by Eugene Thacker

Review of Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie (Repeater, 2017)

For a long time, the horror genre was not generally considered worthy of critical, let alone philosophical, reflection; it was the stuff of cheap thrills, pulp magazines, B-movies. Much of this has changed in the ensuing years, as a robust and diverse critical literature has emerged around the horror genre, much of which not only considers the horror genre as a reflection of society, but as an autonomous platform for posing far-reaching questions concerning the fate of the humans species, the species that has named itself. These are sentiments that have preoccupied recent writing on the horror genre, much of which borrows from developments in contemporary philosophy, and is attempting to expand the confines of horror beyond the usual fixation on gore, violence, and shock tactics. This hasn’t always been the case. Even today, writing on genre horror often tends towards “list” books (of the type The Top 100 Italian Horror Films From 1977, Volume IV), or books that are basically print-on-demand databases (The Encyclopedia of Asian Ghost Stories from the Beginning of Time, and Before That). These are rounded out by a plethora of introductory textbooks and surveys, usually aimed at film studies undergraduates (e.g. Key Terms in Cultural Studies: Splatterpunk), and opaque academic monographs of Lacanian psychoanalytic semiotic readings of horror film that themselves seem to be part of some kind of academic cult.

While such books can be informative and helpful, reading them can be akin to the slightly woozy feeling one has after having gone down a combined Google/Wikipedia/YouTube rabbit-hole, emerging with bewildered eyes and terabytes of regurgitated data. However, recent writing on the horror genre takes a different approach, eschewing the poles of either the popular or the academic for a perhaps yet-to-be-named third space. One book that takes up this challenge is Mark Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie, published this year. (Fisher is likely known to readers through his blog K-punk, which had been running for almost two decades before his untimely death.) What Fisher’s study shares with other like-minded books is an interest in expanding our understanding of the horror genre beyond the genre itself, and he does this by focusing on one of the deepest threads in the horror genre: the limits of human beings living in a human-centric world.

As a case study, consider the opening passage from H.P. Lovecraft’s well-known short story “The Call of Cthulhu”:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

With this – arguably the most foreboding opener ever written for a story – Lovecraft sets the stage for what is really an extended meditation on human finitude. Originally published in the February 1928 issue of the pulp magazine Weird Tales, “Cthulhu” ostensibly brings together the perspectives of deep time and deep space to reflect on the comparatively myopic and humble non-event that is human civilization – at least that’s how Lovecraft himself puts it. It is well known that Lovecraft took cues from the likes of Edgar Allan Poe, Algernon Blackwood, and Arthur Machen – influences that he himself notes. Equally well known is Lovecraft’s notorious xenophobia (often expressed in his correspondence as outright racism). Yet in spite of – or because of – this, Lovecraft remained unambiguous in his own approach to the horror genre. In his numerous essays, notes, and letters, he notes, with an unflinching misanthropy, how a horror story should evoke “an atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces,” forces that point towards a “malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” The “monsters” in such tales were far from the usual line-up of vampires, werewolves, zombies, and demons – all of which, for Lovecraft and his colleagues, end up serving as mere solipsistic reflections of human-centric hopes and fears. They are often described in abstract, elemental, almost primordial ways: “the colour out of space,” “the shadow out of time,” or simply “the lurking fear.”

The story of “Cthulhu” itself – which details the discovery of a cult devoted to an ancient, malefic, Elder Deity vaguely resembling a oozing winged cephalopod emerging from a hidden tomb of impossibly-shaped Cyclopean black geometry foretelling not only the end of the world but the deeper futility of the entirety of human civilization – the story itself has since obtained a cult status among horror authors, critics, and fans alike. In the early 20th century, like-minded tales of cosmic misanthropy were written by Lovecraft contemporaries Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, and Robert Bloch, as well as by later authors of the weird tale such as Ramsey Campbell, Claitlín Kiernan, China Miéville, and Junji Ito. Like a slow-moving, tentacular meme, the Cthulhu “mythos” has reached far beyond the confines of literary horror. Film adaptations abound (the term “straight-to-video” no longer applies, but is still apt here). Video games, which nearly always end in despair and/or death. Role-playing games, complete with impossibly-shaped 10-sided black dice. A visit to any Comic Con will yield a dizzying array of comics, ‘zines, artwork, posters, bumper stickers, hoodies, Miskatonic University course catalogs, editions of the dreaded Necronomicon, and even Cthulhu plushies for the Lovecraft toddler. An industry is born. Today, distant cousins of Cthulhu can be seen in the Academy Award-nominated Arrival (2016), and the distinctly un-nominated burlesque that is Independence Day: Resurgence (2016). Cthulhu, it seems, has gone mainstream.

Amid all the fondness for such abysmal and tentacular monstrosities, it is easy to overlook the themes that run through Lovecraft’s short tale, themes at once disturbing and compelling, and which mark the tradition often referred to as “supernatural horror” or “cosmic horror.” When Lovecraft characters happen upon strange creatures like Cthulhu (or worse, the Shoggoths), they don’t have the typical reactions. “Fear” is too simple a term to describe it; it encompasses everything without saying anything. But neither are they overcome by the more literary affects of “terror” or “horror,” like the characters of an old gothic novel. They have neither the time nor the patience for the critical distance afforded by a psychoanalytic “uncanny,” or the literary structures of the “fantastic.” Confronted with Cthulhu, Lovecraft’s characters simply freeze. They become numb. They go dark. Frozen thought. They can’t wrap their heads around that is right before them. What they “feel” is exactly this “inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.” Forget the fear of death, I’ve just discovered a primordial, other-dimensional, slime-ridden necropolis of obsidian blasphemy that throws into question all human knowledge on this now-forsaken speck of cosmic dust we laughably call “our” planet.

Yet, in all their pulpy, melodramatic, low-brow seriousness, the questions raised by Lovecraft and other writers in Weird Tales are also philosophical questions. They are questions that address the limits of human knowledge in a rapidly-changing world, a world that seems indifferent to the machinations of science or doctrinal exuberance of religion, impassive before the hubris of technological advance or the lures of political ideology – a cold “crawling chaos” lurking just beneath the fragile fabric of humanity. What the characters of such stories discover (aside from the usual train of madness, dread, and, well, death) is a kind of stumbling humbleness, the human brain discovering its own limit, enlightened only of its own hubris – the humility of thought.

*

This theme – the limits of what can be known, the limits of what can be felt, the limits of what can be done – is central to Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie. This is markedly different from other approaches to horror, which, however critical they may seem, often regard the horror genre as having an essentially therapeutic function, enabling us to purge, cope with, or work through our collective fears and anxieties. This therapeutic view of horror often becomes polarized between reactionary readings (a horror story that promotes the establishing or re-establishing of norms) or progressive readings (a horror story that promotes otherness, difference, and transgression of norms). And yet, in the final analysis, it is also hard to escape the sense that there is a certain kind of solipsism to the horror genre, that it is we human beings that remain at the center of it all, who have either constructed boundaries and bunkers and have once again staved off another threat to our collective identity, or who have devised clever ways of creating hybrids, fusions, and monstrous couplings with the other, thereby extending humanity’s long dreamed-of share of immortality.

Whether reactionary or progressive, both responses to the horror genre involve a strategy in which the world in all its strangeness is transformed into a world made in our own image (anthropomorphism), or a world rendered useful for us as human beings (anthropocentrism). In spite of all the horrifying things that happen to the characters in horror stories, there is a sense in which the horror genre is ultimately a kind of humanism, a panegyric to the limitless potential of human knowledge, the immeasurable capacity for human feeling, the infinite promise of human sovereignty. This is, of course, not surprising, given the somber didactics of even the most extreme zombie apocalypses, vampiric mutations, or demonic plagues. Species self-interest is at stake. Humanity may be brought to the brink of extinction, only so that that same humanity may extend its mastery (self-mastery and mastery over its environment), and even obtain some form of ascendency over its own tenuous, existential status. Subtending the survivalist imperative of the horror genre and its pragmatic arsenal of mastering monsters of all kinds is another kind of mastery – a metaphysical mastery.

But this is only one way of understanding the horror genre. The insight of books like Fisher’s is that the horror genre is also capable of chipping away at this species-specific sovereignty, taking aim at the twin pillars of anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism. Instead of being concerned with species self-interest and mastery, such horror stories tend more towards humility, hubris, and even, in its darkest moments, futility. It is a project that is doomed to failure, of course, and perhaps this why so many of the characters in the tales of Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, or Izumi Kyoka find themselves in worlds that are both untenable and unlivable. They end up with nothing but a bit of useless quasi-wisdom, scribbling away madly in a darkened forest room trying to make sense of it all not making any sense. Or they detach themselves from the humdrum human world of plans and projects, finding themselves inexorably pulled headlong into the ambivalent abyss of self-abnegation. Or worse – they simply continue to exist. What results is what we might call a “bleak humanism” – a horror story interested in humanity only to the extent that humanity is defined by its uncertainties, its finitude, its doubts – the humility of being human.

Fisher’s terms are relatively clear. “What the weird and the eerie have in common is a preoccupation with the strange.” For Fisher, the strange is, quite simply, “a fascination for the outside […] that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience.” But the weird and the eerie are quite different in how they apprehend the strange. As Fisher writes, “the weird is constituted by a presence – the presence of that which does not belong.” There is something exorbitant, out-of-place, and incongruous about the weird. It is the part that does not fit into the whole, or the part that disturbs the whole – threshold worlds populated by portals, gateways, time loops, and simulacra. Fundamental presumptions about self, other, knowledge, and reality will have to be rethought. “The eerie, by contrast, is constituted by a failure of absence or by a failure of presence. There is something where there should be nothing, or there is nothing where there should be something.” Here we encounter disembodied voices, lapses in memory, selves that are others, revelations of the alien within, and nefarious motives buried in the unconscious, inorganic world in which we are embedded.

The weird and the eerie are not exclusive to the more esoteric regions of cosmic horror; they are also embedded in and bound up with quotidian notions of selfhood and the everyday relationship between self and world. The weird and eerie crop up in those furtive moments when we suspect we are not who we think we are, when we wonder if we do not act so much as we are acted upon. When everything we assumed to be a cause is really an effect. The weird and eerie are, ultimately, inseparable from the fabric of the social, cultural, and political landscape in which we are embedded. Fisher: “Capital is at every level an eerie entity: conjured out of nothing, capital nevertheless exerts more influence than any allegedly substantial entity.” There is a sense in which, for Fisher, the weird and the eerie constitute the poles of our ubiquitous “capitalist realism,” prompting us to re-examine not only presumptions concerning human agency, intentionality, and control, but also inviting a darker, more disturbing reflection on the strange agency of the inanimate and impersonal materiality of the world around us and within us.

Fisher’s interest in Lovecraft stems from this shift in perspective from the human-centric to the nonhuman-oriented – not simply a psychology of “fear,” but the unnerving, impersonal calm of the weird and eerie. As scholars of the horror genre frequently note, Lovecraft’s tales are distinct from genre fantasy, in that they rarely posit an other world beyond, beneath, or parallel to this one. And yet, anomalous and strange events do take place within this world. Furthermore, they seem to take place according to some logic that remains utterly alien to the human world of moral codes, natural law, and cosmic order. If such anomalies could simply be dismissed as anomalies, as errors or aberrations in nature, then the natural order of the world would remain intact. But they cannot be so easily dismissed, and neither can they simply be incorporated into the existing order without undermining it entirely. Fisher nicely summarizes the dilemma: “a weird entity or object is so strange that it makes us feel that it should not exist, or at least that it should not exist here. Yet if the entity or object is here, then the categories which we have up until now used to the make sense of the world cannot be valid. The weird thing is not wrong, after all: it is our conceptions that must be inadequate.”

*

This dilemma (which literary critic Tzvetan Todorov called “the fantastic”) is presented in unique ways by authors of the weird tale and cosmic horror. Such authors refuse to identify the weird with the supernatural, and often refuse the distinction between the natural and supernatural entirely. They do so not via mythology or religion, but via science – or at least a peculiar take on science. In cosmic horror, the strange reality described by science is often far more unreal than any vampire, werewolf, or zombie. Fisher highlights this: “In many ways, a natural phenomenon such as a black hole is more weird than a vampire.” Why? Because the existence of the vampire, anomalous and transgressive as it may seem, actually reinforces the boundary between the natural order “in here” and a transcendent, supernatural order “out there.” “Compare this to a black hole,” Fisher continues, “the bizarre ways in which it bends space and time are completely outside our common experience, and yet a black hole belongs to the natural-material cosmos – a cosmos which must therefore be much stranger than our ordinary experience can comprehend.” Science, for all its explanatory power, inadvertently reveals the hubris of the explanatory impulse of all human knowledge, not just science.

Authors such as Lovecraft were well aware of this shift in their approach to the horror genre. An oft-cited passage from one of Lovecraft’s letters reads: “…all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.” To write the truly weird tale, Lovecraft notes, “one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.” So much for humanism, then. But Fisher is also right to note that Lovecraft’s tales are not simply horror tales. As Lovecraft himself repeatedly noted, the affects of fear, terror, and horror are merely consequences of human being confronting an impersonal and indifferent non-human world – what Lovecraft once called “indifferentism” (which, as he jibes, wonders “whether the cosmos gives a damn one way or the other”). There is an allure to the unhuman that is, at the same time, opaque and obscure. As Fisher writes, “it is not horror but fascination – albeit a fascination usually mixed with a certain trepidation – that is integral to Lovecraft’s rendition of the weird…the weird cannot only repel, it must also compel our attention.”

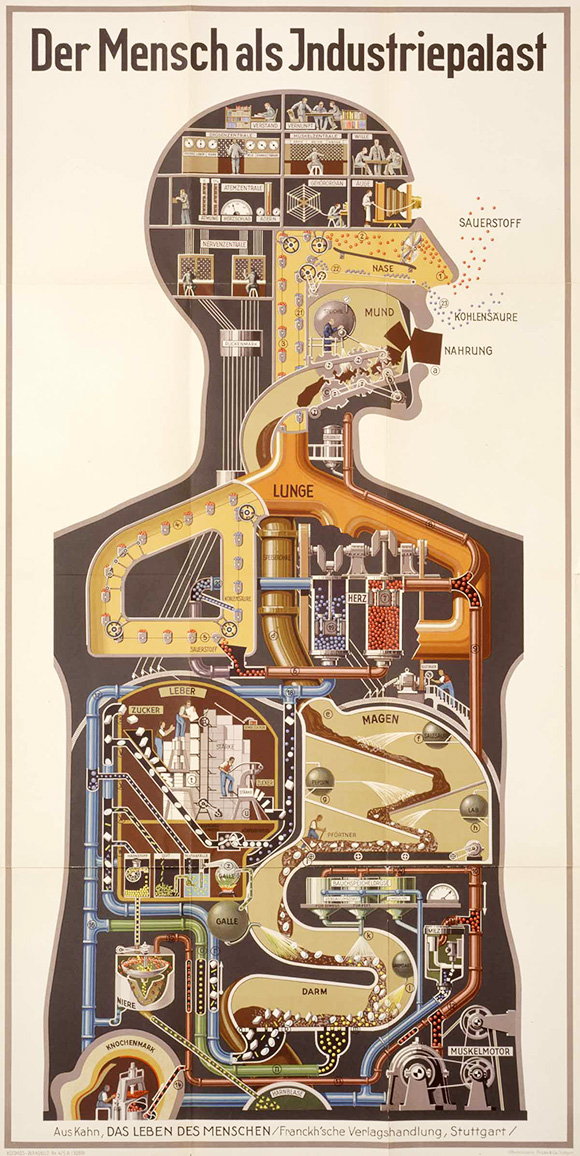

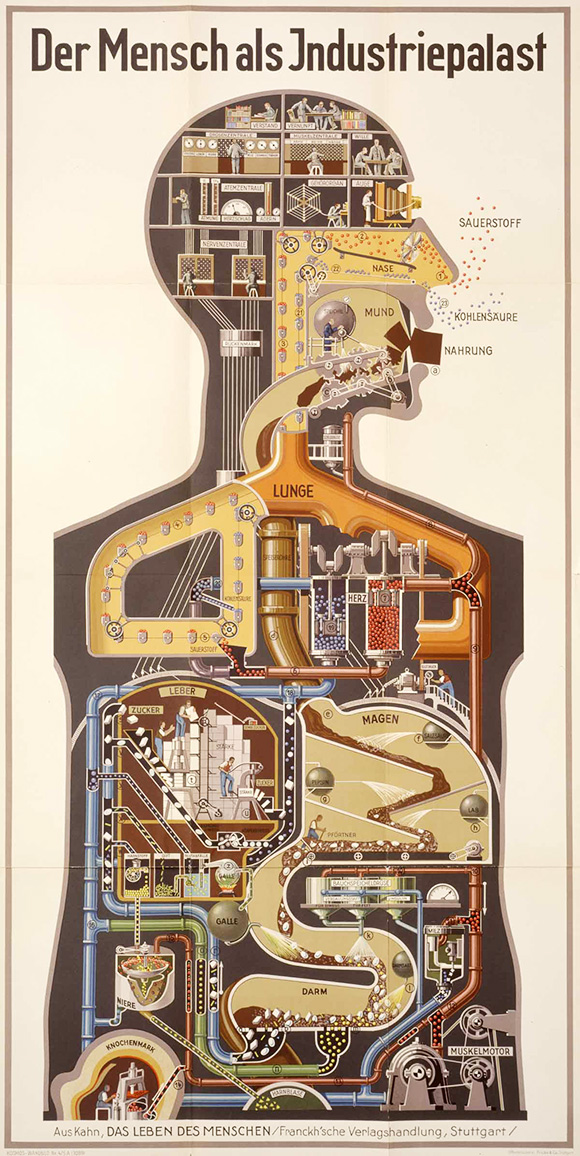

This reaches a pitch in Fisher’s writing on author Nigel Kneale and his series of Quatermass films and TV shows. The Quatermass and the Pit series, for instance, opens with the shocking discovery of an alien spaceship buried within the bowels of a London tube station (which station I will not say). The strange, quasi-insect remains inside the ship point to another, very different form of life than that of terrestrial life. But the science tells them that the alien spaceship is actually a relic from the distant past. It seems that not only geology and cosmology, but human history will have to be rethought. Gradually, the scientists learn that the alien relics are millions of years old, and in fact a distant, early progenitor of human beings. We, in turns, out, are they – or vice-versa. The Quatermass series not only demonstrates the efficacy of scientific inquiry, it puts forth a further proposition: that science works too well. “Kneale shows that an enquiry into the nature of what the world is like is also inevitably an unraveling of what human beings had taken themselves to be…if human beings fully belong to the so-called natural world, then on what grounds can a special case be made for them?” Reality turns out to be weirder and more eerie than any fantastical world or alien civilization. This is what Fisher calls “Radical Enlightenment,” a kind of physics that goes all the way, a materialism to the nth degree, even at the cost of disassembling the self-aware and self-privileging human brain that conceives of it. Reversals and inversions abound. What if humanity itself is not the cause of world history but the effect of material and physical laws that we can only dimly intuit?

This theme of Radical Enlightenment runs through Fisher’s book. While he does discuss works of fiction or film one would expect in relation to the horror genre (Lovecraft, Kubrick’s The Shining, David Lynch’s recent films), Fisher also offers ruminations on contemporary works (such as Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 film Under the Skin), as well as a number of evocative comparisons, such as a chapter on the weird effects of time loops in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film World on a Wire and Philip K. Dick’s novel Time Out Of Joint. There are also several surprises, including a meditation on the strange “vanishing landscapes” in M.R. James’s ghost stories and Brian Eno’s 1982 ambient album On Land. Also welcome is Fisher’s attentiveness to under-appreciated works in the horror genre, including the disquieting short fiction of Daphne du Maurier. In the span of a few carefully-written pages, Fisher follows the twists and turns of his twin concepts one chapter at a time, one example at a time, until it is revealed exactly how enmeshed the weird and the eerie are in culture generally.

*

The Weird and the Eerie is an evocative and carefully-written short study in cultural aesthetics. Far from the familiar line-up of vampires, zombies, and demons, Fisher’s eclectic examples speak directly to one of the central themes of the horror genre: the limits of human knowledge, the metamorphic shapes of fear, and the blurriness of boundaries of all types. His simple conceptual distinction quickly gives way to reversals, permutations, and complications, ultimately refusing any notion of a monstrous or alien unhumanness “out there”; with Fisher, the unhuman is more likely to reside within the human itself (or as Lovecraft might write it, “the unhuman is discovered to reside within the human itself”).

Many books on the horror genre are concerned with providing answers, using varieties of taxonomy and psychology to provide a therapeutic application to “our” lives, helping us to cathartically purge collective anxieties and fears. For Fisher, the emphasis is more on questions, questions that target the vanity and presumptuousness of human culture, questions regarding human consciousness elevating itself above all else, questions concerning the presumed sovereignty of the species at whatever cost – perhaps questions it’s better not to pose, at the risk of undermining the entire endeavor to begin with.

I should let the reader decide which approach makes more sense, given the weird and/or eerie “Waldo-moment” in which we currently find ourselves. But the weird and the eerie are scalable, pervading broad cultural structures as well as the minutiae of personal ruminations. I’ve known Fisher as a colleague for some time. About a week after I had agreed to do this review, I heard via email of Fisher’s suicide. Someone I knew was previously there, over there, doing what they do, they way we so often presume a person’s presence in between moments of punctuated interaction. And then, suddenly, they’re not there. About a week after this, The Weird and the Eerie arrived in the mail. It was hard not to pick up the book and feel it had a kind of aura around it, as if it was some kind of final statement, a last communiqué. I had it on the table in a short stack with other books, and I kept half-expecting it to also vanish, as if its very presence there were incongruous. I would occasionally pick up the book and flip through it, as if secretly hoping to discover pages that weren’t there before. But my copy was the same as all the others. Besides, isn’t that essentially what a book is, a last word written by someone either long dead or who will die in the future? Maybe all books are eerie in this way.

Eugene Thacker is the author of several books, including In The Dust Of This Planet (Zero Books, 2011) and Cosmic Pessimism (Univocal, 2015).