Indigenous people are here—here in digital space just as ineluctably as they are in all the other “unexpected places” where historian Philip Deloria (2004) suggests we go looking for them. Indigenous people are on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube; they are gaming and writing code, podcasting and creating apps; they are building tribal websites that disseminate immediately useful information to community members while asserting their sovereignty. And they are increasingly present in electronic archives. We are seeing the rise of Indigenous digital collections and exhibits at most of the major heritage institutions (e.g., the Smithsonian) as well as at a range of museums, universities and government offices. Such collections carry the promise of giving tribal communities more ready access to materials that, in some cases, have been lost to them for decades or even centuries. They can enable some practical, tribal-nation rebuilding efforts, such as language revitalization projects. From English to Algonquian, an exhibit curated by the American Antiquarian Society, is just one example of a digitally-mediated collaboration between tribal activists and an archiving institution that holds valuable historic Native-language materials.

“Digital repatriation” is a term now used to describe many Indigenous electronic archives. These projects create electronic surrogates of heritage materials, often housed in non-Native museums and archives, making them more available to their tribal “source communities” as well as to the larger public. But digital repatriation has its limits. It is not, as some have pointed out, a substitute for the return of the original items. Moreover, it does not necessarily challenge the original archival politics. Most current Indigenous digital collections, indeed, are based on materials held in universities, museums and antiquarian societies—the types of institutions that historically had their own agendas of salvage anthropology, and that may or may not have come by their materials ethically in the first place. There are some practical reasons that settler institutions might be first to digitize: they tend to have rather large quantities of material, along with the staff, equipment and server space to undertake significant electronic projects. The best of these projects are critically self-conscious about their responsibilities to tribal communities. And yet the overall effect of digitizing settler collections first is to perpetuate colonial archival biases—biases, for instance, toward baskets and buckskins rather than political petitions; biases toward sepia photographs of elders rather than elders’ letters to state and federal agencies; biases toward more “exotic” images, rather than newsletters showing Native activists successfully challenging settler institutions to acknowledge Indigenous peoples’ continuous, and political presence.

Those petitions, letters and newsletters do exist, but they tend to reside in the legions of small archives gathered, protected and curated by tribal people themselves, often with gallingly little material support or recognition from outside their communities. While it is true that many Indigenous cultural heritage items have been taken from their source communities for display in remote collecting institutions, it is also true that Indigenous people have continued to maintain their own archives of books, papers and art objects in tribal offices, tribal museums, attics and garages. Such items might be in precarious conditions of preservation, subject to mold, mildew or other damage. They may be incompletely inventoried, or catalogued only in an elder’s memory. And they are hardly ever digitized. A recent survey by the Association of Tribal Archives Libraries and Museums (2013) found that, even though digitization is now the industry standard for libraries and archives, very few tribal collections in the United States are digitizing anything at all. Moreover, the survey found, this often isn’t for lack of desire, but for lack of resources—lack of staff and time, lack of access to adequate equipment and training, lack of broadband.[1]

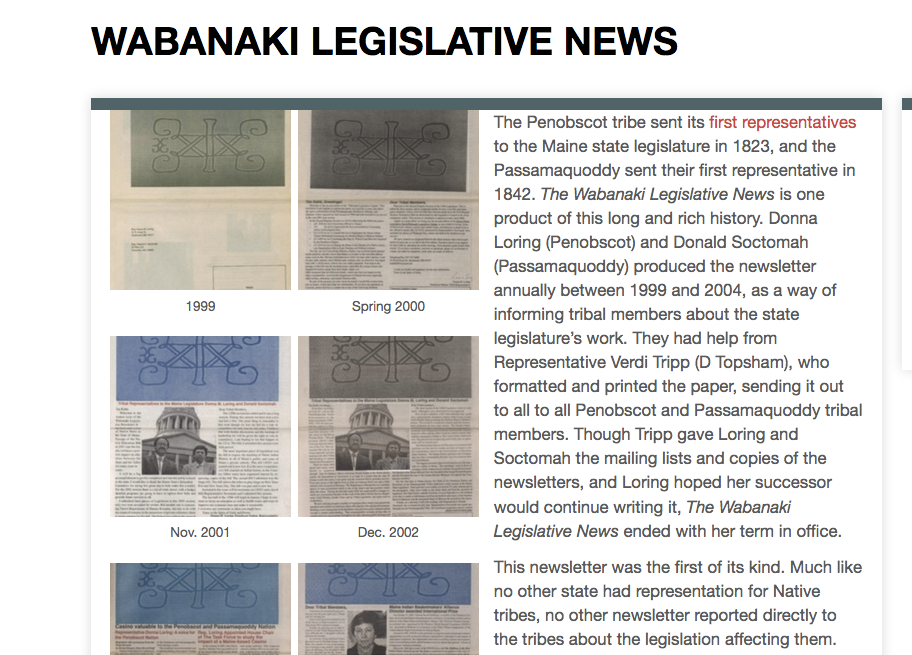

Tribally stewarded collections often hold radically different kinds of materials that tell radically different stories from those historically promoted by institutions that thought they were “preserving” cultural remnants. Of particular interest to me as a literary scholar is the Indigenous writing that turns up in tribal and personal archives: tribal newsletters and periodicals; powwow and pageant programs; mimeographed books used to teach language and traditional narratives; recorded oral histories; letters, memoirs and more. Unlike the ethnographers’ photographs, colonial administrators’ records and (sometimes) decontextualized material objects that dominate larger museums, these writings tell stories of Indigenous survival and persistence. In what follows, I give a brief review of some of the best-known Indigenous electronic archives, followed by a consideration of how digitizing Indigenous writing, specifically, could change the way we see such archives. In their own recirculations of their writings online, Native people have shown relatively little interest in the concerns that currently dominate the field of Digital Humanities, including “preservation,” “open access,” “scalability,” and (perhaps the most unfortunate term in this context) “discoverability.” They seem much keener to continue what those literary traditions have in fact always done: assert and enact their communities’ continuous presence and political viability.

Digital Repatriation and Other Consultative Practices

Indigenous digital archives are very often based in universities, headed by professional scholars, often with substantial community engagement. The Yale Indian Papers Project, which seeks to improve access to primary documents demonstrating the continuous presence of Indigenous people in New England, elicits editorial assistance from a number of Indigenous scholars and tribal historians. The award-winning Plateau People’s Web Portal at Washington State University takes this collaborative methodology one step further, inviting consultants from neighboring tribal nations to come in to the university archives and select and curate materials for the web. Other digital Indigenous exhibits come from prestigious museums and collecting institutions, like the American Philosophical Society’s “Native American Images Project.” Indeed, with so many libraries, museums and archives now creating digital collections these days (whether in the form of e-books, scanned documents, or full electronic exhibits), materials related to Indigenous people can be found in an ever-growing variety of formats and places. Hence, there is also a rising popularity in portals—regional or state-based sites that can act as gateways to a wide variety of digital collections. Some are specific to Indigenous topics and locations, like the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, which compiles web-based resources for studying U.S. boarding school history. Others digital portals sweep up Indigenous objects along with other cultural materials, like the Maine Memory Network or the Digital Public Library of America.

It is not surprising that the bent of most of these collections is decidedly ethnographic, given that Indigenous people the world over have been the subjects of one prolonged imperial looting. Cultural heritage professionals are now legally (or at least ethically) required to repatriate human remains and sacred objects, but in recent years, many have also begun to speak of “digital repatriation.” Just as digital collections of all kinds are providing new access to materials held in far-flung locations, these are arguably a boon to elders or Native people living far away, for instance, from the Smithsonian Museum, to be able to readily view their cultural property. The digitization of heritage and materials can, in fact, help promote cultural revitalization and culturally responsive teaching (Roy and Christal 2002; Srinivasan et al. 2010). Many such projects aim expressly “to reinstate the role of the cultural object as a generator, rather than an artifact, of cultural information and interpretation” (Brown and Nicholas 2012, 313).

Nonetheless, Indigenous people may be forgiven if they take a dim view of their cultural heritage items being posted willy nilly on the internet. Some have questioned whether digital repatriation is a subterfuge for forestalling or refusing the return of the original items. Jim Enote (Zuni), Executive Director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center, has gone so far as to say that the words “digital” and “repatriation” simply don’t belong in the same sentence, pointing out that nothing in fact is being repatriated, since even the digital item is, in most cases, also created by a non-Native institution (Boast and Enote 2013, 110). Others worry about the common assumption that unfettered access to information is always and everywhere an unqualified good. Anthropologist Kimberly Christen has asked pointedly, “Does Information Really Want to be Free?” Her answer: “For many Indigenous communities in settler societies, the public domain and an information commons are just another colonial mash-up where their cultural materials and knowledge are ‘open’ for the profit and benefit of others, but remain separated from the sociocultural systems in which they were and continue to be used, circulated, and made meaningful” (Christen 2012, 2879-80).

A truly decolonized archive, then, calls for a critical re-examination of the archive itself. As Ellen Cushman (Cherokee) puts it, “Archives of Indigenous artifacts came into existence in part to elevate the Western tradition through a process of othering ‘primitive’ and Native traditions . . . . Tradition. Collection. Artifacts. Preservation. These tenets of colonial thought structure archives whether in material or digital forms” (Cushman 2013, 119). The most critical digital collections, therefore, are built not only through consultation with Indigenous knowledge-keepers, but also with considerable self-consciousness about the archival endeavor itself. The Yale editors, for instance, explain that “we cannot speak for all the disciplines that have a stake in our work, nor do we represent the perspective of Native people themselves . . . . [Therefore tribal] consultants’ annotations might include Native origin stories, oral sources, and traditional beliefs while also including Euro-American original sources of the same historical event or phenomena, thus offering two kinds of narratives of the past” (Grant-Costa, Glaza, and Sletcher 2012). Other sites may build this archival awareness into the interface itself. Performing Archive: Curtis + the “vanishing race,” for instance, seeks explicitly to “reject enlightenment ideals of the cumulative archive—i.e. that more materials lead to better, more accurate knowledge—in order to emphasize the digital archive as a site of critique and interpretation, wherein access is understood not in terms of access to truth, but to the possibility of past, present, and future performance” (Kim and Wernimont 2014).

Additional innovations worth mentioning here include the content management system Mukurtu, initially developed by Christen and her colleagues to facilitate culturally responsive archiving for an Aboriginal Australian collection, and quickly embraced by projects worldwide. Recognizing that “Indigenous communities across the globe share similar sets of archival, cultural heritage, and content management needs” (2005:317), Mukurtu lets them build their own digital collections and exhibits, while giving them finely grained control over who can access those materials—e.g., through tribal membership, clan system, family network, or some other benchmark. Christen and her colleague Jane Anderson have also created a system of traditional knowledge (TK) licenses and labels—icons that can be placed on a website to help educate site visitors about the culturally appropriate use of heritage materials. The licenses (e.g., “TK Commercial,” “TK Non-Commercial”) are meant to be legal instruments for owners of heritage material; a tribal museum, for instance, could use them to signal how it intends for electronic material to be used or not used. The TK labels, meanwhile, are extra-legal tools meant to educate users about culturally appropriate approaches to material that may, legalistically, be in the “public domain,” but from a cultural standpoint have certain restrictions: e.g., “TK Secret/Sacred,” “TK Women Restricted,” “TK Community Use Only.”)

All of the projects described here, many still in their incipient stages, aim to decolonize archives at their core. They put Indigenous knowledge-keepers in partnership with computing and heritage management professionals to help communities determine how, whether, and why their collections shall be digitized and made available. As such, they have a great deal to teach digital literary projects—literary criticism (if I may) not being a profession historically inclined to consult with living subjects very much at all. Next, I ponder why, despite great strides in both Indigenous digital collections and literary digital collections, the twain have really yet to meet.

Electronic Textualities: The Pasts and Futures of Indigenous Literature

While signatures, deeds and other Native-authored texts surface occasionally in the aforementioned heritage projects, digital projects devoted expressly to Indigenous writing are relatively few and far between.[2] Granting that Aboriginal people, like any other people, do produce writings meant to be private, as a literary scholar I am confronted daily with a rather different problem than that of cultural “protection”: a great abundance of poetry, fiction and nonfiction written by Indigenous people, much of which just never sees the larger audiences for which it was intended. How can the insights of the more ethnographically oriented Indigenous digital archives inform digital literary collections, and vice versa? How do questions of repatriation, reciprocity, and culturally sensitive contextualization change, if at all, when we consider Indigenous writing?

Literary history is another of those unexpected places in which Indians are always found. But while Indigenous literature—both historic and contemporary—has garnered increasing attention in the academy and beyond, the Digital Humanities does not seem to have contributed very much to the expansion and promotion of these canons. Conversely, while DH has produced some dynamic and diverse literary scholarship, scholars in Native American Studies seem to be turning toward this scholarship only slowly. Perhaps digital literary studies has not felt terribly inviting to Indigenous texts; many observers (Earhart 2012; Koh 2015) have remarked that the emerging digital literary canon, indeed, looks an awful lot like the old one, with the lion’s share of the funding and prestige going to predictable figures like William Shakespeare, William Blake, and Walt Whitman. At this moment, I know of no mass movement to digitize Indigenous writing, although a number of “public domain” texts appear in places like the Internet Archive, Google Books, and Project Gutenberg.[3] Indigenous digital literature seems light years away from the kinds of scholarly and technical standards achieved by the Whitman and Rosetti Archives. And without a sizeable or searchable corpus, scholarship on Indigenous literature likewise seems light years from the kinds of text mining, topic modeling and network analysis that is au courant in DH.

Instead, we see small-scale, emergent digital collections that nevertheless offer strong correctives to master narratives of Indigenous disappearance, and that supply further material for ongoing sovereignty struggles. The Hawaiian language newspaper project is one powerful example. Started as a massive crowdsourcing effort that digitized at least half of the remarkable 100 native-language newspapers produced by Hawaiian people between the 1830s and the 1940s, it calls itself “the largest native-language cache in the Western world,” and promises to change the way Hawaiian history is seen. It might well do so if, as Noenoe Silva (2004, 2) has argued, “[t]he myth of [Indigenous Hawaiian] nonresistance was created in part because mainstream historians have studiously avoided the wealth of material written in Hawaiian.” A grassroots digitization movement like the Hawaiian Nupepa Project makes such studious avoidance much more difficult, and it brings to the larger world of Indigenous digital collections direct examples—through Indigenous literacy—of Indigenous political persistence.

It thus points to the value of the literary in Indigenous digitization efforts. Jessica Pressman and Lisa Swanstrom (2013) have asked, “What kind of scholarly endeavors are possible when we think of the digital humanities as not just supplying the archives and data-sets for literary interpretation but also as promoting literary practices with an emphasis on aesthetics, on intertextuality, and writerly processes? What kind of scholarly practices and products might emerge from a decisively literary perspective and practice in the digital humanities?” Abenaki historian Lisa Brooks (2012, 309) has asked similar questions from an Indigenous perspective, positing that digital space allows us to challenge conventional notions of literary periodization and of place, to “follow paths of intellectual kinship, moving through rhizomic networks of influence and inquiry.” Brooks and other literary historians have long argued that Indigenous people have deployed alphabetic literacy strategically to (re)build their communities, restore and revitalize their traditions, and exercise their political and cultural sovereignty. Digital literary projects, like the Hawaiian newspaper project, can offer powerful extensions of these practices in electronic space.

Dawnlandvoices.org: Curating Indigenous Literary Continuance

These were some of the questions and issues we had in mind when we started dawnlandvoices.org.[4] This archive is emergent—not a straight scan-and-upload of items residing in one physical site or group of sites, but rather a collaboration among tribal authors, tribal collections, and university-based scholars and students. It came out of a print volume, Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Writing from Indigenous New England (Senier 2014), edited by myself and eleven tribal historians. Organized by tribal nation, the book ranges from the earliest writings (petroglyphs and political petitions) to the newest (hip-hop poetry and blog entries). The print volume already aimed to be a counter-archive, insofar as it represents the literary traditions of “New England,” a region that has built its very identity on colonial dispossession, colonial boundaries and the myth of Indian disappearance. It also already aimed to decolonize the archive, insofar as it distributes editorial authority and control to Indigenous writers, historians and knowledge-keepers. At almost 700 pages, though, Dawnland in book form could only scratch the surface of the wealth of writing that regional Native people have produced, and that remains, for the most part, in their own hands.

We wanted a living document—one that could expand to include some of the vibrant pieces we could not fit in the book, one that could be revised and reshaped according to ongoing community conversation. And we wanted to keep presenting historic materials alongside new (in this case born-digital) texts, the better to highlight the long history of Indigenous writing in this region. But we also realized that this required resources. We approached the National Endowment for the Humanities and received a $38,000 Preservation and Access grant to explore how digital humanities resources might be better redistributed to empower tribal communities who want to digitize their texts, either for private tribal use or more public dissemination. The partners on this grant included three different, but representative kinds of collections: a tribal museum with some history of professional archiving and private support (the Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum in Rhode Island); a tribal office that finds itself acting as an unofficial repository for a variety of papers and documents, and that does not have the resources to completely inventory or protect these (the Passamaquoddy Cultural Preservation Office in Maine); and four elders who have amassed a considerable collection of books, papers, and slides from their years working in the Boston Children’s Museum and Plimoth Plantation, and were storing these in their own homes (the Indigenous Resources Collaborative in Massachusetts). Under the terms of the grant, the University of New Hampshire sent digital librarians to each site to set up basic hardware and software for digitization, while training tribal historians in digitization basics. The end result of this two-year pilot project was a small exhibit of sample items from each archive.

The obstacles to this kind of work for small tribal collections are perhaps not unique, but they are intense. Digitization is expensive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive, even more so for collections that do not have ample (or any) paid staff, that can’t afford to update basic software or that don’t even have reliable internet connections. And there were additional hurdles: while the pressure from DH writ large (and granting institutions individually) is frequently to demonstrate scalability, in the end, the tribal partners on this grant did not coalesce around a shared goal of digitizing their collections wholesale. The Passamaquoddy tribal heritage preservation officer has scanned and uploaded the greatest quantity of material by far, but he has strategically zeroed in on dozens of tribal newsletters containing radical histories of Native resistance and survival in the latter half of the twentieth century. The Tomaquag Museum does want to digitize its entire collection, but it prefers to do so in-house, for optimum control of intellectual property. The Indigenous Resources Collaborative, meanwhile, would rather digitize and curate just a small handful of items as richly as possible. While these elders were initially adamant that they wanted to learn to scan and upload their own documents, they learned quickly just how stultifying this labor is. What excited them much more was the process of selecting individual documents and dreaming about how to best share these online. An old powwow flyer describing the Mashpee Wampanoag game of fireball, for instance, had them naming elders and players they could interview, with the possibility of adding metadata in the form of video or narrative audio.

More than a year after articulating this aspiration, the IRC has not begun to conduct or record any such interviews. Such a project is beyond their current energies, time and resources; and to be sure, any continuation of their work on this partner project at dawnlandvoices.org should be compensated, which will mean applying for new grants. But the delay or inaction also points to a larger conundrum: that for all of the Web’s avowed multimodality, indigenous digital collections have generally not reflected the longstanding multimodality of indigenous literatures themselves—in particular, their longstanding and mutually sustaining interplay of oral and written forms. Some (Golumbia 2015) would attribute this to an unwillingness within DH to recognize the kinds of digital language work being done by Indigenous communities worldwide. Perhaps, too, it owes something to the history of violence embedded in “recording” or “preserving” Indigenous oral traditions (Silko 1981); the Indigenous partners with whom I have worked are generally skeptical of the need to put their traditional narratives—or even some of the recorded oral histories they may have stored in cassette—online. Too, there is the time and labor involved in recording. It is now common to hear digital publishers wax enthusiastic about the “affordances” of the Web (it seems so easy, to just add an mp3), but with few exceptions, dawnlandvoices.org has not elicited many recordings, despite our invitations to authors to contribute them.

Unlike the texts in the most esteemed digital literature archives like the Rosetti Archive (edited, contextualized and encoded to the highest scholarly standard), the texts in dawnlandvoices.org are often rough, edgy, and unfinished; and that, quite possibly, is the way they will remain. Insofar as dawnlandvoices.org aspires to be a “database” at all (and we are not sure that it does), it makes sense at this point for there to be multiple pathways in and out of that collection, multiple ways of formatting and presenting material. It is probably fair to say that most scholars working on indigenous digital archives dream of a day when these sites will have robust community engagement and commentary. At the same time, many would readily admit that it’s not as simple as building it and hoping they will come. David Golumbia (2015) has gone so far as to suggest that what marginalizes Indigenous projects within DH is the archive-centric nature of the field itself—that while “most of the major First Nations groups now maintain rich community/governmental websites with a great deal of information on history, geography, culture, and language. . . none of this work, or little of it, is perceived or labeled as DH.” Thus, the esteemed digital archives might not, in fact, be what tribal communities want most. Brown and Nicholas raise the equally provocative possibility that “[i]nstitutional databases may . . . already have been superseded by social networking sites as digital repositories for cultural information” (2012:315). And, in fact, that most pervasive and understandably-maligned of social-networking sites, Facebook, seems to be serving some tribal museums’, authors’ and historians’ immediate cultural heritage needs surprisingly well. Many post historic photos or their own writings to their walls, and generate fabulously rich commentary: identifications of individuals in pictures, memories of places and events, praise and criticism for poetry. Facebook is a proprietary, and notoriously problematic platform, especially on the issue of intellectual property. And yet it has made room, at least for now, for a kind of fugitive curation that, albeit fragile and fugitive, raises the question of whether such curation should be “institutional” at all. We can see similar things happening on Twitter (as in Daniel Heath Justice’s recent “year of tweets” naming Indigenous authors) and Instagram (where artists like Stephen Paul Judd store, share, and comment on their work). Outside of DH and settler institutions, indigenous people are creating all kinds of collections that—if they are not “archives” in a way that satisfy professional archivists—seem to do what Native people, individually and collectively, need them to do. At least for today, these collections create what First Nations artists Jason Lewis and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito call “Aboriginally determined territories in cyberspace” (2005).

What the conversations initiated by Kim Christen, Jane Anderson, Jim Enote and others can bring to digital literature collections is a scrupulously ethical concern for Indigenous intellectual property, an insistence on first voice and community engagement. What Indigenous literature, in turn, can bring to the table is an insistence on politics and sovereignty. Like many literary scholars, I often struggle with what (if anything) makes “Literature” distinctive. It’s not that baskets or katsina masks cannot be read expressions of sovereignty—they can, and they are. But Native literatures—particularly the kinds saved by Indigenous communities themselves rather than by large collecting institutions and salvage anthropologists—provide some of the most powerful and overt archives of resistance and resurgence. The invisibility of these kinds of tribal stories and tribal ways of knowing and keeping stories is an ongoing concern, even on the “open” Web. It may be that Digital Humanities writ large will continue to struggle against the seeming centrifugal force of traditional literary and cultural canons. It is not likely, however, that Indigenous communities will wait for us.

_____

Siobhan Senier is associate professor of English at the University of New Hampshire. She is the editor of Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Writing from Indigenous New England and dawnlandvoices.org.

_____

Notes

[1] A study by Native Public Media (Morris and Meinrath 2009) found that broadband access in and around Native American and Alaska Native communities was less than 10 percent, sometimes as low as 5 to 6 percent.

[2] Two rare, and newer, exceptions include the Occom Circle Project at Dartmouth College, and the Kim-Wait/Eisenberg Collection at Amherst College.

[3] The University of Virginia Electronic Texts Center at one time had an excellent collection of Native-authored or Native-related works, but these are now buried within the main digital catalog.

_____

Works Cited

- Association of Tribal Archives Libraries and Museums. 2013. “International Conference Program.” Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

- Boast, Robin, and Jim Enote. 2013. “Virtual Repatriation: It Is Neither Virtual nor Repatriation.” In Peter Biehl and Christopher Prescott, eds., Heritage in the Context of Globalization. SpringerBriefs in Archaeology. New York, NY: Springer New York. 103–13.

- Brooks, Lisa. 2012. “The Primacy of the Present, the Primacy of Place: Navigating the Spiral of History in the Digital World.” PMLA 127:2. 308–16.

- Brown, Deidre, and George Nicholas. 2012. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property in the Age of Digital Democracy: Institutional and Communal Responses to Canadian First Nations and Māori Heritage Concerns.” Journal of Material Culture 17:3. 307–24.

- Christen, Kimberly. 2005. “Gone Digital: Aboriginal Remix and the Cultural Commons.” International Journal of Cultural Property 12:3. 315–45.

- Christen, Kimberly. 2012. “Does Information Really Want to Be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness.” International Journal of Communication 6. 2870–93.

- Cushman, Ellen. 2013. “Wampum, Sequoyan, and Story: Decolonizing the Digital Archive.” College English 76:2. 116–35.

- Deloria, Philip Joseph. 2004. Indians in Unexpected Places. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- Earhart, Amy. 2012. “Can Information Be Unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon.” In Matt Gold, ed., Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Golumbia, David. 2015. “Postcolonial Studies, Digital Humanities, and the Politics of Language.” Postcolonial Digital Humanities.

- Grant-Costa, Paul, Tobias Glaza, and Michael Sletcher. 2012. “The Common Pot: Editing Native American Materials.” Scholarly Editing 33.

- Kim, David J., and Jacqueline Wernimont. 2014. “‘Performing Archive’: Identity, Participation, and Responsibility in the Ethnic Archive.” Archive Journal 4.

- Koh, Adeline. 2015. “A Letter to the Humanities: DH Will Not Save You.” Hybrid Pedagogy, April 19.

- Lewis, Jason, and Skawennati Fragnito. 2005. “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace.” Cultural Survival (June).

- Morris, Traci L., and Sascha D. Meinrath. 2009. New Media, Technology and Internet Use in Indian Country: Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses. Flagstaff, AZ: Native Public Media.

- Pressman, Jessica, and Lisa Swanstrom. 2013. “The Literary And/As the Digital Humanities” Digital Humanities Quarterly 7:1.

- Roy, Loriene, and Mark Christal. 2002. “Digital Repatriation: Constructing a Culturally Responsive Virtual Museum Tour.” Journal of Library and Information Science 28:1. 14–18.

- Senier, Siobhan, ed. 2014. Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Silko, Leslie Marmon. 1981. “An Old-Time Indian Attack Conducted in Two Parts.” In Geary Hobson, ed. The Remembered Earth: An Anthology of Contemporary Native American Literature. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. 211–16

- Silva, Noenoe K. 2004. Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Srinivasan, Ramesh, et al. 2010. “Diverse Knowledges and Contact Zones within the Digital Museum.” Science Technology Human Values 35:5. 735–68.

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)