I recall almost nothing between the years of 1986 and 1990. Or, I recall only a few things that I recall very well. My first car was a white Datsun B-210 with an END APARTHEID sticker placed carefully on the bumper. It was 1989 or 1990. Once, I drove my English professor somewhere when the car’s interior was unkempt. She seemed too wide for the passenger seat and simultaneously shorter somehow, which embarrassed me. I do not remember what catalyst compelled me to put the END APARTHEID sticker on my car.

1989 or 1990 was after everything had already happened. American colleges and universities had long divested from South Africa. The federal government was on board. I felt outside of the right time.

There is the kind of remembering that heals and provides the material for forgiveness, and there is a kind of forgetting alongside it—the necessary cell-based kind—that can be a psychic savior. I know now that my elliptical memory is likely linked to my body’s habits of self-protection—to close down a part of the mind so that a parallel self might rise up in place of the other (endangered) self. This possibility that the self and the other might inhabit the same body. In order to remember some things, some neuroscientists theorize, you must forget other things. Repetition, of course, assists in memory; thus, I tend to remember things that happened over and over again but not singular events that happened once. Those abundant incidents, then, become one singular incident instead of several separate occurrences.

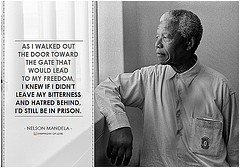

None of us had ever seen him. The photographs on protest placards were taken before he was imprisoned at Robben Island. My first imagining of Mandela was after watching Mandela (1987), the film with Danny Glover and Alfre Woodard. This may have been my first political film. Every imagining of Mandela was interwoven with an image of Glover’s face. The way American cinema exchanges what we know about the world, however perverse that world. At the time, the actual Mandela was in his second of three prisons, Pollsmoor Prison, where he spent extended periods in solitary confinement for six years. In his autobiography, he writes this about solitary: “There is no beginning and no end; there is only one’s mind, which can begin to play tricks. Was that a dream or did it really happen?” How the impulse toward being alive might be broken. Where the mind pinches off like a tourniquet to keep the good blood in a forgetting that is curious and searching, that creates a possibility for survival. What is the self without memory? Forced upon the psyche, the mythos: pastlessness.

That’s what director Steve McQueen says about the world: it’s “perverse.” Artist Kara Walker contends something similar: “What strikes me,” she says, “is how easy it is to commit atrocities.” The monstrosity of blackness presents itself in a side room of the mind. Sometimes we say, “How do I walk with this shadow cast,” and sometimes we say, “I am already looking ahead three paces of where you imagine me to be.” Like many people I know, I have recently had the distressing and arresting experience of watching McQueen’s 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, based on a free black man’s account of being kidnapped and sold into slavery. Removed from the known world. Removed from the known self. What is it to project one’s self apart from the physical body? In the film, the most difficult scene for me to watch is the makeshift funeral for one of the slaves, in which Solomon Northrup, our brutalized protagonist, succumbs to his horrific reality and appears to recognize that the suffering of the others is his as well. But I don’t belong here. At first, while the others sing, he does not. His face is tight, brow furrowed—as if resisting something. Then, he is overtaken and begins to sing too, Roll, Jordan, Roll, a Negro spiritual. His body slumps into itself and, conversely, is also invigorated, or lifted, by the singing.

When there are so many savage beatings in McQueen’s film, so many unimaginable psychic suffocations, why is this the moment that unsettles me most? Perhaps because years go by; he has been looking at his own imagined photo, remembering in precise architecture the self that does not belong in slavery. When he begins to sing, softly at first then more strongly, it’s as if the self Solomon has been holding on to disappears and in his place stands another self, one compelled by abjection. This forgetting of the past self simultaneously grounds him in his present suffering and allows him to reach toward disembodiment and the spiritual realm. This moment within suffering, paradoxically, offers a kind of rescue.

The idea of the abject brings to mind the phrase “to be violently without one’s self.” The singing returns Solomon to a self, though foreign, but what for Mandela? If there is no time, then there is no memory. How did he maintain what appears to be a sense of self unmutated after being removed from the known world, the symbolic order? How to be a body that sustains grace when confronted with the catastrophic? To forget might be to resist claiming and categorizing knowledge. This is the work of the creative artist, I believe, and the opposite of the colonial impulse. I return often to the proposition that perhaps the body, like the self, approaches some unknowability, some forgetting. Was this Spinozan idea that the body resists knowing or, in Deleuze’s estimation, “surpasses the knowledge that we have of it” Mandela’s secret to being uncontained while contained? One of Nelson Mandela’s major contributions to the world is an exalted reference to this infinite body, a reference that afforded him the possibility of remaining unfractured, and to imagine a South Africa theretofore unknown.

–Dawn Lundy Martin