This article has been peer-reviewed by the b2o editorial board.

“Je suis oiseau, voyez mes ailes. Vive la gent qui fend les air!

… Je suis souris: vivent les rats!”[1]

A pigeon in a mural. In early August 2011, the American street artist Shepard Fairey paints a mural in Copenhagen, Denmark, on a wall adjacent to the “ground zero” of a recently demolished squat called Ungdomshuset (the Youth House). Fairey could hardly have chosen a worse spot in the city to sport his ready-made design of a pigeon hovering over the word “peace”: shortly after the mural’s completion, graffiti writers defaced what Fairey refers to as “my Peace Dove mural.”[2] Their message was clear: “no peace” and “go home yankee hipster.” To make matters worse, Fairey ended his trip to Copenhagen with a “black eye and a bruised rib” after a violent assault.[3]

Today, Fairey’s pigeon—a take on Picasso’s famous peace dove—is still aloft in the mural high above the vacant lot, a serene emblem of triumphant peace. Unlike Hito Steyerl’s parable of contemporary art in “A Tank on a Pedestal”—where she recounts how pro-Russian separatists drove a Soviet battle tank “off a World War II memorial pedestal” to use it in guerilla warfare—the pigeon was never hijacked from its mural and redeployed as a war machine.[4] Or was it? Considering Fairey’s controversial mural from the combined perspective of art history, the history of counterinsurgency, and late-modern warfare prompts a series of questions that pertain to our “hypercontemporary” moment in much the same way that Steyerl’s example of a tank on a pedestal does: is the mural a theater of war? Picasso’s peace dove, a drone?

In this essay, I consider Fairey’s pigeon in a mural as an art-historical index for the “bodies of beliefs, images, values and techniques of representation” that characterize the “historical situation” of US drone warfare under the Obama administration.[5] By analyzing the peace-dove motif, and situating it in the broader context of drone warfare, I argue that the pigeon-cum-peace-dove emerges as an instrument of war alongside its mechanical double, the drone. The pigeon in the mural, then, is more than some helpless animal caught in the crossfire of a chance conflict: it is also a cipher for late capitalist war.

In what follows, I begin from the controversy surrounding Fairey’s Copenhagen peace dove mural before zooming out to reconsider how the peace dove motif relates to the conduct of war and politics from the end of the Second World War to the age of drone warfare—and beyond. As I show, the peace dove motif is historically at the center of an “image war” in which opposing political ideologies struggle for mastery in the realm of representations.[6] The story of the peace dove from Picasso through to Fairey, in other words, is the story of how an “icon of the left” was detached from its origins and aligned with a triumphant conception of liberal peace: one that effectively helped obscure US military aggression in the era of drone warfare.[7] Ultimately, then, the image conflict traced and contextualized in this essay points toward the historical limits of what the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in a seminal essay from 1795, called the “sweet dream of perpetual peace.”[8]

I

“You don’t have to be Picasso, you just need to be inspired by Barack Obama.”[9]

To the Copenhagen Youth House activists, Fairey’s artistic peace statement was unwanted because it literally and symbolically erased the traces of conflict from the site of a year-long struggle that revolved around systemic dynamics of capitalist gentrification, political repression, and police violence. But the activists’ fury—as the tag line “go home yankee hipster” suggests—was equally fueled by their perception that Fairey’s peace message converged with President Obama’s rhetoric in the US-led war on terror by other supposedly more “peaceful” means, mostly drones.

On the street address Jagtvej 69 in Copenhagen where the Youth House once stood, there is now an empty, graffiti-covered lot. The house that once stood there, by contrast, was a vibrant hub for radical politics and dissidence for more than a century. Historical figures like Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin would pass through to give political speeches and conspire with local revolutionaries and exiled comrades. It was also here, in August 1910, that the German Marxist Clara Zetkin proposed the annual celebration of what is now known as the International Women’s Day.

After the eclipse of the historical workers’ movement, the building was temporarily abandoned. In 1982, in the wake of severe street confrontations, the Copenhagen municipality surrendered the disused building to the “BZ-movement” of young squatters, dropouts, and punks.[10] People started referring to the building as Ungdomshuset (the Youth House), which became a crucial countercultural node for the European punk movement and radicals of various stripes.

Around the turn of the millennium, the Copenhagen municipality sold off the estate to a Christian sect. The sale technically turned the building into an illegal “squat,” as its users refused to acknowledge the change of ownership. Instead, existing tensions rose, and conflicts about “the right to the city” developed into riots. The militants responded to eviction notices and a sensation-hungry press by hanging a banner from the windows of the occupied building, reading: “For sale, including 500 autonomist stone-throwing violent psychopaths from hell.”[11]

Early one morning in March 2007, one of the most carefully planned and most spectacular police operations ever carried out in Denmark took place. In scenes resembling a film, police helicopters lowered a team of special operations agents onto the Youth House, broke through barricaded windows with power tools, and filled the house with tear gas to evict the militants and clear the house for demolition. As news of the eviction spread, Copenhagen’s streets became ablaze with anger. Hundreds of militants from all over Europe joined the struggle. In their effort to “keep the peace,” while facing some of the most severe riots Denmark had ever seen, the Copenhagen police department mustered reinforcements from neighboring districts, and even neighboring countries.[12]

The state forces far outnumbered protesters and rioters, who could not prevent the Youth House’s eventual demolition.[13] Still, the riots, protests, and demonstrations carried on relentlessly after the demolition, and every single Thursday for several years, thousands of protesters would ritually march through the city. Even though in 2008 the municipality yielded to the pressure and allotted another building in the city’s outskirts to activist purposes, the Thursday protests carried on unrelentingly for several years. The original battle cry—nothing forgotten, nothing forgiven—still resounded among a discontented youth when Shepard Fairey made his cameo appearance in 2011.

When Fairey flew in to decorate the city—Fairey’s stint as a Copenhagen street artist included an art show at the self-styled “street art gallery,” V1, and no fewer than seven murals in prime locations across the city—the Youth House struggles were still recent memory. In a blog post, Fairey recalls being aware that “the mural location in question had a controversial history” but says he thought to himself: “what a shame, I hope I can do something that is a symbolically positive transformation.”[14] Apparently, some activists thought differently. Even before the mural was completed it was destroyed by graffiti.

The destruction of the Copenhagen mural and the ensuing image conflict soon attracted international media attention. The Guardian, for instance, reported that Fairey’s mural “appeared to reopen old wounds, with critics accusing Fairey of peddling government-funded propaganda.”[15] Fairey, in turn, insisted that his mural was non-political, stressing that he was merely promoting a universal message of peace, and went back to restore his mural. Just as quickly as he restored it, however, someone destroyed it anew.

V1, Fairey’s local art gallery, stepped in to mediate by inviting some artists, who supposedly represented the Youth House, to repaint the bottom half of the mural in a design of their own choice. Fairey recalls:

It was a powerful scene of hostile riot police like those who had evicted the Youth House dwellers and it incorporated one of the paint bombs on the mural as if it had been thrown by a riot cop. I thought it was a brilliant solution reflecting the history of the site and keeping my pro-peace message intact, but adding additional emphasis to the idea that peace is always facing attack from injustice that I felt was already more subtly implied by placing the dove in a target.[16]

These changes did little to help, and the mural kept getting attacked. And so too, unfortunately, did the artist. Soon, a mock version of the famous Obama posters the artist created for the 2008 US presidential election appeared on Copenhagen street corners. Instead of a picture of Obama, the poster now featured Fairey, with a bruised eye, over the familiar caption: HOPE. But why such vehement opposition? And “how”—as the artist asked—“is a mural advocating global peace inflammatory”?[17]

To understand the antagonism toward Fairey, one needs to consider how Fairey glossed over decades of struggles between local activists and a repressive state apparatus parading as the apotheosis of liberal democracy. As the mock poster amply suggests, the activists’ perception of Fairey as a useful idiot for American cultural imperialism originates in the street artist’s world-renown campaign to help elect Obama for president.

In 2008, Fairey created and distributed thousands of stickers, posters, T-shirts, and other merchandise to support the future president. Fairey even painted an “Obama mural” in Hollywood, photographed from a spectacular bird’s eye view. Across these images, the graphic form of Obama’s face is invariant. Fairey’s instantly recognizable aesthetic, which borrows in equal parts from political propaganda, pop art, and advertising, led The New Yorker’s art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, to extol Fairey’s Obama HOPE poster as “the most efficacious American political illustration since ‘Uncle Sam Wants You.’”[18]

Obama too, recognized the poster’s political efficacy. In a letter of appreciation to the street artist, Obama said: “I would like to thank you for using your talent in support of my campaign. […] Your images have a profound effect on people, whether seen in a gallery or on a stop sign. I am privileged to be a part of your artwork and proud to have your support.”[19] Soon after, with a little help from his “poster boy,” as the media later dubbed Fairey, Obama was elected. He was sworn into office on January 20, 2009. The rest is history. A history of hope, among other things.

Looking back from the recent Trump era, Obama’s presidency might appear to embody the progressive march towards what Kant, in 1795, had called “perpetual peace.” But the “sweet dream of perpetual peace,” as Kant stressed—to shield himself from allegations of subversive intent—remains precisely that: a philosopher’s dream, to which the “worldly statesman” does not need to “pay […] any heed.”[20] And though the worldly statesman Obama rhetorically advocated peace, he didn’t shy back from using military force.

One of President Obama’s first military campaigns, what became known as the “Obama-surge,” consisted in ramping up US troops in Afghanistan by an additional 17.000 soldiers. Later Obama’s military strategy shifted toward a series of so-called “small wars” or military interventions in Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan, among other places, that most certainly violated key philosophical articles in Kant’s treatise on peace – e.g. intervening forcibly in another state and employing “assassins.”[21] Advanced weapon technologies or “drones” for carrying out assassinations were instrumental to what some would describe as the Obama administration’s transformation of “the whole concept of war,” along with its attendant relationship to peace.[22]

However, Obama was not yet another “war president” but rather an example of a statesman who carefully paid heed to the dream of lasting peace and whose chief political task, accordingly, was to engineer this peace by all means necessary. One of the most potent tools that Obama inherited and redefined was the infamous US drone program. However, while new technology may have changed the reality of warfare, it takes more than technical advances to change social conceptions of war. Critics have rightly exposed the ambiguities in Obama’s peace rhetoric.[23] But which other “instruments” may have helped transform our understanding of war and its relationship to peace?

Key here, I believe, is how state and non-state actors ideologically supercharge artworks to wage “image war.”[24] One of the most famous examples of image war occurred when US officials, prior to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, deemed the reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica that was hanging in the UN Security Council chamber an inappropriate backdrop and ordered it to be concealed behind a curtain before the media arrived. According to the Retort collective’s analysis, this incident illustrates how states “struggle for mastery in the realm of the image.”[25] Can we pursue this analysis one step further to explore forms of image war that do not directly involve the state’s micromanagement of the “means of symbolic production”?

The advent of blogs, social media, and algorithms has challenged traditional top-down approaches to the politics of representation. As the Situationist Guy Debord pointed out at the dawn of our networked era, new decentralized or “diffuse” forms of control in the realm of the image exist side by side with more “concentrated” forms of spectacular representation.[26] State power no longer relies to the same extent on micromanaging appearances. Instead, as in the case of the Obama administration’s quasi-official endorsement of Fairey’s artwork, state power now benefits equally from artists-as-influencers who more or less wittingly align their aesthetics with the ideological exigencies of those in power.

Fairey placing his pigeon in a target to “subtly” imply, in his own words, “that peace is always facing attack from injustice” is an example of how ideology exists, independently of overt state control, in the expanded realm of art.[27] Fairey’s idea of a fragile and easily victimized peace—as not-so-subtly underscored by the white-feathered creature placed in a target—thus readily exposes a key ideological component of the liberal reasoning behind late-modern warfare: that perpetual peace requires an advanced pre-emptive “security” regime to ward off potential attacks from the enemies of peace.

In the liberal conception of peace, “keeping the peace” does not mean waging war indiscriminately but protecting the international community’s fragile state of equilibrium from external threats. What the US-led international community refers to as “peace” is not just a misnomer for perpetual war but also, in a historically specific sense, the precondition for newfangled forms of pre-emptive state violence, the urbanization of drone warfare, and the policing of racialized “surplus populations.”[28] From war power to police power, in other words.[29]

From such a perspective, Fairey’s pigeon dovetails with what Mark Neocleous calls the “liberal peace thesis.”[30] Now “a standard trope in the political discourse of international theory,” Neocleous argues, the liberal peace thesis is an untenable “claim for capitalism’s essentially pacific grounds.”[31] Since its inception in eighteenth-century political philosophy, the proponents of the liberal peace thesis have ignored evidence that contradicts the idea that free markets are an effective antidote to armed conflict. The constitutive violence at the heart of the liberal peace thesis, Neocleous notes, is encapsulated in ahistorical interpretations of Kant’s essay:

Liberalism, and thus many international lawyers, like [sic] to cite Kant’s essay ‘Perpetual Peace’ as a key philosophical document outlining the liberal foundations of peace, yet usually omit the fact that the essay was published in October 1795, just one month after the military suppression of the revolt in Poland led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Poland’s partition by Russia and Prussia, and about which Kant had nothing to say.[32]

Likewise, proponents of the liberal peace thesis in the age of drone warfare typically have little to say about the lethal violence undergirding the “peace” discourse of the Global North. Obama is, again, a case in point. As one of the most popular American presidents ever, Obama was—and to some extent still is—primarily perceived as the embodiment of liberal democracy. In terms of US politics, Obama is something close to the incarnation of the liberal peace thesis: a champion of the most politically progressive values, with “peace” chief among them.

Eleven months into his presidency, in December 2009, Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for helping the US to play a more constructive role in world politics and for preferring “dialogue and negotiations” as “instruments for resolving even the most difficult international conflicts.”[33] The news that the 44th American president had received the world’s most prestigious peace prize resonated globally. Prefiguring Fairey’s pigeon mural, the Spanish newspaper El Pais published a cartoon picturing Obama as a “black peace dove.”[34]

But the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize laureate admitted to having “instruments” other than just “dialogue and negotiations” in his peace arsenal. In his acceptance speech, Obama acknowledged that, as “the Commander-in-Chief of the military of a nation in the midst of two wars,” he was “filled with difficult questions about the relationship between war and peace.”[35] The answer to these “difficult questions,” as is now well known, took the form of the drone.

As Daniel Klaidman stated in his contemporaneous bestselling book Kill or Capture: the War on Terror and the Soul of the Obama Presidency, “[b]y the time Obama accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2009, he had authorized more drone strikes than George W. Bush had approved during his entire presidency.”[36] According to estimates produced by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Obama oversaw “ten times more” air strikes than his predecessor, amounting to “a total of 563 strikes, largely by drones,” in Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen among other places. The corresponding death-by-drone casualties logged by the bureau amount to somewhere “between 384 and 807 civilians,” and counting.[37]

In his Nobel Peace Prize remarks, Obama gauged the “costs of armed conflict” in relation to the “imperatives of a just peace” and concluded: “So yes, the instruments of war do have a role to play in preserving the peace.”[38] Obama’s closing remark?

Clear-eyed, we can understand that there will be war, and still strive for peace. We can do that—for that is the story of human progress; that’s the hope of all the world; and at this moment of challenge, that must be our work here on Earth.[39]

Leaving aside the question of whether the US-led, drone-based peace campaign is the story of human progress, it is clear that Obama’s work on Earth changed how we think about war and international conflict. Touting promises of “hope,” “progress,” and “change” (incidentally, the words that Fairey interchangeably used on his iconic HOPE posters), the Obama administration helped transform the concept of warfare into a logic of global “security.” As Grégoire Chamayou, in his instant classic of the drone age, pointed out, “in the logic of this security, based on the preventive elimination of dangerous individuals, ‘warfare’ takes the form of vast campaigns of extrajudiciary executions.”[40] As Chamayou remarks, “the names given to the drones—Predators (birds of prey) and Reapers (angels of death)—are certainly well chosen.”[41] So, is the pigeon in Fairey’s mural a bird of prey? The peace dove, an angel of death? Let’s examine in more detail the history of this magically ambiguous motif.

II

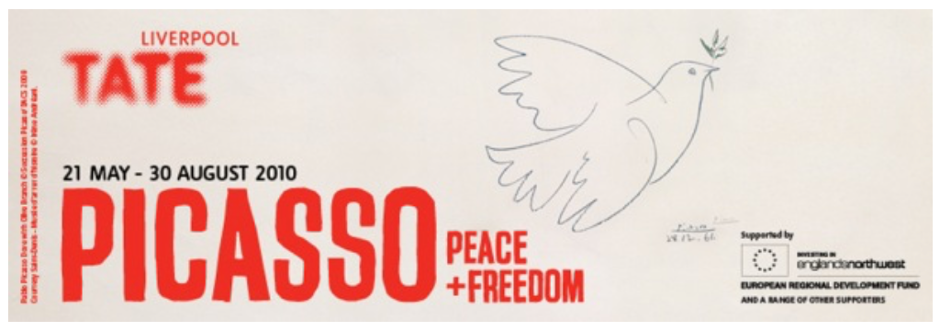

In 2010, the year before Fairey painted his “Peace Dove mural” in Copenhagen, there had been a global celebration of Picasso’s work. The temporary closure of the Picasso Museum in Paris, which sent many of Picasso’s works on tours of the global museum circuit, enabled major Picasso retrospectives in Moscow, New York, Münster, Seattle, Zürich, Vienna, and Liverpool.[42] The Liverpool exhibition, which took place at the Tate Liverpool gallery, was called Picasso: Peace and Freedom.

The exhibition frontispiece sported one of the artist’s iconic peace dove designs. According to the exhibition statement, this would be the first exhibition “to examine in depth the artist’s engagement with politics and the Peace Movement,” and it would “reflect a new Picasso for a new time.”[43] A new Picasso for a new time—but what “new time,” exactly? A time before Brexit, Boris Johnson, and Trump. A time of “hope,” for sure. A time that embodied all the most progressive values and hopes of Western liberal democracies. But how did Picasso’s peace dove become an emblem for an overarching liberal narrative of progress, peace and freedom?

While the dove has been a symbol of peace since ancient times, it was in the hands of the twentieth century’s most famous artist, Pablo Picasso, that it acquired its status as the quasi-official symbol of world peace. Appropriately to our story, Picasso’s peace dove originated, it is not often noted, as a fusion of street art avant la lettre and political propaganda. According to art historian Sarah Wilson, Picasso’s peace dove first appeared on the world stage in a poster on the streets of Paris announcing the World Congress for Peace, Paris-Prague, in 1949. It was the French communist and founding member of Surrealism, Louis Aragon, who, during a visit to Picasso’s studio, had chosen “Picasso’s pigeon—a soft wash drawing on a black ground” as a symbol for the upcoming international peace congress.[44]

Thanks to mechanical reproduction techniques, Picasso’s pigeon or La Colombe (1949)—originally intended as a limited edition lithograph of 50 prints—was being churned out by the thousands. Under the French Communist Party (PCF) auspices, Picasso’s delicate peace dove motif thus evolved into what specialist in political imagery Zvonimir Novak fittingly describes as a machine de guerre graphique, a graphical war machine.[45]

In response to the PCF’s “extremely successful billboard campaign,” French anti-communists, covertly sponsored by the CIA, formed a movement called Paix et Liberté (peace and freedom), with the sole purpose of discrediting the communist peace campaign that symbolically centered on Picasso’s wildly popular peace dove motif.[46] Did the 2010 Tate exhibition, Picasso: Peace and Freedom, perhaps intend some historical pun by alluding to the anti-communist propaganda of Paix et liberté in their exhibition title? It is difficult to tell, especially given that there was also a pacifist communist group with that name in the interwar years.[47] The changing ideological valence of the terms “peace and freedom” notwithstanding, the recuperation of Picasso’s peace dove exemplifies how art and politics intertwine in ways that exceed artistic intent. Much like Picasso’s Guernica was detached from its historical origins in “exchange for its continuing topicality”—as O.K. Werckmeister argued in his seminal book Icons of the Left—so too did his peace dove evolve into an all-purpose image of a politically non-descript peace. [48]

The original Paix et liberté group is an essential component in the history of Picasso’s peace dove. It was the French socialist politician, Jean-Paul David, who in 1950 founded Paix et liberté together with fellow partisans of the North Atlantic Treaty. To their concern, the signing of the treaty had been “effectively eclipsed” in France by the press coverage of the first communist peace congress.[49] The group’s aesthetic counter-offensive launched a flood of “posters supplemented by newsletters, brochures, pamphlets, stickers, and tracts that used the words, themes and symbols of the Communist Party to counter their message.”[50] In the climate of tense ideological antagonism that characterized the early phases of the Cold War, Novak recalls, the Parisian “walls were a site for a permanent war between billposters, the streets a battlefield scattered with paper tracts.”[51] A recurrent feature of the anti-communist campaign was how it exploited a deep-seated cultural sense of ambiguity about birds to draw attention to the two-faced nature of the communist peace symbol.

In a popular fable by Jean de La Fontaine, “The Bat and The Weasels,” a bat is caught by a weasel with an appetite for mice. The poor creature cunningly escapes death by convincing the predator that it is “not of that species” at all: “I, a mouse? No, no, some people must have told you merely out of malice. Thanks to the creator of the universe, I am a bird: behold my wings. Long live the nation that skims the air.” A little later, the same bat is caught again by another weasel, this time one that harbors an “enmity” toward birds. Again, the clever bat escapes. But this time by refusing to be a bird, insisting that, surely, it is the feathers that make the bird, not the mere ability to fly. La Fontaine’s fable—which, as one can imagine, also lent itself to French anti-Semitic political caricatures—was used against the communists to present them as morally suspect.

Because much of the support for the PCF in the 1940s and 1950s stemmed from the glory of the communist resistance movement’s fight against fascism during the Second World War, the Fontainesque anti-communist propaganda centered on undermining the idea that communists could be French republican patriots. One particular tract, a precursor to the Paix et liberté variations that followed in its path, gets this message across: recto, there is a winged creature draped in the French colors, with a caption that reads “I am bird, behold my wings”; verso, the creature reveals its true colors, a deep communist red, hammer and sickle on its chest, with the caption now reading “I am a mouse! Long live the rats!”

Perhaps the most successful attack of this kind was the poster, La colombe qui fait boum, which ingeniously transformed Picasso’s peace dove into an explosive device. According to Wilson, “the explosive slogan was soon pasted all over the walls of Paris as Picasso’s Dove had been: the print run was purportedly 300,000.”[52] As Wilson notes, Picasso’s voluminous FBI file references the satirical poster along with a press clipping from The Washington Post, February 17, 1952:

The back, the pouting breast and the belly made the form of a tank: the tail feathers were exhaust fumes. The head was a turret and the beak a cannon, the hammer and sickle brand was on the shoulder. There was a simple five word caption: ‘The Dove that goes Boom’. All Paris laughed and the Communists were ridiculed.[53]

The satirical attacks may have harmed the PCF’s image momentarily, but Picasso’s peace dove took off to become the quasi-official mascot of the world peace movement. From today’s perspective, however, the peace dove of the Picasso: Peace and Freedom exhibition at Tate Liverpool Gallery stands, along with Fairey’s peace dove mural, at the end of the historical arc of triumphant liberalism.

Retrospectively, 1989 was a hinge moment. On this crucial threshold from the “modern” to the “contemporary,” Francis Fukuyama famously trumpeted the “end of history” based on the alleged “fact that ‘peace’ seems to be breaking out in many regions of the world.”[54] In the prominent political scientist’s global peace narrative, “Western liberal democracy” had revealed itself to be the “endpoint of mankind’s ideological evolution.”[55] The future, from this perspective, was canceled. The only significant task left to humankind would be to come to terms with the past, a perpetual historical curating. Or, in Fukuyama’s own words: “In the post-historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history.”[56] But the “modern” constraints and contradictions of the pigeon-cum-peace-dove were carried over into the age of drone warfare and continues to shape our hypercontemporary—and oddly Fontainesque—condition.

III

Imagine this. Just as Shepard Fairey puts the finishing touches to his mural in Copenhagen, a mysterious mechanical bird crashes to the ground. But Fairey, in deep concentration, perhaps mulling over whether to include an olive branch in the pigeon’s beak, doesn’t notice it at all. The street artist is so immersed in his work that he forgets where he is. Los Angeles, New York, Reykjavik, or perhaps Tel Aviv? When Fairey looks around to see what the commotion is about, it is nightfall in Balochistan Province, Pakistan. A man, lit up by the headlights of a parked car, holds up what “looks a bit like a silver bird,” while another man stands guard with a Kalashnikov.[57] What’s going on here? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? A toy? No, it’s “a small combat-proven spy drone.”[58]

Of course, Fairey painting his peace dove mural and the “weird, birdlike mystery drone” falling from the sky were two separate events that happened in two different places. Fairey wasn’t magically beamed into Pakistan. Sheer historical coincidence brings these two birds to the fore at this exact historical moment (August 2011). But there is something uncanny about these twin events that brings to mind the work of the Egyptian artist Heba Y. Amin, who in As Birds Flying (video, 2016) and The General’s Stork (mixed media, 2016–ongoing), mines the contemporary drone imaginary through an aesthetic exploration of the historical and ideological overlaps between birds and drones.

Amin does not discuss Shepard Fairey’s peace dove, but she does refer to the Pakistan “mystery drone” as an example of how drones are nested in deep-seated cultural imaginaries about birds flying. In The Generals Stork, Amin relates the crashed mystery drone to its commercial twin, the then much-hyped “SmartBird” by Festo engineering, and brings these two birds-as-drones into a larger media narrative about how, in 2013, Egyptian authorities detained a migratory stork on suspicions of espionage because it was equipped with an electronic tracking device. A device that, as it transpired, merely registered the bird’s migratory patterns.

To Amin, the Pakistan spy-drone crash highlights the progressive obscuring of the boundaries between natural beings and military artifacts that characterize situations of drone warfare and creates the conditions of possibility not only for storks being detained but also for generalizing a sense of paranoia that pervades everyday life under drone surveillance: “Imagine the confusion of finding such an object in a place where people are so accustomed to drone attacks. What happens when we can no longer differentiate a machine from a living thing?”[59]

Amin critically addresses the projected drone future where birds-as-drones and other similar creatures “naturally” circle the sky above. And Festo’s “smart bird,” to be sure, marks a historical threshold. The “SmartbBird” has since inspired a flock of cheaply available “bionic” or “bio-mimetic” drones, so called because they are engineered to mimic birds and other living creatures. In 2016, for instance, Amazon patented new drone technology that would allow future delivery drones to perch “like pigeons” on streetlights, church steeples, and other vertical urban structures.[60] When the world’s largest online retailer jumps on the bionic drone bandwagon, we can start to imagine what the drone future might bring.

Indeed, if one is to believe the media hype, bio-inspired drones might be the next big thing. One 2019 NBC news report rubric reads: “Inspired by the aerial abilities of birds, bats and insects, researchers are crafting a new generation of ultralight drones that lack propellers and are equipped not with fixed wings but with flapping ones.”[61] More recent examples confirming this trend are legion. In contemporary robotics, common pigeons of the kind that inspired Picasso’s peace dove motif are being anatomically dissected to teach semi-autonomous machines to perform more like their feathered brethren.[62] The common pigeon that inspired Picasso’s peace dove is, essentially, a proto-drone.[63]

Amin’s art project, As Birds Flying, further instructs us about the historical and symbolic crossovers between birds and their mechanical counterparts, the drones, and crucially brings colonialism into the frame. Amin’s film is based on found drone footage of locations in the Middle East, including views of Israeli settlements, and poetically reinterprets how religious myths, colonial wars, airpower, spy birds, surveillance technologies, and late-modern drone warfare historically interlock.

In the artistic research project The General’s Stork, Amin recalls the story of Lord Allenby’s seizure of Jerusalem from the Ottoman Turks in 1917 to show how deep the bird-as-drone imaginary reaches into the historical texture of orientalism and colonialism:

[Lord Allenby] launched an attack based on a biblical prophecy found in the book of Isaiah 31:5, which states: “As birds flying, so will the Lord of hosts defend Jerusalem; defending also he will deliver it; and passing over he will preserve it.” By reason of this prophecy, he sent as many planes as possible to fly over Jerusalem, forcing the Turks to surrender the city. So, when Allenby marched into Jerusalem, it was seen as a prophecy fulfilled. Right at the core of this prophetic figure, or augury, is the symbolic and actual presence of the avian, the prophecy of the birds flying over Jerusalem, the birds mutating into airplanes, the airplanes mutating into drones, and the menace of predictive drone technology metastasizing into the specter of aerial bombardment. This prophecy has become predictive in terms of drone technology, envisioning what will be and what is yet to come.[64]

Amin’s examination of “the symbolic and actual presence of the avian” in the historical ascendance of the drone underscores how the realms of the symbolic and the real overlap. Just as the biblical prophecy helped Lord Allenby visualize and ultimately legitimize Jerusalem’s destruction, the liberal peace thesis provides ideological justification for the US-led drone program. Lord Allenby’s prophecy materialized as mechanical birds flying over Jerusalem dropping bombs while Picasso’s peace dove, in turn, participates in an ongoing image war with no less deadly consequences. As diverse as these different historical contexts of killing may be, they are equally grounded in deep-seated cultural narratives with a near palpable orientalist subtext.

Seen from an art-historical perspective, the migration of the common pigeon (Colombia livia)—from Picasso’s 1949 ink-wash drawing through to Fairey’s 2011 peace dove mural and further still—forms an irregular pattern across history that culminates symbolically at the height of the age of drone warfare and resonates into our present moment. Today, there is a more-than-symbolic sense in which Picasso’s peace dove mutates into a drone—or a swarm of drones, to be exact.

In December 2016, as Obama’s presidency was coming to an end, the skies above the Disney World theme park “dazzled with drones” in a spectacular night-time show: “For Starbright Holidays’ finale, the drones form a dove. With the music swelling, the sequence packs an emotional punch.”[65] In an article in USA Today, Ayala, one of Disney’s so-called Imagineers (that is, an imagination engineer) notes that “his team originally animated the word, ‘peace,’ but later removed it. The dove, the Imagineers figured, transcends language and culture. ‘We have the symbol of peace,’ notes Ayala. ‘What better way to show it than from the stars themselves—from the universe?’”[66]

Although arbitrary to the events recounted in this essay, the Disney show appears as a grand finale of the ideology of liberal peace as epitomized by the drone. It also bespeaks what Andrea Miller calls the “specter of the drone,” an example of how “diffuse histories and geographies of war are folded into the sign of the drone” in new forms of entertainment.[67] The proliferation of drones as a tool of entertainment since 2016 practically refutes its reputation as an aggressive instrument of US neo-imperialist war in ways that are most certainly conducive to the drone industry. President-elect Joe Biden’s drone fireworks celebration in November 2020 testifies to this historical shift—and raises important questions about what the drone future might hold.[68] So where are we now? And what happened to the pigeon in the mural?

*

In 2013, Shepard Fairey fell out of love with his former political icon, Obama, and became an outspoken critic of drone warfare (if not of liberal peace).[69] As Fairey’s criticism of Obama’s use of drones became known to the public, one blogger quipped: “End of a Fairey Tale: Poster Artist Says Obama’s Drones Killed ‘Hope’.”[70] A 2015 Washington Post op-ed took a similar line: “Obama’s done. It’s the perfect metaphor for the Obama administration for Republicans. That widespread enthusiasm for Obama in 2008 has eroded, and with less than two years left in office, one of his most visible supporters, the guy who made the most iconic image of the Obama years has even turned on him.”[71] The commentator turned out to be correct: Obama was done. The Fairey Tale of perpetual peace ended, as we now know, with the brutal awakening in 2017 to the Trump era and the spectacular rise of late-capitalist fascism.[72]

The story about the destruction of Fairey’s peace dove mural in Copenhagen now belongs in a backroom of Fukuyama’s “museum of human history.” And no one paid much attention to Shepard Fairey’s peace dove after its attempted assassination by graffiti writers in 2011. After Fairey returned to the US, the partly destroyed mural was left to its own devices; an aesthetic prop in the staging of a “radical chic” image that accompanies Copenhagen’s ongoing gentrification. To this day, Fairey’s pigeon remains intact in its mural, hovering peacefully above street level commotion. Its mechanical double, however, is as busy as a bee.

The Covid 19-pandemic has rekindled interest in “bionic” drones inspired by flying creatures such as birds, bats, and bees. In China, for instance, drones disguised as white doves surveil the population, firing up the imagination of conspiracy theorists worldwide.[73] In the US and in many other countries, a new breed of Fontainesque drones with and without feathers are operating daily outside of the military context. In addition to commercial drones and drones operated by amateur hobbyists, so-called “pandemic drones” are now performing various roles: delivering medical supplies, sanitizing streets, or “shouting” at people to keep their distance.

According to statistics from the Bard College Drone Center, more than 500 public safety agencies acquired drones between 2018 and 2020, bringing their total number close to 1,600—and counting. If the US is a bellwether of a global tendency for public safety agencies to add drones to their “peace arsenal,” the question remains whether this peace is preferable to what was called, once upon a time, by a more recognizable name: war.

Taking recent political unrest in the US and elsewhere into consideration one can fear that the mainstream adoption of drones—under continuing capitalist relations of production—will reinforce rather than challenge existing systems of technologically enabled oppression. It is crucial to remember, as scholar of surveillance Simone Brown notes, that oppressive forms of surveillance did not arrive with new technologies such as drones. Instead, drone surveillance is but a new expression of the same racism and anti-blackness that undergird existing power structures.[74] Whether we are dealing with “ghetto birds” or drones disguised as white peace doves, racist police power is still, to paraphrase James Baldwin, policing black communities like occupied territories.[75] The “sweet dream of perpetual peace,” in other words, still weighs heavily on the brains of the living.[76]

_____

Dominique Routhier is a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the research project Drone Imaginaries and Communities (Independent Research Fund Denmark) at the University of Southern Denmark. His first book With and Against: the Situationist International in the Age of Automation, is forthcoming with Verso Books in 2023.

_____

[1] Jean de La Fontaine, Fables choisies, mises en vers par J. de La Fontaine, vol. 1 (Paris: Desaint and Saillant, 1755), 53, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1049428h.

[2] Shepard Fairey, “Obey Copenhagen Post 1 (Good),” Obey Giant (blog), August 11, 2011, https://obeygiant.com/obey-copenhagen-post-1-good/.

[3] Xan Brooks, Dominic Rushe, and Lars Eriksen, “Shepard Fairey Beaten up after Spat over Controversial Danish Mural,” The Guardian, August 12, 2011, http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/aug/12/shepard-fairey-beaten-danish-mural.

[4] Hito Steyerl, Duty Free Art (New York: Verso, 2017), 1–8.

[5] T. J. Clark, “The Conditions of Artistic Creation,” Times Literary Supplement, May 24, 1974, 562.

[6] The term “image war” has been used in various theoretical contexts since the Gulf War. Perhaps most famously, Jean Baudrillard theorized “the birth of a new kind of military apparatus which incorporates the power to control the production and circulation of images” in a series of essays that appeared in English translation under the title The Gulf War did not take place (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1995), 5. Dora Apel in War Culture and the Contest of Images (New Brunswick: Rutgers Univeristy Press, 2012), W.J.T. Mitchell in Cloning Terror: The War of Images (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2011), and, of course, the Retort collective in Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War (New York: Verso, 2005) all use the term (or corelates) in their analysis of the spectacular nature of late modern warfare.

[7] In terms of methodology, I rely on Otto Karl Werckmeister, Icons of the Left: Benjamin and Eisenstein, Picasso and Kafka after the Fall of Communism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999).

[8] Immanuel Kant, “Toward Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,” in Immanuel Kant, Toward Perpetual Peace and Other Writings on Politics, Peace, and History, ed. Pauline Kleingeld, trans. David L. Colclasure (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 67.

[9] Shepard Fairey, “Manifest Hope,” Obey Giant (blog), August 11, 2008, https://obeygiant.com/manifest-hope/.

[10] For a more detailed historical contextualization of the Youth House, see René Karpantschof and Flemming Mikkelsen, “Youth, Space, and Autonomy in Copenhagen: the Squatters’ and Autonomous Movement, 1963-2012,” in The City is Ours: Squatting and Autonomous Movements from the 1970s to the Present, eds. Bart van der Steen, Ask Katzeff, and Leendert van Hoogenhuijze (Oakland: PM Press, 2014), 179-206.

[11] As chronicled by CrimethInc Ex-Workers Collective, “CrimethInc. : The Battle for Ungdomshuset : The Defense of a Squatted Social Center and the Strategy of Autonomy,” CrimethInc., April 7, 2021, https://crimethinc.com/2019/03/01/the-battle-for-ungdomshuset-the-defense-of-a-squatted-social-center-and-the-strategy-of-autonomy. The following description of the Youth House events relies partly on the account by CrimetInc.

[12] Anna Ringstrom, “Danish Police Battle Protesters,” Reuters, March 3, 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-danish-clashes-1-idUSL0349757520070303.

[13] Kate Connolly, “Tearful Protesters Fail to Save Historic Centre,” The Guardian, March 6, 2007, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/mar/06/topstories3.mainsection.

[14] Shepard Fairey, “Obey Copenhagen Post 2 (Bad),” Obey Giant (blog), August 12, 2011, https://obeygiant.com/obey-copenhagen-post-2-bad/.

[15] Brooks, Rushe, and Eriksen, “Shepard Fairey Beaten up.”

[16] Fairey, “Obey Copenhagen Post 2 (Bad).”

[17] Ibid.

[18] Peter Schjeldahl, “Hope And Glory,” The New Yorker, February 23, 2009, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/02/23/hope-and-glory.

[19] Shepard Fairey, “Thank You, from Barack Obama!,” Obey Giant (blog), March 5, 2008, https://obeygiant.com/check-it-out/.

[20] Kant, “Toward Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,” 67.

[21] “Targeted killing” using drone airstrikes is arguably state assassination by another name. Thanks to Tim Carter for helping me clarify my argument here.

[22] Christi Parsons and W. J. Hennigan, “President Obama, Who Hoped to Sow Peace, Instead Led the Nation in War,” Los Angelses Times, January 13, 2017, http://www.latimes.com/projects/la-na-pol-obama-at-war/.

[23] See, for instance, Joshua Reeves and Matthew S. May, “The Peace Rhetoric of a War President: Barack Obama and the Just War Legacy,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2013, pp. 623-650.

[24] For an excellent discussion of this term in relation to the task of art history, see James Day, “Review Essay: Art History in Its Image War: Ten Recent Publications on Image-Politics in Relation to the Possibility of Art Historical Analysis,” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 24, no. 48 (2015), doi:10.7146/nja.v24i48.23071.

[25] Iain Boal, T. J. Clark, Joseph Matthews, and Michael Watts (Retort), Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War (New York: Verso, 2005), 19.

[26] See Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, trans. Malcolm Imrie (London ; New York: Verso, 1990).

[27] Fairey, “Obey Copenhagen Post 2 (Bad).”

[28] See Ian G. R. Shaw, “The Urbanization of Drone Warfare: Policing Surplus Populations in the Dronepolis,” Geographica Helvetica 71, no. 1 (February 15, 2016): 19–28, doi:10.5194/gh-71-19-2016.

[29] Mark Neocleous, War Power, Police Power (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014).

[30] Ibid., 90.

[31] Ibid., 90.

[32] Ibid., 221n3.

[33] “The Nobel Peace Prize 2009,” NobelPrize.Org, accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2009/press-release/.

[34] Stephanie Busari and Claire Barthelemy, “Obama Peace Prize Win Polarizes Web,” CNN World, accessed April 21, 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/10/09/obama.nobel.peace.reaction/index.html.

[35] Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President at the Acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize” (Oslo City Hall, Oslo, Norway, December 10, 2009), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-acceptance-nobel-peace-prize.

[36] Daniel Klaidman, Kill or Capture: The War on Terror and the Soul of the Obama Presidency (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 117.

[37] Jessica Purkiss and Jack Serle, “Obama’s Covert Drone War in Numbers: Ten Times More Strikes than Bush,” The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, January 17, 2017, https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2017-01-17/obamas-covert-drone-war-in-numbers-ten-times-more-strikes-than-bush.

[38] Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President at the Acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize,” December 10, 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-acceptance-nobel-peace-prize.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Grégoire Chamayou, A Theory of the Drone, trans. Janet Lloyd (New York: The New Press, 2015), 35.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ina Cole, “Pablo Picasso and the Development of a Peace Symbol,” Art Times, May/June 2010, https://www.arttimesjournal.com/art/reviews/May_June_10_Ina_Cole/Pablo_Picasso_Ina_Cole.html.

[43] Tate, “Picasso: Peace and Freedom – Exhibition at Tate Liverpool,” Tate, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/picasso-peace-and-freedom.

[44] Sarah Wilson, Picasso/Marx and Socialist Realism in France (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), 131.

[45] Zvonimir Novak, Agit tracts: un siècle d’actions politique et militaire (Les Éditions L’échapée, 2015), 210.

[46] Anastasia Karel, “Brief History of Paix et Liberté,” Princeton University Libraries, accessed February 11, 2021, http://infoshare1.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/mudd/online_ex/paix/.

[47] Novak, Agit tracts, 210.

[48] See Otto Karl Werckmeister, Icons of the Left: Benjamin and Eisenstein, Picasso and Kafka after the Fall of Communism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 78.

[49] Wilson, Picasso/Marx, 132.

[50] Karel, “Brief History of Paix et Liberté.”

[51] Novak, Agit tracts, 207.

[52] Wilson, Picasso/Marx, 142.

[53] Ibid., 122.

[54] Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?,” The National Interest, no. 16 (1989): 3.

[55] Ibid., 4.

[56] Ibid., 18.

[57] Spencer Ackerman, “Weird, Birdlike Mystery Drone Crashes in Pakistan,” Wired, August 29, 2011, https://www.wired.com/2011/08/weird-birdlike-mystery-drone-crashes-in-pakistan/.

[58] David Cenciotti, “New Images of the Mystery Bird-like Drone Crashed in Pakistan. Taken in Iraq,” The Aviationist, September 14, 2012, https://theaviationist.com/2012/09/14/bird-drone/.

[59] Heba Y. Amin, General’s Stork (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2020), 137.

[60] Kelsey D. Atherton, “Amazon Patent Lets Drones Perch On Streetlight Recharging Stations | Popular Science,” Popular Science, July 20, 2016, https://www.popsci.com/amazon-patent-puts-drones-on-streetlight-recharging-stations/.

[61] Kate Baggaley, “Forget Props and Fixed Wings: New Bio-Inspired Drones Mimic Birds, Bats and Bugs,” NBC News, July 30, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/forget-props-fixed-wings-new-bio-inspired-drones-mimic-birds-ncna1033061.

[62] Eric Chang et al., “Soft Biohybrid Morphing Wings with Feathers Underactuated by Wrist and Finger Motion,” Science Robotics 5, no. 38 (January 16, 2020), doi:10.1126/scirobotics.aay1246.

[63] The “animal prehistory” of drone technology is comparatively well-rehearsed, see Stubblefield, Drone Art, especially chapter 4, “The Animal Remainder: Excavating Nohuman Life from Contemporary Drones.”

[64] Anthony Downey, “Drone Technologies and the Future of Surveillance in the Middle East” (interview with Heba Y. Amin), The MIT Press Reader, January 6, 2021, https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/drone-technologies-future-of-surveillance-middle-east/.

[65] “Drones Dazzle at Disney World in a New Holiday Show,” USA Today, accessed April 14, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/experience/america/theme-parks/2016/12/20/disney-springs-holiday-drone-show-starbright-holidays/95628500/.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Andrea Miller, “Shadows of War, Traces of Policing: The Weaponization of Space and the Sensible in Preemption,” in Captivating Technology: Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life, ed. Ruha Benjamin (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 86.

[68] For an excellent analysis of Joe Biden’s drone fireworks in the shifting historical context of drones, see Caren Kaplan “Everyday Militarisms: Drones and the Blurring of the Civilian-Military Divide During COVID-19” Forthcoming in Drone Aesthetics: War, Culture, Ecology, eds. Michael Richardson and Beryl Pong, Open Humanities Press.

[69] A more recent incident in France testifies to Fairey’s continued commitment to the liberal cause and his knack for appealing to world leaders with his propaganda art. Briefly told, Fairey painted a gigantic Marianne-mural, that, in an echo of the 2011 Copenhagen incident, was destroyed by anonymous graffiti artists. See HIYA! Rédaction, “Un Crew Anonyme Fait «pleurer» La plus Grande Marianne de France! #MariannePleure,” HIYA!, December 14, 2020, https://hiya.fr/2020/12/14/inedit-un-crew-anonyme-fait-pleurer-la-plus-grande-marianne-de-france-mariannepleure/.

[70] Warner Todd Huston, “End Of a Fairey Tale: Poster Artist Says Obama’s Drones Killed ‘Hope,’” Wizbang, October 1, 2013, https://www.wizbangblog.com/2013/10/01/end-of-a-fairey-tale-poster-artist-says-obamas-drones-killed-hope/.

[71] Hunter Schwarz, “The HOPE Poster Guy is Done with Obama. And Republicans Now Have Their Metaphor,” Washington Post, May 28, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/05/28/the-hope-poster-guy-just-handed-republicans-their-ideal-metaphor-for-obamas-presidency/.

[72] For a forthcoming analysis of “late capitalist fascism,” see Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, Late Capitalist Fascism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022).

[73] See for instance the self-declared international movement “Birds Aren’t Real,” which absurdly claims that all birds are government-controlled drones. Whether or not these “activists” are serious about their claims is hard to tell.

[74] Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 8.

[75] James Baldwin, “A Report from Occupied Territory,” July 11, 1966, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/report-occupied-territory/.

[76] I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and insightful criticisms that have helped me greatly improve this essay.

_____

Works Cited

- Ackerman, Spencer. “Weird, Birdlike Mystery Drone Crashes in Pakistan.” Wired. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.wired.com/2011/08/weird-birdlike-mystery-drone-crashes-in-pakistan/.

- Amin, Heba Y. General’s Stork. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2020.

- Apel, Dora. War Culture and the Contest of Images. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

- Atherton, Kelsey D. “Amazon Patent Lets Drones Perch On Streetlight Recharging Stations | Popular Science.” Popular Science. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.popsci.com/amazon-patent-puts-drones-on-streetlight-recharging-stations/.

- Baggaley, Kate. “Forget Props and Fixed Wings. New Bio-Inspired Drones Mimic Birds, Bats and Bugs.” NBC News. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/forget-props-fixed-wings-new-bio-inspired-drones-mimic-birds-ncna1033061.

- Baldwin, James. “A Report from Occupied Territory,” July 11, 1966. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/report-occupied-territory/.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995.

- Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

- Busari, Stephanie, and Claire Barthelemy. “Obama Peace Prize Win Polarizes Web.” CNN World. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/10/09/obama.nobel.peace.reaction/index.html.

- Cenciotti, David. “New Images of the Mystery Bird-like Drone Crashed in Pakistan. Taken in Iraq.” The Aviationist, September 14, 2012. https://theaviationist.com/2012/09/14/bird-drone/.

- Chamayou, Grégoire. A Theory of the Drone. Translated by Janet Lloyd. New York: The New Press, 2015.

- Chang, Eric, Laura Y. Matloff, Amanda K. Stowers, and David Lentink. “Soft Biohybrid Morphing Wings with Feathers Underactuated by Wrist and Finger Motion.” Science Robotics 5, no. 38 (January 16, 2020). doi:10.1126/scirobotics.aay1246.

- Clark, T.J. “The Conditions of Artistic Creation.” Times Literary Supplement, May 24, 1974, 561–62.

- Cole, Ina. “Pablo Picasso and the Development of a Peace Symbol.” Art Times, June 2010. https://www.arttimesjournal.com/art/reviews/May_June_10_Ina_Cole/Pablo_Picasso_Ina_Cole.html.

- Collective, CrimethInc Ex-Workers. “CrimethInc. : The Battle for Ungdomshuset : The Defense of a Squatted Social Center and the Strategy of Autonomy.” CrimethInc. Accessed April 7, 2021. https://crimethinc.com/2019/03/01/the-battle-for-ungdomshuset-the-defense-of-a-squatted-social-center-and-the-strategy-of-autonomy.

- Connolly, Kate. “Tearful Protesters Fail to Save Historic Centre.” The Guardian, March 6, 2007. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/mar/06/topstories3.mainsection.

- Day, James. “Review Essay: Art History in Its Image War. Ten Recent Publications on Image-Politics in Relation to the Possibility of Art Historical Analysis.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 24, no. 48 (2015). doi:10.7146/nja.v24i48.23071.

- Debord, Guy. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Malcolm Imrie. London ; New York: Verso, 1990.

- Downey, Anthony, and Heba Y. Amin. “Drone Technologies and the Future of Surveillance in the Middle East: Heba Y. Amin and Anthony Downey in Conversation.” THe MIT Press Reader, January 6, 2021. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/drone-technologies-future-of-surveillance-middle-east/.

- “Drones Dazzle at Disney World in a New Holiday Show.” USA Today. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/experience/america/theme-parks/2016/12/20/disney-springs-holiday-drone-show-starbright-holidays/95628500/.

- Fairey, Shepard. “Manifest Hope.” Obey Giant, August 11, 2008. https://obeygiant.com/manifest-hope/.

- ——. “Obey Copenhagen Post 1 (Good).” Obey Giant, August 11, 2011. https://obeygiant.com/obey-copenhagen-post-1-good/.

- ——. “Obey Copenhagen Post 2 (Bad).” Obey Giant, August 12, 2011. https://obeygiant.com/obey-copenhagen-post-2-bad/.

- ——. “Thank You, from Barack Obama!” Obey Giant, March 5, 2008. https://obeygiant.com/check-it-out/.

- Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History?” The National Interest, no. 16 (1989): 3–18.

- Huston, Warner Todd. “End Of a Fairey Tale: Poster Artist Says Obama’s Drones Killed ‘Hope.’” Wizbang, October 1, 2013. https://www.wizbangblog.com/2013/10/01/end-of-a-fairey-tale-poster-artist-says-obamas-drones-killed-hope/.

- Joshua Reeves and Matthew S. May. “The Peace Rhetoric of a War President: Barack Obama and the Just War Legacy.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 16, no. 4 (2013): 623. doi:10.14321/rhetpublaffa.16.4.0623.

- Kant, Immanuel. Toward Perpetual Peace and Other Writings on Politics, Peace, and History. Edited by Pauline Kleingeld. Translated by David L. Colclasure. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Kaplan, Caren. “Everyday Militarisms: Drones and the Blurring of the Civilian-Military Divide During COVID-19.” In Drone Aesthetics: War, Culture, Ecology, edited by Michael Richardson and Beryl Pong. Open Humanities Press, Forthcoming.

- Karel, Anastasia. “Brief History of Paix et Liberté.” Princeton University Libraries. Accessed February 11, 2021. http://infoshare1.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/mudd/online_ex/paix/.

- Karpantschof, René, and Flemming Mikkelsen. “Youth, Space, and Autonomy in Copenhagen: The Squatters’ and Autonomous Movement, 1963-2012.” In The City Is Ours: Squatting and Autonomous Movements in Europe from the 1970s to the Present, edited by Bart van der Steen, Ask Katzeff, and Leendert van Hoogenhuijze, 179–206. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2014.

- Klaidman, Daniel. Kill or Capture: The War on Terror and the Soul of the Obama Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

- La Fontaine, Jean de. Fables choisies. Tome 1 / , mises en vers par J. de La Fontaine. Tome premier, 1755. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1049428h.

- Miller, Andrea. “Shadows of War, Traces of Policing: The Weaponization of Space and the Sensible in Preemption.” In Captivating Technology: Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life, edited by Ruha Benjamin, 85–106. Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. Cloning Terror: The War of Images, 9/11 to the Present. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Neocleous, Mark. War Power, Police Power. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

- Novak, Zvonimir. Agit tracts: un siècle d’actions politique et militaire, 2015.

- Obama, Barack. “Remarks by the President at the Acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize.” Oslo City Hall, Oslo, Norway, December 10, 2009. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-acceptance-nobel-peace-prize.

- “Obama’s Covert Drone War in Numbers: Ten Times More Strikes than Bush.” The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2017-01-17/obamas-covert-drone-war-in-numbers-ten-times-more-strikes-than-bush.

- Parsons, Christi, and W. J. Hennigan. “President Obama, Who Hoped to Sow Peace, Instead Led the Nation in War.” Los Angelses Times. Accessed February 4, 2021. http://www.latimes.com/projects/la-na-pol-obama-at-war/.

- Rasmussen, Mikkel Bolt. Late Capitalist Fascism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022.

- Rédaction, HIYA! “Un Crew Anonyme Fait «pleurer» La plus Grande Marianne de France ! #MariannePleure.” HIYA!, December 14, 2020. https://hiya.fr/2020/12/14/inedit-un-crew-anonyme-fait-pleurer-la-plus-grande-marianne-de-france-mariannepleure/.

- Retort (Organization : San Francisco, Calif.). Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War. London ; New York: Verso, 2005.

- Ringstrom, Anna. “Danish Police Battle Protesters.” Reuters, March 3, 2007. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-danish-clashes-1-idUSL0349757520070303.

- Schjeldahl, Peter. “Hope And Glory.” The New Yorker. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/02/23/hope-and-glory.

- Schwarz, Hunter. “The HOPE Poster Guy Is Done with Obama. And Republicans Now Have Their Metaphor.” Washington Post. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2015/05/28/the-hope-poster-guy-just-handed-republicans-their-ideal-metaphor-for-obamas-presidency/.

- Shaw, Ian G. R. “The Urbanization of Drone Warfare: Policing Surplus Populations in the Dronepolis.” Geographica Helvetica 71, no. 1 (February 15, 2016): 19–28. doi:10.5194/gh-71-19-2016.

- “Shepard Fairey Beaten up after Spat over Controversial Danish Mural.” The Guardian, August 12, 2011. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/aug/12/shepard-fairey-beaten-danish-mural.

- Steyerl, Hito. Duty Free Art. London ; New York: Verso, 2017.

- Stubblefield, Thomas. Drone Art: The Everywhere War as Medium. Oakland, California: The University of California Press, 2020.

- Author. 2010. “Title” In Editor, ed. Title. Volume: Issue (Month). Place: Publisher. Pages.

- Tate. “Picasso: Peace and Freedom – Exhibition at Tate Liverpool.” Tate. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/picasso-peace-and-freedom.

- “The Nobel Peace Prize 2009.” NobelPrize.Org. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2009/press-release/.

- Werckmeister, Otto Karl. Icons of the Left: Benjamin and Eisenstein, Picasso and Kafka after the Fall of Communism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Wilson, Sarah. Picasso/Marx and Socialist Realism in France. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.