a review of Jonathan Sterne, Diminished Faculties: A Political Phenomenology of Impairment (Duke UP, 2022)

Somewhere between 500,000 and over 1 million Americans, and many more people worldwide, are now living with some form of post-viral symptomatology from COVID-19—or “Long COVID.” In a pandemic first and pervasively represented by elderly death or “mild” cases no worse than the flu, there are, in reality, three true outcomes after contracting the virus, one of which includes long-term illness, impairment, and disability. These “long haulers” are discovering what disability activists have long known and fought against: accommodation and access are not readily forthcoming, insurance is a nightmare, and people of color and women are much less likely to have their symptoms taken seriously enough to lead to a medical diagnosis. And medical diagnosis, if received, is fraught, too. If 1 in 4 Americans is already disabled, we have been and continue to be living through what some are calling a mass disabling event, akin to a war. This situation is not limited to the circulation of a virus and its aftermath in individual persons and bodies; it extends to the conditions past and present that have produced its lethality: capitalism and its attendants, including medical redlining, environmental racism, settler-colonialism.

Jonathan Sterne’s Diminished Faculties: A Political Phenomenology of Impairment arrives then just in time to complicate that history via the experience of impairment (as well as its kin experiences and identities, illness and disability). As Sterne writes, “The semantic ambiguity among impairment, disability, and illness remains a constitutive feature of all three categories. They move through the same space and bump into one another, sometimes overlapping, sometimes repelling. All three are conditioned by a divergence from medical or social norms. All three are conditioned by an ideology of ability and a preference for ability and health.” Sterne’s book doesn’t just map the experiences of impairment, he also troubles the binary of disabled and able body/mind. By thinking about impairment and faculties, Sterne upends our received notion that we, somehow, are in control of our senses (or our minds, our limbs). Instead, some forms of impairment are accepted, even become norms, while others present as problems. Sterne’s book is about many kinds of impairment, and their intersections in subjects who are understood to be normative nonetheless or even because they’re impaired; what we think of as normal (gradual hearing loss as we work, listen to music, age) versus what is marked off as different and constitutes an unquestioned disability (e.g., childhood deafness following viral illness).

Early in the book, Sterne quotes the disability studies adage, “you will someday join us.” This definitive book is also Sterne’s personal story of living in the matrixes of illness, impairment, and disability, in the materiality of their experience as well as the cultures that contain and produce those experiences. Rather than presenting a work at the end of learning, deleting all the traces of theorization up until the point of arrival, Sterne fully tells the story of how he “joined”: from study groups to blog posts, across changes in understanding and bodily experience. Diminished Faculties therefore provides a rigorous, moving account of the experience of the normal and the pathological, the accounted-for body both disabled and abled, and the one shoved to the margins. Sterne also offers his reader the account of impairment via a political phenomenology grounded in his own story while moving slowly and responsibly beyond it to reconceive impairment theory as a theory of labor, of media, and fundamentally, of political experience.

Sterne is a preeminent voice in Media Studies, and the author of The Audible Past (Duke UP, 2003) and MP3: The Meaning of a Format (Duke UP, 2012). Diminished Faculties is his first book in nearly a decade, the third in a series of works that have shaped and reshaped sound studies, and the first to center his own history.

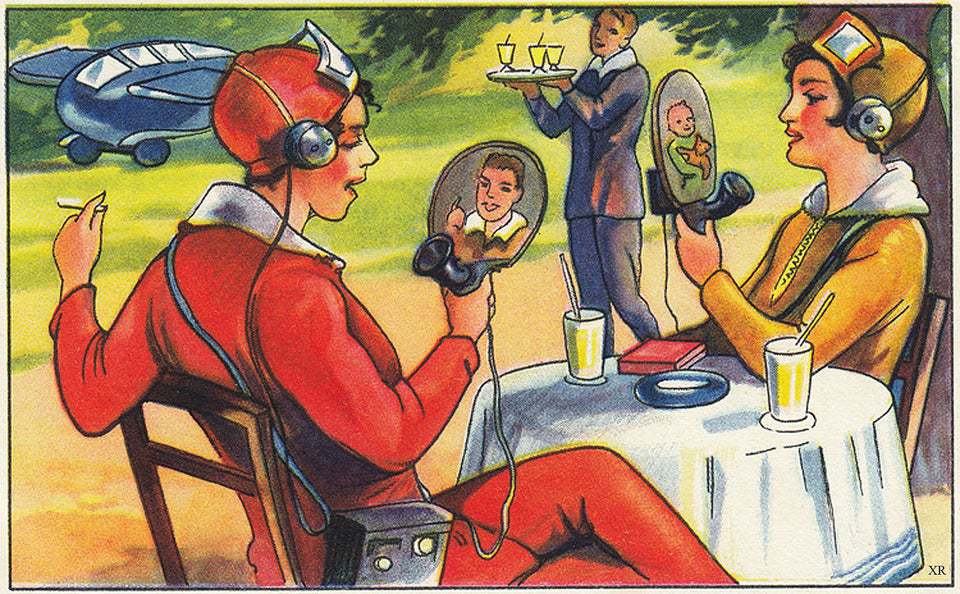

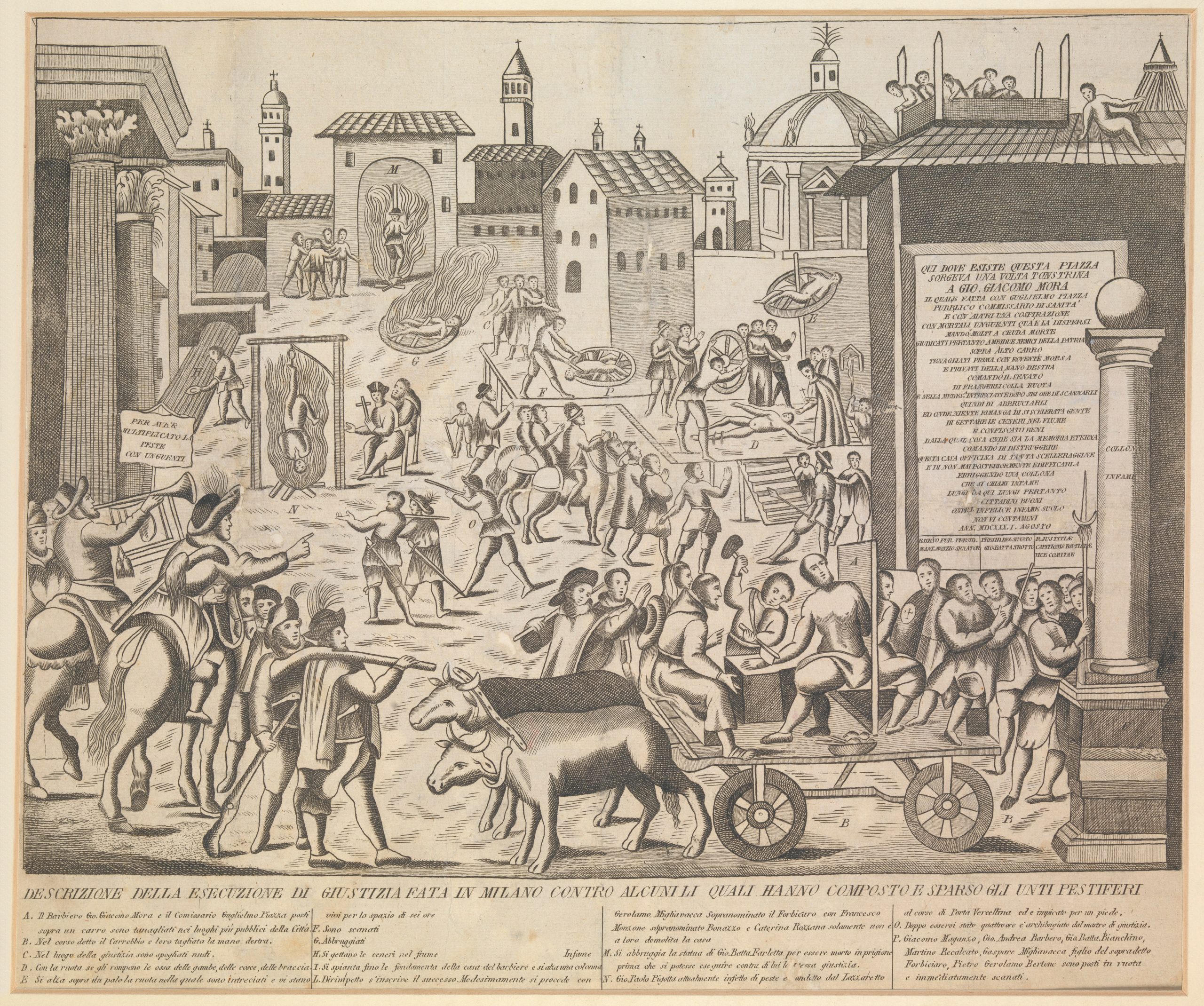

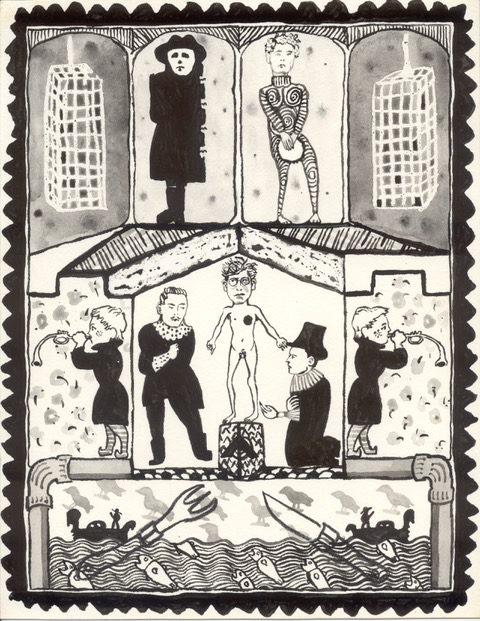

While in this way, Diminished Faculties is moving beyond his previous books to auto-theory, If The Audible Past begins with the “Hello” of the telephone, Diminished Faculties takes on another, amplified greeting. In 2009, Sterne was diagnosed with an aggressive case of thyroid cancer; the surgery to remove his tumor (the size of a pomegranate, as demonstrated in a drawing from S. Lochlann Jain) paralyzed one of his two vocal cords. Normal vocal cord functioning looks like, as Sterne puts it elsewhere “a monkey crashing cymbals”; a normative voice depends on that coordinated cooperation between halves. And as he tells us, his voice may sound better, whatever that really means, to his listener (smokey and rich) on one of his worst days. But Sterne also talks for a living—teaching and delivering research-and his voice blows out, he gets exhausted. As Sterne began vocal therapy, he started to use a personal amplification device that hangs from his neck, which he has termed his “dork-o-phone.” Staying with the example of what gets made visible as impairment, Sterne tells the story of someone coming to a house party, pointing to his chest and saying, “What the fuck is that?” Sterne replies: “Glasses for my voice.” This book tries, in part, to account for this importunate reaction, reconciling a moment of surprise or frustration or intolerance with the fact that impairment is everywhere, and tracking what that reaction does to the subject who is marked as other. As Sterne writes, “Think of all the moving parts in that scenario: a subject whose body cannot match its will; but also auditors struggling to align themselves with whatever techniques the speaker is using. Everyone is trying; nobody is quite succeeding.”

This is one way of naming the book’s method: “think of all the moving parts.” Each of its chapters weaves disability studies, auto-theory, history of science, and media history, turning the levels up or down on any particular input and frame. Diminished Faculties ushers the reader through these interlinked hermeneutics toward a redescription of impairment in the long 20th century.

The first chapter, “Degrees of Muteness,” offers a deep consideration of the uses of phenomenology, and its methods for describing experience, centered on Sterne’s diagnosis, surgery, and its aftermath. As Sterne writes, “this book begins with consciousness of unconsciousness (or is it unconsciousness of consciousness?)” Here he also introduces a media theory of acquired impairment, arguing that, “the concept of impairment is itself also a media concept. The contemporary concept of normal hearing emerged out of the idea of communication impairments and from a very specific time and place.” He moves from this study of a phenomenology of impairment into its deployment, to consider his own voice, or voices v (spoken, amplified, written, authorial). Via his personal amplification device, which he has named the “dork-o-phone,” Sterne takes this object to think with to give us a history and experience of assistive technology and design as it interacts with other infrastructures.

Sterne then moves from political phenomenology to breaking the normative form of a book by inserting the written guide for an imaginary exhibition “In Search of New Vocalities.” The exhibition is accessible, designed for bodies coming from places imaginary and real, an act of care in the scene of art going, if only in the mind. The tone of the book shifts once more for the concluding two chapters towards something more familiar from Sterne’s earlier books, here centered more squarely in STS and Disability studies.

Chapter four is a theorization of Sterne’s identification of “aural scarification” and what he calls normal impairments. In this chapter, Sterne joins recent accounts of the built environment—and here he focuses on our sonic environment—that argue that disability itself reveals aspects of society that hurt everyone, however unevenly. Sara Hendren’s What Can a Body Do? (Riverhead, 2020) shows how the curb on the sidewalk, for example, makes city infrastructures impassable for wheelchair users—but also say, mothers pushing strollers, travelers with suitcases, skateboarders and so on. Add a curb cut and suddenly movement is much more possible in urban spaces for many—not just the conventionally disabled. On the other hand, sometimes access for disabled users is granted almost by accident. Sterne provides another example: closed captioning. Initially, closed captioning was resisted by major broadcast networks precisely because it was expensive and obtrusive—and would only help a small minority. Then other spaces changed and hearing users needed to be able to see what they would otherwise listen to, in airport bars, in hospital waiting rooms, at the gym. Suddenly, D/deaf users got the captions they needed—but only because abled users wanted the same technology. Sterne calls this “crip washing”; the scholar and critic Mara Mills calls this an “assistive pretext.”

Sterne adds to this account that we live in a physical world that is in fact designed for people who are a little bit hearing impaired. Our entire infrastructure is loud: airplanes, bathroom hand dryers, music, whether live or in ear buds. Sterne shows that it is better not to hear perfectly and we hear less well because we interact with this environment; being alive leads to impairment even if we start without it (“you will someday join us”). Throughout Diminished Faculties, Sterne troubles the binary of disabled and abled body/mind by putting disability into a constellation with impairment and illness. By thinking about impairment and faculties, Sterne argues that some forms of impairment are accepted, even become norms, while others are marked as problems, which separates it as a term even as it overlaps with disability. What then is an impairment if we expect it, if it is normal, and it can be disappeared through design? Why are other impairments made visible through these same processes? Considering impairment and disability as a norm is a revision that Sterne requires of his reader, broadening our working understanding of the built environment.

The concluding chapter of the book offers a deft theory and history of fatigue and rest. Opening with theorizations of how we manage fatigue in relation to labor, from Taylorism to energy quantified by “spoons” as theorized by Christine Miserandino, Sterne moves his account of fatigue through and beyond a depletion model. He asks whether we can think of fatigue as something other than a loss, a depletion of energy? He argues that rather than a lack of energy, fatigue is a presence. Sterne reminds his reader throughout that fatigue is so difficult to capture phenomenologically precisely because if it is too overtly present, he couldn’t write it down, if not present enough, he could not articulate the experience of fatigue from within. In this moment, Sterne returns to political phenomenology—including its limits. There are certain experiences, extreme fatigue being one of them—that are sometimes simply not accessible in the moment of writing.

Impairment and fatigue are both concepts from media and the mediation of the body in society, and here are richly positioned within a history of technology and from disability studies. The two commingle, as Sterne deftly shows, to produce our lived experience of body in situ. Along the way, Sterne gives us additional experiences: an account of himself, an exhibition, and a theory to use (and a manual for how we might do it), turn to account, and even dispose of. Diminished Faculties is a lyric, genre-bending book, that is forcefully argued, rendered beautifully, and will open the path for further research. It is deeply generous both to reader and future scholar, as Sterne’s work always is. But additionally, this is a book that so many have needed, and need now, a way of situating the present emergency in a much longer, political history.

_____

Hannah Zeavin teaches in the History and English Departments at UC Berkeley. She is the author of The Distance Cure: A History of Teletherapy (2021, MIT Press). Other work is forthcoming or out from differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Dissent, The Guardian, n+1, Technology & Culture, and elsewhere.