a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

by Zachary Loeb

~

Despite the aura of ethereality that clings to the Internet, today’s technologies have not shed their material aspects. Digging into the materiality of such devices does much to trouble the adoring declarations of “The Internet Is the Answer.” What is unearthed by digging is the ecological and human destruction involved in the creation of the devices on which the Internet depends—a destruction that Jussi Parikka considers an obscenity at the core of contemporary media.

Parikka’s tale begins deep below the Earth’s surface in deposits of a host of different minerals that are integral to the variety of devices without which you could not be reading these words on a screen. This story encompasses the labor conditions in which these minerals are extracted and eventually turned into finished devices, it tells of satellites, undersea cables, massive server farms, and it includes a dark premonition of the return to the Earth which will occur following the death (possibly a premature death due to planned obsolescence) of the screen at which you are currently looking.

In a connected duo of new books, The Anthrobscene (referenced below as A) and A Geology of Media (referenced below as GM), media scholar Parikka wrestles with the materiality of the digital. Parikka examines the pathways by which planetary elements become technology, while considering the transformations entailed in the anthropocene, and artistic attempts to render all of this understandable. Drawing upon thinkers ranging from Lewis Mumford to Donna Haraway and from the Situationists to Siegfried Zielinski – Parikka constructs a way of approaching media that emphasizes that it is born of the Earth, borne upon the Earth, and fated eventually to return to its place of origin. Parikka’s work demands that materiality be taken seriously not only by those who study media but also by all of those who interact with media – it is a demand that the anthropocene must be made visible.

Time is an important character in both The Anthrobscene and A Geology of Media for it provides the context in which one can understand the long history of the planet as well as the scale of the years required for media to truly decompose. Parikka argues that materiality needs to be considered beyond a simple focus upon machines and infrastructure, but instead should take into account “the idea of the earth, light, air, and time as media” (GM 3). Geology is harnessed as a method of ripping open the black box of technology and analyzing what the components inside are made of – copper, lithium, coltan, and so forth. The engagement with geological materiality is key for understanding the environmental implications of media, both in terms of the technologies currently in circulation and in terms of predicting the devices that will emerge in the coming years. Too often the planet is given short shrift in considerations of the technical, but “it is the earth that provides for media and enables it”, it is “the affordances of its geophysical reality that make technical media happen” (GM 13). Drawing upon Mumford’s writings about “paleotechnics” and “neotechnics” (concepts which Mumford had himself adapted from the work of Patrick Geddes), Parikka emphasizes that both the age of coal (paleotechnics) and the age of electricity (neotechnics) are “grounded in the wider mobilization of the materiality of the earth” (GM 15). Indeed, electric power is often still quite reliant upon the extraction and burning of coal.

More than just a pithy neologism, Parikka introduces the term “anthrobscene” to highlight the ecological violence inherent in “the massive changes human practices, technologies, and existence have brought across the ecological board” (GM 16-17) shifts that often go under the more morally vague title of “the anthropocene.” For Parikka, “the addition of the obscene is self-explanatory when one starts to consider the unsustainable, politically dubious, and ethically suspicious practices that maintain technological culture and its corporate networks” (A 6). Like a curse word beeped out by television censors, much of the obscenity of the anthropocene goes unheard even as governments and corporations compete with ever greater élan for the privilege of pillaging portions of the planet – Parikka seeks to reinscribe the obscenity.

The world of high tech media still relies upon the extraction of metals from the earth and, as Parikka shows, a significant portion of the minerals mined today are destined to become part of media technologies. Therefore, in contemplating geology and media it can be fruitful to approach media using Zielinski’s notion of “deep time” wherein “durations become a theoretical strategy of resistance against the linear progress myths that impose a limited context for understanding technological change” (GM 37, A 23). Deploying the notion of “deep time” demonstrates the ways in which a “metallic materiality links the earth to the media technological” while also emphasizing the temporality “linked to the nonhuman earth times of decay and renewal” (GM 44, A 30). Thus, the concept of “deep time” can be particularly useful in thinking through the nonhuman scales of time involved in media, such as the centuries required for e-waste to decompose.

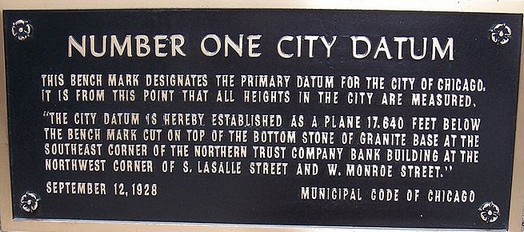

Whereas “deep time” provides insight into media’s temporal quality, “psychogeophysics” presents a method for thinking through the spatial. “Psychogeophysics” is a variation of the Situationist idea of “the psychogeographical,” but where the Situationists focused upon the exploration of the urban environment, “psychogeophysics” (which appeared as a concept in a manifesto in Mute magazine) moves beyond the urban sphere to contemplate the oblate spheroid that is the planet. What the “geophysical twist brings is a stronger nonhuman element that is nonetheless aware of the current forms of exploitation but takes a strategic point of view on the nonorganic too” (GM 64). Whereas an emphasis on the urban winds up privileging the world built by humans, the shift brought by “psychogeophysics” allows people to bear witness to “a cartography of architecture of the technological that is embedded in the geophysical” (GM 79).

The material aspects of media technology consist of many areas where visibility has broken down. In many cases this is suggestive of an almost willful disregard (ignoring exploitative mining and labor conditions as well as the harm caused by e-waste), but in still other cases it is reflective of the minute scales that materiality can assume (such as metallic dust that dangerously fills workers’ lungs after they shine iPad cases). The devices that are surrounded by an optimistic aura in some nations, thus obtain this sheen at the literal expense of others: “the residue of the utopian promise is registered in the soft tissue of a globally distributed cheap labor force” (GM 89). Indeed, those who fawn with religious adoration over the newest high-tech gizmo may simply be demonstrating that nobody they know personally will be sickened in assembling it, or be poisoned by it when it becomes e-waste. An emphasis on geology and materiality, as Parikka demonstrates, shows that the era of digital capitalism contains many echoes of the exploitation characteristic of bygone periods – appropriation of resources, despoiling of the environment, mistreatment of workers, exportation of waste, these tragedies have never ceased.

Digital media is excellent at creating a futuristic veneer of “smart” devices and immaterial sounding aspects such as “the cloud,” and yet a material analysis demonstrates the validity of the old adage “the more things change the more they stay the same.” Despite efforts to “green” digital technology, “computer culture never really left the fossil (fuel) age anyway” (GM 111). But beyond relying on fossil fuels for energy, these devices can themselves be considered as fossils-to-be as they go to rest in dumps wherein they slowly degrade, so that “we can now ask what sort of fossil layer is defined by the technical media condition…our future fossils layers are piling up slowly but steadily as an emblem of an apocalypse in slow motion” (GM 119). We may not be surrounded by dinosaurs and trilobites, but the digital media that we encounter are tomorrow’s fossils – which may be quite mysterious and confounding to those who, thousands of years hence, dig them up. Businesses that make and sell digital media thrive on a sense of time that consists of planned obsolescence, regular updates, and new products, but to take responsibility for the materiality of these devices requires that “notions of temporality must escape any human-obsessed vocabulary and enter into a closer proximity with the fossil” (GM 135). It requires a woebegone recognition that our technological detritus may be present on the planet long after humanity has vanished.

The living dead that lurch alongside humanity today are not the zombies of popular entertainment, but the undead media devices that provide the screens for consuming such distractions. Already fossils, bound to be disposed of long before they stop working, it is vital “to be able to remember that media never dies, but remains as toxic residue,” and thus “we should be able to repurpose and reuse solutions in new ways, as circuit bending and hardware hacking practices imply” (A 41). We live with these zombies, we live among them, and even when we attempt to pack them off to unseen graveyards they survive under the surface. A Geology of Media is thus “a call for further materialization of media not only as media but as that bit which it consists of: the list of the geophysical elements that give us digital culture” (GM 139).

It is not simply that “machines themselves contain a planet” (GM 139) but that the very materiality of the planet is becoming riddled with a layer of fossilized machines.

* * *

The image of the world conjured up by Parikka in A Geology of Media and The Anthrobscene is far from comforting – after all, Parikka’s preference for talking about “the anthrobscene” does much to set a funereal tone. Nevertheless, these two books by Parikka do much to demonstrate that “obscene” may be a very fair word to use when discussing today’s digital media. By emphasizing the materiality of media, Parikka avoids the thorny discussions of the benefits and shortfalls of various platforms to instead pose a more challenging ethical puzzle: even if a given social media platform can be used for ethical ends, to what extent is this irrevocably tainted by the materiality of the device used to access these platforms? It is a dark assessment which Parikka describes without much in the way of optimistic varnish, as he describes the anthropocene (on the first page of The Anthrobscene) as “a concept that also marks the various violations of environmental and human life in corporate practices and technological culture that are ensuring that there won’t be much of humans in the future scene of life” (A 1).

And yet both books manage to avoid the pitfall of simply coming across as wallowing in doom. Parikka is not pining for a primal pastoral fantasy, but is instead seeking to provide new theoretical tools with which his readers can attempt to think through the materiality of media. Here, Parikka’s emphasis on the way that digital technology is still heavily reliant upon mining and fossil fuels acts as an important counter to gee-whiz futurism. Similarly Parikka’s mobilization of the notion of “deep time” and fossils acts as an important contribution to thinking through the lifecycles of digital media. Dwelling on the undeath of a smartphone slowly decaying in an e-waste dump over centuries is less about evoking a fearful horror than it is about making clear the horribleness of technological waste. The discussion of “deep time” seems like it can function as a sort of geological brake on accelerationist thinking, by emphasizing that no matter how fast humans go, the planet has its own sense of temporality. Throughout these two slim books, Parikka draws upon a variety of cultural works to strengthen his argument: ranging from the earth-pillaging mad scientist of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger, to the Coal Fired Computers of Yokokoji-Harwood (YoHa), to Molleindustria’s smartphone game “Phone Story” which plays out on a smartphone’s screen the tangles of extraction, assembly, and disposal that are as much a part of the smartphone’s story as whatever uses for which the final device is eventually used. Cultural and artistic works, when they intend to, may be able to draw attention to the obscenity of the anthropocene.

The Anthrobscene and A Geology of Media are complementary texts, but one need not read both in order to understand the other. As part of the University of Minnesota Press’s “Forerunners” series, The Anthrobscene is a small book (in terms of page count and physical size) which moves at a brisk pace, in some ways it functions as a sort of greatest hits version of A Geology of Media – containing many of the essential high points, but lacking some of the elements that ultimately make A Geology of Media a satisfying and challenging book. Yet the duo of books work wonderfully together as The Anthrobscene acts as a sort of primer – that a reader of both books will detect many similarities between the two is not a major detraction, for these books tell a story that often goes unheard today.

Those looking for neat solutions to the anthropocene’s quagmire will not find them in either of these books – and as these texts are primarily aimed at an academic audience this is not particularly surprising. These books are not caught up in offering hope – be it false or genuine. At the close of A Geology of Media when Parikka discusses the need “to repurpose and reuse solutions in new ways, as circuit bending and hardware hacking practices imply” (A 41) – this does not appear as a perfect panacea but as way of possibly adjusting. Parikka is correct in emphasizing the ways in which the extractive regimes that characterized the paleotechnic continue on in the neotechnic era, and this is a point which Mumford himself made regarding the way that the various “technic” eras do not represent clean breaks from each other. As Mumford put it, “the new machines followed, not their own pattern, but the pattern laid down by previous economic and technical structures” (Mumford 2010, 236) – in other words, just as Parikka explains, the paleotechnic survives well into the neotechnic. The reason this is worth mentioning is not to challenge Parikka, but to highlight that the “neotechnic” is not meant as a characterization of a utopian technical epoch that has parted ways with the exploitation that had characterized the preceding period. For Mumford the need was to move beyond the anthropocentrism of the neotechnic period and move towards what he called (in The Culture of Cities) the “biotechnic” a period wherein “technology itself will be oriented toward the culture of life” (Mumford 1938, 495). Granted, as Mumford’s later work and as these books by Parikka make clear – instead of arriving at the “biotechnic” what we might get is instead the anthrobscene. And reading these books by Parikka makes it clear that one could not characterize the anthrobscene as being “oriented toward the culture of life” – indeed, it may be exactly the opposite. Or, to stick with Mumford a bit longer, it may be that the anthrobscene is the result of the triumph of “authoritarian technics” over “democratic” ones. Nevertheless, the true dirge like element of Parikka’s books is that they raise the possibility that it may well be too late to shift paths – that the neotechnic was perhaps just a coat of fresh paint applied to hide the rusting edifice of paleotechnics.

A Geology of Media and The Anthrobscene are conceptual toolkits, they provide the reader with the drills and shovels they need to dig into the materiality of digital media. But what these books make clear is that along with the pickaxe and the archeologist’s brush, if one is going to dig into the materiality of media one also needs a gasmask if one is to endure the noxious fumes. Ultimately, what Parikka shows is that the Situationist inspired graffiti of May 1968 “beneath the streets – the beach” needs to be rewritten in the anthrobscene.

Perhaps a fitting variation for today would read: “beneath the streets – the graveyard.”

_____

Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently working towards an MA in the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU. His research areas include media refusal and resistance to technology, ethical implications of technology, infrastructure and e-waste, as well as the intersection of library science with the STS field. Using the moniker “The Luddbrarian,” Loeb writes at the blog Librarian Shipwreck. He is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

Back to the essay

_____

Works Cited

Mumford, Lewis. 2010. Technics and Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mumford, Lewis. 1938. The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.