I first met Mandela in 1991 in Johannesburg, at the offices of the ANC during my visit to South Africa, while a guest of the Congress of South African writers, who had invited me to talk at various community centers to share ideas and experiences in the unfolding postapartheid democratic process. Mandela had just resumed the presidency of the ANC after twenty-seven years in prison. I could never have imagined that my very first engagement in the country would be with the legend of that struggle.

Mandela had been part of my literary and political imagination since his days as the Black Pimpernel who, time and again, made a fool of the pursuing apartheid police. A Makerere student at the time, I had just read Orczy’s novel The Scarlet Pimpernel, set during the French Revolution, and it was easy to equate the French reign of terror with apartheid’s and Mandela with the Percy character, the master of disguises and elusive moves. The real Mandela of the Rivonia trial, Robben Island, and worldwide celebrity added to the legend. He had been the subject of poetry, politics, and popular performance. In London, I had worked with the ANC in exile, even met with the hardworking Oliver Tambo, his legal partner, the one that held together a party then dubbed terrorist by the West. So Mandela’s name was always in the horizon of my being, and now, at last, I was going to meet the man.

I did not know what to expect. For some reason, despite the pictures of his sweet self coming out of prison after twenty-seven years, despite, indeed, the current pictures of the man in the world press, I still thought I would see the young lawyer Mandela, hair parted in the middle, slightly puffed cheeks, of long ago, really of his pre-Pimpernel days. I met a lean, dark-suited gentleman, his height dwarfing mine.

Was he going to talk about his prison days, ask me about Kenya politics, or simply voice his dreams for a South Africa whose leadership he would soon assume? He didn’t. He talked mostly about books, what African writers had meant to him and his fellow political prisoners, how books had played a role in buoying up their spirits. Books, yes, books and more books. I felt as if through me he was talking to all writers of the world and history.

We sat at eye level, one on one, but I didn’t realize that he grew on me by the second, a towering presence because he did not try to be towering. Before I knew it, an hour and a half had gone; he was ready to receive the next visitor.

What stayed with me, as I left for KwaZulu Land, was his soft introspective tone. An incident in my first workshop at a library would make me revisit the tone. The itinerary was clear: after the library event a few miles from Durban, we were to drive to the graveyard of Albert Luthuli, the former president of the ANC, to pay respects to his memory. I was in the midst of telling the Kamĩrĩthũ3 story, the community open-air theater that I had been part of, the involvement of workers, small farmers, the landless, the jobless, and the power of an awakened consciousness, when suddenly I saw a commotion in the audience. The ANC chief of security who had accompanied us hurried out of the room, unbuttoning his jacket. They had arrested an Inkatha gunman about to enter the hall. They disarmed him in the nick of time.

My workshop ended abruptly. Our visit to Luthuli’s grave was canceled. All those present, including an American envoy, drove in a convoy back to Durban. It was then that I realized that my driver was an ANC security officer, and he told me that his own brother had been murdered by thugs, allegedly Buthelezi’s men, the week before.

After Durban, it was down to Port Elizabeth, in the Eastern Cape. I visited the humble home of one of the ANC cadres. He was a father who seemed to embrace the warmth of his family in gratitude, as if it had been a gift he had not expected. Then later, he took me to the back of the house. He did not show it to me, but he pointed to where his AK-47 was hidden. I think he saw himself as a soldier on leave, or enjoying a temporary cease-fire with the enemy. He could be called to arms at any time, and he could never, of course, be sure of a safe return to his family.

The two incidents brought home to me the meaning of Mandela’s introspective tone. The country was literally on the verge of a bloodbath, and he knew it. He held the key to its stability; despite his calm demeanor, this must have weighed on him.

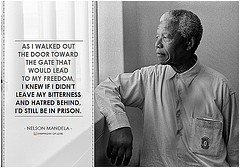

But Mandela held the nation together, the four years that he was president, guided by the realization that there is no room for vengeance in good politics. It was easier to tear down than to build. Even in serving one term, he showed his faith in the ANC and the people.

I would meet Mandela again after my 2003 Steve Biko Memorial Lecture. The meeting was in Johannesburg again, this time in the offices of his foundation. By then he had left office, the first black president of a Free South Africa, and Thabo Mbeki had taken over as the second. He was different this time, a bit more effusive. He talked about the contribution of Cuba and African states to the struggle. He talked a little about his continuing contact with leaders of the world, Bush and Blair in particular. He reminisced over Biko, paying tribute to the role of the black consciousness movement and indeed that of the other political parties in the liberation, mentioning Robert Sobukwe by name. Again, so generous in his inclusiveness. The question of his giving the Steve Biko lecture came up, and indeed he gave one, the following year.

As we were leaving, he stood up and placed his hand on my shoulder. Thus we walked to the door, he leaning on my shoulder. I told Xolela Mangcu, my host, how touching that was: he walking us to the door, his hand on my shoulder, a gesture almost reminiscent of the image of his long walk to freedom. Xolela laughed. Sorry, nothing personal; he does that with people. For support. Yes, he was clearly more frail than the first time we met, but his spirits were still up, once again his charisma and his towering presence commanding awe and respect rather than demanding it.

The third time we met was in 2004, when he, Ali Mazrui, and I were to be accorded honorary doctorates to mark the renaming and relaunching of the former University of Transkei as Walter Sisulu University. Walter Sisulu, an ANC stalwart, was also Mandela’s political and spiritual mentor. My wife, Njeeri, and our two children, Mumbi and Thiong’o, were less excited about my doctorate than the fact that they were going to meet Mandela. It was an emotional moment for me because I was returning to Kenya for the first time after twenty-two years of forced exile.

Alas, we never met up with him: he was down with something, he could not make it to the ceremony, and he would be given his robes at his home. But a few days later, we had the pleasure of visiting his birthplace, Qunu, where now he will rest forever.

His passing on, though expected, shocked me: at the back of my mind was always a hope that the man who had cheated death many times would once more rebound. He remains a towering figure in African and world politics.

When Mandela was released from prison, captured in the iconic picture of his walking hand in hand with Winnie Mandela, I wrote an article in Gĩkũyũ, “Kũngũ Baba Mandela” (Welcome home Father Mandela), because I could not see myself recording this moment in any but an African language. I compared him to mythic figures, Prometheus in particular. For like Prometheus, he had been chained to a rock for bringing to humans the knowledge of fire, really, the secrets to energy and light. He had survived, and now, at ninety-five, he had passed to join other heroes and heroines of history and myth.

Blessed Peace, Mandela

translated from the Gĩkũ yũ

Even those that then called him a terrorist

Now acclaim him a freedom fighter

Those that once wanted him gone

Are now shedding tears that he’s gone

It is said that truth never dies

It cannot be buried in a hole

They tried to kill it with bullets

They wondered how did it escape?

They put it in chains

They sent it to Rob’em Island

They made it break stones twenty-seven years

They tortured it to make truth give up hope

They tried all to make truth surrender to lies

They did not realize it was the body breaking stones

That truth cut thru the handcuffs and barbed wires long ago

That it was truth that guided the armed struggle

Singing that which had been sung by other seekers of freedom

You can send us to exile and prisons

Or confine us to islands

But we shall never stop struggling for freedom . . .

Mandela Madiba Rolihlahla of Thembu and African clan

Your body that has gone to rest under the shades of holy peace

The truth they tried to shoot down with bullets

The truth they put in hand and leg chains

The truth for which they put you in jail and detention

That truth lives on among the people forever

In the hearts of all fighters for truth and justice the world over

___

2. Parts of this article have been published in the Standard (Kenya); and the Sunday Independent (South Africa).

3. For more on Kamĩrĩthũ, see my books, Decolonizing the Mind and Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary.

___

–Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o