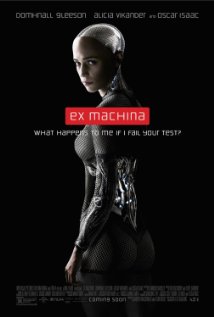

a review of Alex Garland, dir. & writer, Ex Machina (A24/Universal Films, 2015)

a review of Alex Garland, dir. & writer, Ex Machina (A24/Universal Films, 2015)

by Sharon Chang

~

In April of this year British science fiction thriller Ex Machina opened in the US to almost unanimous rave reviews. The film was written and directed by Alex Garland, author of bestselling 1996 novel The Beach (also made into a movie) and screenwriter of 28 Days Later (2002) and Never Let Me Go (2010). Ex Machina is Garland’s directorial debut. It’s about a young white coder named Caleb who gets the opportunity to visit the secluded mountain home of his employer Nathan, pioneering programmer of the world’s most powerful search engine (Nathan’s appearance is ambiguous but he reads non-white and the actor who plays him is Guatemalan). Caleb believes the trip innocuous but quickly learns that Nathan’s home is actually a secret research facility in which the brilliant but egocentric and obnoxious genius has been developing sophisticated artificial intelligence. Caleb is immediately introduced to Nathan’s most upgraded construct–a gorgeous white fembot named Ava. And the mind games ensue.

As the week unfolds the only things we know for sure are (a) imprisoned Ava wants to be free, and, (b) Caleb becomes completely enamored and wants to “rescue” her. Other than that, nothing is clear. What are Ava’s true intentions? Does she like Caleb back or is she just using him to get out? Is Nathan really as much an asshole as he seems or is he putting on a show to manipulate everyone? Who should we feel sorry for? Who should we empathize with? Who should we hate? Who’s the hero? Reviewers and viewers alike are melting in intellectual ecstasy over this brain-twisty movie. The Guardian calls it “accomplished, cerebral film-making”; Wired calls it “one of the year’s most intelligent and thought-provoking films”; Indiewire calls it “gripping, brilliant and sensational”. Alex Garland apparently is the smartest, coolest new director on the block. “Garland understands what he’s talking about,” says RogerEbert.com, and goes “to the trouble to explain more abstract concepts in plain language.”

Right.

I like sci-fi and am a fan of Garland’s previous work so I was excited to see his new flick. But let me tell you, my experience was FAR from “brilliant” and “heady” like the multitudes of moonstruck reviewers claimed it would be. Actually, I was livid. And weeks later–I’m STILL pissed. Here’s why…

*** Spoiler Alert ***

You wouldn’t know it from the plethora of glowing reviews out there cause she’s hardly mentioned (telling in and of itself) but there’s another prominent fembot in the film. Maybe fifteen minutes into the story we’re introduced to Kyoko, an Asian servant sex slave played by mixed-race Japanese/British actress Sonoya Mizuno. Though bound by abusive servitude, Kyoko isn’t physically imprisoned in a room like Ava because she’s compliant, obedient, willing.

I recognized the trope of servile Asian woman right away and, how quickly Asian/whites are treated as non-white when they look ethnic in any way.

Kyoko first appears on screen demure and silent, bringing a surprised Caleb breakfast in his room. Of course I recognized the trope of servile Asian woman right away and, as I wrote in February, how quickly Asian/whites are treated as non-white when they look ethnic in any way. I was instantly uncomfortable. Maybe there’s a point, I thought to myself. But soon after we see Kyoko serving sushi to the men. She accidentally spills food on Caleb. Nathan loses his temper, yells at her, and then explains to Caleb she can’t understand which makes her incompetence even more infuriating. This is how we learn Kyoko is mute and can’t speak. Yep. Nathan didn’t give her a voice. He further programmed her, purportedly, not to understand English.

I started to get upset. If there was a point, Garland had better get to it fast.

Unfortunately the treatment of Kyoko’s character just keeps spiraling. We continue to learn more and more about her horrible existence in a way that feels gross only for shock value rather than for any sort of deconstruction, empowerment, or liberation of Asian women. She is always at Nathan’s side, ready and available, for anything he wants. Eventually Nathan shows Caleb something else special about her. He’s coded Kyoko to love dancing (“I told you you’re wasting your time talking to her. However you would not be wasting your time–if you were dancing with her”). When Nathan flips a wall switch that washes the room in red lights and music then joins a scantily-clad gyrating Kyoko on the dance floor, I was overcome by disgust:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGY44DIQb-A?feature=player_embedded]

I recently also wrote about Western exploitation of women’s bodies in Asia (incidentally also in February), in particular noting it was US imperialistic conquest that jump-started Thailand’s sex industry. By the 1990s several million tourists from Europe and the U.S. were visiting Thailand annually, many specifically for sex and entertainment. Writer Deena Guzder points out in “The Economics of Commercial Sexual Exploitation” for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting that Thailand’s sex tourism industry is driven by acute poverty. Women and girls from poor rural families make up the majority of sex workers. “Once lost in Thailand’s seedy underbelly, these women are further robbed of their individual agency, economic independence, and bargaining power.” Guzder gloomily predicts, “If history repeats itself, the situation for poor Southeast Asian women will only further deteriorate with the global economic downturn.”

You know who wouldn’t be a stranger to any of this? Alex Garland. His first novel, The Beach, is set in Thailand and his second novel, The Tesseract, is set in the Philippines, both developing nations where Asian women continue to be used and abused for Western gain. In a 1999 interview with journalist Ron Gluckman, Garland said he made his first trip to Asia as a teenager in high school and had been back at least once or twice almost every year since. He also lived in the Philippines for 9 months. In a perhaps telling choice of words, Gluckman wrote that Garland had “been bitten by the Asian bug, early and deep.” At the time many Asian critics were criticizing The Beach as a shallow look at the region by an uniformed outsider but Garland protested in his interview:

A lot of the criticism of The Beach is that it presents Thais as two dimensional, as part of the scenery. That’s because these people I’m writing about–backpackers–really only see them as part of the scenery. They don’t see them or the Thai culture. To them, it’s all part of a huge theme park, the scenery for their trip. That’s the point.

I disagree severely with Garland. In insisting on his right to portray people of color one way while dismissing how those people see themselves, he not only centers his privileged perspective (i.e. white, male) but shows determined disinterest in representing oppressed people transformatively. Leads me to wonder how much he really knows or cares about inequity and uplifting marginalized voices. Indeed in Ex Machina the only point that Garland ever seems to make is that racist/sexist tropes exists, not that we’re going to do anything about them. And that kind of non-critical non-resistant attitude does more to reify and reinforce than anything else. Take for instance in a recent interview with Cinematic Essential (one of few where the interviewer asked about race), Garland had this to say about stereotypes in his new film:

Sometimes you do things unconsciously, unwittingly, or stupidly, I guess, and the only embedded point that I knew I was making in regards to race centered around the tropes of Kyoko [Sonoya Mizuno], a mute, very complicit Asian robot, or Asian-appearing robot, because of course, she, as a robot, isn’t Asian. But, when Nathan treats the robot in the discriminatory way that he treats it, I think it should be ambivalent as to whether he actually behaves this way, or if it’s a very good opportunity to make him seem unpleasant to Caleb for his own advantage.

First, approaching race “unconsciously” or “unwittingly” is never a good idea and moreover a classic symptom of white willful ignorance. Second, Kyoko isn’t Asian because she’s a robot? Race isn’t biological or written into human DNA. It’s socio-politically constructed and assigned usually by those in power. Kyoko is Asian because she ha been made that way not only by her oppressor, Nathan, but by Garland himself, the omniscient creator of all. Third, Kyoko represents the only embedded race point in the movie? False. There are two other women of color who play enslaved fembots in Ex Machina and their characters are abused just as badly. “Jasmine” is one of Nathan’s early fembots. She’s Black. We see her body twice. Once being instructed how to write and once being dragged lifeless across the floor. You will never recognize real-life Black model and actress Symara A. Templeman in the role however. Why? Because her always naked body is inexplicably headless when it appears. That’s right. One of the sole Black bodies/persons in the entire film does not have (per Garland’s writing and direction) a face, head, or brain.

“Jade” played by Asian model and actress Gana Bayarsaikhan, is presumably also a less successful fembot predating Kyoko but perhaps succeeding Jasmine. She too is always shown naked but, unlike Jasmine, she has a head, and, unlike Kyoko, she speaks. We see her being questioned repeatedly by Nathan while trapped behind glass. Jade is resistant and angry. She doesn’t understand why Nathan won’t let her out and escalates to the point we are lead to believe she is decommissioned for her defiance.

It’s significant that Kyoko, a mixed-race Asian/white woman, later becomes the “upgraded” Asian model. It’s also significant that at the movie’s end white Ava finds Jade’s decommissioned body in a closet in Nathan’s room and skins it to cover her own body. (Remember when Katy Perry joked in 2012 she was obsessed with Japanese people and wanted to skin one?). Ava has the option of white bodies but after examining them meticulously she deliberately chooses Jade. Despite having met Jasmine previously, her Black body is conspicuously missing from the closets full of bodies Nathan has stored for his pleasure and use. And though Kyoko does help Ava kill Nathan in the end, she herself is “killed” in the process (i.e. never free) and Ava doesn’t care at all. What does all this show? A very blatant standard of beauty/desire that is not only male-designed but clearly a light, white, and violently assimilative one.

I can’t even being to tell you how offended and disturbed I was by the treatment of women of color in this movie. I slept restlessly the night after I saw Ex Machina, woke up muddled at 2:45 AM and–still clinging to the hope that there must have been a reason for treating women of color this way (Garland’s brilliant right?)–furiously went to work reading interviews and critiques. Aside from a few brief mentions of race/gender, I found barely anything addressing the film’s obvious deployment of racialized gender stereotypes for its own benefit. For me this movie will be joining the long list of many so-called film classics I will never be able to admire. Movies where supposed artistry and brilliance are acceptable excuses for “unconscious” “unwitting” racism and sexism. Ex Machina may be smart in some ways, but it damn sure isn’t in others.

Correction (8/1/2015): An earlier version of this post incorrectly stated that actress Symara A. Templeman was the only Black person in the film. The post has been updated to indicate that the movie also featured at least one other Black actress, Deborah Rosan, in an uncredited role as Office Manager.

_____

Sharon H. Chang is an author, scholar, sociologist and activist. She writes primarily on racism, social justice and the Asian American diaspora with a feminist lens. Her pieces have appeared in Hyphen Magazine, ParentMap Magazine, The Seattle Globalist, on AAPI Voices and Racism Review. Her debut book, Raising Mixed Race: Multiracial Asian Children in a Post-Racial World, is forthcoming through Paradigm Publishers as part of Joe R. Feagin’s series “New Critical Viewpoints on Society.” She also sits on the board for Families of Color Seattle and is on the planning committee for the biennial Critical Mixed Race Studies Conference. She blogs regularly at Multiracial Asian Families, where an earlier version of this post first appeared.

The editors thank Dorothy Kim for referring us to this essay.