intellectuals committed to defining, defending, and conserving more traditional systems of thought against the centralizing forces of technocracy, managerialism, and state power. A reactionary force bent on fighting the perceived creeping statism and egalitarianism of the social welfare state, the conservative movement brought together a traditional, Old Right consisting of Southern conservatives and monarchists one the one hand and a budding libertarian New Right on the other, in order to defend principles of law, order, and decentralized government (Rothbard 1994).

Indeed, as Michael Lee (2014) has argued, from its very inception, conservatism in the US has consisted of competing argumentative frames that have produced fusion and fracture at different historical moments. Conceiving of conservatism as a political language with which to create and describe society, Lee maintains that this language consists of both libertarian and traditionalist dialects. Holding between them inherent contradictions, conservatism’s dialects embody a larger prescriptive dialectic between embracing modernity and returning to pre-modern modes of life. Stemming from deep-rooted, conflicting epistemological and ontological viewpoints on history, human nature, and rationality, the libertarian and traditionalist dialects consist of opposing value systems and rhetorical “God-terms” to organize their political projects. While libertarian conservatives stress the importance of concepts such as “freedom,” “liberty,” “reason,” “individual,” and “markets,” in the continued development of modernity and unfettered capitalism, traditionalists emphasize the centrality of “tradition,” “hierarchy,” “order,” and “transcendence” to social cohesion and stability in the face of change (Lee 2014, 43).

Of particular interest to us in this essay are those traditionalist conservatives of the US Old Right. While those on the libertarian Right have largely become synonymous with conservatism in the US, the traditionalist dialect has re-emerged as a legitimate political force since the close of the Cold War. Drawing their inspiration from Burke and others, post-War traditionalists such as Kirk had been largely committed to isolationism, nativism, and Americanism throughout the Second World War, with some openly embracing biologically deterministic theories of white racial superiority, anti-Semitism, and pro-Nazi ideology (Bellant 1991; Diamond 1995, 22-25).

Writing on the origins of conservatism and the defining principles of the Old Right, Sara Diamond (1995) portrays this diverse group of intellectuals as men who “viewed with trepidation the expansion of the welfare state and some seemingly related trends: racial minorities’ nascent demands for civil rights, the spread of secularism, and the growth of mass, popular culture” (21). Not simply detesting the increasing power of the state over individual freedom, US conservatism also feared progressive policy measures from Reconstruction onward that sought to radically level hierarchies of race, class, and gender that were thought to be part of the natural order of an organic conception of white, Western culture.[3]

Representative of this Old Right traditionalism are writers such as Eric Voegelin, Russell Kirk, and Richard Weaver. Grounding conservatism in neo-Platonist conceptions of transcendent, metaphysical truths regarding the wisdom of tradition, history, and ancestral knowledge, Kirk (1989) writes in his essay entitled “The Question of Tradition,” “The traditions which govern private and social morality are set too close about the heart of a civilization to bear much tampering with” (63). To Kirk tradition represents a transhistorical contract that binds past, present, and future, standing as “transcendent truth expressed in the filtered opinions of our ancestors” (63). Searching for a higher order based on spiritual bonds to guard against the decadence and rootlessness of the modern world, tradition, for Kirk, represents a spiritual bedrock upon which cultures create natural social structures of political governance. Attempts to legislate against economic inequality, to level racial disparities, or to encourage women to enter into the workforce tamper with this spiritual bedrock, untethering us from traditional wisdom and social structures, leading a path toward decadence and decline. In this sense, as Corey Robin argues, conservatives see in liberal policies and democratic movements “a terrible disturbance in the private life of power” that disrupts the supposed natural order of the social world (13).

Though a prominent line of conservative thought throughout the 1940s and 1950s, traditionalism faded into the background in the political landscape of the 1960s and the burgeoning politics of the Cold War. The post-War effort, primarily on the libertarian Right, to transform conservatism into a broad coalition that sought political victories and action, rather than intellectual cohesion saw the retreat of the intellectual treatises of Kirk and others. Additionally, the identification of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater as the conservative candidate to challenge liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller rebranded conservatism with libertarian principles of free trade in the minds of the broader American public. Thus, as Gottfried and Fleming (1988) note, though the 1964 campaign of Goldwater placed conservatism within mainstream political discourse, it also proved detrimental to the movement by reducing conservatism to a narrow social philosophy of free markets and a pragmatic politics that eschewed intellectual rigor. Led by individuals such as Phyllis Schlafly, Paul Weyrich, and most notably William F. Buckley, this New Right network created a vast array of think tanks, magazines, and other print media that nonetheless sustained American conservatism in the mid-20th century.[4]

Coalescing ideologically on principles of combatting domestic democratic movements for social equality, fighting the spread of communism at home, and spreading the gospel of liberal democracy abroad, a rough consensus was formed that united conservatives, old and new, in a battle against the perceived threats of a growing state apparatus that threatened individual liberty and communal authority. Capable of articulating the economic, cultural, and spiritual concerns of conservatives across the spectrum, Ronald Reagan proved capable, at least tenuously, of fusing the libertarian and traditionalist dialects of conservatism. Uniting the conservative vanguard and the Republican Party against communism through his rhetorical prowess, Ronald Reagan rose to political prominence, and gained the presidency in 1981. Yet, as Diamond (1995) has argued, if Reagan represented a moment of conservative fusion and ushered in a neoconservative consensus throughout the 1980s, “The end of Soviet-style Communism coincided with the Right’s renewed focus on traditional moral order and ethnic-cultural homogeneity inside the borders of the United States” (2). Championing an intellectual backlash against neoconservative and libertarian philosophies, a group of committed paleoconservatives called for a renewed commitment to traditionalist concerns.

Paleoconservatism and the Return to Conservative Roots

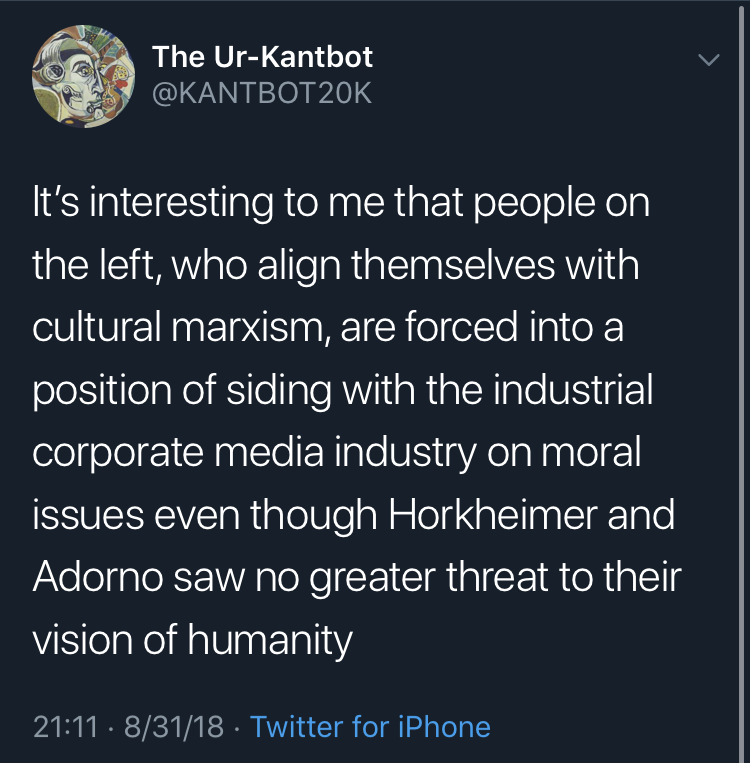

The renewed focus on tradition was the product of a careful campaign by a group of self-identified paleoconservative intellectuals that were unhappy with conservatism’s abandonment of its foundational philosophical commitments. Writing to this effect, paleoconservatives Paul Weyrich and William Lind (2009) argue that “one of the casualties of the Bush administration was the conservative movement” (134). Having become recalcitrant in its political successes throughout the 1970s and 1980s, post-Cold War Republican conservatism left behind many of its founding principles in an embrace of consumerism and global free-markets. Returning to and radicalizing the traditionalist idiom of conservatism championed by Kirk, the paleoconservatives refit traditionalism to a new set of political realities, targeting the so-called globalism and cultural Marxism of the left as the primary enemies of a Western, Judeo-Christian culture in decline. An amorphous and seemingly all-encompassing ideological assault on the West, paleoconservatives find the origins of cultural Marxism in the critical theory of the Frankfurt school, whose intellectual project they argue has taken over academia, the entertainment industries, and the state itself (see Weyrich and Lind, ch. 2). Striving to move beyond politics, to undo the cultural revolution of the 1960s, and to restore traditional American values, paleoconservatives understand themselves as in a war for the very existence of Western culture.

Led in many regards by long-time conservative figure and former member of both the Nixon and Reagan administrations Patrick Buchanan, the paleoconservative camp had its political headquarters in the Rockford Institute, a traditionalist think tank in Rockford, Illinois. Producing and distributing a monthly magazine entitled Chronicles of Culture, the Rockford Institute was founded by Thomas Fleming. Fleming, like many in the paleoconservative camp, was a professor of the humanities and an acolyte of Kirk (Diamond 1995; Gottfried and Fleming 1988). Denouncing the supposed end of ideology espoused by Francis Fukuyama and other neoconservatives, these paleocons saw in the heightened attention to the “political issues of morality, security, and nationalism” in a post-Cold War climate a rallying cry for a renewed nationalism (Dahl 1999, 7).

Dressed in the guise of Right-wing populism, Buchanan’s (1998) America First politics and his economic nationalism rebuked the supposed triumph of liberal democracy and its narrow association with free-market capitalism. Critiquing large, multinational corporations and the structures of late capitalism, Buchanan advocated for economic protection of vital industries, fixed markets, and protective tariffs to maintain a competitive US economy in a globalizing world. Ushering in an era of global free trade, it was the Cold War mission of exporting liberal democracy abroad that led to the slow erosion of manufacturing jobs in the U.S; as Buchanan argues, “In the global economy, money no longer follows the flag. Money has no flag” (54). Taken further, the global economy of unfettered trade dissolves national bonds of loyalty and patriotism in the name of liberal cosmopolitanism. An extension of traditional conservative and cultural nationalist critiques of the Enlightenment, Buchanan adds that “Free trade ideology is thus a product of a shift in perspective, from a God-centered universe to a man-centered one” (201). Cast as a logical extension of French Enlightenment sentiments, global free trade is an assault on the nation and on traditional Western values. What a post-Cold War political culture illustrated, Buchanan maintained, was that politics was less about a divide between left and right, capitalism and communism, and more so about nationalists and the liberal globalists.

If the dog-whistle of Buchanan’s calls for a new economic nationalism was carefully masked in a veneer of middle-class protectionism, other paleoconservatives have drawn from Old Right lines of argument that more explicitly invoked biological notions of racial superiority. For example, in his book Alien Nation, Peter Brimelow (1995) espouses openly nativist and racist arguments regarding the assault on the supposedly inherent white ethnic core of American national identity. Conceiving of the nation as “an ethnocultural community that . . . speaks one language,” Brimelow calls for a return to a white tribalism to defend western culture from state-sanctioned erasure (203). Though the sovereignty of the nation, the customs of western civilization, and the white ethnic core of the US are under attack from many angles, for Brimelow the primary driver of these problems is immigration policy. In his formulation, post-1965 immigration policy is inevitably leading to an “ethnic revolution” in which efforts at racial equality are rendered a power grab to subvert the historical legacy of white racial hegemony in the US (203). Eschewing the colorblind and post-racial narratives of the center-Right establishment of the Republican Party, Brimelow embraces whiteness as a marker of political identity. Within his recognition of whiteness, race is conceived of as biological, naturalizing the separation of cultures and knowledges. As he renders whiteness a visible political position in debates on immigration, there’s an explicit rejection of the structural inequalities that shape opportunities for newly arrived non-white immigrants. Instead, Brimelow acknowledges structural barriers that limit opportunities for white Americans and uses overtly racial arguments on culture and behavior to explain the criminal nature of immigrants of color.

Within Buchanan and Brimelow’s critiques of the welfare state and immigration policy is an implicitly proposed solution of crafting a middle-American white identity politics capable of challenging the hegemonic center of US politics. Articulating these concerns and potential solutions in a more precise and academic tone, Paul Gottfried and Samuel Francis have called for a conservatism that would move beyond preservationism toward a revolutionary cultural and racial populism. This paleoconservative move to an explicitly racial rhetoric ties together opposing forces in white racial ideology, and highlights what Omi and Winant (2015) define as the ‘racial reaction’ among whites since the advent of the civil rights movement. In Omi and Winant’s view, white racial reaction draws from racial ideologies that, depending on the context, recognize and erase racial difference and works to undercut the political successes of the civil rights movement. Paleoconservatives blur rhetorical lines and bring together recognition and erasure simultaneously, using traditionalist appeals to veil the contradictions embedded with their arguments.

As seen in the paleoconervative call to fortify the racial and cultural makeup of the US, their recognition and erasure of racial difference is undergirded by a glorified view of Western culture. In what can be taken as a two-part work on the loss of bourgeois culture, a sense of ethnic heritage, and localized self-government, Paul Gottfried’s After Liberalism (1999) and his Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt (2002) represent the evolving politics of the paleoconservative position. Offering a narrative of decline of national sovereignty, regional cultures, and western society at the behest of a global managerial “new class,” Gottfried argues that a commitment to Enlightenment ideals of rational planning, global cosmopolitanism, and open borders are destroying Western culture.

In his trenchant, if misguided, works of academic critique, Gottfried maintains that liberalism’s original architects held “deep reservations about popular rule” (39). Taking liberalism to be a unique cultural product, not simply a set of abstract theoretical principles and commitments, Gottfried argues that liberalism “designates not just liberal ideas but also their social setting” and political context (35). This cultural context and heritage, as Gottfried alludes to, is found in a bourgeois political culture that maintained a sense of hierarchy in the face of demands for radical egalitarianism. This primordial sense of liberalism, however, has been eroded and ultimately lost in the name of liberal democracy, technocratic reason, and state planning.

Giving rise to the modern, managerial welfare state, liberalism’s demise was driven not primarily by economic forces nor by laissez-faire values and policies, but by a cultural logic of multiculturalism. Assuming that cultures are incompatible and engaged in a zero-sum game for survival, these attacks against multiculturalism also presume that people of color “are actually, or even disproportionately benefiting from its [multiculturalism’s] experimental largess” (Lentin and Titley 2011, 110-111). For example, Gottfried (2002) uses the rhetoric of atonement and guilt to argue that multiculturalism is indicative of a logical progression of liberal Protestantism that fashions slavery as the original sin of white Americans. Culminating in a secular religiosity that debases theology and feminizes Christianity, Gottfried claims that multiculturalism is the product of a “fusion of a victim-centered feminism with the Protestant framework of sin and redemption” (56). Domestically, pluralism legitimates the managerial state’s efforts to impose a doctrine of political correctness, and is said to divide society into victims and victimizers. Globally, pluralism warrants, in the name of the welfare state, open borders for trade, lax immigration policies, transnational bureaucracy, and a global mission to make the world safe for democracy, ultimately eroding national sovereignty and the decline of Western society in pursuit of a cosmopolitan agenda (78-88).

The answer for combatting the so-called therapeutic welfare state, for Gottfried, lies in a resurgent Right-leaning populist nationalism. This program entails an “identitarian politics and appeals to a cultural heritage,” premised upon a “traditional communal identity” (Gottfried 2002, 118). Additionally, Gottfried sees hope in the emergent European “postmodernist Right,” and its political ideology of ethno-pluralism which “speaks on behalf of the distinctiveness of peoples and regions and upholds their inalienable right not to be “culturally homogenized” (129). His political project entails a rejection of Enlightenment notions of a rational world government in defense of localized, communal traditions and shared ethnic identity rooted in bourgeois culture.

Arguing in a similar vein, Samuel Francis, in his collected volume of essays entitled Revolution From the Middle (1997), paints a picture of what he calls Middle American Radicals (MARs) that have been left behind by the welfare state. The culmination of Nixon’s Southern Strategy, MARs are described by Francis as the former “backbone” of George Wallace’s political constituency, as well as a combination of Reagan Democrats, and supporters of the candidacies of a broad swath of “outsiders” including Ross Perot, David Duke, Ralph Nader, and Pat Buchanan. Portrayed as a “combination of culturally conservative moral and social beliefs with support for economically liberal policies such as Medicare, Social Security, unemployment benefits, and economic nationalism and protectionism,” MARs represent a disaffected group of white, middle-class workers who feel they are being squeezed from above by a corporate and governmental managerial elite, and from below by an unassimilated and unassimilable lower class of migrant laborers and peoples of color that are wresting jobs, political power, and tax dollars from middle Americans (12). Calling again upon the Immigration Act of 1965, the act is cast as a publicly subsidized erasure of white, middle-American culture through the lowering of national borders that links together managerial policy leaders and migrant laborers through the force of state policy.

As an insurgent counter-force against the state, MARs seek to build a “Middle American counter-culture” that can “overcome the divisive, individuating, and purely defensive response offered by traditional conservatism and to forge a new and unified core from which an alternative subculture and an authentic radicalism of the right can emerge” (Francis 1997, 73). Largely driven by Rust-Belt states, MARs are bent on collapsing the center of US politics and creating a space in which a radical alternative may emerge. Creating a space for collective action in the form of a resistant, white ethnic community, MARs attempt to hold on to their political and economic power by defending what they view as traditional American values and culture.

Seeking to rearticulate conservatism as a political program devoted to the “total redistribution of power in America,” Francis urges his compatriots to look beyond traditional conservative canons. Indeed, Francis writes that “if the cultural right in the United States is to take back its culture from those that have usurped it, it will find Gramsci’s ideas rewarding” (176). Recognizing the primacy of culture to the development of political power and institutions, Francis calls for fellow conservatives to take lessons from the counter-cultural tactics of the left in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as far-right European politics, to engage in the frontlines of the war for cultural hegemony in the United States.

The shared philosophical and political commitments of Buchanan, Brimelow, Gottfried, and Francis derive from their shared commitments to Old Right conservative traditionalism, as well as a shared infrastructure of political and media outlets that link them not only with each other but with the rise of the alt-right. In 1999, Peter Brimelow founded the website VDare, a white-nationalist news site that publishes political and social criticism on contemporary public affairs. Affiliated with the site are Buchanan, Francis, and alt-righter Jared Taylor. Six years later, Francis co-founded, with William Regnery, the National Policy Institute (NPI). A white-nationalist think tank operating under the slogan “For Our People, Our Race, Our Future,” the NPI has taken up the call for a metapolitical, identitarian far-right conservatism in the US, becoming the ideological and political core of the alt-right under the leadership of Richard Spencer.

Spencer, who holds a Master’s degree from the University of Chicago and dropped out of a PhD program in European intellectual history at Duke University to lead the cause of the NPI, along with Gottfried, coined the term “alternative right” and has gained public notoriety as a figurehead of the movement. In 2012, Spencer founded Radix Journal, a publication that describes itself as publishing “original work on culture, race, tradition, meta-politics, and critical theory (About Radix Journal).” Comprised of three “interrelated components,” including “an online magazine, RadixJournal.com, a biannual print journal, and a publishing imprint,” Radix is operated by, and distributes writings through, the auspices of the NPI. Though closely affiliated with paleoconservative thinkers and institutions, Spencer’s vision seeks to push the American Right further by offering a radical conservatism that marries together US traditionalism with the archeofuturism of Faye, and the insights of the German conservative revolution in order to openly embrace white supremacy, vehement nationalism, and biological theories of race. If conservative traditionalists in the past have taken great pains to distinguish their cultural nationalist positions from the more far-right white supremacist groups they helped create, the alt-right under Spencer strips away all the rhetorical veneers of more mainstream conservatism in the creation of a radical conservatism.

The Alt-Right’s (Pseudo)Philosophical Core: Richard Spencer, Metapolitics, and Identity

Connecting paleoconservative traditionalism with the far-right thought of Benoist and Faye as well as German conservatism, the intellectual foundation of Spencer’s political project is metapolitics. A self-proclaimed fan of the work of Richard Wagner and German Romanticism, Spencer’s metapolitics is a nod to both the proto-fascism of the Bayreuth circle in late-nineteenth century Germany and to Faye’s archeofuturist identitarianism (Harkinson 2016). A kind of spiritual politics of myth—with myth understood here as a kind of “necessary faith, or inspiration, or unifying mass yearning”—metapolitics stood as a driving force of hope for the national racism of Germany. Consisting of an amalgamation of romanticism, the so-called “science” of race, a loosely defined economic socialism, and a faith in the mystical forces of the volk, the metapolitics of Wagner was crafted as a response to the political atomization and legal structures that marked modernization and liberal society (Viereck, 1941, 19). Likewise, for Faye, metapolitics becomes a way of placing racial and ethnic identity at the core of French rebirth, and as the primary means of combatting the spread of Islamic faiths and peoples from the global south.

A commitment to metapolitics for Spencer is thus a means of rhetorically positioning himself within the shared mythology of history, wisdom, and culture afforded by the “science” of race, while also standing as a call to continuing the evolutionary process and the dynamic becoming of white peoples across the globe. This emphasis in alt-right thought is placed front and center, as the NPI annual conference bares the Nietzschean title “Become Who We Are.” Yet if Wagner adapted his romanticism to the political atomization, economic displacement, and political crises of modernity, Spencer is recrafting romanticism and mixing it with French far-right thought in order to adapt its core tenets to the age of neoliberalism and global governance.in order to legitimize neo-fascism and white supremacist politics. This project, Spencer writes, requires a replacement of the political pragmatism that marks establishment politics with a “ruthless idealism” capable of radical, structural change (Spencer 2015a).

As Spencer argues elsewhere, “Politics is the art of the possible. But today the impossible is necessary. And the art of the impossible is exactly the reason our movement should exist” (Spencer 2015f). The art of the impossible, for Spencer, entails moving beyond the structures and strictures of political liberalism to a higher metapolitics regarding identity and racial biology. Indeed, Spencer writes that while “liberalism is about how and what, that is, it is about ‘rights,’ ‘procedures,’ and ‘mechanisms,’ with elected representatives tasked with making judgment calls,” identitarianism is “fundamentally about who (and not how). How a society is to be governed—whether it be a parliamentary democracy, dictatorship, constitutional monarchy, or any other form—is of secondary importance” (Spencer, 2016a). Metapolitics, then, is about a cultural project of consciousness raising, of crafting a narrative, or better, a myth that stands capable of unifying the race and comprising a general will for becoming something greater. An alt-right metapolitical project, thus, displaces questions of governance with questions of biology and racial difference.

This conception of racial biology leads Spencer to the concept of identitarianism. As the practical manifestation of metapolitics, identitarianism, as its name suggests, “posits identity as the center—and central question—of a spiritual, intellectual, and political movement” (Spencer 2015c). Moving not only beyond questions of left and right, it also seeks to move beyond the nation state, operating globally. Thus, importantly, Spencer argues that identitarianism “avoids the term ‘nationalism’ and its history and connotations. Indeed, one of identitarianism’s central motives is the overcoming of the nationalism of recent historical memory, which was predicated on hatred of the European ‘Other’ (2015c). Rooted in a pre-Boasian racial anthropology, Spencer’s identitarianism heralds the work of American eugenicist Madison Grant who championed a theory of Nordic racial biology as the primary agent of historical change. In this schema, the primordial sense of political identification and belonging is not bound by nation, but of shared history, blood, and ethnic identity. Repackaging his white supremacist politics in a kind of Pan-Europeanism, Spencer can avoid the label of white nationalism and its inherently racist connotations. Approaching a kind of white-internationalism, the shared mythological history of Nordic peoples is not confined by geography but is a kind of hereditary trait that transcends national borders in the creation of a latent, yet unifiable white racial family.

In the so-called race realism of his identitarianism, Spencer inverts constructionist theories of race making culture as a product of biology. Yet, when determining the borders of whiteness and of Nordic inclusion the racist and flawed nature of Spencer’s pseudoscience of race becomes strikingly clear. While race stands as the primary agent in historical development, the primary agent in the development of racial biology is comprised of a strange admixture of geography, culture, history, blood, and myth (Harkinson 2016). For Spencer, the white race is always in a state of becoming which is at once conditioned and shaped by ethnic heritage, cultural mores, genetics, space and place, and a tribalist sense of collective belonging. Spencer’s race realism, then, is not as static or deterministic as he would claim. Indeed, Spencer’s theory of race is a complex of seemingly conflicting ideas, ultimately comprising an inconsistent and non-developed articulation of the primacy of biology in the unfolding of history (Spencer 2015d). Importantly, however, the power of metapolitics lies not in scientific fact or rationality but rather in the irrational and symbolic powers of myth. To this point, the work of Fields and Fields (2014) illuminates the layers of authority embedded into Spencer’s arguments. Fields and Fields’ work suggests that Spencer’s rhetoric connects to the founding myth of America, the structure that preconditions our conscious or unconscious attitudes and behaviors about groups and individuals. In this sense, Spencer’s arguments are authoritative and made legitimate not because he stands opposed to mainstream political culture as an embattled organic pseudo-intellectual, but because his arguments resonate with the “mental and social terrain” of the US (Fields and Fields 2014, 19). This terrain is mapped by a magical belief structure, what Fields and Fields label ‘racecraft,’ which influences human action and imagination. Racecraft is the massage that kneads race and racism into American cultural consciousness through informal codes, rituals of power, ancestral ties, and blood. In this view, Spencer’s racial arguments and racism are embraced by conservatives, then, not only through supposed academic thinking, evidence, or scientific truths, but through irrational passions; an obligation to traditional spirit; a ritual that purifies American culture for white folks.

The rationalistic and reflexive nature of contemporary geopolitics thus stands as two factors in stymieing a revolutionary Right. Following Faye, Spencer calls for a pan-European movement, as struggles between the US and Russia are viewed by Spencer as a relic of an “Atlanticist” paradigm of politics that is outdated and ill-equipped to meet the demands of Post-Cold War politics. Viewing current US- Russia relations as a kind of familial infighting between two power blocs of European racial identity, Spencer writes that “the history of the 20th century has been a history of a long civil war, a Brother’s War” (2016d). Rather than calling for what he sees as a “petty nationalism,” Spencer sees the only way to save the certain demise of Western culture in a Pan-European project of preserving and protecting white masculinity (2016a).

This familial understanding of global politics offered by the alt-right also underlies Spencer’s and the NPI’s repudiation of NATO in a post-Cold War landscape. In a NPI published paper titled “Beyond NATO,” Spencer and the board of the NPI argue that “the geopolitical enemies that justified the creation of NATO—National Socialist Germany and the Soviet Union—have long since disappeared from the world stage,” and have been replaced by new enemies that threaten Western culture (The National Policy Institute 2016). In the realities of this altered political arena, Spencer writes that “‘Freedom vs. Socialism’ is no longer a useful model for describing the ideological and political divisions” of international affairs (The National Policy Institute 2016). Rebuffing claims of the end of ideology, Spencer posits that a new geopolitical rift has emerged that marks a radical split between the West and Islamic Terrorism, Turkish radicals, a Chinese economic superpower, and Mexican immigrants. Importantly, this reconfiguration fashions foreign threats as exclusively racialized non-Western others (Goldberg 2009; Hall 1997; Lentin and Titley 2011). These perceived threats to the Pan-European family necessitate, for the NPI, replacing NATO with a defense program premised on three principles: cooperation with Russia, a program of Western European revival, and recognition of common interests and threats among Western nations. These foreign policy measures are meant to help create a metapolitical consciousness capable of unifying white peoples globally against geopolitical threats.

Yet, the family figures centrally not only as a metaphor for understanding global politics, but also as the fundamental building block for a white tribal culture domestically. The family, here, is figured under the norms of a patriarchal heteronormativity that posits the stability of the institution of marriage as crucial to maintaining racial health. In an essay entitled “The End of the Culture War,” the Supreme Court ruling on gay marriage is portrayed as a further indication of the decline of Western culture. As Spencer writes, “Marriage must, indeed, be re-founded on a much more radical level than that imagined by the egalitarian ‘Religious Right’ and various ‘Constitutionalists;’ marriage must not merely be ‘between a man and woman;’ the family must become an integral part of the health of our race—of our charge to birth a strong, intelligent, beautiful, and productive people” (Spencer 2015e). In this formula, homosexuality is rendered unnatural and counterproductive to the continued evolution of the race. Indeed, homosexual behavior becomes biologically inefficient, a further usurpation of white masculine supremacy, and antagonistic to the metapolitical goals at the heart of identitarianism.

Dovetailing with lines of fundamentalist evangelicalism, this position proffers a deterministic understanding of the role of biological reproduction to the strength and preservation of the nation state. As Melinda Cooper (2008) demonstrates, evangelicals have long understood sexual politics and reproduction “to be a project of national restoration,” figuring unborn life of the fetus as a metonym for the potentially aborted future of the waning sovereign nation” (169). While both evangelicals and the alt-right deny agency and bodily autonomy to women in the name of the (re)production and maintenance of the nation, ultimately making “a claim to the bodies of women,” the alt-right does not advocate a right-to-life political stance (Cooper 2008, 171). Rather, alt-right theology is of a political rather than millenarian variety. This political theology argues not for individual but “collective salvation . . . that is both down-to-earth and fixed on eternity” through the continual renewal, advancement, and rebirth of the white race (Spencer 2015f). Eschewing evangelical concerns with the holy sanctity of life as a sovereign gift, the alt-right understands the value of life and sexual politics along an ethno-nationalist logic, enacting a kind of autoimmunitary politics that seeks to rid the body politic of infectious and dangerous elements within its borders.[5] Crucial to this political project, then, is the protection of national borders and Western values from the erosive forces of cultural Marxism, multiculturalism, and open immigration policy.

Similar to paleoconservatives before him, Spencer sees cultural Marxism, alongside contemporary geo-politics, as a central force behind the erosion of Western civilization, and what those in the alt-right call white genocide. Paradoxically, Spencer also sees an indispensable tool for articulating his metapolitics in the works of Marxist intellectual Antonio Gramsci. Using so-called cultural Marxism against itself, Gramsci’s theories of state power, hegemony, and culture as a driver of political change stand as a useful counterpoint to his and identitarianism. Claiming that the political left has stumbled upon the great truth of the importance of race in contemporary politics, Spencer vehemently argues against social constructionist theories of race and structural racism. However, Spencer’s identitarianism actively rearticulates critical theories of race and appropriates them in the name of the oppression and demise of white peoples.

In this sense we come to perhaps the critical paradox of Spencer’s politics: Marxism, critical cultural theory, and systemic racism are fictions of leftist social justice warriors and academics of color, except when applied to whites. As we saw with the paleoconservatives, when these theories are applied to white folks, they explain how the liberal welfare state, managerial policy elites, and structures of global governance are systematically engaging in the genocide of the white race and western, European culture. Thus, there is a through line between paleoconservatism and the alt-right in their expression of racial reaction as suggested by the work of Omi and Winant (2015); Both paleoconservatives and the alt-right move between recognition and erasure of racial difference depending on their rhetorical situation. Moreover, both rely on traditionalist rhetoric to smooth over the contradictions in their arguments. Race and racism is something that ‘they do;’ white folks do it so as not to fall behind in the multicultural welfare state that is structured to work against white people.

Indeed, in his November 2016 keynote address at the “Become Who We Are” conference, hosted by the NPI, Spencer follows the works of Gottfried and Francis, and argues that a leftist hegemony in US politics is driven ideologically by a politics of anti-white hatred and guilt. These logics are buttressed by the press, entertainment and popular culture, non-governmental organizations, think tanks, and a public policy system that, according to Spencer, amount to a “colonization effort” in which “Western governments go out of their way to seek out the most dysfunctional immigrants possible and relocate them at taxpayer expense” (Spencer 2016e). Any who wish to challenge this hegemonic discourse are punished through censorship and stigmatization, deeming dissidents as racist, politically incorrect, and violent. In Spencer’s metapolitics, the primary enemy, then, stands not as the state apparatus per se, but white folks who have, in his eyes, either failed to recognize or have openly rebuked their biological and cultural supremacy through the internalization of the discourse of white guilt.

As Spencer states in a published version of an April 23, 2015 speech delivered at the 2015 American Renaissance Conference entitled “Why Do They Hate Us?,” “Before we have a Left problem or a Social Justice Warrior problem, or a Black or Jewish problem, we have a white problem. While Guilt is, indeed, so pervasive that it’s difficult to pinpoint, or say where it ends and begins. For millions, who don’t want to think about White Guilt, White Guilt is thinking for them” (Spencer 2015b; emphasis in original). These individuals, commonly referred to as “cucks” in online alt-right forums, stand as the primary obstacle to consciousness raising for an identitarian movement. Rather than embodying the agential, history-making position of white masculinity inherent to the identitarian project, these “cucks” deny their agency and allow the discourse of White Guilt to speak for them, submitting to the forces of the so-called white genocide rather than actively resisting it.

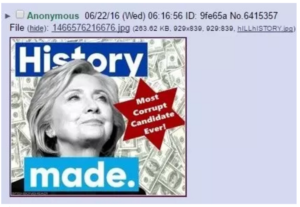

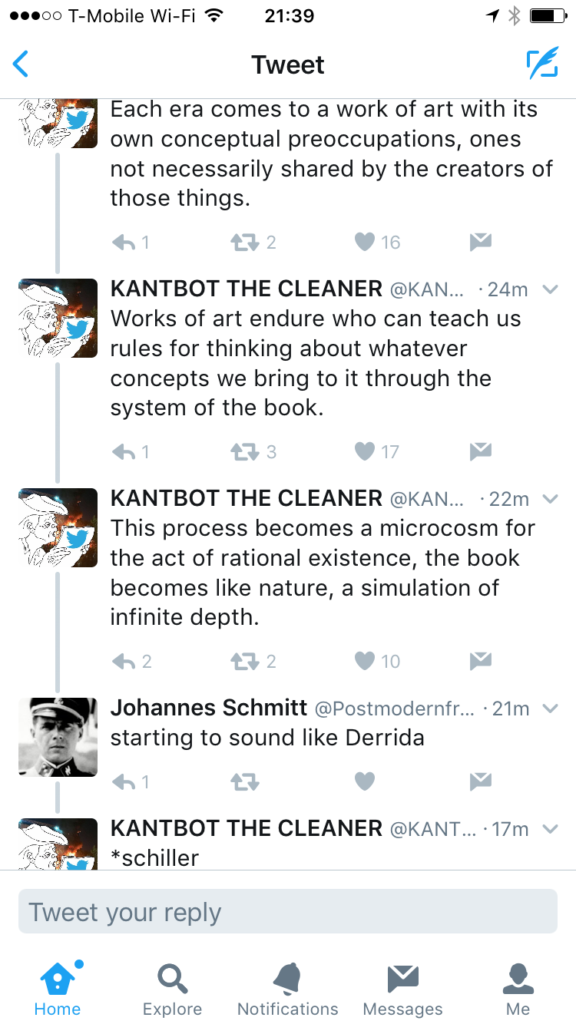

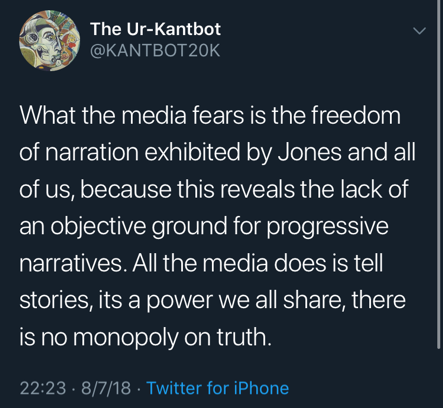

For Spencer, Trump’s rebuke of “the System” represents a first step in overturning the discourse of white guilt and establishing an identitarian movement of Middle Americans. Indeed, Spencer identifies the most powerful component of this system as its “Narrative and Paradigm” that promulgates hatred and oppression of white men through the cultural logic of white guilt (Spencer 2016d). Trump’s rhetoric is figured as capable of toppling the system’s narrative from the inside, using its discourses against itself. Never having “went through the gauntlet, which impresses the ‘right opinions’ upon potential leaders,” Trump is able to buck the system from within (2016d). Transforming oligarchy into populism, spouting vulgar and incendiary hyperbole, and utilizing his celebrity to run a political campaign, represents, for Spencer, the contradictions that have cracked the totalizing structure of the welfare state apparatus and its discursive force. As Spencer argues “Public relations—and postmodern ‘image production’—is, as Baudrillard observed, all about signs without references . . . words without meaning . . . sound and fury signifying nothing . . . bullshit within bullshit. But Trump’s genius is to embed truth within his vulgar and stupid bullshit: deep truths, sometimes hard or harsh truths . . . dangerous truths” (2016d). Calling to Spencer’s famous metaphorical deployment of the film the Matrix—notorious for its play on Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra— and its depiction of Neo as a Platonic Gadfly who climbs out of the cave, seeing the world as it really is after swallowing the red pill, Trump has seen reality and stands as the leader capable of liberating the masses.

The rhetorical force of Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” is representative of this phenomenon for alt-righters. A vacuous soundbyte of postmodern campaign PR, the enthymematic structure of the slogan holds a powerful and harsh truth for followers of the alt-right, one that harkens to the erasure of white European culture and the decline of Western civilization, calling for metapolitical action. The insistence on building a wall on the US-Mexico border, his conciliatory position with Putin and Russia, and his rampant political incorrectness represent the higher idealism of metapolitics—the art of the impossible capable of breaking “the System” and reconfiguring the geopolitical landscape.

Despite his idiocy, self-absorption, vulgarity, and propensity for “bullshit,” then, Trump represents for Spencer an evolutionary step forward, an unleashing of the dynamic power of becoming, “a first stand of European identity politics” (2016d). Styled as an unwitting vehicle for the alt-right, perhaps an evolutionary accident of sorts, Trump is the missing link that pushes conservatism beyond itself. He embodies a Nietzschean will to power and a desire to move beyond political liberalism to a new phase of Western civilization premised on white identity.

The telos of Spencer’s metapolitics, then, is not simply resistance to liberalism but its overthrow in the creation of a white, pan-European ethnostate in North America. This project is not just a return to some glorified past, as it also figures as a necessary step in the continued development and evolution of European peoples. In this sense, the ethnostate imagined by Spencer would be an “Altneuland–an old, new country” (Spencer 2016b). To bring about this state would be to build a territory to protect against the perceived threats of globalism and its attendant cultural logics wherein whites could both “rival the ancients,” and engage in the process of “fostering a new people, who are healthier, stronger, more intelligent, more beautiful, more athletic” (2016b). Advocating for what he calls a peaceful ethnic cleansing, or ethnic redistribution, wherein the powers of the state are utilized to redraw maps according to an ethno-political logic, Spencer strips the politics of diaspora and state power of its violence on peoples of color.