a review of McKenzie Wark, Molecular Red (Verso, 2015)

by Zachary Loeb

~

There are some games where a single player wins, games where a group of players wins, and then there are games where all of the players can share equally in defeat. Yet regardless of the way winners and losers are apportioned, there is something disconcerting about a game where the rules change significantly when one is within sight of victory. Suddenly the strategy that had previously assured success now promises defeat and the confused players are forced to reconsider all of the seemingly right decisions that have now brought them to an impending loss. It may be a trifle silly to talk of winners and losers in the Anthropocene, with its bleak herald climate change, but the epoch in which humans have become a geological force is one in which the strategies that propelled certain societies towards victory no longer seem like such wise tactics. With victory seeming less and less certain it is easy to assume defeat is inevitable.

“Let’s not despair” is the retort McKenzie Wark offers on the first page of Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene. The book approaches the Anthropocene as both a challenge and an opportunity, not for seeing who can pen the grimmest apocalyptic dirge but for developing new forms of critical theory. Prevailing responses to the Anthropocene – ranging from faith in new technology, to confidence in the market, to hopes for accountability, to despairing of technology – all strike Wark as insufficient, what he deems necessary are theories (which will hopefully lead to solutions) that recognize the ways in which the aforementioned solutions are entangled with each other. For Wark the coming crumbling of the American system was foreshadowed by the collapse of the Soviet system – and thus Molecular Red looks back at Soviet history to consider what other routes could have been taken there, before he switches his focus back to the United States to search for today’s alternate routes. Molecular Red reads aspects of Soviet history through the lens of “what if?” in order to consider contemporary questions from the perspective “what now?” As he writes: “[t]here is no other world, but it can’t be this one” (xxi).

Molecular Red is an engaging and interesting read that introduces its readers to a raft of under-read thinkers – and its counsel against despair is worth heeding. And yet, by the book’s end, it is easy to come away with a sense that while it is true that “there is no other world” that it will, alas, almost certainly be exactly this one.

Before Wark introduces individual writers and theorists he first unveils the main character of his book: “the Carbon Liberation Front” (xiv). In Wark’s estimation the Carbon Liberation Front (CLF from this point forward) represents the truly victorious liberation movement of the past centuries. And what this liberation movement has accomplished is the freeing of – as the name suggests – carbon, an element which has been burnt up by humans in pursuit of energy with the result being an atmosphere filled with heat-trapping carbon dioxide. “The Anthropocene runs on carbon” (xv), and seeing as the scientists who coined the term “Anthropocene” used it to mark the period wherein glacial ice cores began to show a concentration of green house gases, such as CO2 and Ch4 – the CLF appears as a force one cannot ignore.

Turning to Soviet history, Wark works to rescue Lenin’s rival Alexander Bogdanov from being relegated to a place as a mere footnote. Yet, Wark’s purpose is not to simply emphasize that Lenin and Bogdanov had different ideas regarding what the Bolsheviks should have done, what is of significance in Bogdanov is not questions of tactics but matters of theory. In particular Wark highlights Bogdanov’s ideas of “proletkult” and “tektology” while also drawing upon Bogdanov’s view of nature – he conceived of this “elusive category” as “simply that which labor encounters” (4, italics in original text). Bogdanov’s tektology was to be “a new way of organizing knowledge” while proletkult was to be “a new practice of culture” – as Wark explains “Bogdanov is not really trying to write philosophy so much a to hack it, to repurpose it for something other than the making of more philosophy” (13). Tektology was an attempt to bring together the lived experience of the proletariat along with philosophy and science – to create an active materialism “based on the social production of human existence” (18) and this production sees Nature as the realm within which laboring takes place. Or, as Wark eloquently puts it, tektology “is a way of organizing knowledge for difficult times…and perhaps also for the strange times likely to come in the twenty-first century” (40). Proletkult (which was an actual movement for some time) sought “to change labor, by merging art and work; to change everyday life…and to change affect” (35) – its goal was not to create proletarian culture but to provide a proletarian “point of view.” Deeply knowledgeable about science, himself a sort of science-fiction author (he wrote a quasi-utopian novel set on Mars called Red Star), and hopeful that technological advances would make workers more like engineers and artists, Bogdanov strikes Wark as “not the present writing about the future, but the past writing to the future” (59). Wark suggests that “perhaps Bogdanov is the point to which to return” (59) hence Wark’s touting of tektology, proletkult and Bogdanov’s view of nature.

While Wark makes it clear that Bogdanov’s ideas did have some impact in Soviet Russia, their effect was far less than what it could have been – and thus Bogdanov’s ideas remain an interesting case of “what if?” Yet, in the figure of Andrey Platonov, Wark finds an example of an individual whose writings reached towards proletkult. Wark sees Platonov as “the great writer of our planet of slums” (68). The fiction written by Platonov, his “(anti)novellas” as Wark calls them, are largely the tales of committed and well-meaning communists whose efforts come to naught. For Platonov’s characters failure is a constant companion, they struggle against nature in the name of utopianism and find that they simply must keep struggling. In Platonov’s work one finds a continual questioning of communism’s authoritarian turn from below, his “Marxism is an ascetic one, based on the experience of sub-proletarian everyday life” (104). And while Platonov’s tales are short on happy endings, Wark detects hope amidst the powerlessness, as long as life goes on, for “if one can keep living then everything is still possible” (80). Such is the type of anti-cynicism that makes Platonov’s Marxism worth considering – it finds the glimmer of utopia on the horizon even if it never seems to draw closer.

From the cold of the Soviet winter, Wark moves to the birthplace of the Californian Ideology – an ideology which Wark suggests has won the day: “it has no outside, and it is accelerating” (118). Yet, as with the case of Soviet communism, Wark is interested in looking for the fissures within the ideology, and instead of opining on Barbook and Cameron’s term moves through Ernst Mach and Paul Feyerabend en route to a consideration of Donna Haraway. Wark emphasizes how Haraway’s Marxism “insists on including nonhuman actors” (136) – her techno-science functions as a way of further breaking down the barrier that had been constructed between humans and nature. Shattering this divider is necessary to consider the ways that life itself has become caught up with capital in the age of patented life forms like OncoMouse. Amidst these entanglements Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” appears to have lost none of its power – Wark sees that “cyborgs are monsters, or rather demonstrations, in the double sense of to show and to warn, of possible worlds” (146). Such a show of possibilities is to present alternatives even when, “There’s no mother nature, no father science, no way back (or forward) to integrity” (150). Returning to Bogdanov, Wark writes that “Tektology is all about constructing temporary shelter in the world” (150) – and the cyborg identity is simultaneously what constructs such shelter and seeks haven within it. Beyond Haraway, Wark considers the work of Karen Barad and Paul Edwards, in order to further illustrate that “we are at one and the same time a product of techno-science and yet inclined to think ourselves separate from it” (165). Haraway, and the web of thinkers with which Wark connects her, appear as a way to reconnect with “something like the classical Marxist and Bogdanovite open-mindedness toward the sciences” (179).

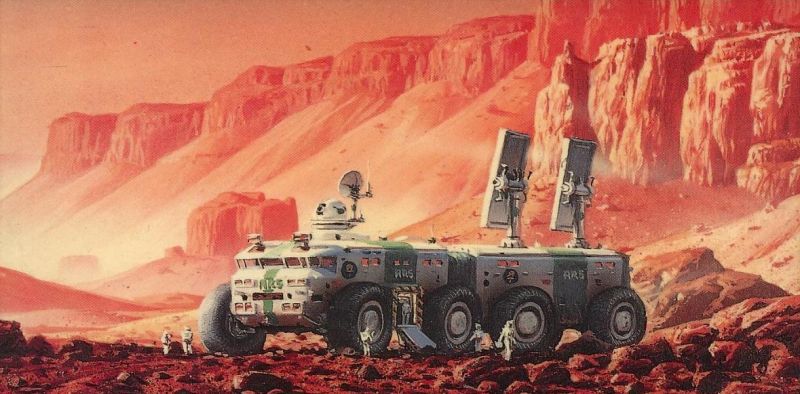

After science, Wark transitions to discussing the science fiction of Kim Stanley Robinson – in particular his Mars trilogy. Robinson’s tale of the scientist/technicians colonizing Mars and their attempts to create a better world on the one they are settling is a demonstration of how “the struggle for utopia is both technical and political, and so much else besides” (191). The value of the Mars trilogy, with its tale of revolutions, both successful and unsuccessful, and its portrayal of a transformed Earth, is in the slow unfolding of revolutionary change. In Red Mars (the first book of the trilogy, published in 1992) there is not a glorious revolution that instantly changes everything, but rather “the accumulation of minor, even molecular, elements of a new way of life and their negotiations with each other” (194). At work in the ruminations of the main characters of Red Mars, Wark detects something reminiscent of tektology even as the books themselves seem like a sort of proletkult for the Anthropocene.

Molecular Red’s tour of oft overlooked, or overly neglected thinkers, is an argument for a reengagement with Marxism, but a reengagement that willfully and carefully looks for the paths not taken. The argument is not that Lenin needs to be re-read, but that Bogdanov needs to be read. Wark does not downplay the dangers of the Anthropocene, but he refuses to wallow in dismay or pine for a pastoral past that was a fantasy in the first place. For Wark, we are closely entwined with our technology and the idea that it should all be turned off is a nonstarter. Molecular Red is not a trudge through the swamps of negativity, rather it’s a call: “Let’s use the time and information and everyday life still available to us to begin the task, quietly but in good cheer, of thinking otherwise, of working and experimenting” (221).

Wark does not conclude Molecular Red by reminding his readers that they have nothing to lose but their chains. Rather he reminds them that they still have a world to win.

Molecular Red begins with an admonishment not to despair, and ends with a similar plea not to lose hope. Granted, in order to find this hope one needs to be willing to consider that the causes for hopelessness may themselves be rooted in looking for hope in the wrong places. Wark argues, that by embracing techno-science, reveling in our cyborg selves, and creating new cultural forms to help us re-imagine our present and future – the left can make itself relevant once more. As a call for the left to embrace technology and look forward Molecular Red occupies a similar cultural shelf-space as that filled by recent books like Inventing the Future and Austerity Ecology and the Collapse-Porn Addicts. Which is to say that those who think that what is needed is “a frank acknowledgment of the entangling of our cyborg bodies within the technical” (xxi), those who think that the left needs to embrace technology with greater gusto, will find Molecular Red’s argument quite appealing. As for those who disagree – they will likely not find their minds changed by Molecular Red.

As a writer Wark has a talent for discussing dense theoretical terms in a readable and enjoyable format throughout Molecular Red. Regardless of what one ultimately thinks of Wark’s argument, one of the major strengths of Molecular Red is the way it introduces readers to overlooked theorists. After reading Wark’s chapters on Bogdanov and Platonov the reader certainly understands why Wark finds their work so engrossing and inspiring. Similarly, Wark makes a compelling case for the continued importance of Haraway’s cyborg concept and his treatment of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy is an apt demonstration of incorporating science fiction into works of theory. Amidst all of the grim books out there about the Anthropocene, Molecular Red is refreshing in its optimism. This is “Theory for the Anthropocene,” as the book’s subtitle puts it, but it is positive theory.

Granted, some of Wark’s linguistic flourishes become less entertaining over time – “the carbon liberation front” is an amusing concept at first but by the end of Molecular Red the term is as likely to solicit an eye-roll as introspection. A great deal of carbon has certainly been liberated, but has this been the result of a concerted effort (a “liberation front”) or has this been the result of humans not fully thinking through the consequences of technology? Certainly there are companies that have made fortunes through “liberating” carbon, but who is ultimately responsible for “the carbon liberation front?” One might be willing to treat terms like “liberation front” with less scrutiny were they not being used in a book so invested in re-vitalizing leftist theory. Does not a “liberation front” imply a movement with an ideology? It seems that the liberation of carbon is more of an accident of a capitalist ideology than the driver of that ideology itself. It may seem silly to focus upon the uneasy feeling that accompanies the term “carbon liberation front” but this is an example of a common problem with Molecular Red – the more one thinks about some of the premises the less satisfying Wark’s arguments become.

Given Wark’s commitment to reconfiguring Marxism for the Anthropocene it is unsurprising that he should choose to devote much of his attention to labor. This is especially fitting given the emphasis that Bogdanov and Platonov place on labor. Wark clearly finds much to approve of in Bogdanov’s idea that “all workers would become more like engineers, and also more like artists” (28). These are largely the type of workers one encounters in Robinson’s work and who are, generally, the heroes of Platonov’s tales, they make up a sort of “proto-hacker class” (90). It is an interesting move from the Soviet laborer to the technician/artists/hacker of Robinson – and it is not surprising that the author of A Hacker Manifesto (2004) should view hackers in such a romantic light. Yet Molecular Red is not a love letter to hackers, which makes it all the more interesting that labor in the Anthropocene is not given broader consideration. Bogdanov might have hoped that automation would make workers more like engineers and artists – but is there not still plenty of laboring going on in the Anthropocene? There is a heck of a lot of labor that goes into making the high-tech devices enjoyed by technicians, hackers and artists – though it may be a type of labor that is more convenient to ignore as it troubles the idea that workers are all metamorphosing into technician/artist/hackers. Given Platonov’s interest in the workers who seemed abandoned by the utopian promises they had been told it is a shame that Molecular Red does not pay greater attention to the forgotten workers of the Anthropocene. Yet, contemporary miners of minerals for high-tech doodads, device assemblers, e-waste recyclers, and the impoverished citizens of areas already suffering the burdens of climate change have more in common with the forgotten proletarians of Platonov than with the utopian scientists of Robinson’s Red Mars.

One way to read Molecular Red is as a plea to the left not to give up on techno-science. Though it seems worth wondering to what extent the left has actually done anything like this. Some on the left may be less willing to conclude that the Internet is the solution to every problem (“some” does not imply “the majority”), but agitating for green technologies and alternative energies seems a pretty clear demonstration that far from giving up on technology many on the left still approach it with great hope. Wark is arguing for “something like the classical Marxist and Bogdanovite open-mindedness toward the sciences…rather than the Heidegger-inflected critique of Marcuse and others” (179). Yet in looking at contemporary discussions around techno-science and the left, it does not seem that the “Heidegger-inflected critique of Marcuse and others” is particularly dominant. There may be a few theorists here and there still working to advance a rigorous critique of technology – but as the recent issues on technology from The Nation and Jacobin both show – the left is not currently being controlled by a bogey-man of Marcuse. Granted, this is a shame, for Molecular Red could have benefited from engaging with some of the critics of Marxism’s techno-utopian streak. Indeed, is the problem the lack of “open-mindedness toward the sciences” or that being open-minded has failed thus far to do much to stall the Anthropocene? Or is it that, perhaps, the left simply needs to prepare itself for being open-minded about geo-engineering? Wark describes the Anthropocene as being a sort of metabolic rift and cautions that “to reject techno-science altogether is to reject the means of knowing about metabolic rift” (180). Yet this seems to be something of a straw-man argument – how many critics are genuinely arguing that people should “reject techno-science”? Perhaps John Zerzan has a much wider readership than I knew.

Molecular Red cautions its readers against despair but the text has a significant darkness about it. Wark writes “we are cyborgs, making a cyborg planet with cyborg weather, a crazed, unstable disingression, whose information and energy systems are out of joint” (180) – but the knowledge that “we are cyborgs” does little to help the worker who has lost her job without suddenly becoming an engineer/artist, “a cyborg planet” does nothing to heal the sicknesses of those living near e-waste dumps, and calling it “cyborg weather” does little to help those who are already struggling to cope with the impacts of climate change. We may be cyborgs, but that doesn’t mean the Anthropocene will go easy on us. After all, the scientists in the Mars trilogy may work on transforming that planet into a utopia but while they are at it things do not exactly go well back on Earth. When Wark writes that “here among the ruins, something living yet remains” (xxii) he is echoing the ideology behind every anarcho-punk record cover that shows a better life being built on the ruins of the present world. But another feature of those album covers, and the allusion to “among the ruins,” is that the fact that some “living yet remains” is a testament to all of the dying that has also transpired.

McKenzie Wark has written an interesting and challenging book in Molecular Red and it is certainly a book with which it is worth engaging. Regardless of whether or not one is ultimately convinced by Wark’s argument, his final point will certainly resonate with those concerned about the present but hopeful for the future.

After all, we still have a world to win.

_____

Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently working towards an MA in the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU. His research areas include media refusal and resistance to technology, ethical implications of technology, infrastructure and e-waste, as well as the intersection of library science with the STS field. Using the moniker “The Luddbrarian,” Loeb writes at the blog Librarian Shipwreck and is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.