Nelson Mandela was one of the world’s most important twentieth-century political prisoners. At a moment when world politics was in the throes of the “Cold War,” Mandela’s imprisonment focused much of the world’s attention on the authoritarian racial system in South Africa—apartheid.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the white settler country, the Union of South Africa, became independent. By then, South Africa was a society where all the processes of colonialism, its ways of life, its forms of rule, its ideology of white and European supremacy, its construction of African ethnic groups into “natives,” making them nonhuman, had congealed into a specific historical form. As Njabulo Ndebele writes about twentieth-century South Africa, “Everything [in South Africa] has been mind-bogglingly spectacular: the monstrous war machine developed over the years; . . . mass shootings and killings; . . . the mass removals of people; . . . the luxurious life-style of whites. . . . It could be said, therefore, that the most outstanding feature of South African oppression is its brazen, exhibitionist openness.” Apartheid was a regime of death and murder, and as Antjie Krong tells us, deaths were often “so gruesome as to defy the most active imagination.”

It was against this regime of white racial domination, death, and murder that Mandela began his political life. During that life, he was a radical member of the ANC Youth League, a member of the South African Communist Party, an advocate of peaceful confrontation, then of armed struggle. In his early political life, Mandela was an African nationalist with a radical anticolonialist outlook who belonged in the late 1950s and ’60s to that historic cluster of African anticolonial figures. At the same time, he was a courageous figure, one who took physical risks.

It was against this regime of white racial domination, death, and murder that Mandela began his political life. During that life, he was a radical member of the ANC Youth League, a member of the South African Communist Party, an advocate of peaceful confrontation, then of armed struggle. In his early political life, Mandela was an African nationalist with a radical anticolonialist outlook who belonged in the late 1950s and ’60s to that historic cluster of African anticolonial figures. At the same time, he was a courageous figure, one who took physical risks.

For years, the armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the nation), had its headquarters in South Africa, until a South African police raid captured the leadership. At the famous Rivonia trial after the raid, the leadership, including Mandela, all expected to be sentenced to death. Instead, they were sent to Robben Island.

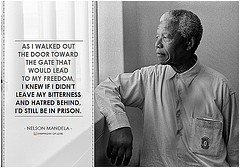

There, during a period Mandela calls the “dark days,” he developed a practice of politics in which moral force was the critical element. The struggles he waged for the dignity of prisoners on Robben Island, the relationships he developed with racist warders, turning them from foes into his “honor guard” when he was allowed to meet his lawyers, were the result of an extraordinary practice of a politics in which human dignity was deployed against brutality, where there was the constant effort to construct a kind of politics in which moral force would force oppression to yield ground. It was the kind of politics in which, as he says, “we fought injustice to preserve our own humanity.” This is a form of politics in which creating a dignified, unbroken self is the most profound of political acts done under the most adverse of conditions.

This kind of politics has a long history in anticolonial and antiracist political practices. Mandela’s practice of politics as a moral force led him to attempt to produce a process of reconciliation and, if possible, justice once the apartheid regime ended. Forgiveness was not a personal matter; rather, it was a political calculation of great risk. Could the politics of moral force bend the beneficiaries of the apartheid regime into themselves taking the risk, not of support for the ANC but of doing the necessary work to build a new South Africa? Nearly twenty years after the 1994 election, which ushered in political equality, this remains one of the unanswered questions of South Africa.

In the politics of moral force, the political personality is central. Mandela was well suited for this role. He had devoted his life to ending the system; he had been jailed for his beliefs and his political practice; he had suffered and therefore had the moral authority to turn that suffering into a political force of change.

The April 1994 election in South Africa was a twentieth-century watershed. When Mandela walked out of jail that day in 1992, the joy many experienced was an acknowledgment that, at long last, the final bastion of racial oppression that had accompanied colonial power was at an end. Mandela was central to that drama, and he represented both the end as well as the possibility of a new beginning. That currently what was seen in South Africa as this exceptional moment of possibility has now stalled gives us all pause and should be generative of new thinking. But in that moment of 1994, in that moment when it seemed that Africa would lead the world in a new way of politics and rule, would redefine politics—in that moment, we remember a possibility, and in that memory we have hope.

I met Mandela twice, once in Jamaica and then again in South Africa on the eve of the 1994 general election. It is the second meeting that stays with me. Late at night in a Johannesburg hotel, he recalled the highlights of the struggle against the apartheid regime. There was nothing about him, not one story of self, in the recounting. Instead, he talked about the young people who were in rebellion in the townships, about Chris Hani, the African general secretary of the South African Communist Party, who had then just been recently assassinated, and about the support given to the ANC and the general Southern African liberation movements by Cuba. The most searching segment of the discussion that night was his preoccupation with the question, what would become of the ANC after the elections? In the room, we were all aware of the fate of twentieth-century national liberation movements in political office, and so there was a robust debate about what could be done in order to ensure that the ANC would not go down that path. This was Mandela the party leader thinking about the possible future of the political party he led. When he left us that night, those of us in the meeting knew that we had been in the presence of a rare political figure, whose every fiber had been honed by one of the central questions of politics, of all politics—how do we construct a just and equal association of humans into a polity?

–Anthony Bogues