In a passage from his 2014 book Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free author and copyright reformer Cory Doctorow sounds a familiar note against strict copyright. “Creators and investors lose control of their business—they become commodity suppliers for a distribution channel that calls all the shots. Anti-circumvention [laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which prohibits subverting controls on the intended use of digital objects] isn’t copyright protection, it’s middleman protection” (50).

This is the specter haunting the digital cultural economy, according to many of the most influential voices arguing to reform or disrupt it: the specter of the middleman, the monopolist, the distortionist of markets. Rather than an insurgency, this specter emanates from economic incumbency: these middlemen are the culture industries themselves. With the dual revolutions of personal computer and internet connection, record labels, book publishers, and movie studios could maintain their control and their profits only by asserting and strengthening intellectual property protections and squelching the new technologies that subverted them. Thus, these “monopolies” of cultural production threatened to prevent individual creators from using technology to reach their audiences independently.

Such a critique became conventional wisdom among a rising tide of people who had become accustomed to using the powers of digital technology to copy and paste in order to produce and consume cultural texts, beginning with music. It was most comprehensively articulated in a body of arguments, largely produced by technology evangelists and tech-aligned legal professionals, hailing from the Free Culture movement spearheaded by Lawrence Lessig. The critique’s practical form was the host of piratical activities and peer-to-peer technologies that, in addition to obviating traditional distribution chains, dedicated themselves to attacking culture industries, as well as their trade organizations such as the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA).

Connected to this critique is an alternate vision of the digital economy, one that leverages new technological commons, peer production and network effects to empower creators. This vision has variations, and travels under a number of different political banners, from anarchist to libertarian to liberal and many more who prefer not to label.[1] It tells a compelling story (one Doctorow has adapted into novels for young people): against corporate monopolists and state regulation, a multitude, empowered by the democratizing effects bequeathed to society by networked personal computers, and other technologies springing from them, is posed to revolutionize the production of media and information, and, therefore, the political and economic structure as a whole. Work will be small-scale and independent, but, bereft of corporate behemoths, more lucrative than in the past.

This paper traces the contours of the critique put forth by Doctorow and other revolutionaries of networked digital production in light of a nineteenth-century thinker who espoused remarkably similar arguments over a century ago: the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Few of these writers are evident readers of Proudhon or explicitly subscribe to his views, though some, such as the Center for Stateless Society do. Rather than a formal doctrine, what I call “Digital Proudhonism” is better understood as what Raymond Williams (1977) calls a “structure of feeling”: a kind of “practical consciousness” that identifies “meanings and values as they are actively lived and felt” (132), in this case, related to specific experiences of networked computer use. In the case under discussion these “affective elements of consciousness and relationships” are often articulated in a political, or at least polemical, register, with real effects on the political self-understanding of networked subjects, the projects they pursue, and their relationship to existing law, policy and institutions. Because of this, I seek to do more than identify currents of contemporary Digital Proudhonism. I maintain that the influence of this set of practices and ideas over the politics of digital production necessitates a critique. In this case, I argue that a return to Marx’s critique of Proudhon will aid us in piercing through the Digital Proudhonist mystifications of the Internet’s effects on politics and industry and reformulate both a theory of cultural production under digital capitalism as well as radical politics of work and technology for the 21st century.

From the Californian Ideology to Digital Proudhonism

What I am calling Digital Proudhonism has precedent in the social critique of techno-utopian beliefs surrounding the internet. It echoes Langdon Winner’s (1997) diagnosis of “cyberlibertarianism” in the Progress and Freedom Foundation’s 1994 manifesto “Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age,” where “the wedding of digital technology and the free market” manages to “realize the most extravagant ideals of classical communitarian anarchism” (15). Above all, it bears a marked resemblance to Barbrook and Cameron’s (1996) landmark analysis of the “Californian Ideology,” that “bizarre mish-mash of hippie anarchism and economic liberalism beefed up with lots of technological determinism” emerging from the Wired (in the sense of the magazine) corners of the rise of networked computers, which claims that digital technology is the key to realizing freedom and autonomy (56). As the authors put it, “the Californian Ideology promiscuously combines the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies. This amalgamation of opposites has been achieved through profound faith in the emancipatory potential of new information technologies” (45).

My contribution will follow the argument of Barbrook and Cameron’s exemplary study. As good Marxists, they recognized that ideology was not merely an abstract belief system, but “offers a way of understanding the lived reality” (50) of a specific social base: “digital artisans” of programmers, software developers, hackers and other skilled technology workers who “not only tend to be well-paid, but also have considerable autonomy over their pace of work and place of employment” (49). Barbrook and Cameron located the antecedents of the Californian Ideology in Thomas Jefferson’s belief that democracy was best secured by self-sufficient individual farmers, a kind of freedom that, as the authors trenchantly note, “was based upon slavery for black people” (59).

Thomas Jefferson is an oft-cited figure among the digital revolutionaries associated with copyright reform. Law professor James Boyle (2008) drafts Jefferson into the Free Culture movement as a fellow traveler who articulated “a skeptical recognition that intellectual property rights might be necessary, a careful explanation that they should not be treated as natural rights, and a warning of the monopolistic dangers that they pose” (21). Lawrence Lessig cites Jefferson’s remarks on intellectual property approvingly in Free Culture (2004, 84). “Thomas Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers were thoughtful, and got it right,” states Kembrew McLeod (2005) in his discussion of the U.S. Constitution’s clauses on patent and copyright (9).

There is a deeper political and economic resonance between Jefferson and internet activists beyond his views on intellectual property. Jefferson’s ideal productive arrangement of society was small individual landowners and petty producers: the yeoman farmer. Jefferson believed that individual self-sufficiency guaranteed a democratic society. The abundance of land in the New World and the willingness to expropriate it from the indigenous peoples living there gave his fantasy a plausibility and attraction many Americans still feel today. It was this vision of America as a frontier, an empty space waiting to be filled by new social formations, that makes his philosophy resonate with the techno-adept described by Barbrook and Cameron, who viewed the Internet in a similar way. One of these Californians, John Perry Barlow (1996), who famously declared to “governments of the Industrial World” that “cyberspace does not lie within your borders,” even co-founded an organization dedicated to a deregulated internet called the “Electronic Frontier Foundation.”

However, not everything online lent itself to the metaphor of a frontier. Particularly in the realm of music and video, artisans dealt with a field crowded with existing content, as well as thickets of intellectual property laws that attempted to regulate how that content was created and distributed. There could be no illusion of a blank canvas on which to project one’s ideal society: in fact, these artisans were noteworthy, not for producing work independently out of whole cloth, but for refashioning existing works through remix. Lawrence Lessig (2004) quotes mashup artist Girl Talk: “We’re living in this remix culture. This appropriation time where any grade-school kid has a copy of Photoshop and can download a picture of George Bush and manipulate his face how they want and send it to their friends” (14). The project of Lessig and others was not to create the conditions for erecting a new society upon a frontier, as a yeoman farmer might, but to politicize this class of artisans in order to challenge larger industrial concerns, such as record labels and film studios, who used copyright to protect their incumbent position. This very different terrain requires a different perspective from Jefferson’s.

Thomas Jefferson’s vision is not the only expression of the fantasy of a society built on the basis of petty producers. In nineteenth-century Europe, where most land had long been tied up in hereditary estates, large and small, the yeoman farmer ideal held far less influence. Without a belief in abundant land, there could be no illusion of a blank canvas on which a new society could be created: some kind of revolutionary change would have to occur within and against the old one. And so a similar, yet distinct, political philosophy sprang up in France among a similar social base of artisans and craftsmen—those who tended to control their own work process and own their own tools—who made up a significant part of the French economy. As they were used to an individualized mode of production, they too believed that self-sufficiency guaranteed liberty and prosperity. The belief that society should be organized along the lines of petty individual commodity producers, without interference from the state—a belief remarkably consonant with a variety of digital utopians—found its most powerful expression in the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. It is to his ideas that I now turn.

What was Proudhonism?

An anarchist and influential member of the International Workingmen’s Association of which Karl Marx was also a part, Proudhon’s ideas were especially popular in his native France, where the economy was rooted far more deeply in small-scale artisanal production than the industrial-scale capitalism Marx experienced in Britain. His first major work, What Is Property? ([1840] 2011) (Proudhon’s pithy answer: property is theft) caught the attention of Marx, who admired the work’s thrust and style, even while he criticized its grasp of the science of political economy. After attempting to win over Proudhon by teaching him political economy and Hegelian dialectics, Marx became a vehement critic of Proudhon’s ideas, which held more sway over the First International than Marx’s own.

Proudhon was critical of the capitalism of his day, but made his criticisms, along with his ideas for a better society, from the perspective of a specific class. Rather than analyze, as Marx did, the contradictions of capitalism through the figure of the proletarian, who possesses nothing but their own capacity to work, Proudhon understood capitalism from the perspective of an artisanal small producer, who owns and labors with their own small-scale means of production. In David McNally’s (1993) survey of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century radical political economy, he summarizes Proudhon’s beliefs. Proudhon “envisages a society [of] small independent producers—peasants and artisans—who own the products of their personal labour, and then enter into a series of equal market exchanges. Such a society will, he insists, eliminate profit and property, and ‘pauperism, luxury, oppression, vice, crime and hunger will disappear from our midst’” (140).

For Proudhon, massive property accumulation of large firms and accompanying state collusion distorts these market exchanges. Under the prevailing system, he asserts in The Philosophy of Poverty, “there is irregularity and dishonesty in exchange” ([1847] 2012, 124) a problem exemplified by monopoly and its perversion of “all notions of commutative justice” (297). Monopoly permits unjust property extraction: Proudhon states in General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century ([1851] 2003) that “the price of things is not proportionate to their VALUE: it is larger or smaller according to an influence which justice condemns, but the existing economic chaos excuses” (228). Exploitation becomes thereby a consequence of market disequilibria—the upward and downward deviations of price from value. It is a faulty market, warped by state intervention and too-powerful entrenched interests that is the cause of injustice. The Philosophy of Poverty details all manner of economic disaster caused by monopoly: “the interminable hours, disease, deformity, degradation, debasement, and all the signs of industrial slavery: all these calamities are born of monopoly” (290).

As McNally’s (1993) work shows, blaming economic woes on “monopolists” and “middlemen” ran rife in popular critiques of political economy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, leading many radicals to call for free trade as a solution to widespread poverty. Proudhon’s anarchism was part of this general tendency. In General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century ([1851] 2003), he railed against “middlemen, commission dealers, promoters, capitalists, etc., who, in the old order of things, stand in the way of producer and consumer” (90). The exploiters worked by obstructing and manipulating the exchange of goods and services on the market.

Proudhon’s particular view of economic injustice begets its own version of how best to change it. His revolutionary vision centers on the end of monopolies and currency reform, two ways that “monopolists” intervened in the smooth functioning of the market. He remained dedicated to the belief that the ills of capitalism arose from the concentrations of ownership creating unjust political power that could further distort the functioning of the market, and envisioned a market-based society where “political functions have been reduced to industrial functions, and that social order arises from nothing but transactions and exchanges” (1979, 11).

Proudhon evinced a technological optimism that Marx would later criticize. From his petty producer standpoint, he believed technology would empower workers by overcoming the division of labor:

Every machine may be defined as a summary of several operations, a simplification of powers, a condensation of labor, a reduction of costs. In all these respects machinery is the counterpart of division. Therefore through machinery will come a restoration of the parcellaire laborer, a decrease of toil for the workman, a fall in the price of his product, a movement in the relation of values, progress towards new discoveries, advancement of the general welfare. ([1847] 2012, 167)

While Proudhon recognized some of the dynamics by which machinery could immiserate workers through deskilling and automating their work, he remained strongly skeptical of organized measures to ameliorate this condition. He rejected compensating the unemployed through taxation because it would “visit ostracism upon new inventions and establish communism by means of the bayonet” ([1847] 2012, 207); he also criticized employing out-of-work laborers in public works programs. Technological development should remain unregulated, leading to eventual positive outcomes: “The guarantee of our liberty lies in the progress of our torture” (209).

Marx’s Critique of Proudhon

Marx, after attempting to influence Proudhon, became one of his most vehement critics, attacking his rival’s arguments, both major and marginal. Marx had a very different understanding of the new industrial society of the nineteenth century. Marx ([1865] 2016) diagnosed his rival’s misrepresentations of capitalism as derived from a particular class basis. Proudhon’s theories emanated “from the standpoint and with the eyes of a French small-holding peasant (later petit bourgeois)” rather than the proletarian, who possesses nothing but labor-power, which must be exchanged for a wage from the capitalist.

Since small producers own their own tools and depend largely on their own labor, they do not perceive any conflict between ownership of the means of production and labor: analysis from this standpoint, such as Proudhon’s, tends to collapse these categories together. Marx’s theorization of capitalism centered an emergent class of industrial proletarians, who, unlike small producers, owned nothing but their ability to sell their labor-power for a wage. Without any other means of survival, the proletarian could not experience the “labor market” as a meeting of equals coming to a mutually beneficial exchange of commodities, but as an abstraction from the concrete truth that working for whatever wage offered was compulsory, rather than a voluntary contract. Further, it was this very market for labor-power that, in the guise of equal exchange of commodities, helped to obscure that capitalist profit depended on extracting value from workers beyond what their wages compensated. This surplus value emerged in the production process, not, as Proudhon argued, at a later point where the goods produced were bought and sold. Without a conception of a contradiction between ownership and labor, the petty producer standpoint cannot see exploitation occurring in production.

Instead, Proudhon saw exploitation occurring after production, during exchanges on the market distorted by unfair monopolies held intact through state intervention, with which petty producers could not compete. However, Marx ([1867] 1992) demonstrated that “monopolies” were simply the outcome of the concentration of capital due to competition: in his memorable wording from Capital, “One capitalist always strikes down many others” (929). As producers compete and more and more producers fail and are proletarianized, capital is held in fewer and fewer hands. In other words, monopolies are a feature, not a bug, of market economies.

Proudhon’s misplaced emphasis on villainous monopolies is part of a greater error in diagnosing the momentous changes in the nineteenth-century economy: a neglect of the centrality of massive industrial-scale production to mature capitalism. In the first volume of Capital, Marx ([1867] 1992) argues that petty production was a historical phenomenon that would give way to capitalist production: “Private property which is personally earned, i.e., which is based, as it were, on the fusing together of the isolated, independent working individual with the conditions of his labour, is supplanted by capitalist private property, which rests on exploitation of alien, but formally free labour” (928). As producers compete and more and more producers fail and are proletarianized, capital—and with it, labor—concentrates.

However, petty production persisted alongside industrial capitalism in ways that masked how the continued existence of the former relies on the latter. Under capitalism, labor, through commodification of labor-power through the wage relationship, is transformed from concrete acts of labor into labor in the abstract in the system of industrial production for exchange. This abstract labor, the basis of surplus value, is for Marx the “specific social form of labour” in capitalism (Murray 2016, 124). Without understanding abstract labor, Proudhon could not perceive how capitalism functioned as not simply a means of producing profit, but a system of structuring all labor in society.

The importance of abstract labor to capitalism also meant that Proudhon’s plans to reform currency by making it worth labor-time would fail. As Marx ([1847] 1973) puts it in his book-length critique of Proudhon, “in large-scale industry, Peter is not free to fix for himself the time of his labor, for Peter’s labor is nothing without the co-operation of all the Peters and all the Pauls who make up the workshop” (77). In other words, because commodities under capitalism are manufactured through a complex division of labor, with different workers exercising differing levels of labor productivity, it is impossible to apportion specific quantities of time to specific labors on individual commodities. Without an understanding of the role of abstract labor to capitalist production, Proudhon could simply not grapple with the actual mechanisms of capitalism’s structuring of labor in society, and so, could not develop plans to overcome it. This overcoming could only occur through a political intervention that sought to organize production from the point of view of its socialization, not, as Proudhon believed, reforming elements of the exchange system to preserve individual producers.

The Roots of Digital Proudhonism

Many of Proudhon’s arguments were revived among digital radicals and reformers during the battles over copyright precipitated by networked digital technologies during the 1990s, of which Napster is the exemplary case. The techno-optimistic belief that the Internet would provide radical democratic change in cultural production took on a highly Proudhonian cast. The internet would “empower creators” by eliminating “middlemen” and “gatekeepers” such as record labels and distributors, who were the ultimate source of exploitation, and allowing exchange to happen on a “peer-to-peer” basis. By subverting the “monopoly” granted by copyright protections, radical change would happen on the basis of increased potential for voluntary market exchange, not political or social revolution.

Siva Vaidhyanathan’s Anarchist in the Library (2005) is a representative example of this argument, and made with explicit appeals to anarchist philosophy. According to Vaidhyanathan, “the new [peer-to-peer] technology evades the professional gatekeepers, flattening the production and distribution pyramid…. Digitization and networking have democratized the production of music” (48). This democratization by peer-to-peer distribution threatens “oligarchic forces such as global entertainment conglomerates” even as it works to “empower artists in new ways and connect communities of fans” (102).

The seeds of Digital Proudhonism were planted earlier than Napster, derived from the beliefs and practices of the Free Software movement. Threatened by intellectual property protections that signaled the corporatization of software development, the academics and amateurs of the Free Software movement developed alternative licenses that would keep software code “open” and thus able to share and build upon by any interested coder. This successfully protected the autonomous and collaborative working practices of the group. The movement’s major success was the Linux operating system, collaboratively built by a distributed team of mostly voluntary programmers who created a free alternative to the proprietary systems of Microsoft and Apple.

Linux indicated to those examining the front lines of technological development that, far from just a software development model, Free Software could actually be an alternative mode of production, and even a harbinger of democratic revolution. The triumph of an unpaid network-based community of programmers creating a free and open product in the face of the IP-dependent monopoly like Microsoft seemed to realize one of Marx’s ([1859] 1911) technologically determinist prophecies from A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—what is but a legal expression of the same thing—with the property relations within which they had been at work before. From forms of development of the forces of production these relations turn into their fetters. Then comes the era of social revolution. (12)

The Free Software movement provoked a wave of political initiatives and accompanying theorizations of a new digital economy based on what Yochai Benkler (2006) called “commons-based peer production.” With networked personal computers so widely distributed, “[t]he material requirements for effective information production and communication are now owned by numbers of individuals several orders of magnitude larger than the number of owners of the basic means of information production and exchange a mere two decades ago” (4). Suddenly, and almost as if by accident, the means of production were in the hands, not of corporations or states, but of individuals: a perfect encapsulation of the petty producer economy.

The classification of file sharing technologies such as Napster as “peer-to-peer” solidified this view. Napster’s design allowed users to exchange MP3 files by linking “peers” to one another, without storing files on Napster’s own servers. This performed two useful functions. It dispersed the server load for hosting and exchanging files among the computers and connections of Napster’s user base, alleviating what would have been massive bandwidth expenses. It also provided Napster with a defense against charges of infringement, as its own servers were not involved in copying files. This design might offer it protection from the charges that had doomed the site MP3.com, which had hosted user files.

While Napster’s suggestion that corporate structures for the distribution of culture could be supplanted by a voluntary federation of “peers” was important, it was ultimately a mystification. Not only did the courts find Napster liable for facilitating infringement, but the flat, “decentralized” topology of Napster still relied on the company’s central listing service to connect peers. Yet the ideological impact was profound. A law review article by Raymond Ku (2002), the then-director of the Institute of Law, Science & Technology, Seton Hall University School of Law is illustrative of both the nature of the arguments and how widespread and respectable they became in the post-Napster era: “the argument for copyright is primarily an argument for protecting content distributors in a world in which middlemen are obsolete. Copyright is no longer needed to encourage distribution because consumers themselves build and fund the distribution channels for digital content” (263). Clay Shirky’s (2008) paeans to “the mass amateurization of efforts previously reserved for media professionals” sound a similar note (55), presenting a technologically functionalist explanation for the existence of “gatekeeper” media industries: “It used to be hard to move words, images, and sounds from creator to consumer… The commercial viability of most media businesses involves providing those solutions, so preservation of the original problems became an economic imperative. Now, though, the problems of production, reproduction, and distribution are much less serious” (59). This narrative has remained persistent years after the brief flourishing of Napster: “the rise of peer-to-peer distribution systems… make middlemen hard to identify, if not cutting them out of the process altogether” (Kernfeld 2011, 217).

This situation was given an emancipatory political valence by intellectuals associated with copyright reform. Eager to protect an emerging sector of cultural production founded on sampling, remixing and file sharing, they described the accumulation of digital information and media online as a “commons,” which could be treated in an alternative way from forms of private property. Due to the lack of rivalry among digital goods (Benkler 2006, 36), users do not deplete the common stock, and so should benefit from a laxer approach to property rights. Law professor Lawrence Lessig (2004) started an initiative, Creative Commons, dedicated to establishing new licenses that would “build a layer of reasonable copyright on top of the extremes that now reign” (282). Part of Lessig’s argument for Creative Commons classifies media production and distribution, such as making music videos or mashups, as a “form of speech.” Therefore, copyright acted as unjust government regulation, and so must be resisted. “It is always a bad deal for the government to get into the business of regulating speech markets,” Lessig argues, even going so far as to raise the specter of communist authoritarianism: “It is the Soviet Union under Brezhnev” (128). Here Lessig performs a delicate rhetorical sleight of hand: the positioning cultural production as speech, it reifies a vision of such production as emanating from a solitary, individual producer who must remain unencumbered when bringing that speech to market.

Cory Doctorow (2014), a poster child of achievement in the new peer-to-peer world (in Free Culture, Lessig boasts of Doctorow’s successful promotional strategy of giving away electronic copies of his books for free), argues from a pro-market position against middlemen in his latest book: “copyright exists to protect middlemen, retailers, and distributors from being out-negotiated by creators and their investors” (48). While the argument remains the same, some targets have shifted: “investors” are “publishers, studios, record labels” while “intermediaries” are the platforms of distribution: “a distributor, a website like YouTube, a retailer, an e-commerce site like Amazon, a cinema owner, a cable operator, a TV station or network” (27).

While the thrust of these critiques of copyright focus on egregious overreach by the culture industries and their assault upon all manner of benign noncommercial activity, they also reveal a vision of an alternative cultural economy of independent producers who, while not necessarily anti-capitalist, can escape the clutches of massive centralized corporations through networked digital technologies. This facilitates both economic and political freedom via independence from control and regulation, and maximum opportunities on the market. “By giving artists the tools and technologies to take charge of their own production, marketing, and distribution, digitization underscored the disequilibrium of traditional record contracts and offered what for many is a preferable alternative” (Sinnreich 2013, 124). As it so often does, the fusion of ownership and labor characteristic of the petty producer standpoint, the structure of feeling of the independent artisan, articulates itself through the mantra of “Do It Yourself.”

These analyses and polemics reproduce the Proudhonist vision of an alternative to existing digital capitalism. Individual independent creators will achieve political autonomy and economic benefit through the embrace digital network technologies, as long as these creators are allowed to compete fairly with incumbents. Rather than insist on collective regulation of production, Digital Proudhonism seeks forms of deregulation, such as copyright reform, that will chip away at the existence of “monopoly” power of existing media corporations that fetters the market chances of these digital artisans.

Digital Proudhonism Today

Rooted in emergent digital methods of cultural production, the first wave of Digital Proudhonism shored up its petty producer standpoint through a rhetoric that centered the figure of the artist or “creator.” The contemporary term is the more expansive “the creative,” which lionizes a larger share of knowledge workers of the digital economy. As Sarah Brouillette (2009) notes, thinkers from management gurus such as Richard Florida to radical autonomist Marxist theorists such as Paolo Virno “broadly agree that over the past few decades more work has become comparable to artists’ work.” As a kind of practical consciousness, Digital Proudhonism easily spreads through the channels of the so-called “creative class,” its politics and worldview traveling under a host of other endeavors. These initiatives self-consciously seek to realize the ideals of Proudhonism in fields beyond the confines of music and film, with impact in manufacturing, social organization, and finance.

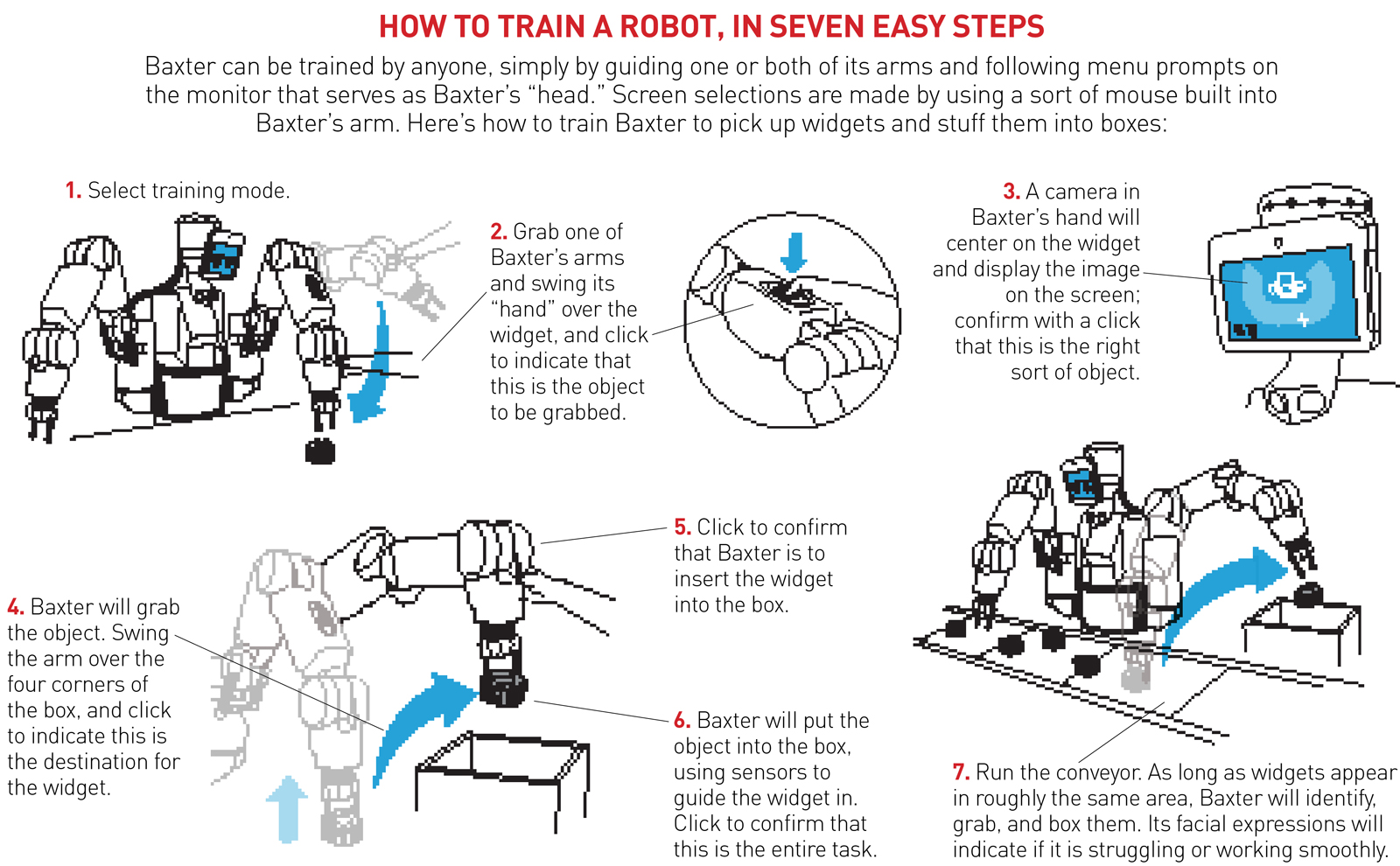

The maker movement is one prominent translation of Digital Proudhonism into a challenge to the contemporary organization of production, with allegedly radical effects on politics and economics. With the advent of new production technologies, such as 3D printers and digital design tools, “makers” can take the democratizing promise of the digital commons into the physical world. Just as digital technology supposedly distributes the means of production of culture across a wider segment of the population, so too will it spread manufacturing blueprints, blowing apart the restrictions of patents the same way Napster tore copyright asunder. “The process of making physical stuff has started to look more like the process of making digital stuff,” claims Chris Anderson (2012), author of Makers: The New Industrial Revolution (25). This has a radical effect: a realization of the goals of socialism via the unfolding of technology and the granting of access. “If Karl Marx were here today, his jaw would be on the floor. Talk about ‘controlling the tools of production’: you (you!) can now set factories into motion with a mouse click” (26). The key to this revolution is the ability of open-source methods to lower costs, thereby fusing the roles of inventor and entrepreneur (27).

Anderson’s “new industrial revolution” is one of a distinctly Proudhonian cast. Digital design tools are “extending manufacturing to a hugely expanded population of producers—the existing manufacturers plus a lot of regular folk who are becoming entrepreneurs” (41). The analogy to the rise of remix culture and amateur production lionized by Lessig is deliberate: “Sound familiar? It’s exactly what happened with the Web” (41). Anderson envisions the maker movement to be akin to the nineteenth century petty producers represented by Proudhon’s views: Cottage industries “were closer to what a Maker-driven New Industrial Revolution might be than are the big factories we normally associate with manufacturing” (49). Anderson’s preference for the small producer over the large factory echoes Proudhon. The subject of this revolution is not the proletarian at work in the large factory, but the artisan who owns their own tools.

A more explicitly radical perspective comes from the avowedly Proudhonist Center for a Stateless Society (C4SS), a “left market anarchist think tank and media center” deeply conversant in libertarian and so-called anarcho-capitalist economic theory. As with Anderson, C4SS subscribes to the techno-utopian potentials for a new arrangement of production driven by digital technology, which has the potential to reduce prices on goods, making them within the reach of anyone (once again, music piracy is held up as a precursor). However, this potential has not been realized because “economic ruling classes are able to enclose the increased efficiencies from new technology as a source of rents mainly through artificial scarcities, artificial property rights, and entry barriers enforced by the state” (Carson 2015a). Monopolies, enforced by the state, have “artificially” distorted free market transactions.

These monopolies, in the form of intellectual property rights, are preventing a proper Proudhonian revolution in which everyone would control their own individual production process. “The main source of continued corporate control of the production process is all those artificial property rights such as patents, trademarks, and business licenses, that give corporations a monopoly on the conditions under which the new technologies can be used” (Carson 2015a). However, once these artificial monopolies are removed, corporations will lose their power and we can have a world of “small neighborhood cooperative shops manufacturing for local barter-exchange networks in return for the output of other shops, of home microbakeries and microbreweries, surplus garden produce, babysitting and barbering, and the like” (Carson 2015a).

This revolution is a quiet one, requiring no strikes or other confrontations with capitalists. Instead, the answer is to create this new economy within the larger one, and hollow it out from the inside:

Seizing an old-style factory and holding it against the forces of the capitalist state is a lot harder than producing knockoffs in a garage factory serving the members of a neighborhood credit-clearing network, or manufacturing open-source spare parts to keep appliances running. As the scale of production shifts from dozens of giant factories owned by three or four manufacturing firms, to hundreds of thousands of independent neighborhood garage factories, patent law will become unenforceable. (Carson 2015b)

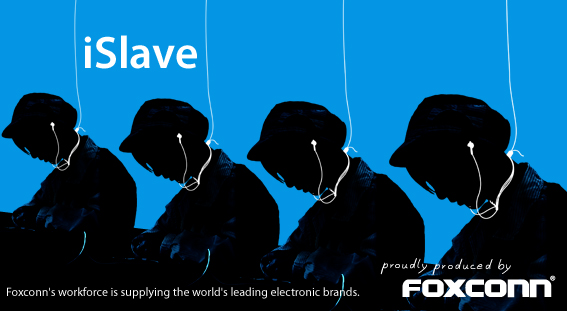

As Marx pointed out long ago, such petty producer fantasies of individually owned and operated manufacturing ironically rely upon the massive amounts of surplus generated from proletarians working in large-scale factories. The devices and infrastructures of the internet itself, as described by Nick Dyer-Witheford (2015) in his appropriately titled Cyber-Proletariat, are an obvious example. But proletarian labor also appears in the Digital Proudhonists’ own utopian fantasies. Anderson, describing the change in innovation wrought by the internet, describes how his grandfather’s invention of a sprinkler system would have gone differently. “When it came time to make more than a handful of his designs, he wouldn’t have begged some manufacturer to license his ideas, he would have done it himself. He would have uploaded his design files to companies that could make anything from tens to tens of thousands for him, even drop-shipping them directly to customers” (15). These “companies” of course are staffed by workers very different from “makers,” who work in facilities of mass production. Their labor is obscured by an influential ideology of artisans who believe themselves reliant on nothing but a personal computer and their own creativity.

A recent Guardian column by Paul Mason, anti-capitalist journalist and author of the techno-optimistic Postcapitalism serves as a further example. Mason (2016) argues, similarly to the C4SS, that intellectual property is the glue holding together massive corporations, and the key to their power over production. Simply by giving up on patents, as recommended by Anderson, Proudhonists will outflank capitalism on the market. His example is the “revolutionary” business model of the craft brewery chain BrewDog, who “open-sourced its recipe collection” by releasing the information publicly, unlike its larger corporate competitors. For Mason, this is an astonishing act of economic democracy: armed with BrewDog’s recipes, “All you would need to convert them from homebrew approximations to the actual stuff is a factory, a skilled workforce, some raw materials and a sheaf of legal certifications.” In other words, all that is needed to achieve postcapitalism is capitalism precisely as Marx described it.

The pirate fantasies of subverting monopolies extend beyond the initiatives of makers. The Digital Proudhonist belief in revolutionary change rooted in individual control of production and exchange on markets liberated from incumbents such as corporations and the state drives much of the innovation on the margins of tech. A recent treatise on the digital currency Bitcoin lauds Napster’s ability to “cut out the middlemen,” likening the currency to the file sharing technology (Kelly 2014, 11). “It is a quantum leap in the peer-to-peer network phenomenon. Bitcoin is to value transfer what Napster was to music” (33). Much like the advocates of digital currencies, Proudhon believed that state control of money was an unfair manipulation of the market, and sought to develop alternative currencies and banks rooted in labor-time, a belief that Marx criticized for its misunderstanding of the role of abstract labor in production.

In this way, Proudhon and his beliefs fit naturally into the dominant ideologies surrounding Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies: that economic problems stem from the conspiratorial manipulation of “fiat” currency by national governments and financial organizations such as the Federal Reserve. In light of recent analyses that suggest that Bitcoin functions less as a means of exchange than as a sociotechnical formation to which an array of faulty right-wing beliefs about economics adheres (Golumbia 2016), and the revelation that contemporary fascist groups rely on Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency to fund their activities (Ebner 2018), it is clear that Digital Proudhonism exists comfortably beside the most reactionary ideologies. Historically, this was true of Proudhon’s own work as well. As Zeev Sternhell (1996) describes, the early twentieth-century French political organization the Cercle Proudhon were captivated by Proudhon’s opposition to Marxism, his distaste for democracy, and his anti-Semitism. According to Sternhell, the group was an influential source of French proto-fascist thought.

Alternatives

The goal of this paper is not to question the creativity of remix culture or the maker movement, or to indict their potentials for artistic expression, or negate all their criticisms of intellectual property. What I wish to criticize is the outsized economic and political claims made about it. These claims have an impact on policy, such as Obama’s “Nation of Makers” initiative (The White House Office of the Press Secretary 2016), which draws upon numerous federal agencies, hundreds of schools, as well as educational product companies to spark “a renaissance of American manufacturing and hardware innovation.” But further, like Marx, I not only think Proudhonism rests on incorrect analyses of cultural labor, but that such ideas lead to bad politics. As Astra Taylor (2014) extensively documents in The People’s Platform, for all the exclamations of new opportunities with the end of middlemen and gatekeepers, the creative economy is as difficult as it ever was for artists to navigate, noting that writers like Lessig have replaced the critique of the commodification of culture with arguments about state and corporate control (26-7). Meanwhile, many of the fruits of this disintermediation have been plucked by an exploitative “sharing economy” whose platforms use “peer-to-peer” to subvert all manner of regulations; at least one commentator has invoked Napster’s storied ability to “cut out the middlemen” to describe AirBnB and Uber (Karabel 2014).

Digital Proudhonism and its vision of federations of independent individual producers and creators (perhaps now augmented with the latest cryptographic tools) dominates the imagination of a radical challenge to digital capitalism. Its critiques of the corporate internet have become common sense. What kind of alternative radical vision is possible? Here I believe it is useful to return to the core of Marx’s critique of Proudhon.

Marx saw that the unromantic labor of proletarians, combining varying levels of individual productivity within the factory through machines which themselves are the product of social labor, capitalism’s dynamics create a historically novel form of production—social production—along with new forms of culture and social relations. For Marx ([1867] 1992), this was potentially the basis for an economy beyond capitalism. To attempt to move “back” to individual production was reactionary: “As soon as the workers are turned into proletarians, and their means of labour into capital, as soon as the capitalist mode of production stands on its own feet, then the further socialization of labour and further transformation of the soil and other means of production into socially exploited and, therefore, communal means of production takes on a new form” (928).

The socialization of production under the development of the means of production—the necessity of greater collaboration and the reliance on past labors in the form of machines—gives way to a radical redefinition of the relationship to one’s output. No one can claim a product was made by them alone; rather, production demands to be recognized as social. Describing the socialization of labor through industrialization in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Engels ([1880] 2008) states, “The yarn, the cloth, the metal articles that now came out of the factory were the joint product of many workers, through whose hands they had successively to pass before they were ready. No one person could say of them: ‘I made that; this is my product’” (56). To put it in the language of cultural production, there can be no author. Or, in another implicit recognition that the work of today relies on the work of many others, past and present: everything is a remix.

Or instead of a remix, a “vortex,” to use the language of Nick Dyer-Witheford (2015), whose Cyber-Proletariat reminds us that the often-romanticized labor of digital creators and makers is but one stratum among many that makes up digital culture. The creative economy is a relatively privileged sector in an immense global “factory” made up of layers of formal and informal workers operating at the point of production, distribution and consumption, from tantalum mining to device manufacture to call center work to app development. The romance of “DIY” obscures the reality that nothing digital is done by oneself: it is always already a component of a larger formation of socialized labor.

The labor of digital creatives and innovators, sutured as it is to a technical apparatus fashioned from dead labor and meant for producing commodities for profit, is therefore already socialized. While some of this socialization is apparent in peer production, much of it is mystified through the real abstraction of commodity fetishism, which masks socialization under wage relations and contracts. Rather than further rely on these contracts to better benefit digital artisans, a Marxist politics of digital culture would begin from the fact of socialization, and as Radhika Desai (2011) argues, take seriously Marx’s call for “a general organization of labour in society” via political organizations such as unions and labor parties (212). Creative workers could align with others in the production chain as a class of laborers rather than as an assortment of individual producers, and form the kinds of organizations, such as unions, that have been the vehicles of class politics, with the aim of controlling society’s means of production, not simply one’s “own” tools or products. These would be bonds of solidarity, not bonds of market transactions. Then the apparatus of digital cultural production might be controlled democratically, rather than by the despotism of markets and private profit.

_____

Gavin Mueller Gavin Mueller holds a PhD in Cultural Studies from George Mason University. He teaches in the New Media and Digital Culture program at the University of Amsterdam.

_____

Notes

[1] The Pirate Bay, the largest and most antagonistic site of the peer-to-peer movement, has founders who identified as libertarian, socialist, and apolitical, respectively, and acquired funding from Carl Lundström, an entrepreneur associated with far-right movements (Schwartz 2014, 142).

_____

Works Cited

- Anderson, Chris. 2012. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business.

- Barbrook, Richard and Andy Cameron. 1996. “The Californian Ideology.” Science as Culture 6:1. 44-72.

- Barlow, John Perry. 1996. “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- Benkler, Yochai. 2006. The Wealth of Networks. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Boyle, James. 2008. Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Brouillette, Sarah. 2009. “Creative Labor.” Mediations: Journal of the Marxist Literary Group 24:2. 140-149.

- Carson, Kevin. 2015a. “Nothing to Fear from New Technologies if the Market is Free.” Center for a Stateless Society.

- Carson, Kevin. 2015b. “Paul Mason and His Critics (Such As They Are).” Center for a Stateless Society.

- Desai, Radhika. 2011. “The New Communists of the Commons: Twenty-First-Century Proudhonists.” International Critical Thought 1:2. 204-223.

- Doctorow, Cory. 2014. Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free: Laws for the Internet Age. San Francisco: McSweeney’s.

- Dyer-Witheford, Nick. 2015. Cyber-proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex. London: Pluto Press.

- Ebner, Julia, 2018. “The Currency of the Far-Right: Why Neo-Nazis Love Bitcoin.” The Guardian (Jan 24).

- Engels, Friedrich. (1880) 2008. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Trans. Edward Aveling. New York: Cosimo Books, 2008.

- Golumbia, David. 2016. The Politics of Bitcoin: Software as Right-Wing Extremism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Karabel, Zachary. 2014. “Requiem for the Middleman.” Slate (Apr 25).

- Kelly, Brian. 2014. The Bitcoin Big Bang: How Alternative Currencies Are About to Change the World. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Kernfeld, Barry. 2011. Pop Song Piracy: Disobedient Music Distribution Since 1929. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ku, Raymond Shih Ray. 2002. “The Creative Destruction of Copyright: Napster and the New Economics of Digital Technology.” The University of Chicago Law Review 69, no. 1: 263-324.

- Lessig, Lawrence. 2004. Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity. New York: Penguin Books.

- Lessig, Lawrence. 2008. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the New Economy. New York: Penguin.

- Marx, Karl. (1847) 1973. The Poverty of Philosophy. New York: International Publishers.

- Marx, Karl. (1859) 1911. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by N.I. Stone. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr and Co.

- Marx, Karl. (1865) 2016. “On Proudhon.” Marxists Internet Archive.

- Marx, Karl. (1867) 1992. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1. Trans. Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin Books.

- Mason, Paul. 2016, “BrewDog’s Open-Source Revolution is at the Vanguard of Postcapitalism.” The Guardian (Feb 29).

- McLeod, Kembrew. 2005. Freedom of Expression: Overzealous Copyright Bozos and Other Enemies of Creativity. New York: Doubleday.

- McNally, David. 1993. Against the Market: Political Economy, Market Socialism and the Marxist Critique. London: Verso.

- Murray, Patrick. 2016. The Mismeasure of Wealth: Essays on Marx and Social Form. Leiden: Brill.

- The White House Office of the Press Secretary. 2016. “New Commitments in Support of the President’s Nation of Makers Initiative to Kick Off 2016 National Week of Making.” June 17.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1840) 2011. “What is Property.” In Property is Theft! A Pierre-Joseph Proudhon Reader, edited by Iain McKay. Translated by Benjamin R. Tucker. Edinburgh: AK Press.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1847) 2012. The Philosophy of Poverty: The System of Economic Contradictions. Translated by Benjamin R. Tucker. Floating Press.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1851) 2003. General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century. Translated by John Beverly Robinson. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1863) 1979. The Principle of Federation. Translated by Richard Jordan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Schwartz, Jonas Andersson. 2014. Online File Sharing: Innovations in Media Consumption. New York: Routledge.

- Sinnreich, Aram. 2013. The Piracy Crusade: How the Music Industry’s War on Sharing Destroys Markets and Erodes Civil Liberties. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. New York: Penguin.

- Sternhell, Zeev. 1996. Neither Right Nor Left: Fascist Ideology in France. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taylor, Astra. 2014. The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in a Digital Age. New York: Metropolitan Books.

- Vaidhyanathan, Siva. 2005. The Anarchist in the Library: How the Clash Between Freedom and Control is Hacking the Real World and Crashing the System. New York: Basic Books.

- Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Winner, Langdon. 1997. “Cyberlibertarian Myths and The Prospects For Community.” Computers and Society 27:3. 14 – 19.

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)

a review of N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012)

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)