by Mikkel Krause Frantzen

“The situation is bad, yes, okay, enough of that; we know that already. Dystopia has done its job, it’s old news now, perhaps it’s self-indulgence to stay stuck in that place any more. Next thought: utopia. Realistic or not, and perhaps especially if not.

Besides, it is realistic: things could be better.”

(Kim Stanley Robinson)

1. Da capo: The so-called death of utopia and other introductory remarks

Utopia – if not now, when? If not today, tomorrow?

There is a certain tiredness connected to the topic, before the investigation is even begun, a feeling of déjà dit, of having said it all before to the point of utter exhaustion, despair and self-hatred. Yet it seems imperative to continue anyway, to pursue the question once more: What is the fate of utopia today, in this day and age, where there really is no alternative, as Margaret Thatcher infamously declared, and history has (still) ended, as Francis Fukuyama just as triumphantly trumpeted in 1989?

In the midst of economic and ecological crisis it does indeed appear as if the utopian spirit has vanished for good. As far as the (un)real economy is concerned, we are witnessing and living through a fully-fledged state of financialization,[1] characterized by ever more sophisticated forms of fictitious capital: derivatives, futures, options and other products that are traded by algorithms with the speed of lightning (trades are reportedly made in 10 milliseconds or less). After the abolition of Bretton Woods by Nixon in 1971,[2] financial derivatives trading has long since surpassed $100 trillion, and is currently many times the size of the global GDP. Meanwhile, the levels of debt are through the roof. As German scholar Joseph Vogl states in an interview—in an inversion of the famous opening lines from the Communist Manifesto, which he has not only picked up from Don DeLillo’s 2003 novel Cosmopolis but also used as a title for one of his books:

A spectre or an apparition is a present reminder that something has gone awry in our past. A debt has remained unpaid, or a wrong has not been righted. The spectre of capital works the other way around, signaling that something in the future will be wrong. It is a future of mounting debt that comes to weigh on the present. The ‘spectre of capital’ does not come out of the past, but rather as a memento out of the future and back into the present” (Vogl 2011).

This specter of capital, which comes from the future rather than the past, haunts more than the world of finance, it also haunts society as such; the spectral tentacles of financialization reach far into everyday life. One concrete example would be the devastating state of chronic indebtedness that makes people suffer all over the world. Another and related example would be the fact that more and more people are getting depressed; globally no less than 300 million people are currently estimated to suffer from the mental illness according to WHO. And as I have shown elsewhere, depression is not only a personal problem but also and above all a political problem which manifests (or should I say conjures up) the alienation of the contemporary subject in its most extreme and pathological form.[4] It is the paradigmatic psychopathology of our time, and a symptom of a neoliberal world where the future is closed off, frozen once and for all.

In this latest crisis in the cycles of capitalist accumulation, in this season of autumn, if not winter, the future is definitely not what it used to be.[5] As for the imminent ecological disaster, there literally is no future; very soon there is no tomorrow. At all. It should come as little surprise, then, that utopian impulses have seen better days. William Davies writes that there is no “enclave outside the grid” and no “future beyond already emerging trends,” concluding: “The utopia of neoliberalism is the eradication of all utopias” (Davies 2018: 20; 5). Even the harshest critics of neoliberalism and finance capital seem to be caught in a state of left or west melancholy, while other thinkers are all too delighted with having (finally!) arrived in the land of postcritical milk and postutopian honey.[6]

To supplement the hypotheses of the end of history and the end of nature, then: The end of utopia. It is important to note, however, that this song has been sung before. Raymond Aron proclaimed the end of ideology, revolution and utopianism back in 1955, and very similar arguments were made by Judith N. Shklar in After Utopia: The Decline of Political Faith (1957)and Daniel Bell in The End of Ideology (1960), not to mention Christopher Lasch, a couple of decades later, in his bestseller The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations from 1979. In 1989, Fukuyama’s article on the end of history was published, and in 1999 Russell Jacoby wrote The End of Utopia. Politics and Culture in an Age of Apathy, where he lays out this genealogy while at the same time describing how around the turn of the millennium he and his contemporaries “are increasingly asked to choose between the status quo or something worse. Other alternatives do not seem to exist,” how they have “little expectation the future will diverge from the present,” and how few “envision the future as anything but a replica of today” (Jacoby 1999: xi-xii).

Yet there are those who sing a different tune and who insist on the value of utopian thinking (just as there are utopian practices out there).[7] Obviously, Fredric Jameson springs to mind here. In Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire called Utopia and Other Science Fictions from 2005, Jameson, following the work of Ernst Bloch, famously distinguishes between utopia as an impulse and utopia as a program in his general attempt “to reidentify the vital political function Utopia still has to play today”, specifically within the genre of science fiction (Jameson 2005: 21).[8] Also meriting consideration is the political philosopher Miguel Abensour, who passed away in 2017, but whose whole oeuvre was an ongoing analysis and discussion of the continued relevance of utopia in the late 20th and early 21st century through the historical method of revisiting canonical utopian texts, from Thomas More to Saint-Simon, from William Morris to Ernst Bloch. Persistent utopia, he called it in an article of the same name from 2006.

However, it is the book with the no-nonsense title Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin, translated into English in 2017, which this review essay will orbit around. The questions probed by Abensour are the following ones: What does it mean to be a utopian animal in a postutopian age?[9] How do we think utopia in a time of crisis and in the face of danger? Can we find sites where utopia persists, and if so, how are we to interpret them? But the question that also animates my text is a question of historicization and periodization. As indicated above, however briefly, it stands to reason that our historical epoch goes back to the beginning of the 1970s, yet this does not mean that everything has remained the same ever since. So what are the continuities and discontinuities—not only between the age of More, the age of Benjamin and the contemporary age—but also between 2000, when Abensour’s book was originally published in French, and 2018, this year of grace (and here I am in particular thinking of the domains of economy and ecology, the transformations in and of finance and nature)? Let us in any case remember, as Abensour cautions us to do, that utopia precisely poses a question, rather than an answer or a solution (UBM: 10).[10]

2. Between systematic deprecation and uncritical exaltation: Miguel Abensour’s reading of utopian thought in Thomas More and Walter Benjamin

The book Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin is a twofold exegesis; a meditation on, first, Thomas More, and, then, Walter Benjamin. It is as simple as that, although as Abensour admits at the very outset, the two thinkers in question have little in common—except for their contribution to utopian thinking. What this means is that Abensour does not in any way carry out a traditional comparative study. “Rather,” the author writes himself, “the project is one of seizing hold of utopia in two different but powerful moments in its fortunes: the first moment is that of utopia’s beginning, and the second is the moment when utopia faced its greatest danger, the moment that Walter Benjamin called ‘catastrophe’” (UBM:9). Two names, two historical moments: Thomas More and the birth of utopia; Walter Benjamin and the danger and possible death of utopia.

Saving for later a proper actualization of Abensour’s work and the addition of a third historical moment, namely our contemporary moment, about which Abensour more often than not kept his distance, let me simply note that for Abensour it is imperative to avoid two particular and equally untenable positions with regard to utopia: utopia’s “systematic deprecation as well as its uncritical exaltation” (UBM:13). And with that in mind, it is time to hone in on Abensour’s reading of Thomas More, a reading that precisely seeks to avoid praising or damning the book. Sitting with More’s book from 1516 (with the Latin title De Optimo Reipublicae Statu), which coined the word utopia as a play on the Greek words for ou-topia (non-place) and eu-topia (good-place), the reader therefore needs to take into account its “extraordinarily complex textual apparatus” (UBM:20). This implies that attention must be paid to the paratext, the metafictional framework and the oft neglected book I of Utopia—written after the more famous book II—where Raphael Hythloday (another pun), the character/author Thomas More and Peter Giles meet in the Belgian city of Antwerp and starts discussing a series of problems, familiar to any reader of Machiavelli and Plato, concerning the relation between philosophers and kings and how best to offer council to a prince. They also address some of the modern ills affecting Europe at the time: war, poverty, the enclosure of the commons, and the death penalty, which Raphael thinks is too harsh a punishment for a thief (“what other thing do you than make thieves and then punish them?” (More 1999: 24-25). This both sets the scene for and destabilizes book II in advance, the book where Raphael recounts the five years he spent on the Utopia, situated an unknown place in the New World and originally a peninsula but now an island due to the decision of the founder King Utopos to separate it from the mainland. It is here that the readers are rewarded with the image of a true commonwealth, with “no desire for money” and no private property: “For in other places,” Raphael tells his listeners and the readers, “they speak still of the commonwealth. But every man procureth his own private gain. Here, where nothing is private, the common affairs be earnestly looked upon” (More 1999: 119).

Abensour’s claim, however, is that one should refrain from what he calls “the impatience of tyrannical readings,” which in this case implies that one ought to be wary of readings that interpret Utopia as a proper communist commonwealth, i.e. as “prophesying modern communism” (UBM:30; 22). By the same token, any catholic reading that views Utopia as More’s unequivocal defense of “the values of medieval Christian solidarity” is bound to shipwreck (UBM:22). Abensour groups these types of reading under the heading realist readings, which he contrasts with allegorical readings. The former foregrounds the question of politics, while the latter places the question of writing at the center, and the point is that both are wrong. Already it is clear that the utopian question is, for Abensour, a literary question, a question of both writing and reading. The question of politics and the question of literature must be thought alongside each other.

Naturally, any utopia is the stuff of fiction; the very idea of utopia entails an imaginary process of fictionalization or fabulation, and borders as such on the genre of science fiction, which Abensour does not touch on. But Abensour’s book does offer a welcome reminder of the rhetorical and literary character of Utopia, the ways in which it operates in several registers at once (travel narrative, satire, political treatise etc.),and how this in turn creates and conditions the political character of the work: “Utopia, so often presented as one of the most vigorous expressions of political rationalism, in fact has much in common with the ruses of the trickster” (UBM:31). The conclusion Abensour draws from all this, is that the utopian task ultimately, in the last instance so speak, falls to the reader: “The privilege the textual device enjoys has the effect of engaging the reader in a different mode of reading, one separate from a sterile ideological one,” he writes in a passage that demands to be quoted at length:

“It is as if Thomas More, as the title of the book might indicate, did not so much want to present his readers with “the best form of government” as to invite them to look into the topic themselves—and hence the importance of dialogue […] it is a matter of making his readers less into adepts at communism and more into Utopians whose intellects have been sharpened by reading.”

Anyone with some knowledge of French philosophy in the second half of the 20th century will not have a hard time understanding where Abensour is coming from and why he seemingly has such a guarded attitude towards anything that smells even vaguely of ideology and/or communism.[11] A certain distance is needed, which is why More’s utopia, according to Abensour, rests on a double distance: a distance from the existing order and a distance from “the “positivity” whose contours are utopically drawn” (UBM:49). Manifesting a shift “from the solution or the particular program to the level of principle” is critical in that Utopia thereby “introduces plasticity, and prevents us from reading in a certain erroneous manner” (UBM:52). But I wonder if the price to be paid for the distance and ambiguity stressed so much by Abensour is simply too high? You might end up in front of a window so opaque that you cannot look out of it anymore; that you cannot see what is on the other side. The problem is that the utopia Abensour extracts from Thomas More’s book is so saturated with distance that the island risks disappearing from view. The problem is that the “oblique path of utopia” that Abensour also talks about might in fact be so oblique and curvy that you end up right where you started your journey: back on the mainland.[12]

3. Utopia or catastrophe? Walter Benjamin and the utopian dreams of the 19th century

Walter Benjamin, for his part, journeyed to the arcades in the Paris of yesteryear. If More’s Utopia instigated the dawn of utopia, Benjamin’s confronted the danger of utopia: A vision of utopia in the aftermath of the first world war and in the face of fascism across most of Europe. The key question is thus as simple as it is spectacular, if not eschatological: “Utopia or catastrophe?” (UBM:61). The point is clear: We should stick to the idea of utopia, not despite the fact that we are in a state of crisis or amidst a great catastrophe but because of it. As already Kierkegaard emphasized in his writings, hope is only needed when there is none. Utopia seems to have the same absurd and paradoxical quality. The imperative of utopia does not emerge in the hour of triumph, in times so bright that you need sunglasses to go outside; no, the necessity of utopia arises when the light has gone out and everything is completely dark. It is an easy matter to be utopian when everything is all right; the real task presents itself when everything goes to hell. This is one of the lessons that Abensour draws from Benjamin as well: “in the presence of extreme peril, utopia seemed to him more than ever to be the order of the day. In a time of crisis, the need for rescue seemed infinitely greater, and to respond to that need, it seemed best to first rescue utopia by forcing it free from myth and transforming it into a ’dialectical image’” (UBM:13).

How to rescue utopia, and where? In the past. Abensour quotes a letter where Benjamin states that he aims his “telescope through the bloodied mist at a mirage from the nineteenth century” (UBM:10). What he is looking for in the past, especially in the 19th century, is the century’s dream-images (Wunschbilder), fantasies of the epoch, the hidden or veiled utopias, or the ones that were never realized to begin with. In Abensour’s own words, Benjamin is an “incomparable guide” who can help “us penetrate into the unexplored forest of utopias, not in order to give in to their magic, but to hunt down and chase out the mythology or delirium that haunts and destroys them” (UBM:64). From the beginning of his writing to his tragic death in Portbou at the French-Spanish border in 1940, Benjamin remained “intensely sensitive to the utopian vein that is present throughout the century” (UBM:69). Illumination and awakening was the goal, not to stay in the domain of the dream as Aragon and the other surrealists did in Benjamin’s eyes. This is where dialectics and the dialectical image (filled with ambiguity) comes into play, notwithstanding Adorno’s stubborn accusations in their private correspondences that Benjamin was never, ever dialectical enough: a dialectics of dream and awakening, of past and present, of myth and history, of utopia and catastrophe, of revolution and melancholia.[13]

But the future? No. Or to be more precise: The notion of futurity remained an unresolved concept in Benjamin’s work. No need to rehearse his remarks, in Über den Begriff der Geschichte (Theses on the Philosophy of History)from the Spring of 1940, on Klee and Angelus Novus, and the storm called progress that blows the angel of history backwards into the future while the ruins of the past are piling up in front of its eyes (Benjamin 2007, 257-258). Instead, let me concentrate, as Abensour encourages his readers to do, on the textual differences between the two prefaces to Das Passagen-Werk that Benjamin wrote in 1935 and 1939, respectively. The Arcades Project as the work is called in English was Benjamin’s ongoing, unfinished project, spanning more than 10 years, in which he visited the old shopping arcades of Paris, these hubbubs of commerce built of iron and galls and filled with Parisian specialties, luxury products and commodities that abound, in the words of Marx, “in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties” (Marx 2010: 81).

As a comment on a Michelet-quote—“Each epoch dreams the one to follow”—the first so-called exposé of 1935 includes the lines ”in the dream in which each epoch entertains images of its successor, the latter appears wedded to elements of primal history <Urgeschichte> – that is, to elements of a classless society,” and ends with the following sentences: “The realization of dream elements, in the course of waking up, is the paradigm of dialectical thinking. Thus, dialectical thinking is the organ of historical awakening. Every epoch, in fact, not only dreams the one to follow, but, in dreaming, precipitates its awakening.” (Benjamin 1999, 4; 13) All of this was removed by Benjamin in the second exposé, from 1939, perhaps after the ‘advice’ of Adorno. No more references to Michelet, no more avenir, avenir, no more talk of the dialectical image at all (though it figured prominently in the theses on the concept of history a year later). In Abensour’s reading of this transformation, Benjamin opens up a passage from “a conception of history invoking progress (Michelet) to a conception of history under the sign of catastrophe (Blanqui)” (UBM:88). The exposé of ‘39 thus expires in a completely different affective register, with Louis-Auguste Blanqui and his prison book from 1871, Eternity via the Stars. “This book”, according to Benjamin, “completes the century’s constellation of phantasmagorias with one last, cosmic phantasmagoria which implicitly comprehends the severest critique of all the others […] the phantasmagoria of history itself” (Benjamin 1999: 25). Benjamin then goes on to quote an extensive and brilliant paragraph from Blanqui, where the French revolutionary states that “there is no progress” and notes, in a premonition of Nietzsche’s idea of eternal return, “the same monotony, the same immobility, on other heavenly bodies. The universe repeats itself endlessly and paws the ground in place. In infinity, eternity performs—imperturbably—the same routines.” (Benjamin 1999: 26). Without turning, as Abensour writes, Blanqui into an authority, Benjamin’s exposé of 1939 nevertheless ends on this note, in a “resignation without hope” (Benjamin 1999: 26—a line which Abensour also quotes).

As such, the exposé resonates, rather unsurprisingly, with the Theses on the Philosophy of History from the following year. In the preparatory notes, the so-called ‘Paralipomena’, Benjamin repeatedly tries out formulations and ideas such as “Die Katastrophe ist der Fortschritt, der Fortschritt ist die Katastrophe” and “Die Katastrophe als das Kontinuum der Geschichte” (Benjamin 1991: 1244). The true catastrophe is not a break with things as they are; the true catastrophe is, rather, that things go on and on. The progress and continuum of history is history’s catastrophe—whereby the historical and political task becomes one of breaking with this continuum. Benjamin himself writes in some oft-quoted lines about revolution as the moment when you pull the emergency brake on the train of history. Utopia in Benjamin, then, is ultimately intimately and dialectically connected with catastrophe: ““The concept of progress must be founded on the idea of catastrophe,” writes Benjamin. It is the same with the practice of utopia” (101).

4. A new utopian spirit? Five concluding questions to Abensour and the so-called postutopian age

Abensour’s work takes the reader through two names and two historical moments: Thomas More and the dawn of utopia; Walter Benjamin and the dusk of utopia. To this I want to add a third moment, the contemporary moment, our historical age, in which utopia has not so much disappeared as become utterly irrelevant – which is of course far worse. Utopia is not even in a state of extreme peril anymore, it has simply been deemed too insignificant to attract the slightest attention let alone be put in danger, because, from the point of view of utopia’s sworn enemies, whybother?

Unfortunately, Abensour is rather silent on the present moment and more or less refrains from actualizing his historical work, though he does sporadically comment on our anti-utopian age and “contemporary misery,” on the thinkers, “postmodern or otherwise” who want us to abandon emancipation altogether, and on the more general, wide-spread “hatred of utopia, that sad passion eternally reasserted over and over, that repetitive symptom which, generation after generation, afflicts the defenders of the existing order, seized with their fear of alterity” (UBM:61; 15; 12).[14] The motivation for the book is thus clear enough, and the fact that Abensour does not have any more to say, or does not want to say any more, about these contemporary matters is only all the more reason to do this ourselves in this context—without leaving behind his concise and useful definition of utopian thought as being ”beyond this or that particular project,” as it is “essentially a thought about a difference from what currently exists, an uncontrollable, endlessly reborn movement toward a social alterity” (UBM:51). As a way of concluding, then, five utopian questions, five questions to utopia, today. If Benjamin’s exposé of 1939 ended on a significantly darker and gloomier note than the one in 1935, then where do our exposés—the exposés of 2000, 2018, 2028—end? On what notes, in which affective attitudes? Do they end in resignation without hope, or in what Benjamin called, in 1931, Linke Melancholie?[15]

Utopia and time. For all Benjamin’s illuminating thoughts on temporality, our time is not characterized by the “homogenous or empty” time that Benjamin writes about in his theses on the concept of history (Benjamin 2007: 264). By the same token, the problem no longer seems to be the linear, chronological time of historical progress, but rather the heterogenous, loop-like temporality of finance. Today, it is the image of the future, not the past, that “flits by” (“huscht Vorbei”).[16] It is the future that is capsized by capital, pre-emptied in advance by financial speculation and mountains of debt.[17] Yet what would it mean if, accordingly, the political and historical task, the revolutionary and utopian task, becomes one, to modify Benjamin’s thesis 17, of fighting for the oppressed future?[18]

Utopia and fascism. By now we are certainly in a position to appreciate Abensour’s effort to insist that utopia persists and that it is imperative to attend to when and where it, in Benjamin’s formulation, “flashes up at a moment of danger” (Benjamin 2007: 255). Strangely though, Abensour is reluctant to name any real dangers, any concrete catastrophes. His historical work thus remains rather abstract. In fact, he mentions fascism only once in the part on Benjamin and at the very end at that—and fascism was the historical danger that tainted everything that Benjamin thought and wrote, not only in 1939, but also in 1935 and much sooner than that.[19] Such an omission is simply untenable, both in itself and in light of the current situation. Of course, there is no need to be excessively contemporary, and we cannot have too a myopic focus on the present. But there is historical continuity at stake here. It is impossible to ignore Brexit and Grexit, the reality-presidency of Donald Trump, the alt-right in America, and the European populist parties to the right of the right such as the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), the Danish People’s Party (DFP), and Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland. The danger of fascism is not a thing of the past. Can we paraphrase Max Horkheimer and say that anyone who does not want to talk about capitalism and fascism must keep his or her silence about utopia too?

Utopia and desire. What Abensour highlights time and again is that utopia is a question of desire (recall, also, the subtitle of Jameson’s book, The Desire called Utopia and Other Science Fictions).[20] In “William Morris: The Politics of Romance,” Abensour writes, “the point is not for utopia […] to assign ‘true’ or ‘just’ goals to desire but rather to educate desire, to stimulate it, to awaken it. Not to assign it a goal to desire but to open a path for it” (Abensour 1999: 145-146). He also states that desire “must be taught to desire, to desire better, to desire more, and above all to desire otherwise” (Abensour 1999: 145-146). The point is not to desire another world, but, as a precondition, to desire otherwise (à désirer autrement) to begin with.[21] This pedagogical endeavor runs like an undercurrent through Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin. In his reading of More, Abensour convinces the reader that More is more interested in the utopian regulation and configuration of desire than in, say, the construction of alternative institutions. Moreover, he discloses that the historical work undertaken by Benjamin was primarily a matter of locating and excavating the dreams and desire of a past epoch, its so-called oneiric dimension, even if or especially when the images of these dreams and desire were already in ruins, in decay or simply buried, dead or alive, which they always were from the vantage point of Benjamin’s melancholic method of allegory. How can we thus understand the question of utopia as a question of education, of learning to desire otherwise, of learning to desire differently, beyond capitalist realism, reproductive futurism and heteronormative moralism – beyond fascism even?

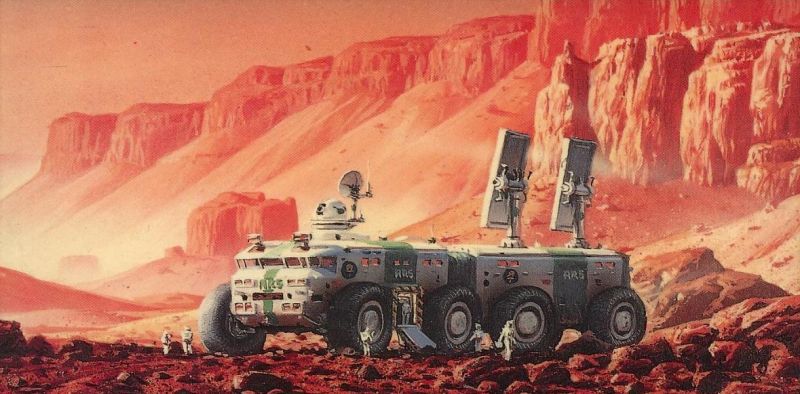

Utopia and dystopia. Of course, there are no guarantees. The desire called utopia can in itself become anti-utopian, or dystopian. William Davies writes, “In our new post-neoliberal age of rising resentments, racisms and walls, the utopian desire to escape can be subverted in all manner of dark directions” (Davies 2018: 28). Which is true: Desire can indeed run in “all manner of dark directions.” It can lead in the opposite direction of what was intended, it can lead straight into a cul-de-sac. It can be perverted, corrupted. Utopias can be cruel, they have their limits, as China Miéville reminds us in his article “The Limits of Utopia.” The utopia of plastic, for instance. Once, plastic was the dream of a new century, a utopian material, from which Russian constructivist Naum Gabo made a sculpture more or less a hundred years ago. A cheap, submissive, servile, and yet unbreakable and indestructible material, plastic was quickly mass produced, and thus became an integral part of an everyday life that now was made more colorful, smooth and shining. Yet plastics, as we now know, had a flip side. In the Pacific Ocean, islands of microplastic the size of France float around. Plastic has indeed been transformed from a utopia to a dystopia: An omnipresent, indestructible sign of the ongoing ecological catastrophe. Some of the utopias of the historical avant-gardes have suffered a similar fate: their project of a unification of art and life has long ago been realized by contemporary capitalism, in workplaces all around the western world. Analogously, the interstellar aspirations of the Russian Cosmism—leaving planet Earth, defeating the sun, colonizing Mars, and achieving some form of immortality—live on in a perverted form in Silicon Valley, where venture capitalists like Elon Musk wish to conquer the unknown in a SpaceX-rocket. Yet giving up on utopias altogether is not an option. Addressing the liberal left, Nick Land writes: “Your hopes are our horror story.” Utopias can indeed be toxic, but the loss of utopias can be toxic as well. Hope has a price, but what is the price of having no hope? What kind of horror is hidden in hopelessness?[22]

Utopia and nature. Utopia and nature, utopia and ecology. The question is: How to think utopia on the brink of planetary annihilation. But also: How not to think it? Again, the utopian imperative, or impulse, does not emerge in spite of the factthat we are the end, but because of it. This is the lesson from Ernst Bloch, which Abensour carries on: “True genesis is not at the beginning but at the end” (Bloch 1995: 1376). Abensour does implicitly touch on these matters when writing about More and the privatization of the commons (continued today by the privatization of not only land, but of air, that is to say the Earth’s atmosphere) and about Benjamin’s reading of the Fourierist utopia, which seeks to find a new relation to nature and to ground itself on something else than a (technological) domination and exploitation of it.[23] Another relation to nature, another organization of nature, not dictated by Wall Street and Silicon Valley—which also implies other forms of temporality and technology, other structures of desire, other transformations and configurations of bodies, other kinds of social and sexual reproduction. Can we think of a way to think, not the end of history, the end of nature, or the end of utopia, but a history of the end, a nature of the end, a utopia of the end? A utopia at the very end, at long last? Let us, at all events, leave the “enemies of utopia to sing their favorite old song” (UMB: 52).[24]

Bio

Mikkel Krause Frantzen (b. 1983), PhD, postdoc at the University of Aalborg, Denmark. He is the author the author Going Nowhere, Slow – The Aesthetics and Politics of Depression (Zero Books, 2019). His work has appeared in Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction (2016), Journal of Austrian Studies (2017), Studies in American Fiction (2018), and Los Angeles Review of Books (2018). He has translated William Burroughs’ The Cat Inside and Judith Butler’s Frames of War into Danish, and works, in addition, as a literary critic at the Danish newspaper, Politiken.

References

Abensour, Miguel. 1999. “William Morris: The Politics of Romance.” In Revolutionary Romanticism: A Drunken Boat Anthology, edited and translated by Max Blechman. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 126–61.

—. 2008. “Persistent Utopia.” Constellations, Vol. 15, No. 3: 406-421.

—. 2010. L’Homme est un animal utopique / Utopiques II. Arles, Les Editions de La Nuit.

—. 2017. Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times. London: Verso.

Benjamin, Walter. 1991. Gesammelte Schriften. Band I·3. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

—. 1994.“Left-Wing Melancholy.” In The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

—. 1999. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

—. 2007. Illuminations. Essays and Reflections, Edited by Hannah Arendt and translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books

Berardi, Franco ‘Bifo’. 2011. After the Future. Chico: AK Press, 2011.

—. The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012.

Bloch, Ernst. 1995. The Principle of Hope. Translated by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice and Paul Knight. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Brown, Wendy. 1999. “Resisting Left Melancholy.” boundary 2 Vol. 26, No. 3 (Autumn): 19-27.

Davies, William. 2018. “Introduction to Economic Science Fictions.” Economic Science Fictions. Edited by William Davies. London: Goldsmiths Press: 1-28.

Dienst, Richard. 2017. “Debt and Utopia.” Verso, September 20, 2017, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3401-debt-and-utopia.

Edelman, Lee. 2004. No Future. Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism. London: Zero Books.

Frantzen, Mikkel Krause. 2017. Going Nowhere, Slow – Scenes of Depression in Contemporary Literature and Culture. PhD diss., University of Copenhagen.

Haiven, Max. 2014. Cultures of Financialization. Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jacoby, Russell. 1999. The End of Utopia. Politics and Culture in an Age of Apathy. New York: Basic Books.

Jameson, Fredric. 1994. The Seeds of Time. New York: Columbia University Press.

—. 1997. “Culture and Finance Capital.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Autumn): 246-265.

—. 2005. Archaeologies of the Future. The Desire called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London: Verso.

—. 2016. An American Utopia: Dual Power and the Universal Army. London: Verso.

Keucheyan, Razmig. 2016 Nature is a Battlefield. Towards a Political Ecology. Translated by David Broder. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. 2011. The Making of the Indebted Man. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Levitas, Ruth. 2013.Utopia as Method. The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society. London: London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Marx, Karl. 2010. Capital. Volume I (Marx & Engels: Collected Works, Volume 35). Chadwell Heath: Lawrence & Wishart.

Miéville, China (year unknown). “The Limits of Utopia.” http://salvage.zone/mieville_all.html.

More, Thomas. 1999. Utopia. In Three Early Modern Utopias. Utopia, New Atlantis and The Isle of Pines. Edited by Susan Bruce. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia. The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

Nadir, Christine. 2010. “Utopian Studies, Environmental Literature, and the Legacy of an Idea: Educating Desire in Miguel Abensour and Ursula K. Le Guin.” Utopian Studies, Vol. 21, No. 1: 24-56.

Robinson, Kim Stanley. 2018. “Dystopias Now.” Commune Magazine. https://communemag.com/dystopias-now/.

Shaviro, Steven. 2006. “Prophesies of the present.” Socialism and Democracy, Vol. 20, No. 3: 5-24.

—. 2018. “On Lisa Adkins, The Time of Money.” The Pinocchio Theory, September 21, 2018. http://www.shaviro.com/Blog/?p=1520.

Vogl, Joseph. 2010. The Specter of Capital. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

—. 2011. “Capital and Money are Profane Gods.” The European, November 20, 2018. https://www.theeuropean-magazine.com/joseph-vogl%E2%80%932/370-the-spectre-of-capital.

Wright, Erik Olin. 2010. Envisioning Real Utopias. London:

Verso.

[1]For more on the concept of financialization, see: Vogl 2010: 83; Haiven 2014: 1.

[2]As Jameson and others have warned, we should be careful when invoking the gold standard: “I don’t particularly want to introduce the theme of the gold standard here, which fatally suggests a solid and tangible kind of value as opposed to various forms of paper and plastic (or information on your computer)” (Jameson 1997: 261).

[3]A generalized condition of debt carries with it, to use Maurizio Lazzarato’s phrase, a preemption of the future, i.e. a reduction of “what will be to what is” (Lazzarato 2011: 46).

[4]See Frantzen 2017. I am, of course, standing on the shoulders of Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, who diagnoses the crisis as a crisis in the social imaginations of the future (Berardi 2011; 2012), and the late Mark Fisher who spoke about capitalist realism, i.e. “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (Fisher 2009:2). Substantiating and elaborating on Jameson’s well-known claim that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, both of them have in their own way diagnosed depression as a prevalent symptom of this historical condition in the western world.

[5]Cf. Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power and the Origins of Our Times (1994).

[6]One might think of Rita Felski’s book The Limits of Critique from 2015 and Bruno Latour’s hugely influential article “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?” from 2004.

[7]See Wright 2010.

[8]Some years later, in An American Utopia from 2016, Jameson declared that“utopianism must first and foremost be a diagnosis of the fear of utopia, or of anti-utopianism” (21).

[9]Here I am alluding to Abensour’s L’Homme est un animal utopique / Utopiques II from 2010.

[10]Hereafter Utopia from Thomas More to Walter Benjamin is cited as UBM.

[11]Conversely, it is imperative to remember that utopian is something Marxists traditionally do not want to be. Within the Marxist tradition, the word utopia/utopian has been an insult that Marxists have thrown at people who were deemed to be irresponsible, naïve, unscientific etc. – this has for instance been the case in the longstanding polemics between Marxists and anarchist.

[12]A further and more traditionally academic objection, which does go beyond my field of expertise, is that I am not sure how original his reading of More is (it makes it hard to tell due to the lack of references to existing scholarship, such as the work of Quentin Skinner and Stephen Greenblatt, for instance).

[13]It is worth remembering that Abensour has written a text called “Passages Blanqui: Walter Benjamin entre mélancolie et révolution.”

[14]Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz echoes this sentiment in his book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, where he writes: “The antiutopian critic of today has a well-worn war chest of poststructuralism pieties at her or his disposal to shut down lines of thought that delineate the concept of critical utopianism” (Muñoz 2009: 10). Inspired by Ernst Bloch, Muñoz insists on the categorical value of futurity, hope and utopia for queer theory as such. Among other things, this leads to an important, loyal but critical discussion of Lee Edelman’s influential No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. In the same queer-theoretical vein, Sara Ahmed asks the question: “Can we simply give up our attachment to thinking about happier futures or the future of happiness?” (Ahmed 2010: 161) The answer is no. Queer theory cannot renounce the future, or utopia proper. As Ahmed also writes: “The utopian form might not make the alternative possible, but it aims to make impossible the belief that there is no alternative” (Ahmed 2010, 163).

[15]See Benjamin 1994. See also Brown 1999. A philosophical and political question of optimism versus pessimism lies hidden here, but I plan to venture into this particular matter elsewhere, rehabilitating a project of Blochean optimism too long forgotten or neglected by the left. In passing, I just want to bring to the reader’s attention this paragraph from Razmig Keucheyan’s Nature is a Battlefield, which takes a Benjamin-quote (“The experience of our generation: that capitalism will not die a natural death”) and the optimism of early/earlier Marxist historicism as its point of departure: “The Arcades Project was written between 1927 and 1940. Three-quarters of a century later, Benjamin’s comment takes on another meaning. Firstly, it does so because contemporary critical thought has renounced any sense of optimism. After the tragedies of the twentieth century, it is instead pessimism that rules. Currently the question is rather more that of whether revolutionary forces are capable of carrying forth a project of radical social change, or if such a project instead now belongs to the past” (Keucheyan: 2016,151).

[16]The phrase turns up in the theses on the philosophy of history (Benjamin 2007: 255).

[17]In a blogpost on Verso’ homepage, Richard Dienst asked the question: Utopia or debt (the economic catastrophe of our time)? See: Dienst 2017.

[18]Steven Shaviro struggles with a set of similar concerns. How can we adopt speculative approaches to speculative temporality and futurity, he wrote in a recent blogpost, that are not “subsumed by, and subjected to, the speculative time of finance” (Shaviro 2018)? Having earlier written about that “stubborn strain in 20th-century Marxist thought – especially in the writings of Walter Benjamin and Ernst Bloch – that finds kernels of hope in the strangest places: in historical experiences of catastrophic failure and defeat, in all those old practices that the relentless march of capitalism has rendered obsolete, and even in the most debased and “ideological” moments of life under capitalism itself” (Shaviro 2006)—the examples being the arcades or more modern-day shopping malls—Shaviro’s current project seems to one of scrutinizing to what extent speculative fiction and science fiction, which is also is to say utopian fiction, are concentric with the logic of financial speculation.

[19]For the single reference, see: Abensour 2017: 108.

[20]Cf. “we might think of the new onset of the Utopian process as a kind of desiring to desire, a learning to desire, the invention of the desire called utopia in the first place.” (Jameson 1994: 90).

[21]See also Christine Nadir’s brilliant article on Miguel Abensour and Ursula Le Guin’s science fiction-novels through the prism of utopia and the education of desire (Nadir 2010: 29-30). Another key work in this regard is Ruth Levitas’ Utopia as Method, in which she provides a definition of utopia ”in terms of desire” (Levitas 2013, xiii), and where, consequently, ”[t]he core of utopia is the desire for being otherwise, individually and collectively, subjectively and objectively” (Levitas 2013” xi). But the theoretical trajectory starts and ends with Ernst Bloch who on the very first page of his trilogy The Principle of Hope writes: “It is a question of learning hope.” (Bloch 1995: 3).

[22]I am again relying on and inspired by Miéville’s “The Limits of Utopia.” Moreover, in his foreword to a new edition of More’s Utopia, Miéville writes: “We need utopia, but to try to think utopia, in this world, without rage, without fury, is an indulgence we can’t afford. In the face of what is done, we cannot think utopia without hate.”

[23]Abensour 2017: 88-93; Benjamin 1999: 17 (though the reading only figures in the exposé from 1939).

[24]After completing this review essay, I stumbled across a brilliant text by Kim Stanley Robinson, “Dystopias Now,” which I did not have the time to incorporate into this one, except for the epigraph, which is taken from there, and this illuminating quote, which goes into the Jamesonian distinction between utopia, dystopia, anti-utopia and anti-anti-utopia (like Jameson, Robinson argues for the latter, and I fully agree with that, as should be more than clear at this point): “One way of being anti-anti-utopian is to be utopian. It’s crucial to keep imagining that things could get better, and furthermore to imagine how they might get better. Here no doubt one has to avoid Berlant’s “cruel optimism,” which is perhaps thinking and saying that things will get better without doing the work of imagining how” (Robinson 2018).