a review of Jeff Orlowski, dir., The Social Dilemma (Netflix/Exposure Labs/Argent Pictures, 2020)

by Zachary Loeb

~

The myth of technological and political and social inevitability is a powerful tranquilizer of the conscience. Its service is to remove responsibility from the shoulders of everyone who truly believes in it. But, in fact, there are actors!

– Joseph Weizenbaum (1976)

Why did you last look at your smartphone? Did you need to check the time? Was picking it up a conscious decision driven by the need to do something very particular, or were you just bored? Did you turn to your phone because its buzzing and ringing prompted you to pay attention to it? Regardless of the particular reasons, do you sometimes find yourself thinking that you are staring at your phone (or other computerized screens) more often than you truly want? And do you ever feel, even if you dare not speak this suspicion aloud, that your gadgets are manipulating you?

The good news is that you aren’t just being paranoid, your gadgets were designed in such a way as to keep you constantly engaging with them. The bad news is that you aren’t just being paranoid, your gadgets were designed in such a way as to keep you constantly engaging with them. What’s more, on the bad news front, these devices (and the platforms they run) are constantly sucking up information on you and are now pushing and prodding you down particular paths. Furthermore, alas more bad news, these gadgets and platforms are not only wreaking havoc on your attention span they are also undermining the stability of your society. Nevertheless, even though there is ample cause to worry, the new film The Social Dilemma ultimately has good news for you: a collection of former tech-insiders is starting to speak out! Sure, many of these individuals are the exact people responsible for building the platforms that are currently causing so much havoc—but they meant well, they’re very sorry, and (did you hear?) they meant well.

Directed by Jeff Orlowski, and released to Netflix in early September 2020, The Social Dilemma is a docudrama that claims to provide a unsparing portrait of what social media platforms have wrought. While the film is made up of a hodgepodge of elements, at the core of the work are a series of interviews with Silicon Valley alumni who are concerned with the direction in which their former companies are pushing the world. Most notable amongst these, the film’s central character to the extent it has one, is Tristan Harris (formerly a design ethicists at Google, and one of the cofounders of The Center for Humane Technology) who is not only repeatedly interviewed but is also shown testifying before the Senate and delivering a TED style address to a room filled with tech luminaries. This cast of remorseful insiders is bolstered by a smattering of academics, and non-profit leaders, who provide some additional context and theoretical heft to the insiders’ recollections. And beyond these interviews the film incorporates a fictional quasi-narrative element depicting the members of a family (particularly its three teenage children) as they navigate their Internet addled world—with this narrative providing the film an opportunity to strikingly dramatize how social media “works.”

The Social Dilemma makes some important points about the way that social media works, and the insiders interviewed in the film bring a noteworthy perspective. Yet beyond the sad eyes, disturbing animations, and ominous music The Social Dilemma is a piece of manipulative filmmaking on par with the social media platforms it critiques. While presenting itself as a clear-eyed expose of Silicon Valley, the film is ultimately a redemption tour for a gaggle of supposedly reformed techies wrapped in an account that is so desperate to appeal to “both sides” that it is unwilling to speak hard truths.

The film warns that the social media companies are not your friends, and that is certainly true, but The Social Dilemma is not your friend either.

The Social Dilemma

As the film begins the insiders introduce themselves, naming the companies where they had worked, and identifying some of the particular elements (such as the “like” button) with which they were involved. Their introductions are peppered with expressions of concern intermingled with earnest comments about how “Nobody, I deeply believe, ever intended any of these consequences,” and that “There’s no one bad guy.” As the film transitions to Tristan Harris rehearsing for the talk that will feature later in the film, he comments that “there’s a problem happening in the tech industry, and it doesn’t have a name.” After recounting his personal awakening, whilst working at Google, and his attempt to spark a serious debate about these issues with his coworkers, the film finds “a name” for the “problem” Harris had alluded to: “surveillance capitalism.” The thinker who coined that term, Shoshana Zuboff, appears to discuss this concept which captures the way in which Silicon Valley thrives not off of users’ labor but off of every detail that can be sucked up about those users and then sold off to advertisers.

After being named, “surveillance capitalism” hovers in the explanatory background as the film considers how social media companies constantly pursue three goals: engagement (to keep you coming back), growth (to get you to bring in more users), and advertising (to get better at putting the right ad in front of your eyes, which is how the platforms make money). The algorithms behind these platforms are constantly being tweaked through A/B testing, with every small improvement being focused around keeping users more engaged. Numerous problems emerge: designed to be addictive, these platforms and devices claw at users’ attention; teenagers (especially young ones) struggle as their sense of self-worth becomes tied to “likes;” misinformation spreads rapidly in an information ecosystem wherein the incendiary gets more attention than the true; and the slow processes of democracy struggle to keep up with the speed of technology. Though the concerns are grave, and the interviewees are clearly concerned, the tonality is still one of hopefulness; the problem here is not really social media, but “surveillance capitalism,” and if “surveillance capitalism” can be thwarted then the true potential of social media can be attained. And the people leading that charge against “surveillance capitalism”? Why, none other than the reformed insiders in the film.

While the bulk of the film consists of interviews, and news clips, the film is periodically interrupted by a narrative in which a family with three teenage children is shown. The Mother (Barbara Gehring) and Step-Father (Chris Grundy) are concerned with their children’s social media usage, even as they are glued to their own devices. As for the children: the oldest Cassandra (Kara Hayward) is presented as skeptical towards social media, the youngest Isla (Sophia Hammons) Is eager for online popularity, and the middle child Ben (Skyler Gisondo) eventually falls down the rabbit hole of recommended conspiratorial content. As the insiders, and academics, talk about the various dangers of social media the film shifts to the narrative to dramatize these moments – thus a discussion of social media’s impact on young teenagers, particularly girls, cuts to Isla being distraught after an insulting comment is added to one of the images she uploads. Cassandra (that name choice can’t be a coincidence) is presented as most in line with the general message of the film and the character refers to Jaron Lanier as a “genius” and in another sequence is shown reading Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Yet the member of the family the film dwells on the most is almost certainly Ben. For the purposes of dramatizing how an algorithm works, the film repeatedly returns to a creepy depiction of the Advertising, Engagement, and Growth Ais (all played by Vincent Kartheiser) as they scheme to get Ben to stay glued to his phone. Beyond the screens, the world in the narrative is being rocked by a strange protest movement calling itself “The Extreme Center” – whose argument seems to be that both sides can’t be trusted – and Ben eventually gets wrapped up in their message. The family’s narrative concludes with Ben and Cassandra getting arrested at a raucous rally held by “The Extreme Center,” sitting handcuffed on the ground and wondering how it is that this could have happened.

To the extent that The Social Dilemma builds towards a conclusion, it is the speech that Harris gives (before an audience that includes many of the other interviewees in the film). And in that speech, and the other comments made around it, the point that is emphasized is that Silicon Valley must get away from “surveillance capitalism.” It must embrace “humane technology” that seeks to empower users not entangle them. Emphasizing that, despite how things have turned out, that “I don’t think these guys set out to be evil” the various insiders double-down on their belief in high-tech’s liberatory potential. Contrasting rather unflattering imagery of Mark Zuckerberg (without genuinely calling him out) testifying with images of Steve Jobs in his iconic turtleneck, the film claims “the idea of humane technology, that’s where Silicon Valley got its start.” And before the credits roll, Harris seems to speak for his fellow insiders as he notes “we built these things, and we have a responsibility to change it.” For those who found the film unsettling, and who are confused by exactly what they are meant to do if they are not part of Harris’s “we,” the film offers some straightforward advice. Drawing on their own digital habits, the insiders recommend: turning off notifications, never watching a recommended video, opting for a less-invasive search engine, trying to escape your content bubble, keeping your devices out of your bedroom, and being a critical consumer of information.

It is a disturbing film, and it is constructed so as to unsettle the viewer, but it still ends on a hopeful note: reform is possible, and the people in this film are leading that charge. The problem is not social media as such, but what the ways in which “surveillance capitalism” has thwarted what social media could really be. If, after watching The Social Dilemma, you feel concerned about what “surveillance capitalism” has done to social media (and you feel prepared to make some tweaks in your social media use) but ultimately trust that Silicon Valley insiders are on the case—then the film has succeeded in its mission. After all, the film may be telling you to turn off Facebook notifications, but it doesn’t recommend deleting your account.

Yet one of the points the film makes is that you should not accept the information that social media presents to you at face value. And in the same spirit, you should not accept the comments made by oh-so-remorseful Silicon Valley insiders at face value either. To be absolutely clear: we should be concerned about the impacts of social media, we need to work to rein in the power of these tech companies, we need to be willing to have the difficult discussion about what kind of society we want to live in…but we should not believe that the people who got us into this mess—who lacked the foresight to see the possible downsides in what they were building—will get us out of this mess. If these insiders genuinely did not see the possible downsides of what they were building, than they are fools who should not be trusted. And if these insiders did see the possible downsides, continued building these things anyways, and are now pretending that they did not see the downsides, than they are liars who definitely should not be trusted.

It’s true, arsonists know a lot about setting fires, and a reformed arsonist might be able to give you some useful fire safety tips—but they are still arsonists.

There is much to be said about The Social Dilemma. Indeed, anyone who cares about these issues (unfortunately) needs to engage with The Social Dilemma if for no other reason than the fact that this film will be widely watched, and will thus set much of the ground on which these discussions take place. Therefore, it is important to dissect certain elements of the film. To be clear, there is a lot to explore in The Social Dilemma—a book or journal issue could easily be published in which the docudrama is cut into five minute segments with academics and activists being each assigned one segment to comment on. While there is not the space here to offer a frame by frame analysis of the entire film, there are nevertheless a few key segments in the film which deserve to be considered. Especially because these key moments capture many of the film’s larger problems.

“when bicycles showed up”

A moment in The Social Dilemma that perfectly, if unintentionally, sums up many of the major flaws with the film occurs when Tristan Harris opines on the history of bicycles. There are several problems in these comments, but taken together these lines provide you with almost everything you need to know about the film. As Harris puts it:

No one got upset when bicycles showed up. Right? Like, if everyone’s starting to go around on bicycles, no one said, ‘Oh, my God, we’ve just ruined society. [chuckles] Like, bicycles are affecting people. They’re pulling people away from their kids. They’re ruining the fabric of democracy. People can’t tell what’s true.’ Like we never said any of that stuff about a bicycle.

Here’s the problem, Harris’s comments about bicycles are wrong.

They are simply historically inaccurate. Some basic research into the history of bicycles that looks at the ways that people reacted when they were introduced would reveal that many people were in fact quite “upset when bicycles showed up.” People absolutely were concerned that bicycles were “affecting people,” and there were certainly some who were anxious about what these new technologies meant for “the fabric of democracy.” Granted, that there were such adverse reactions to the introduction of bicycles should not be seen as particularly surprising, because even a fairly surface-level reading of the history of technology reveals that when new technologies are introduced they tend to be met not only with excitement, but also with dread.

Yet, what makes Harris’s point so interesting is not just that he is wrong, but that he is so confident while being so wrong. Smiling before the camera, in what is obviously supposed to be a humorous moment, Harris makes a point about bicycles that is surely one that will stick with many viewers—and what he is really revealing is that he needs to take some history classes (or at least do some reading). It is genuinely rather remarkable that this sequence made it into the final cut of the film. This was clearly an expensive production, but they couldn’t have hired a graduate student to watch the film and point out “hey, you should really cut this part about bicycles, it’s wrong”? It is hard to put much stock in Harris, and friends, as emissaries of technological truth when they can’t be bothered to do basic research.

That Harris speaks so assuredly about something which he is so wrong about gets at one of the central problems with the reformed insiders of The Social Dilemma. Though these are clearly intelligent people (lots of emphasis is placed on the fancy schools they attended), they know considerably less than they would like the viewers to believe. Of course, one of the ways that they get around this is by confidently pretending they know what they’re talking about, which manifests itself by making grandiose claims about things like bicycles that just don’t hold up. The point is not to mock Harris for this mistake (though it really is extraordinary that the segment did not get cut), but to make the following point: if Harris, and his friends, had known a bit more about the history of technology, and perhaps if they had a bit more humility about what they don’t know, perhaps they would not have gotten all of us into this mess.

A point that is made by many of the former insiders interviewed for the film is that they didn’t know what the impacts would be. Over and over again we hear some variation of “we meant well” or “we really thought we were doing something great.” It is easy to take such comments as expressions of remorse, but it is more important to see such comments as confessions of that dangerous mixture of hubris and historical/social ignorance that is so common in Silicon Valley. Or, to put it slightly differently, these insiders really needed to take some more courses in the humanities. You know how you could have known that technologies often have unforeseen consequences? Study the history of technology. You know how you could have known that new media technologies have jarring political implications? Read some scholarship from media studies. A point that comes up over and over again in such scholarly work, particularly works that focus on the American context, is that optimism and enthusiasm for new technology often keeps people (including inventors) from seeing the fairly obvious risks—and all of these woebegone insiders could have known that…if they had only been willing to do the reading. Alas, as anyone who has spent time in a classroom knows, a time honored way of covering up for the fact that you haven’t done the reading is just to speak very confidently and hope that your confidence will successfully distract from the fact that you didn’t do the reading.

It would be an exaggeration to claim “all of these problems could have been prevented if these people had just studied history!” And yet, these insiders (and society at large) would likely be better able to make sense of these various technological problems if more people had an understanding of that history. At the very least, such historical knowledge can provide warnings about how societies often struggle to adjust to new technologies, can teach how technological progress and social progress are not synonymous, can demonstrate how technologies have a nasty habit of biting back, and can make clear the many ways in which the initial liberatory hopes that are attached to a technology tend to fade as it becomes clear that the new technology has largely reinscribed a fairly conservative status quo.

At the very least, knowing a bit more about the history of technology can keep you from embarrassing yourself by confidently making claiming that “we never said any of that stuff about a bicycle.”

“to destabilize”

While The Social Dilemma expresses concern over how digital technologies impact a person’s body, the film is even more concerned about the way these technologies impact the body politic. A worry that is captured by Harris’s comment that:

We in the tech industry have created the tools to destabilize and erode the fabric of society.

That’s quite the damning claim, even if it is one of the claims in the film that probably isn’t all that controversial these days. Though many of the insiders in the film pine nostalgically for those idyllic days from ten years ago when much of the media and the public looked so warmly towards Silicon Valley, this film is being released at a moment when much of that enthusiasm has soured. One of the odd things about The Social Dilemma is that politics are simultaneously all over the film, and yet politics in the film are very slippery. When the film warns of looming authoritarianism: Bolsanaro gets some screen time, Putin gets some ominous screen time—but though Trump looms in the background of the film he’s pretty much unseen and unnamed. And when US politicians do make appearances we get Marco Rubio and Jeff Flake talking about how people have become too polarized and Jon Tester reacting with discomfort to Harris’s testimony. Of course, in the clip that is shown, Rubio speaks some pleasant platitudes about the virtues of coming together…but what does his voting record look like?

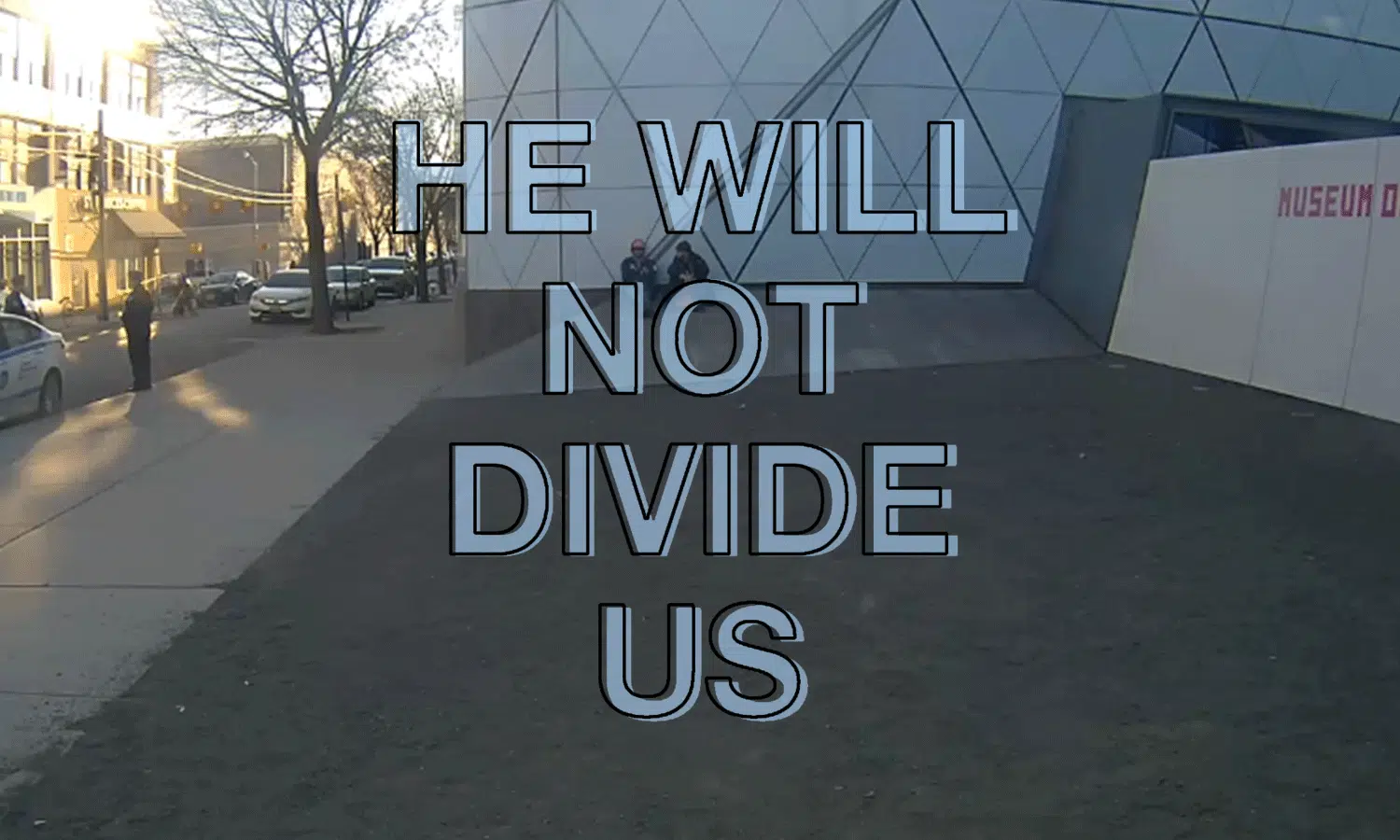

The treatment of politics in The Social Dilemma comes across most clearly in the narrative segment, wherein much attention is paid to a group that calls itself “The Extreme Center.” Though the ideology of this group is never made quite clear, it seems to be a conspiratorial group that takes as its position that “both sides are corrupt” – rejecting left and right it therefore places itself in “the extreme center.” It is into this group, and the political rabbit hole of its content, that Ben falls in the narrative – and the raucous rally (that ends in arrests) in the narrative segment is one put on by the “extreme center.” It may appear that “the extreme center” is just a simple storytelling technique, but more than anything else it feels like the creation of this fictional protest movement is really just a way for the film to get around actually having to deal with real world politics.

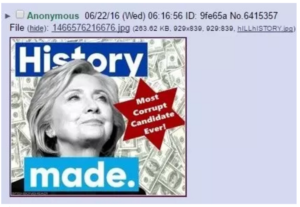

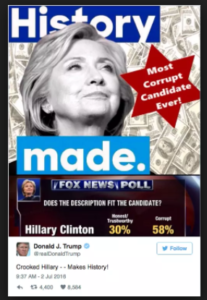

The film includes clips from a number of protests (though it does not bother to explain who these people are and why they are protesting), and there are some moments when various people can be heard specifically criticizing Democrats or Republicans. But even as the film warns of “the rabbit hole” it doesn’t really spend much time on examples. Heck, the first time that the words “surveillance capitalism” get spoken in the film are in a clip of Tucker Carlson. Some points are made about “pizzagate” but the documentary avoids commenting on the rapidly spreading QAnon conspiracy theory. And to the extent that any specific conspiracy receives significant attention it is the “flat earth” conspiracy. Granted, it’s pretty easy to deride the flat earthers, and in focusing on them the film makes a very conscious decision to not focus on white supremacist content and QAnon. Ben falls down the “extreme center” rabbit hole, and it may well be that the reason why the filmmakers have him fall down this fictional rabbit hole is so that they don’t have to talk about the likelihood that (in the real world) he would likely fall down a far-right rabbit hole. But The Social Dilemma doesn’t want to make that point, after all, in the political vision it puts forth the problem is that there is too much polarization and extremism on both sides.

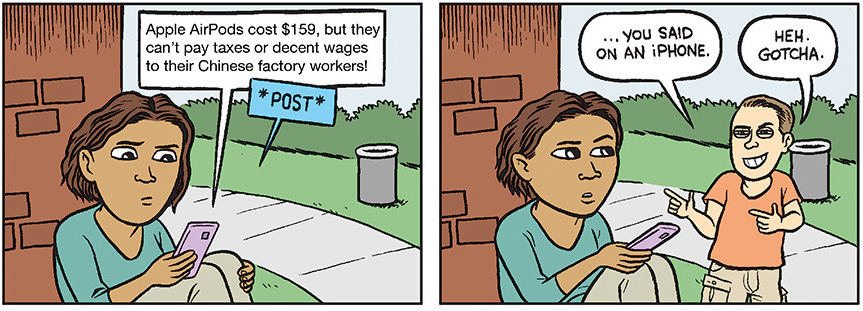

The Social Dilemma clearly wants to avoid taking sides. And in so doing demonstrates the ways in which Silicon Valley has taken sides. After all, to focus so heavily on polarization and the extremism of “both sides” just serves to create a false equivalency where none exists. But, the view that “the Trump administration has mismanaged the pandemic” and the view that “the pandemic is a hoax” – are not equivalent. The view that “climate change is real” and “climate change is a hoax” – are not equivalent. People organizing for racial justice and people organizing because they believe that Democrats are satanic cannibal pedophiles – are not equivalent. The view that “there is too much money in politics” and the view that “the Jews are pulling the strings” – are not equivalent. Of course, to say that these things “are not equivalent” is to make a political judgment, but by refusing to make such a judgment The Social Dilemma presents both sides as being equivalent. There are people online who are organizing for the cause of racial justice, and there are white-supremacists organizing online who are trying to start a race war—those causes may look the same to an algorithm, and they may look the same to the people who created those algorithms, but they are not the same.

You cannot address the fact that Facebook and YouTube have become hubs of violent xenophobic conspiratorial content unless you are willing to recognize that Facebook and YouTube actively push violent xenophobic conspiratorial content.

It is certainly true that there are activist movements from the left and the right organizing online at the moment, but when you watch a movie trailer on YouTube the next recommended video isn’t going to be a talk by Angela Davis.

“it’s the critics”

Much of the content of The Social Dilemma is unsettling, and the film makes it clear that change is necessary. Nevertheless, the film ends on a positive note. Pivoting away from gloominess, the film shows the rapt audience nodding as Harris speaks of the need for “humane technology,” and this assembled cast of reformed insiders is presented as proof that Silicon Valley is waking up to the need to take responsibility. Near the film’s end, Jaron Lanier hopefully comments that:

it’s the critics that drive improvement. It’s the critics who are the true optimists.

Thus, the sense that is conveyed at the film’s close is that despite the various worries that had been expressed—the critics are working on it, and the critics are feeling good.

But, who are the critics?

The people interviewed in the film, obviously.

And that is precisely the problem. “Critic” is something of a challenging term to wrestle with as it doesn’t necessarily take much to be able to call yourself, or someone else, a critic. Thus, the various insiders who are interviewed in the film can all be held up as “critics” and can all claim to be “critics” thanks to the simple fact that they’re willing to say some critical things about Silicon Valley and social media. But what is the real content of the criticisms being made? Some critics are going to be more critical than others, so how critical are these critics? Not very.

The Social Dilemma is a redemption tour that allows a bunch of remorseful Silicon Valley insiders to rebrand themselves as critics. Based on the information provided in the film it seems fairly obvious that a lot of these individuals are responsible for causing a great deal of suffering and destruction, but the film does not argue that these men (and they are almost entirely men) should be held accountable for their deeds. The insiders have harsh things to say about algorithms, they too have been buffeted about by nonstop nudging, they are also concerned about the rabbit hole, they are outraged at how “surveillance capitalism” has warped technological possibilities—but remember, they meant well, and they are very sorry.

One of the fascinating things about The Social Dilemma is that in one scene a person will proudly note that they are responsible for creating a certain thing, and then in the next scene they will say that nobody is really to blame for that thing. Certainly not them, they thought they were making something great! The insiders simultaneously want to enjoy the cultural clout and authority that comes from being the one who created the like button, while also wanting to escape any accountability for being the person who created the like button. They are willing to be critical of Silicon Valley, they are willing to be critical of the tools they created, but when it comes to their own culpability they are desperate to hide behind a shield of “I meant well.” The insiders do a good job of saying remorseful words, and the camera catches them looking appropriately pensive, but it’s no surprise that these “critics” should feel optimistic, they’ve made fortunes utterly screwing up society, and they’ve done such a great job of getting away with it that now they’re getting to elevate themselves once again by rebranding themselves as “critics.”

To be a critic of technology, to be a social critic more broadly, is rarely a particularly enjoyable or a particularly profitable undertaking. Most of the time, if you say anything critical about technology you are mocked as a Luddite, laughed at as a “prophet of doom,” derided as a technophobe, accused of wanting everybody to go live in caves, and banished from the public discourse. That is the history of many of the twentieth century’s notable social critics who raised the alarm about the dangers of computers decades before most of the insiders in The Social Dilemma were born. Indeed, if you’re looking for a thorough retort to The Social Dilemma you cannot really do better than reading Joseph Weizenbaum’s Computer Power and Human Reason—a book which came out in 1976. That a film like The Social Dilemma is being made may be a testament to some shifting attitudes towards certain types of technology, but it was not that long ago that if you dared suggest that Facebook was a problem you were denounced as an enemy of progress.

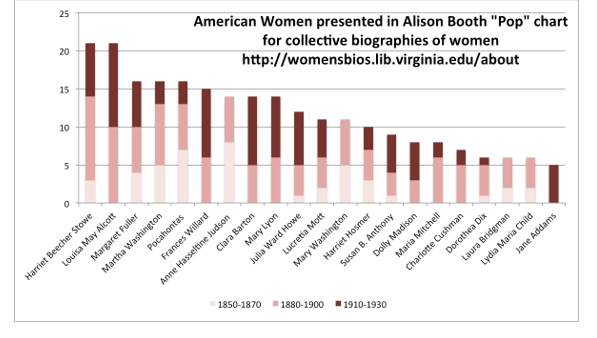

There are many phenomenal critics speaking out about technology these days. To name only a few: Safiya Noble has written at length about the ways that the algorithms built by companies like Google and Facebook reinforce racism and sexism; Virginia Eubanks has exposed the ways in which high-tech tools of surveillance and control are first deployed against society’s most vulnerable members; Wendy Hui Kyong Chun has explored how our usage of social media becomes habitual; Jen Schradie has shown the ways in which, despite the hype to the contrary, online activism tends to favor right-wing activists and causes; Sarah Roberts has pulled back the screen on content moderation to show how much of the work supposedly being done by AI is really being done by overworked and under-supported laborers; Ruha Benjamin has made clear the ways in which discriminatory designs get embedded in and reified by technical systems; Christina Dunbar-Hester has investigated the ways in which communities oriented around technology fail to overcome issues of inequality; Sasha Costanza-Chock has highlighted the need for an approach to design that treats challenging structural inequalities as the core objective, not an afterthought; Morgan Ames expounds upon the “charisma” that develops around certain technologies; and Meredith Broussard has brilliantly inveighed against the sort of “technochauvinist” thinking—the belief that technology is the solution to every problem—that is so clearly visible in The Social Dilemma. To be clear, this list of critics is far from all-inclusive. There are numerous other scholars who certainly could have had their names added here, and there are many past critics who deserve to be named for their disturbing prescience.

But you won’t hear from any of those contemporary critics in The Social Dilemma. Instead, viewers of the documentary are provided with a steady set of mostly male, mostly white, reformed insiders who were unable to predict that the high-tech toys they built might wind up having negative implications.

It is not only that The Social Dilemma ignores most of the figures who truly deserve to be seen as critics, but that by doing so what The Social Dilemma does is set the boundaries for who gets to be a critic and what that criticism can look like. The world of criticism that The Social Dilemma sets up is one wherein a person achieves legitimacy as a critic of technology as a result of having once been a tech insider. Thus what the film does is lay out, and then set about policing the borders of, what can pass for acceptable criticism of technology. This not only limits the cast of critics to a narrow slice of mostly white mostly male insiders, it also limits what can be put forth as a solution. You can rest assured that the former insiders are not going to advocate for a response that would involve holding the people who build these tools accountable for what they’ve created. On the one hand it’s remarkable that no one in the film really goes after Mark Zuckerberg, but many of these insiders can’t go after Zuckerberg—because any vitriol they direct at him could just as easily be directed at them as well.

It matters who gets to be deemed a legitimate critic. When news networks are looking to have a critic on it matters whether they call Tristan Harris or one of the previously mentioned thinkers, when Facebook does something else horrendous it matters whether a newspaper seeks out someone whose own self-image is bound up in the idea that the company means well or someone who is willing to say that Facebook is itself the problem. When there are dangerous fires blazing everywhere it matters whether the voices that get heard are apologetic arsonists or firefighters.

Near the film’s end, while the credits play, as Jaron Lanier speaks of Silicon Valley he notes “I don’t hate them. I don’t wanna do any harm to Google or Facebook. I just want to reform them so they don’t destroy the world. You know?” And these comments capture the core ideology of The Social Dilemma, that Google and Facebook can be reformed, and that the people who can reform them are the people who built them.

But considering all of the tangible harm that Google and Facebook have done, it is far past time to say that it isn’t enough to “reform” them. We need to stop them.

Conclusion: On “Humane Technology”

The Social Dilemma is an easy film to criticize. After all, it’s a highly manipulative piece of film making, filled with overly simplified claims, historical inaccuracies, conviction lacking politics, and a cast of remorseful insiders who still believe Silicon Valley’s basic mythology. The film is designed to scare you, but it then works to direct that fear into a few banal personal lifestyle tweaks, while convincing you that Silicon Valley really does mean well. It is important to view The Social Dilemma not as a genuine warning, or as a push for a genuine solution, but as part of a desperate move by Silicon Valley to rehabilitate itself so that any push for reform and regulation can be captured and defanged by “critics” of its own choosing.

Yet, it is too simple (even if it is accurate) to portray The Social Dilemma as an attempt by Silicon Valley to control both the sale of flamethrowers and fire extinguishers. Because such a focus keeps our attention pinned to Silicon Valley. It is easy to criticize Silicon Valley, and Silicon Valley definitely needs to be criticized—but the bright-eyed faith in high-tech gadgets and platforms that these reformed insiders still cling to is not shared only by them. The people in this film blame “surveillance capitalism” for warping the liberatory potential of Internet connected technologies, and many people would respond to this by pushing back on Zuboff’s neologism to point out that “surveillance capitalism” is really just “capitalism” and that therefore the problem is really that capitalism is warping the liberatory potential of Internet connected technologies. Yes, we certainly need to have a conversation about what to do with Facebook and Google (dismantle them). But at a certain point we also need to recognize that the problem is deeper than Facebook and Google, at a certain point we need to be willlng to talk about computers.

The question that occupied many past critics of technology was the matter of what kinds of technology do we really need? And they were clear that this was a question that was far too important to be left to machine-worshippers.

The Social Dilemma responds to the question of “what kind of technology do we really need?” by saying “humane technology.” After all, the organization The Center for Humane Technology is at the core of the film, and Harris speaks repeatedly of “humane technology.” At the surface level it is hard to imagine anyone saying that they disapprove of the idea of “humane technology,” but what the film means by this (and what the organization means by this) is fairly vacuous. When the Center for Humane Technology launched in 2018, to a decent amount of praise and fanfare, it was clear from the outset that its goal had more to do with rehabilitating Silicon Valley’s image than truly pushing for a significant shift in technological forms. Insofar as “humane technology” means anything, it stands for platforms and devices that are designed to be a little less intrusive, that are designed to try to help you be your best self (whatever that means), that try to inform you instead of misinform you, and that make it so that you can think nice thoughts about the people who designed these products. The purpose of “humane technology” isn’t to stop you from being “the product,” it’s to make sure that you’re a happy product. “Humane technology” isn’t about deleting Facebook, it’s about renewing your faith in Facebook so that you keep clicking on the “like” button. And, of course, “humane technology” doesn’t seem to be particularly concerned with all of the inhumanity that goes into making these gadgets possible (from mining, to conditions in assembly plants, to e-waste). “Humane technology” isn’t about getting Ben or Isla off their phones, it’s about making them feel happy when they click on them instead of anxious. In a world of empowered arsonists, “humane technology” seeks to give everyone a pair of asbestos socks.

Many past critics also argued that what was needed was to place a new word before technology – they argued for “democratic” technologies, or “holistic” technologies, or “convivial” technologies, or “appropriate” technologies, and this list could go on. Yet at the core of those critiques was not an attempt to salvage the status quo but a recognition that what was necessary in order to obtain a different sort of technology was to have a different sort of society. Or, to put it another way, the matter at hand is not to ask “what kind of computers do we want?” but to ask “what kind of society do we want?” and to then have the bravery to ask how (or if) computers really fit into that world—and if they do fit, how ubiquitous they will be, and who will be responsible for the mining/assembling/disposing that are part of those devices’ lifecycles. Certainly, these are not easy questions to ask, and they are not pleasant questions to mull over, which is why it is so tempting to just trust that the Center for Humane Technology will fix everything, or to just say that the problem is Silicon Valley.

Thus as the film ends we are left squirming unhappily as Netflix (which has, of course, noted the fact that we watched The Social Dilemma) asks us to give the film a thumbs up or a thumbs down – before it begins auto-playing something else.

The Social Dilemma is right in at least one regard, we are facing a social dilemma. But as far as the film is concerned, your role in resolving this dilemma is to sit patiently on the couch and stare at the screen until a remorseful tech insider tells you what to do.

_____

Zachary Loeb earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, an MA from the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU, and is currently a PhD candidate in the History and Sociology of Science department at the University of Pennsylvania. Loeb works at the intersection of the history of technology and disaster studies, and his research focusses on the ways that complex technological systems amplify risk, as well as the history of technological doom-saying. He is working on a dissertation on Y2K. Loeb writes at the blog Librarianshipwreck, and is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

_____

Works Cited

- Weizenbaum, Joseph. 1976. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. New York: WH Freeman & Co.

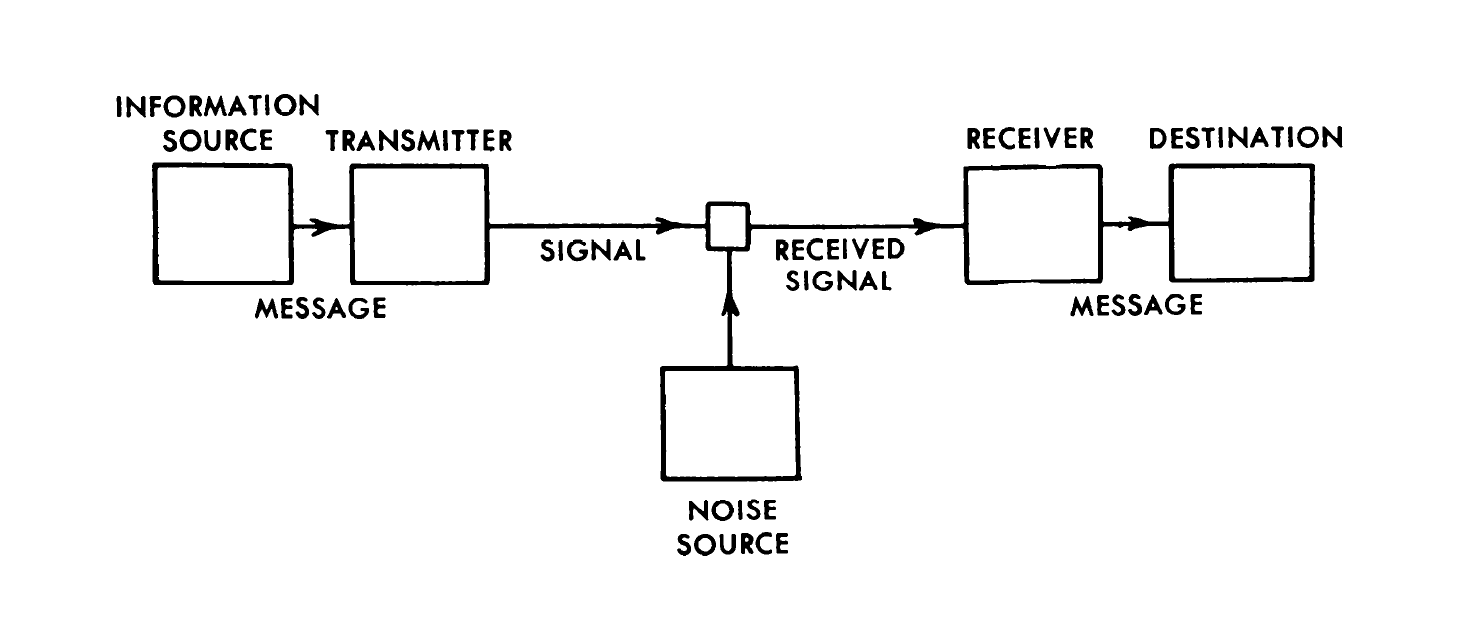

Shannon’s achievement was a general formula for the relation between the structure of the source and the noise in the channel.

Shannon’s achievement was a general formula for the relation between the structure of the source and the noise in the channel.