This essay has been peer-reviewed by “The New Extremism” special issue editors (Adrienne Massanari and David Golumbia), and the b2o: An Online Journal editorial board.

Introduction

This study produces a theoretical basis for understanding the political organization behind contemporary illiberal disinformation. I use the word “illiberal” because disinformation tends to attack liberal positions from both the left and the right, often deploying conspiracy theories and populist tropes. While I do not dispute the fact that liberal-oriented disinformation exists, the majority of disinformation is illiberal and pro-Russian in an “information war” waged against the post-war liberal order.[1]

Starbird, Arif, and Wilson (2018) found a “strategy of targeting, infiltrating, and shaping online activism” among information operations connected to Russia, while Hjorth and Adler-Nissen (2019) found conservatives up to 39% more likely to be exposed to disinformation.[2] It becomes important, then, to understand how disinformation flows influence popular discourse, and conservative discourse in particular, through the radicalization of social movements and the accentuation of certain aspects of them. In this study, I analyze the horizontal and vertical structure of disinformation networks, their ideological character, and their spatial scales.

First, I consider the form of illiberal ideology within disinformation within the historical patterns and generic definition of fascism, assessing its syncretism in light of a brand of fascist ideology associated with the Russian fascist Alexander Dugin. Second, I assesses the content of “junk news” dissemination via the “vertical” news syndicates of Russian media and the “horizontal” networks of news sites, blogs, and influence groups that help to spread disinformation through a process that I characterize as “refraction.”[3]

I call this process “refraction,” because it is similar to the way light entering a prism is bent into different colors. It is still the same conceptualization, but different components of it attune toward particular representations. By circulating the same “master narratives” of national decline and rebirth through an ostensibly diverse panoply of sources identified with differing and often combative ideologies—such as libertarian, far left, far right, and environmentalist—disinformation campaigns can gain the appearance of authenticity and media saturation.[4] As I show, these “master narratives” that are “refracted” into different angles or approaches often bear a consistent alignment with “multipolar” goals. This strategic approach involves both the production of “junk news” across a diverse tableau of websites, which tend to be either political or non-political, and its dissemination, far more often by autonomous actors than by automated bots.[5] I do not investigate the psychology of willing actors disseminating “junk news,” because that would require an entire study of its own, involving different methods and data sources.

Thirdly, to add a practical component to my study, I analyze the function of these media networks in light of Russia’s active measures during the 2016 presidential elections. I find that disinformation has been aided and facilitated through infiltration within and exploitation of broader left-wing narratives casting opposition to Russia-supported disinformation as “McCarthyism.” In this way, I show that disinformation can succeed when given cover by sectors of the media already deemed credible by a significant audience, and that even when utilized by the left, most often serves the interests of the far right.

I. Fascism and Geopolitics

In this section, I compare the major ideological positions and strategic devices of contemporary disinformation networks to those of the far-right and fascist networks. I describe fascist syncretism in relation to arguably the most influential fascist in the world, Alexander Dugin. I further describe the key geopolitical aspects of Dugin’s ideology as multipolarism, Traditionalism, and Eurasianism, and explore the strategic importance of “entryism,” or infiltration, to his movement. This ideological analysis helps to illustrate the material influences and tendencies of specific disinformation disseminators, while also forming a backdrop for broader information campaigns.

Fascism, Right and Left

Understanding the flows of disinformation across scales in their proper political context requires a precise understanding of the political ideologies involved, including fascism, the populist radical right, and the hard left. Close inspection of fascist ideology reveals a tacit tendency to fuse opposing positions in order to produce a syncretic, quasi-populist combination of elitism and popular mobilization. We need to understand fascism before elaborating the similarities and differences of the populist radical right and the “hard left,” which tend to engage in collaborative efforts to defeat liberalism at the polls or in the streets. I first take a genealogical approach, then a typological approach toward recognizing fascism’s relationship to other movements and ideologies in order to get at a “generic definition” of fascism.

Fascism must be understood as both an ideology with both revolutionary and reactionary features. The roots of fascism lie in reactionary juridical aspirations to total counter-revolution, which in the late 19th century contributed to a populist movement that appealed to workers, shopkeepers, and the upper-middle class in opposition to republicanism.[6] As the crisis of liberalism manifested in its failure to fulfill its own egalitarian promise, fascists exploited the violent rupture caused by revolutionary socialist opposition. Following the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917 and the Italian victory in World War I, fascism emerged as a movement of vanguard aesthetes, intellectuals, and war veterans who called for the obliteration of liberal bureaucracies in favor of a futuristic system based on classical archetypes reproduced by the New Man’s march, unfettered by compromise, into a world of national will. Fascists suffused the reactionary tradition inherited by proto-fascists like the antisemitic trade union, Les Jaunes, with modern elements of collectivism and ultra-nationalism joined with elitism.[7] In opposition to undeserving liberal elites who created the conditions for chaos by offering lip service to equality, they promised their own version of a future where “natural” elites could gain support from a purportedly anti-capitalist system.[8]

While fascists exploit revolutionary anti-capitalist responses to the failure of liberalism, they also benefit from a history of antisemitism and nationalism within the social movements of the 19th and early 20th Century.[9] I use the term “hard left” to connote such groups identified as left wing who nevertheless perceive the world through the inflexible lens of authoritarianism and conspiracy theories.[10] The “hard left” often abandons precise analyses of material conditions in favor of attacking individuals and groups like the Rothschilds, George Soros, the Bilderberg Group, or an esoteric “Zionist cabal” as the prime movers of world-historical events. Historically, such disdain for supposed conspiratorial “masters of the universe” has led members of the hard left to promote populist syntheses of right and left-wing opposition to liberalism.[11] At this juncture between hard left and radical right, fascist groups can gain hegemony by deploying syncretic ideology toward the generation of socio-political conditions more amenable to fascist movements. At the same time, these movements fail to deliver on their “revolutionary” promises, typically succeeding merely in providing a smoother socio-political basis for the accumulation of capital.[12]

Thus, fascists glean from revolutionary movements the auspices of a virile state even while finding “classical liberal” allies in their crushing of the radical mass movements they pretended to truly represent.[13] Fascist advocacy of a “national revolution” against technocratic liberal democracy deploys populist tropes against the rising tide of grassroots leftwing movements and invited collaborations with the anti-parliamentary left.[14] The fruits of these efforts emerged in Italy with an aesthetic-nationalist movement that openly conflated right and left terminology in efforts to produce a “New Man” who would bring about the “New Age.”[15] Hence, fascism in its early form represented an undoubtedly right-wing political ideology that offered a totalitarian solution to dissatisfaction with parliamentary compromises—a national revolution that would restore older forms of sovereignty, re-establishing patriarchy at the heart of a revival of classical myths and archetypes. In this sense, I follow Roger Griffin’s “new consensus” definition of fascism as palingenetic ultranationalism—i.e., the rebirth of a mythical nation founded on myths of sovereignty and projected into a futurist “New Age” through the nomination of a subjectivity created by and creating a fusion of different, often conflicting and paradoxical ideologies, ideas, and commitments.[16]

Syncretism

Syncretism is not merely the fusion of left and right but the assemblage of contradictory concepts into a quasi-spiritual worldview (e.g., national socialism, elitist populism, esoteric political religion, and völkisch futurism) held together as if by magic. Although in general it exposes massive internal conflicts, syncretism enables the particular spatio-temporal adaptation of fascist movements to localized and historical phenomena in order to insinuate “palingenetic ultranationalism” into different conditions, while also opening the possibility of entryism within different political and social groups. In the same way, syncretism becomes a tool through which disinformation networks appropriate pre-existing online cultures, political groups, and social movements, warping their discourses toward the objectives of illiberal populism. Intentional disinformation flows suffuse not only right and left, but disparate socio-political subcultures from the organic food movement to anti-vaxxers to flat earth theories for the development of a syncretic geopolitical subject that conforms to the desires of authoritarian leaders.

George L. Mosse, among the forerunners of the “new consensus,” Sternhell, one of its critical contemporaries, and Emilio Gentile, a luminary in the current study of fascism, have all offered incisive interpretations of such tendencies, as has antifascist scholar Umberto Eco. For Mosse, fascism represented both the incitement of revolution against liberal democracy and the subsequent taming of that revolution through the incorporation of the masses—an “anti-bourgeois bourgeois revolution.”[17] Hence, through a conditioned populist resentment against the current bourgeois elites, fascism empowered frustrated groups within the bourgeoisie to overthrow the “system” and replace it with their own.

In his well-known essay, “Ur-Fascism,” Eco contends with the frustration at the heart of fascism and its implications for the “fuzziness” of fascist ideology. Fascism becomes “an all-purpose term because one can eliminate from a fascist regime one or more features, and it will still be recognizable as fascist.” Only through this physical acting out of ideological fallacies can fascism oppose the “analytical criticism” that would otherwise level it, Eco argues.[18]

Throughout his work, Zeev Sternhell observes similar tendencies at root in fascism—namely fascist Georges Valois’s calling for a “fusion of nationalism and socialism.”[19] The currents that emerged in France and Italy, using syndicalist anti-parliamentarianism to fan the flames of mass action in the service of an idealized national myth, produced a collective, right-wing revolutionary subject. Hence, fascism emerged from a sense that the violent overcoming of intellectual and political oppositions could form an ideology of action over ideas.

In his important essay, Roger Eatwell expands on the contextualization of fascism, identifying a “spectral-syncretic model” for understanding its motivations. Drawing from the themes of “natural history,” geopolitics, political economy, and “leadership, activism, party and propaganda,” Eatwell approaches fascism across different stages and scales in order to obtain a fuller understanding of its necessary components.[20] Fascism could not reconcile entirely the ideological divisions of its time and was left with a partial incorporation of a number of different positions—the New Man and the classical archetype; Christianity and anti-clerical paganism; irrationalism and science; private property and social welfare.[21] For these reasons, fascism’s totalitarian approach to “political culture” actually spread immense ideological confusion that further enabled the Leader to make apparently pragmatic decisions.

This final point appears also in the work of Emilio Gentile on “Fascism as a Political Religion.” Gentile argues that “this syncretism of different beliefs within fascist ideology permitted the existence of diverse approaches, but none of these could hope to present itself as the only authentic interpretation of the ‘faith.’” The ideological split between fascism and the Catholic Church had to be closed by Fascism’s ultimate triumph over the Church as its genuine representative. Similarly, German fascism “‘Aryanized’ and ‘Germanized’ Christ and God.”[22] In other iterations of fascism throughout the world, for example with Brazil’s Integralistas, syncretism enabled the adoption of “Fascist rationale and leadership… but only in association with local and cultural traditions and innovations carefully selected and emphasized by leading intellectuals.”[23]

A Brief Introduction to Multipolarity

The syncretic alternative media networks that engaged in political discourse surrounding the 2016 presidential elections in the US shared in common a commitment to “anti-establishment” politics. Across international and local scales, this alternative media ecosystem typically framed Russia as a leading, global opponent to the establishment. The approach of syncretic alternative media networks, then, promoted a geopolitical understanding of the North Atlantic as the liberal, establishment base, sympathizing instead with Eurasian hegemony in a “multipolar” context.

Multipolarism emerged in the Soviet Union during the late-60s and 1970s as a realpolitik fix for the crises of Khrushchevian internationalism. Among its most important progenitors, Yevgeni Primakov developed crucial ties between the Soviets and the Ba’athist Parties in both Iraq and Syria.[24] Through multipolarism, the Soviets could support authoritarian-conservative nationalism as a bastion against the US and the State of Israel, which it deemed the global imperialist powers. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Primakov helped translate Soviet era policies, including intelligence operations, into the modern Russian Federation while serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs and then Prime Minister from 1996-1999.[25] After President Boris Yeltsin’s pro-Western tenure, the regime of Vladimir Putin drifted increasingly toward a “multipolarism” dedicated to Russia as an independent, Eurasian world power somewhere between empire and “civilization state.”[26] Today, Putin’s policies are often viewed as a vacillation between Primakov’s “pragmatic” approach and the syncretic approach advocated by the most radical progenitor of “multipolarism,” Russian fascist Alexander Dugin.[27]

Multipolarism suits Dugin’s brand of fascism, because it stems from the Soviet Union’s support for the authoritarian fusion of nationalist and socialist tendencies in opposition to liberal capitalism.[28] As a National Bolshevik who longed for an ultranationalist form of the Soviet Union, Dugin set the groundwork for the junction of left and right as a feature of disinformation campaigns that often promote Russian media over and against establishment “mainstream media,” and in some cases are openly affiliated with Duginist ideology. However, disinformation involves a complex field of shared interests, overlapping audience, and collaborative partnerships in which Dugin and his ideology play an important and influential role—perhaps even to the chagrin of some of its other progenitors.

Dugin’s Eurasianism and Traditionalism

Dugin’s geopolitical ideology, which he calls “Eurasianism,” stems from an effort to join multiple regions and diverse political and spiritual approaches into an overarching, imperial construct stretching from Dublin to Vladivostok.[30] Configured in accordance with a “multipolar” strategy, Dugin’s Eurasia would echo an agenda similar to the European New Right and its chief advocate, Alain de Benoist, who is one of Dugin’s intellectual heroes.[31] Arguing for a heterogeneous assemblage of homogenous ethnostates, such a multipolar world relies on authoritarian regimes masked as direct democracy through predicates of a community solidarity based on strict “natural hierarchies” associated with staunch, “blood and soil” patriarchy.[32]

Hence, Dugin argues for a Traditionalist approach that endorses far-right Russian Orthodoxy, Protestant fundamentalists, the kind of reactionary Catholicism advocated by Rexist Leon Degrelle and practiced by members of the Spanish Falange, and hardline Shi’a Islam, as long as they remain within discrete geographic regions. Dugin’s most influential book to date, Foundations of Geopolitics, situates post-war fascists within the genealogy of “classical” geopolitical theorists. Instead of full-blown Hitlerism, then, Dugin maintains a position of “conservative revolution,” referring to far-right Nazi collaborators like Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger as his immediate influences.[33] Despite his efforts to place some distance between himself and the old Nazi Party core, Dugin’s analysis results in a racist, occult screed about the prior existence of a Hyperborean “root race” of pure Aryan types.[34]

Nationalist Entryism

Amid the reaction to Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution in Russia, Duginism was transmitted into a street-level movement of “managed nationalism” that, alongside youth organizations like the Gladiators, Nashi, and the Slavic Union, could defeat liberal opposition to Putin’s administration within Russia, itself.[35] Dugin also helped create a new political party called Rodina (Motherland) alongside former left-wing economist and LaRouche associate, Sergei Glazyev, hoping to support Putin through “controlled democracy” by using nativism to draw working class votes from the Communist Party.[36] Although Rodina transitioned to the leadership of Sergei Rogozin, whose geopolitical vision is quite different from Dugin’s, Rodina and its leadership continued to draw leftists into a right-wing opposition to liberalism.

In accordance with their worldview, Duginists and similar far-right activists worked to enter the anti-globalization movement through an illiberal “anti-globalist” approach. Among the most open instances of entryism occurred among Dugin’s followers in Italy, where Claudio Mutti and his colleagues, Claudio Terciano and Tiberio Graziani, among other right-wing extremists, were allowed to affiliate with the Assisi-based Campo Antimperialista.[37] Although recent literature on the subject suggests that their interventions ended due to the controversy that it raised, the milieu fostered by active participation of fascists with left-wing anti-imperialists provided the space for important left-wingers to convert to the Eurasianist cause.[38] By the mid-2000s, the Campo had drawn in Holocaust denier Claudio Moffa and an important Marxist theorist named Costanzo Preve, who gravitated toward the Duginists, publishing with their presses and appearing with them at conferences.

In conjunction with the Russian Anti-Globalization Movement, later recast as the Anti-Globalization Movement of Russia, members of Rodina would emerge as an illiberal, reactionary force merging right and left through collaboration with other ostensibly left-wing, anti-imperialist groups from the Campo Antimperialista to associated left-wing groups in the US like the Workers World Party.[39] This considerable left-right crossover compounded ongoing organizational crossover across national and international scales, particularly over the question of geopolitical “multipolarism.”[40] Along with other interlinked think tanks like the German Center for Eurasian Studies and the Polish European Center of Geopolitical Analysis, propaganda organs like Graziani’s Geopolitica, and international conferences like Iran’s New Horizon, the Anti-Globalization Movement of Russia, Campo Antimperialista, and Workers World Party contributed to the development of an extensive international network supported by Russian soft power and largely favorable to the Kremlin’s geopolitical initiatives.

Conclusion

The ideology and strategy of “managed nationalism,” or state support of right-wing groups to dismantle the gains of the left, emerged across international and local scales in relation to Dugin’s participation in the ideological and practical reactionary movements of the early-mid-2000s. With the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the later conflicts in Syria and Ukraine, the Kremlin’s rhetoric and practices pivoted more toward Eurasianism, bringing Dugin and his associates greater influence.[41] For instance, Dugin’s compatriot, Sergei Glazyev, who opined about a Jewish plot to replace Russians, became Putin’s advisor on Eurasianism.[42] This geopolitical pivot brought with it a new form of “hybrid warfare” (often framed as “the Gerasimov doctrine”), which advances cyber-attacks, propaganda techniques, and disinformation in accordance with many of the “net-centric war” theory outlined by Dugin and developed further by the Command and Control Research Program of the Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense, in which Russia strives to win physical contests before they happen by controlling the information space through information operations that delegitimize their geopolitical opposition.[43]

It is important to note that the theories that drive modern covert action are opaque by nature, and Dugin’s is one of at least three leading, and often interwoven, influential theoretical formulations of hybrid war (with Evgeny Messner and Igor Panarin), which cannot be fully exposited in this article. In the next section, however, I will show the integral participation of Duginist networks in disinformation campaigns, and the deployment of discursive and strategic approaches associated with Duginism—particularly, as Starbird, Arif, and Wilson show, the “strategy of targeting, infiltrating, and shaping online activism,” syncretism, and geopolitical positions aligned with multipolarity.[44] Through this effort, we can gain a clearer understanding of the usage of extremism within disinformation campaigns.

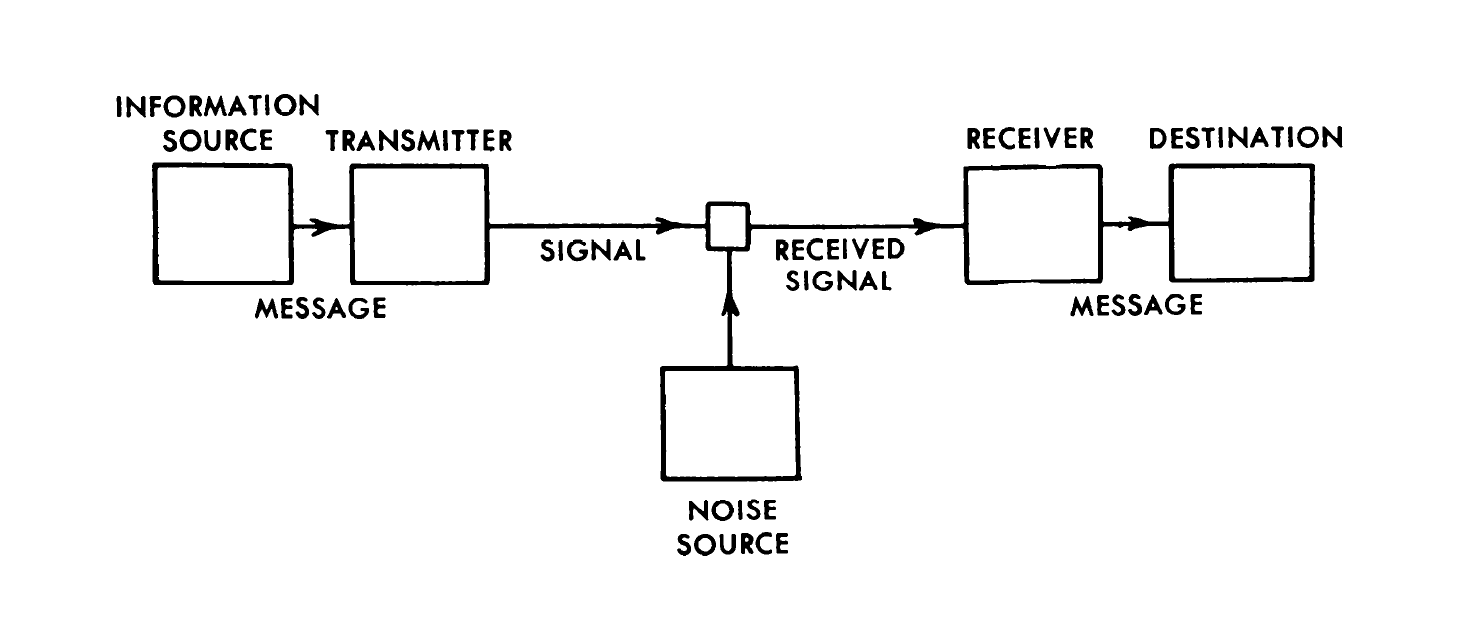

II. The Vertical and Horizontal Structure of Illiberal Disinformation Networks

When presenting the media ecosystem that forwards the Kremlin’s foreign policy interests, the obvious imperative falls on describing its state-funded and state-run media, which have at many points spearheaded online disinformation. This section first unpacks Russian state media available in the West through RT and Sputink in Horbyk’s terms, as “a vertikal—a Soviet‐time term connoting a strictly hierarchical and monolithic power apparatus—in the media system.”[45] Next, it explores some different horizontal networks of influence groups and websites that help disseminate pro-Russian disinformation. Lastly, it shows tacit integration between the two.

The “Vertikal”

The origins of RT are somewhat murky, but can generally be located in RIA Novosti. A state-run Russian news agency, RIA Novosti created a non-profit called TV-Novosti, which then founded RT as “Russia Today” in 2005 amid the “managed nationalism” campaign. While TV-Novosti’s non-profit status gives RT the pretense of autonomy from direct state control, the organization is considered extremely important for the Kremlin’s domestic and foreign strategies. RT first emerged to promote Russian culture, but the experience of the 2008 conflict in Georgia and contested 2011 Russian legislative elections led to its transition into “a political tool to undermine the American position in global politics.”[46]

During Occupy Wall Street, RT promoted left-wing opposition to liberal economics by hosting a number of left activists from the US and other countries in Europe. In discussions ranging from economics to geopolitics, leftists found the attention they felt they deserved, and a platform to spread their ideas to millions of people. At the same time, RT provided platforms to Eurasianists like German Duginist Manuel Ochsenreiter, Polish activist Mateusz Piskorski, and Claudio Mutti’s colleague Tiberio Graziani. Piskorski would go to Polish jail on charges of spying for Russia and China, while Ochsenreiter stands implicated in a 2019 “false flag” firebombing of a Hungarian cultural center in Ukraine, which prosecutors believe is connected to Russian secret services.[47] As well, RT promoted conspiracy theorists like “great replacement” theorist Renaud Camus and French “9/11 truth” activist Thierry Meyssan, whose own media node, Voltaire Network, includes Dugin associate and Rosneft spokesperson Mikhail Leontyev among its stable of writers.[48] In this manner, RT groups together left-wing and right-wing illiberalism corresponding to a quasi-populist coalition in favor of the Kremlin’s geopolitical imperatives (e.g., support for Bashar al-Assad, Russia’s semi-clandestine occupation of the Donbass, and Euroskepticism).

RT’s efforts provide an aura of respectability to marginal Duginist activists, thus boosting their pet causes and projects. For instance, RT promoted an obscure fascist commentator named Joaquin Flores as an informed pundit. Hailing from Los Angeles, Flores helped moderate a left-wing MySpace forum in the early 2000s before moving to fascism based on his rejection of feminism and liberalism. He joined a spin-off of the fascist skinhead group American Front, called New Resistance, run by long-time fascist James Porrazzo. New Resistance helped bring Flores into the international Duginist network, through which he moved to Belgrade, developed political affinities with the far-right Serbian Radical Party, and helped broaden the Duginist online network. In the early 2010s, Flores joined the Center for Syncretic Studies (CSS), which focuses on developing the Duginist foundations of Eurasianism and multipolarism.[49] CSS’s media site, Fort Russ, provides news and analysis from a Duginist perspective. Through this work, Flores became a well-known figure among Duginists, but remained entirely obscure until RT’s promotion opportunities.

Another Duginist given public attention by RT is Andrew Korybko. One of the more prolific commentators in the Duginist think tank Katehon, Korybko has written a book about hybrid war addressing Syria and Ukraine, and between 2015-2016 he placed seven articles in the website of Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, which likely developed aspects of the strategy for intervention in the 2016 elections.[50] The leader at the time, a Lieutenant General of the Foreign Intelligence Service named Leonid Reshetnikov, also sat on the board of Katehon.[51] Though at this point Korybko maintains a high stature in Russian political life, RT’s attention both represented and propelled his ascent.

Hence, RT not only facilitates the spread of Duginist geopolitics through the promotion of its exponents, but it has become a key conduit relaying informational presentation from think tanks to the public. As well, RT came to promote conspiracy theories as ways of confusing its audience’s understanding of key issues in order to advance Russian policy interests. In the words of scholar Ilya Yablokov, RT became “a specific tool of Russian public diplomacy aimed at undermining the policies of the US government and, in turn, defending Russia’s actions.”[52] In particular, Yablokov observes, RT promoted the “underdog” vision of Vladislav Surkov, mastermind of “sovereign democracy” and “managed nationalism”—“conveying Russia as a ‘speaker’ on behalf of the third-world nations excluded from the US-led ‘New World Order.’” However, Yablokov argues that RT is not truly Duginist, since the “ambiguity and heterogeneity of the ideological foundation of the current Russian political regime makes anti-Americanism the only constant element of RT’s agenda.”[53] Such an orientation enables the support of populist political parties, usually of the radical right, which the Kremlin hopes to support as an increasingly viable alternative to the EU and NATO.

In December 2013, RIA Novosti and radio service Voice of Russia were brought together under the name Russiya Segodnya, which literally translates to Russia Today. Although the Kremlin denies that Russiya Segodnya and RT are connected, they share the same editor-in-chief, Margarita Simonyan.[54] Within a year, Russiya Segodnya reconfigured the previously-existing Voice of Russia into Sputnik News, which would feature international news and podcasts under the name Radio Sputnik. In the words of Roman Horbyk, “The launch of new state news agencies Rossiya Segodnia (based on the restructured RIA Novosti) and Sputnik, with budgets in the billions, marked the completion of a vertikal—a Soviet‐time term connoting a strictly hierarchical and monolithic power apparatus—in the media system.”[55] Created to counter “propaganda promoting a unipolar world,” Sputnik more explicitly delivered their terms of multipolarism and more openly advocated for left-right syncretism against “Atlantic liberalism.”[56] Sputnik would become more radical than RT in forwarding conspiracy theories, Eurasianism, and alliances between fascists and leftists in opposition to liberalism.

Additional fascinating examples of Russian state systems percolating into the alternative media ecosystem are Redfish, the New Eastern Outlook (or Journal-NEO), and Strategic Culture. Promoting stories of social unrest in opposition to neoliberalism, Redfish is a project supported by the Kremlin that bears the aesthetics of an independent alternative news startup giving it more social media appeal than RT, from which most of its publicly-associated employees hailed in 2018.[57] The publication of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, New Eastern Outlook produces conspiracy theories about Rothschilds and George Soros and Islamophobic material, and hosts articles by Duginist Catherine Shakhdam and conspiracy theorist Vanessa Beeley, among others. Although New Eastern Outlook has a far smaller reach than Sputnik and RT, it provides more appearance of diversity within a media ecosystem largely controlled by think tanks and the vertikal.[58] Similarly, the Strategic Culture Foundation emerged from a Moscow think tank run by former-Soviet politician, Yuri Prokofiev, to undermine US foreign policy, hosting disinformation purveyors who appear to present autonomous and unbiased findings on their commentary site, Strategic Culture.[59] In short, the post-Soviet vertikal functions as controlled state media despite giving the appearance, on occasion, of an autonomous “free press” that appeals to left-of-center dissenters and lay geopolitical analysts who feel underrepresented in Western media.

Horizontal Soft Power and the Alternative Media Ecosystem

If Russian state media marks a vertikal, soft-power groups and alternative media organizations make up the accompanying horizontal networks. Here, the term “horizontal” is used to connote relative autonomy from the state but not equal relations between sites. Some sites are obviously more privileged than others, as is reflected in differential support from the vertikal, but they nevertheless remain engaged in a common system of propaganda “refraction.”

Since Journal-NEO and Strategic Culture are directly connected to the Russian state, I have grouped them in the vertikal, but they behave more like horizontal network nodes, because their affiliations are opaquer. Soft power groups are often funded by the Kremlin or its loyal oligarchs, and typically promote round tables, academic conferences, and the dissemination of information and disinformation. The latter work of dissemination is commonly related to an alternative media ecosystem that engages a network of editors and journalists in the publication of articles that often reuse the same pro-Kremlin narratives with different “packaging” depending on the ideological bent of the site and its audience.[60] Soft power networks rely on fascists and far-right nationalists developing institutions that will propagate pro-Russian influence.

Soft-power groups explored by Anton Shekhovtsov’s monograph, Russia and the Western Far Right, include the group around the Italian journal Geopolitica, founded by Graziani, and its related French group, the Institute of Democracy and Cooperation, founded by Natalya Narochnitskaya, who ran for election as a Rodina candidate. These two groups have had overlapping membership—for instance Narochnitskaya is on Geopolitica’s “Scientific Board” and US libertarian John Laughland has featured on the board of both.[61] Other inter-connected “think tanks,” publications, and institutions, such as Piskorski’s European Center of Geopolitical Analysis and Ochsenreiter’s German Center for Eurasian Studies, join in the promotion of pro-Kremlin propaganda efforts, including “election observation” for fraudulent elections in Eastern Europe.[62] While these European networks hold import for regional politics, an interlinked US-centered network similarly exists to support Russia’s geopolitical interests across the Atlantic.

Many of the current influence groups within the US promoting Russia’s agenda through disinformation have a common “roof” through the efforts of far-right political operator Edward Lozansky. Born in the Soviet Union, Lozansky moved to the US toward the end of the Cold War in order to lobby in favor of Russian dissidents. He gained useful friends among the US New Right, including Heritage Foundation founder, Paul Weyrich, who would prove instrumental in replacing regimes formerly under Soviet control with far-right nationalists. Lozansky worked to set up a new “American University in Moscow” and a related “think tank,” which would group together “non-interventionist” journalists and political activists. Through his university, Lozansky produced a semi-annual “Russia Forum” where both pro-Russia leftists and rightists, including influential Congressmen and prominent media figures, mingle and share ideas on media, policy, education, and political strategy.[63]

As of mid-2018, “Research fellows” at Lozansky’s university included members of RT and the Russian Institute of Strategic Studies, as well as the head of Dugin’s Centre for Conservative Studies, Mark Sleboda, and Daniel McAdams of the Ron Paul Institute, who described himself as a “Traditionalist” in his Twitter profile before changing it in 2019.[64] Another “research fellow,” Gilbert Doctorow, worked through the Russia Forum in 2014 to re-found the 1970s pro-détente group, the American Committee for East-West Accord (ACEWA), with co-founder Stephen F. Cohen.[65] A contributing editor to The Nation magazine, Cohen helped bring important political and business figures onto the board of ACEWA, while the group took on far-right journalist James Carden to edit its website.[66] The ACEWA’s launch later that year in Brussels brought together a round table including Aymeric Chauprade, a far-right advisor to the Front National’s Marine Le Pen who had recently returned from “observing” the illegal referendum in Crimea (Chauprade is also a member of the red-brown Izborsky Club think tank with Dugin, Glazyev, Leontyev, and Narochnitskaya, and is also on the “scientific committee” of Graziani’s Geopolitica).[67] Lozanksy himself has appeared with Dugin both on television and at conferences, as well as fascist ideologues like Alain de Benoist and former WikiLeaks attaché Israel Shamir. Aside from co-authoring articles with Lozansky in the far-right Washington Times, Doctorow openly advocates de Benoist’s vision of an illiberal populism fusing left and right.[68]

Hence, Doctorow helped to foster in the ACEWA a pro-Kremlin organization linked to other soft-power groups around Europe through Lozansky’s Russia Forum. Along with the Russia Forum, Doctorow helped give a pro-alt-right propaganda site called Russia Insider its start. Russia Insider’s North American donations were “processed” by Consortium News, another pro-Kremlin site featuring syncretic political activists.[69] Among Consortium News’s stable of authors is Caitlin Johnstone, who calls for “shameless” alliances between the left and right in favor of the Kremlin’s interests, Pepe Escobar, who regularly appears at the conferences of Iran’s sanctioned, anti-Semitic New Horizon organization, and Max Blumenthal, who has been criticized for promoting conspiracy theories about Syria’s White Helmets and advocating a “multipolar world.”[70] Other fellows listed at Lozansky’s university think tank include a blogger named Anatoly Karlin, who has moved from his Da Russophile blog to the far-right Unz Review, and disbarred attorney Alexander Mercouris of alternative media site, The Duran, whose director hosts a program on RT. As well, Patrick Armstrong, James Jatras, and Anthony Salvia are interesting mentions on Lozansky’s list, because they were also listed as authors for Global Independent Analytics (GIAnalytics), a site that New Knowledge finds closely associated with the Internet Research Agency’s “troll factory.”[71] A glance at a sample of the members of Lozansky’s think tank who are connected to alternative news outlets and the sites they represent shows impressive content sharing [Table 1].

| American University in Moscow | Ron Paul Institute | The Duran | Consortium News | Russophile/Unz Review | GIAnalytics | Rank |

|

| Edward Lozansky | X | X | X | 3rd | |||

| Daniel McAdams | X | X | X | X | 2nd | ||

| Alexander Mercouris | X | X | X | X | 3rd | ||

| Gilbert Doctorow | X | X | X | 3rd | |||

| Anatoly Karlin | X | X | 4th | ||||

| Patrick Armstrong | X | X | X | * | X | 2nd | |

| James Jatras | X | X | X | X | X | 1st | |

| Anthony Salvia | X | X | 4th | ||||

| Rank |

1st | 3rd | 2nd | 4th | 2nd | 4th |

Table 1. An examination of cross-referenced authors and websites linked to the American University in Moscow’s think tank. The grey boxes signify that the author is a high-ranking member of or core writer for the site.

* Note that Patrick Armstrong appears to post in Consortium News’s comments, but does not appear to be an author for the site.

I analyzed the content sharing and cross-promotion of authors associated with the American University in Moscow in Table 1 by searching for the authors’ bylines within the websites in question. An “X” signifies that the author’s work appears in or is associated with the site or group in question. Association is used with regards to the American University in Moscow, while content inclusion is used with the other four sites. The most cross-published author in the group associated with Lozansky that I studied is Jatras, with Mercouris close behind and Lozansky, McAdams, and Doctorow tied for third. The sites that have cross-published every author are The Duran and the Unz Review, with Consortium News proving the most selective in this context. At the same time, Consortium News does quote McAdams as “a highly respected former Foreign Service Officer possessing impeccable credentials,” and while the Ron Paul Institute is only the second most selective, it also hosts an article quoting Gilbert Doctorow as a US-Russia relations analyst without an indication of bias. It is important to note that this set is only representative of alternative figures associated in 2018 with the American University in Moscow according to its website, and other connections with other sites are explored further in this article.

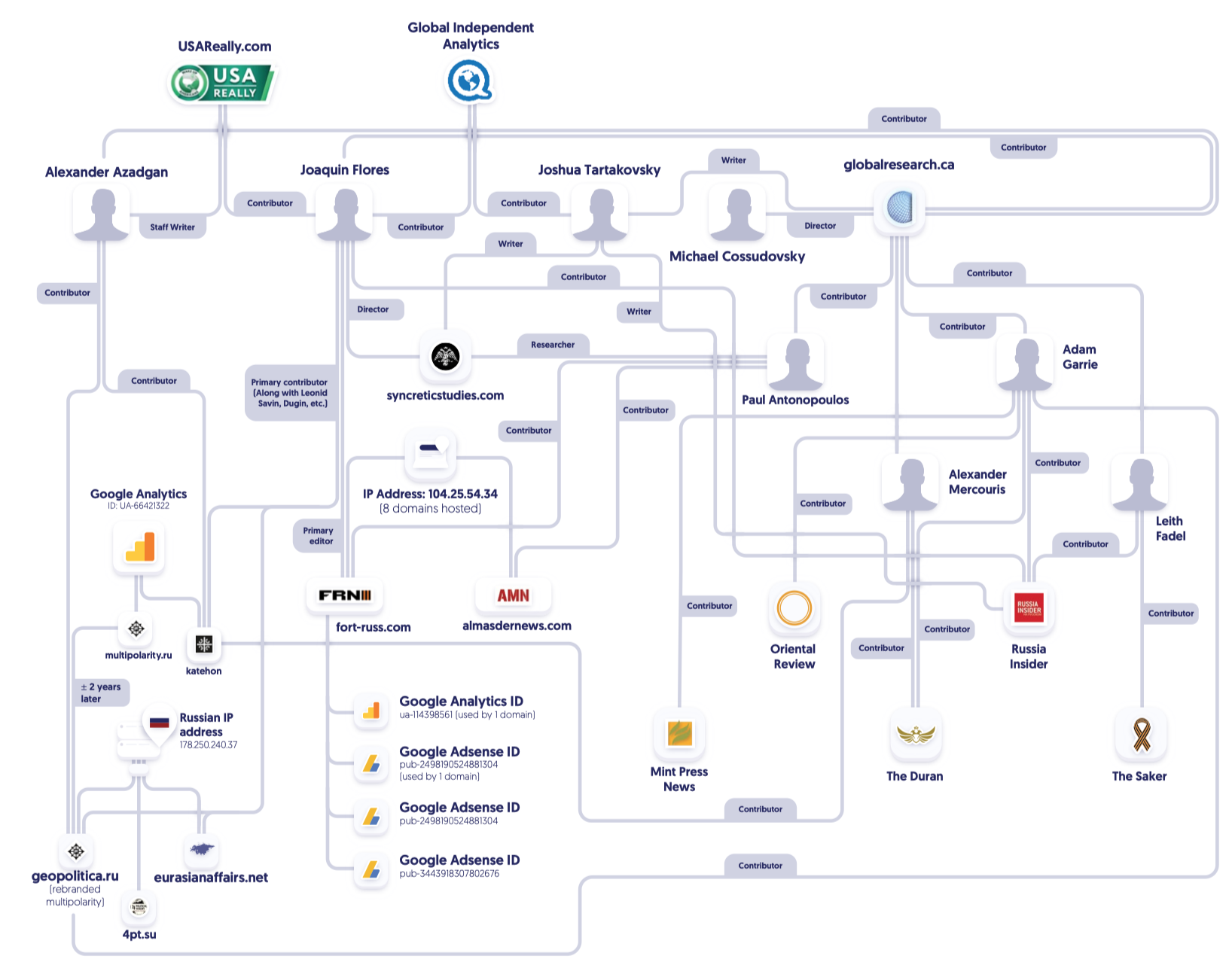

I could not find evidence that GIAnalytics, the group most directly tied to the Internet Research Agency by the Mueller Report, cross-published any of the other authors; however, the site is offline now, making it difficult to research their archives. Other than Lozansky’s think tank, GIAnalytics has the highest membership out of the sample of groups represented at the American University in Moscow, with Consortium News in close second. Importantly, Joaquin Flores features as a member of GIAnalytics, and his site Fort Russ found promotional space at Lozansky’s Russia Forum along with Consortium News and Russia Insider. This again shows open Duginist involvement within the “alternative media” networks mobilized and supported by Lozansky in the context of his institutions. Figure 1 shows clear connections between GI Analytics and other groups in the sample, such as Russia Insider and The Duran (DiResta et al., 2018).

Lozansky and his fellows also receive promotion and airtime on Russian state media, particularly Sputnik Radio. One show host at Sputnik, Brian Becker, is the head of Party for Socialism and Liberation, a spin-off of the hard-left Workers World Party.[72] On his show Loud & Clear, Becker has hosted Mercouris, as well as McAdams of the Ron Paul Institute, whose board also includes Geopolitica and Institute for Democracy and Cooperation member, John Laughland. Duginist Mark Sleboda made it on Loud & Clear more than forty times in the first two years of the program. Another Duginist, Catherine Shakhdam, was hosted more than twenty times during the same time period. Lozanksy, himself, joined the Sputnik News program of Scottish socialist John Wight, Hard Facts, for interviews promoting the “multipolar world.”[73] Of course, RT has helped forward the same voices, for instance hosting Doctorow, Becker, and McAdams on the same CrossTalk program in September 2016 for a conversation about “Increased Tensions” between Russia and the US. The promotion of horizontal networks joining the hard left to Duginists through the vertikal suggests that the Eurasianist approach to the “multipolar world” plays a role in overdetermining the geopolitical oppositions between nationalism and internationalism, particularly through the uses and distortions of the notion of anti-imperialism.[74]

Site Overlap and Content Sharing

Studies of site metrics and content sharing have exposed significant overlap both among “master narratives” and audiences who visit pro-Russian sites responsible for disinformation. This overlap suggests that a strong subculture of internet users regularly access these websites for their understanding of current events. It also renders explicit different scales of dissemination, from vertical to horizontal to mainstream.

In December 2017 and January 2018, I ran the Audience Overlap Tool available through Alexa.[75] Using proprietary algorithms, the Audience Overlap Tool identifies and ranks the sites that audience members use to travel from and to a given site, and then presents a visualization of those sites based on their own audience. Thus, it both visually and numerically represents the clustering of sites. It should be noted that audience overlap does not necessarily imply shared ideology. A site might share an audience because people click to and from a ruthless critique. However, using empirical data and qualitative analysis, we can identify ideologically similar sites from ideologically opposed ones. This becomes complicated given the syncretic characteristics of disinformation schemes; however, where their agreement on specific issues becomes more pronounced than their general ideological differences, they are still considered similar and their clustering is considered to be representative of their similarity rather than their opposition.

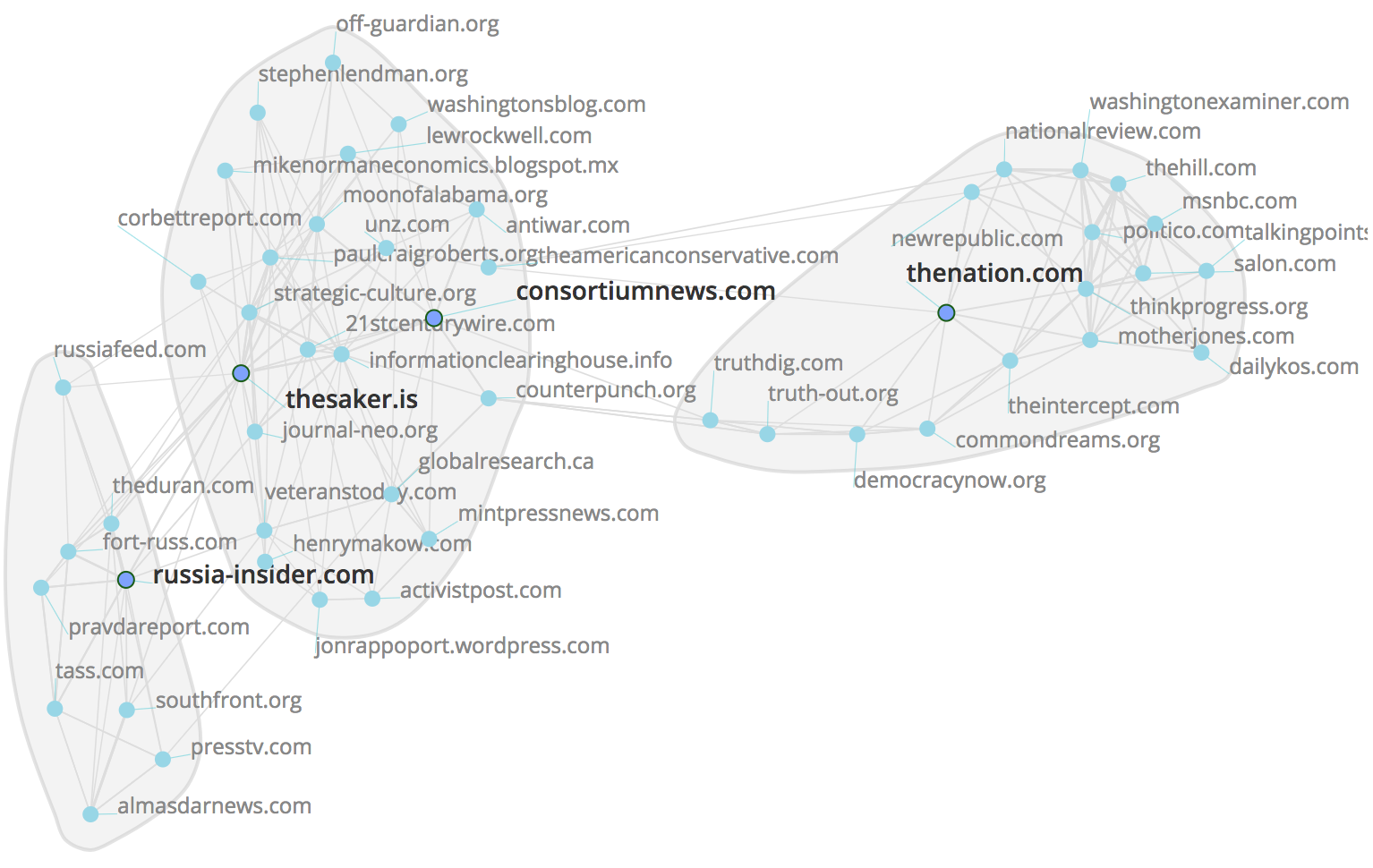

It should also be noted that clustering becomes dependent on the variables, or sites, selected in relation to one another. I chose Russia Insider, Consortium News, and The Nation because they have important relationships in associated personnel, and added The Saker as another site anchored within the illiberal disinformation ecosystem. While those individual sites do not change with regards to their individual site cross-overs, the overall visualization reflects the way that clustering occurs in relation to the four sites. Had I chosen different sites within the same network, the overall clustering would not appear the same.

When I ran Alexa’s model, I observed significant clustering among Russian sites (vertical) clearly connected to Western-based pro-Russia media (horizontal), which shows a clear relationship with more mainstream sites autonomous from the disinformation ecosystem [Figure 2]. The Nation appears to present this bridge from the horizontal to the mainstream, while Russia Insider seems to present the site furthest embedded within the Russian media. As we will see in the next section, this composition appears to be further evidenced when examining the usage of “McCarthyite” as a slur during 2016 presidential elections.

In an investigation into the site metrics (clicks from incoming and outgoing readers) of the most frequented Russia-friendly site in December 2017, The Duran, turned up a cluster of related sites—especially The Saker and 21stCenturyWire, which harbor the closest affinity for Russian politics and Duginist positions outside of those self-described Russian websites, themselves. Most of its viewers clicked over from Facebook, Google, and YouTube; however, importantly, Russia Insider and rt.com accounted for the fourth and fifth most clicks, showing how the audience flutters between networks.

The fourth and fifth most entered sites from The Duran were Russia Insider and The Saker, which received more than 54,000 unique hits per month. The audiences for the Duran and The Saker show significant audience overlap with Russia Insider and Fort Russ, according to Alexa, suggesting a strong correlation between its politics and those of the Duginist network. Significantly, among the highest search engine keywords for those clicking on The Duran was “George Soros,” indicating a high degree of anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists enjoying their articles.[76]

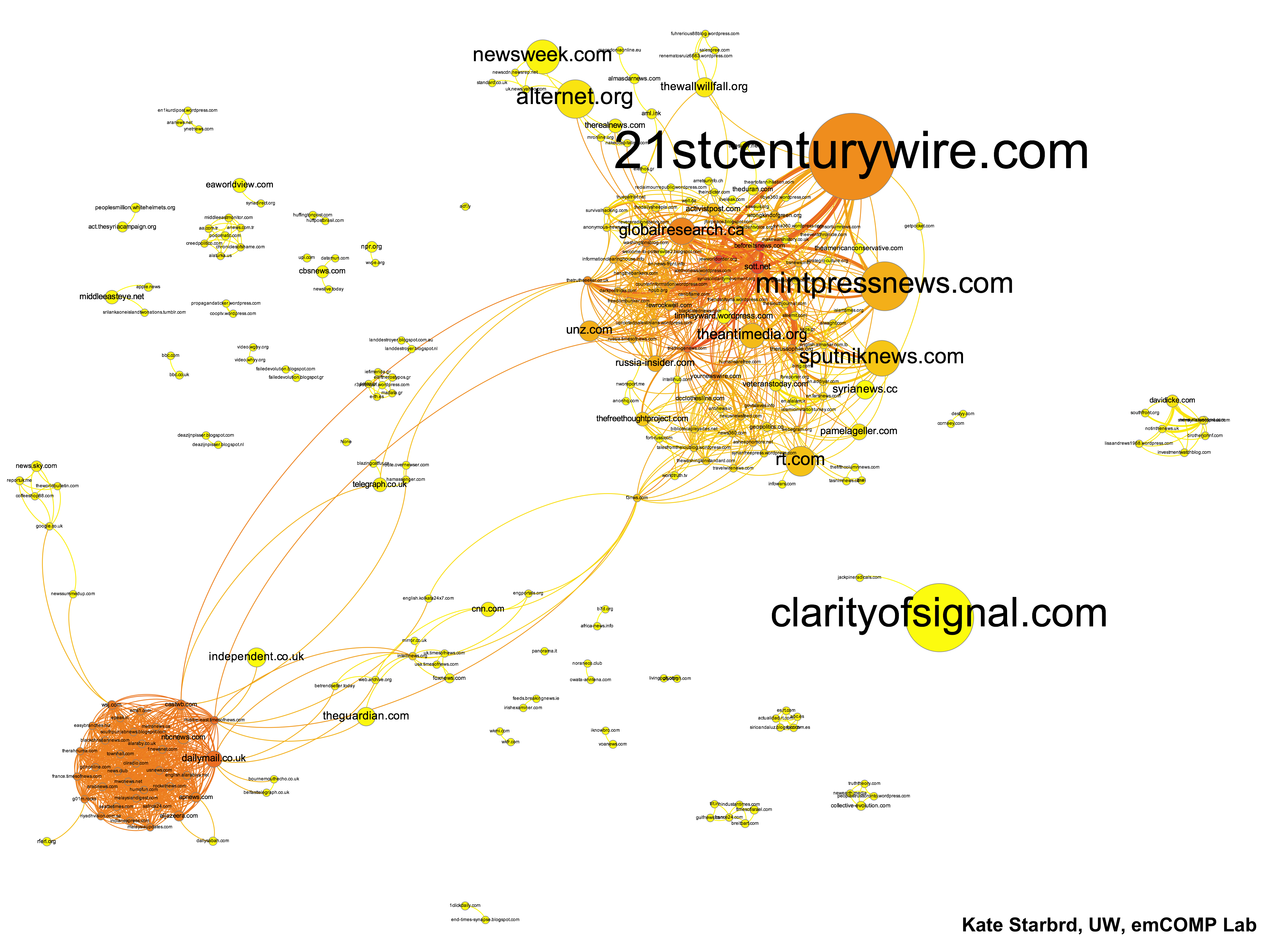

This complex assemblage of groups not only shares significant audience overlap but engages in important content sharing. In an important academic study of this syncretic approach, “Ecosystem or Echosystem? Exploring Content Sharing across Alternative Media Domains,” scholars Kate Starbird, et. al., identify the same websites appearing to produce alternative frameworks and approaches to news stories, such as The Russophile, 21st Century Wire, The Duran, and Consortium News [Figure 3].[77] Each of these sites maintains “strong political themes reflecting distinct (and in some cases, seemingly conflicting) ideologies—including anti-imperialist left, libertarian, conservative and alt-right; as well as other more niche ideological leanings, including explicit anti-Semitism,” the authors state. Yet, the authors importantly conclude that these websites “are publishing the same content, but inside very different wrappers.”[78] A number of the same sites also appear in the study conducted by New Knowledge for the US Senate, because they either participated in or were directly supported by Russian disinformation “factory,” the Internet Research Agency.[79]

Table 2 assesses overlapping members across Lozansky’s think tank, the content-sharing conspiracy theory sites in Starbird et al, 2018; those associated with GI Analytics according to New Knowledge’s 2018 white paper; those who the 2019 Stanford study found published fake authors attributed to the GRU, [80] and the Alexa model’s findings of overlapping sites between Russia Insider, Consortium News, The Saker, and The Nation. It should be noted that lack of affiliation of a member of a site with the American University in Moscow’s think tank does not indicate no connection to Russian media, while the reverse is true: affiliation suggests a person is engaged in pro-Russian illiberal media efforts.

| Lozansky fellow | Starbird | New Knowledge |

Stanford | Rank | |

| Consortium News | X | X | 3rd | ||

| Fort Russ | X | X | X | 2nd | |

| The Saker | X | X | 3rd | ||

| The Duran | X | X | X | X | 1st |

| Russia Insider | X | X | X | X | 1st |

| RT | X | X | 3rd | ||

| Global Research | X | X | X | X | 1st |

| Unz/DaRussophile | X | X | X | 2nd | |

| 21st Century Wire | X | 4th | |||

| MintPressNews | X | X | X | X | 2nd |

| Voice of Russia/Sputnik | X | X | 3rd |

Table 2. An X marks representation of affiliation of a member of the website with Lozansky’s think tank and presence in studies on disinformation content sharing (Starbird et al., 2018), Russian meddling (DiResta et al., 2018), fake authors (DiResta and Grossman, 2019), and audience overlap (based on 2018 Alexa search).

Overlap in Table 2 mostly indicates whether the site is connected to Lozansky’s think tank, and whether it is observed as part of a disinformation ecosystem that involves significant content sharing (Starbird et al., 2018), audience overlap (Alexa), and is connected to the Internet Research Agency (Diresta et al., 2018) or published fake authors associated with the GRU’s disinformation efforts (Diresta and Grossman, 2019). The highest overlap occurs with The Duran, associated with Lozansky fellow, Alexander Mercouris; Global Research, a conspiracy theory site founded by former LaRouchite Michel Chossudovsky (who is also on the board of Graziani’s Geopolitica); and Russia Insider, associated with ACEWA cofounder, Consortium News member, and Lozansky co-author, Gilbert Doctorow. Next come Unz, Fort Russ, and MintPressNews. Voice of Russia, RT, The Saker, and Consortium News come in third place. The least overlap comes with 21st Century Wire, a site founded by a former associate editor of Alex Jones’s Infowars that includes, among other things, a 45-minute interview with Dugin.

By embracing politics associated with different factions and sides in political conflict, media can appeal to different audiences and bind them through a common thread. In most cases I studied, that commonality would be geopolitical. By spreading disinformation across discrete political platforms, the alternative media “echo-system,” as some have called it, could exploit popular discontent against “the establishment” and desire for radical analysis through a process of media saturation. Yet the saturation, whereby multifarious platforms disseminate the same content by sharing one another’s articles, carries a second effect of uniting those discrete ideologies in a singular geopolitical agenda. For this reason, the horizontal disinformation syndicate studied above can be seen as a combined, if decentered and complex, system with syncretic characteristics. While it is largely self-organized, it relies on subtle cues within a hierarchy of privileged interests to adapt and reproduce media narratives often spontaneously in real time.

Through this process, the syncretic media system engages in what I call refraction—a splitting and polarizing movement that reinforces the distinction between ideological “wrappers” that produce a “multipolar” assemblage of ideological positions out of a single ur-narrative under the aegis of geopolitics. While they vie for attention and publicity toward their own particular tendencies and leaders, the procedure tends to promote illiberal politics on an affective range and in matters of policy, whereby the commonality between ideologies is typically some variance of anti-establishment politics, and the establishment is generally viewed as “neoliberal.” Relying on Noberto Bobbio’s explication of the difference between left and right that hinges on the assertion of equality, the present study therefore finds that illiberal syncretism, while supportive of some left-wing tendencies, ultimately reproduces an authoritarian and therefore inegalitarian assemblage. There is perhaps no better example of the tacit support for authoritarian, populist politics than the disinformation media landscape’s engagement in the 2016 presidential elections in the US.[81]

III. Disinformation as Cover for Active Measures: A Case Study of the 2016 US Presidential Elections

During the lead-up to the November 2016 elections, some of the same journalists and media critics who denied Russian intervention and called people who recognized it “McCarthyites” were, at the same time, involved in pro-Kremlin influence groups with ties to Russian soft power organizations. Late in March 2019, special prosecutor Robert Mueller submitted his report to the Attorney General, William P. Barr, who promptly offered a summary declaring insufficient evidence in the case of collusion between the presidential campaign of Donald Trump and Russian officials. While many across the alternative news scene celebrated what they deemed vindication for casting doubts on collusion between Trump and Russia, they did not focus on the part of the Attorney General’s summary that described the special prosecutor’s findings of Russian intervention in the 2016 elections. Indeed, Mueller’s team exposed a sweeping disinformation operation extending from Kremlin-supported sources, and found that Russia’s GRU hacked the the Democratic National Committee and Clinton advisor John Podesta.[82]

The final part of this study describes the influence of alternative media sites, supported by disinformation, in promoting the narrative that the assertion of Russian election meddling represented “McCarthyism.” Because of my findings of overlap described above, I was unsure where the narrative of “McCarthyism” would have begun. I created a vertikal hypothesis that the term was initially fielded by disinformation agents among the vertikal and then percolated through the horizontal media system into the mainstream. My alternative hypothesis was that the narrative emerged in the horizontal network and found re-enforcement in the vertikal. A null hypothesis identifying “no difference” would suggest the narrative began and was propogated chiefly by actors not associated with either horizontal or vertikal.

After a careful, qualitative study of the evidence, my alternative hypothesis proved more adequate to explain the complex dissemination of the “McCarthyite” narrative than either the null or primary hypotheses. The claims of “McCarthyism” actually began with media figures connected to Russian disinformation circles closest to the US mainstream. Hence, in this case, there was a directional movement between Russian media, the horizontal structure of supporting sites, and the mainstream, but it flowed in the opposite direction from the one that would indicate a top-down, Russian operation, per se. Even if those using the accusation were still engaged in each cluster within the overall system, what I observed was something more like an incentive-based marketplace in which Russian media helped select and amplify particular networks and signals coming from discrete, autonomous and semi-autonomous actors within a syncretic network engaging in broad content-sharing.

Methods

My research question was whether pro-Kremlin influence operations helped forward pro-Trump narratives in the lead-up to the 2016 elections, and if so, what were their relationship to the international fascist movement? To answer this question, I performed a qualitative content analysis of the media listed by Google News referencing “McCarthyite” and “McCarthyism,” and then cross-referenced my findings with a Nexis Uni® search of the same terms with regards to the US presidential elections, from the end of the primary races to the end of Election Week. With this time span, we can understand better how the term “McCarthyite” increased in usage, as well as the extent to which its usage changed in relation to events taking place during the Republican and Democratic primary campaigns—particularly the release of the hacked Podesta and DNC emails.

The popularity of particular articles using the term, as well as their impact on other articles and the extent to which they were linked to, reveal key influencers with regards to the usage of the term and the context through which its meaning is constructed. The total number of articles featuring “McCarthyite” and “McCarthyism” in 2015 was 1,464, increasing by 21% to 1,772 in 2016, and again by 104% to 3,611 the year after that, illustrating a significant growth in the terms’ usage. The most referenced person was Donald Trump, followed by Hillary Clinton, Barrack Obama, Vladimir Putin, and Bernie Sanders in that order, with the content indicating that most articles on “McCarthyism” were opposed to the notion that his campaign was supported by Russian active measures.

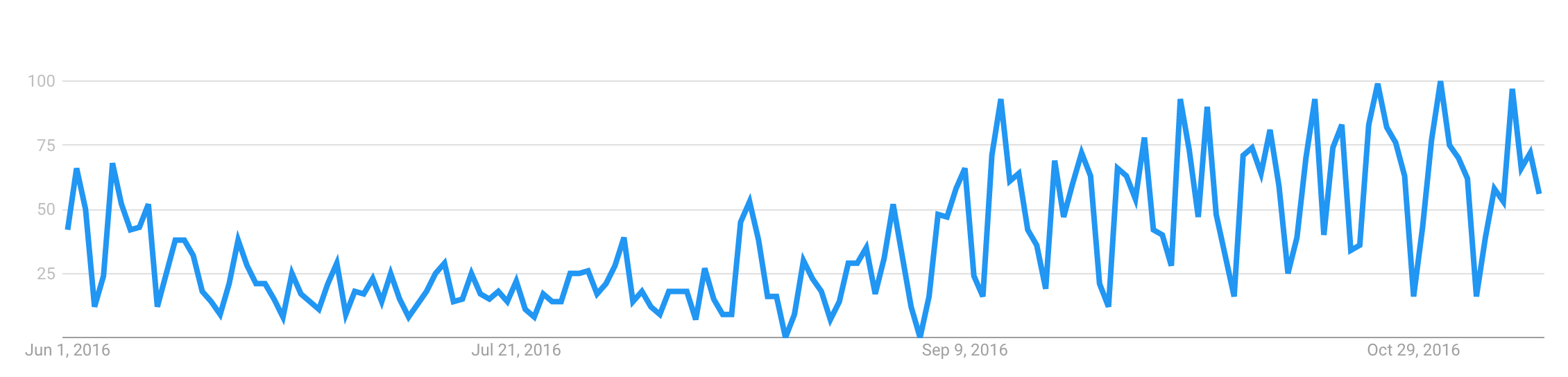

I first stratified the population of hundreds of reports from the time period of June 1 to November 12, 2016 (n=693 in Nexis Uni®), at the end of elections week, separating articles using “McCarthyite” and “McCarthyism” in reference to the elections from those referencing other events. I then took a semi-random sample of 40 articles from mainstream and alternative news sources serving a mostly-US-based audience for qualitative analysis. Because the data is time series-dependent, insofar as the quantity of articles using “McCarthyism” increased, my sample needed to reflect the proportion of articles published within that time series. By using this method, I performed an analysis of the trends in the way that “McCarthyism” or “McCarthyite” was used, the inter-relations between usages, and the popularity of specific usages in reflexive, temporal, and co-constructive context. Lastly, I analyzed the Google Trends spreadsheet for “McCarthyism” to gauge the level and time of public interest and see if Google searches for the term coincided with prominent articles and events.[83]

Data analysis required a qualitative differentiation between left and right-wing sites that used the term, and how the term is deployed relative to the political orientation of the site. In this way, better understanding could be gained on whether or not the term is used in a “partisan” fashion, or if its usage is generalized across political boundaries (and whether the fusion of political opposites bears its own partisanship). Other key terms, such as “Russia” and “collusion,” as well as “liberal,” point us toward a qualitative comprehension of the purpose for the term “McCarthyite.” In sum, this approach, which assesses the influence of given articles while qualitatively discerning their political positionality, brings us to a closer understanding of the evolution of the deployment of the term “McCarthyite,” and the dynamics of political relations comprising the ideology of Trumpism and its opponents.

In short, I observed the usage of the term “McCarthyism” across different political platforms to understand the extent to which usage overlapped in terms of rhetoric, as well as deliberate cross-over (e.g., an interview of WikiLeaks’s Julian Assange on FOX News reposted on Sputnik News). The driver for the discourse of McCarthyism seems to have been Kremlin-sympathetic media networks, some of which actively engage with Kremlin oriented soft-power organizations. However the phenomena became widespread very rapidly as key influencers adopted and endorsed it. Hence, while decrying “McCarthyism” and conflating Russia with the left, a number of actors engaging in accusations of “McCarthyism” participated in a syncretic network with critical nodes in Russian media itself. This should not be surprising, since those involved in pro-Russia groups might level accusations to defend against people criticizing Russian interference. It follows that the claims of Russian interference have been supported by available evidence, so the accusations were often deceptive and functionally part of a broader disinformation campaign around the hacks and dissemination thereof that included conspiracy theories around murdered Clinton campaign staffer Seth Rich.

Allegations of “McCarthyism”

July 2016 was a busy month for the Clinton campaign as it geared up for the Democratic National Convention. On Friday, July 22, WikiLeaks released nearly 20,000 emails leaked from seven different accounts of high-level DNC officials like Communications Director Luis Miranda and Finance Chief of Staff Scott Comer. At least some of the leaks came from a hacker who went by the name “Guccifer 2.0,” allegedly a GRU cutout, but Assange denied that Guccifer or any other Russian source had provided the leaks, implying that they may have come from Seth Rich, a deceased DNC worker, while simultaneously stating that as a matter of policy WikiLeaks never disclosed the sources of leaks.[84] The salacious contents of the emails would preclude any party unity, as Sanders supporters grew outraged over emails that showed that the DNC unjustly favored the Clinton’s campaign.

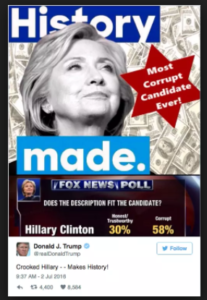

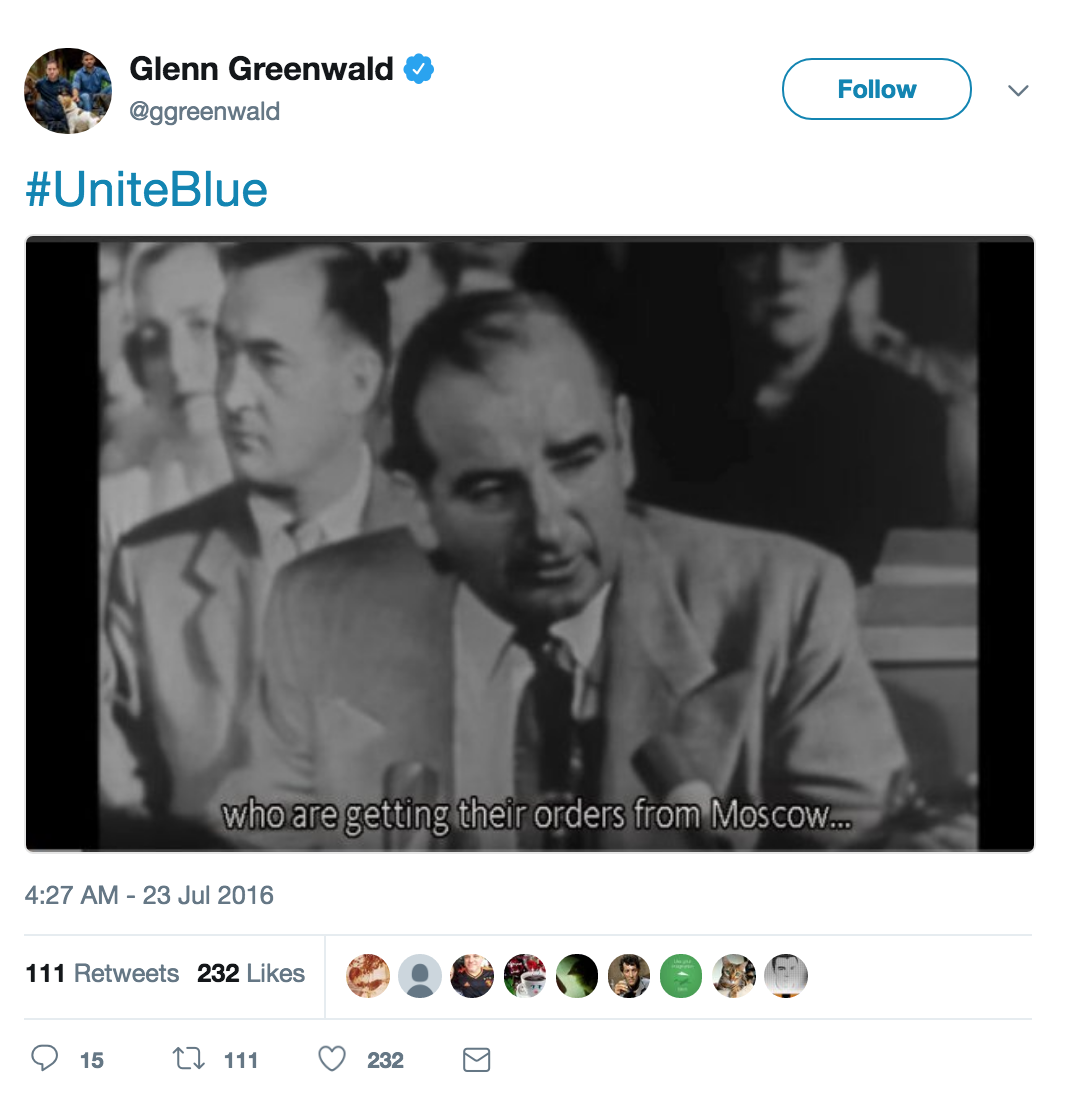

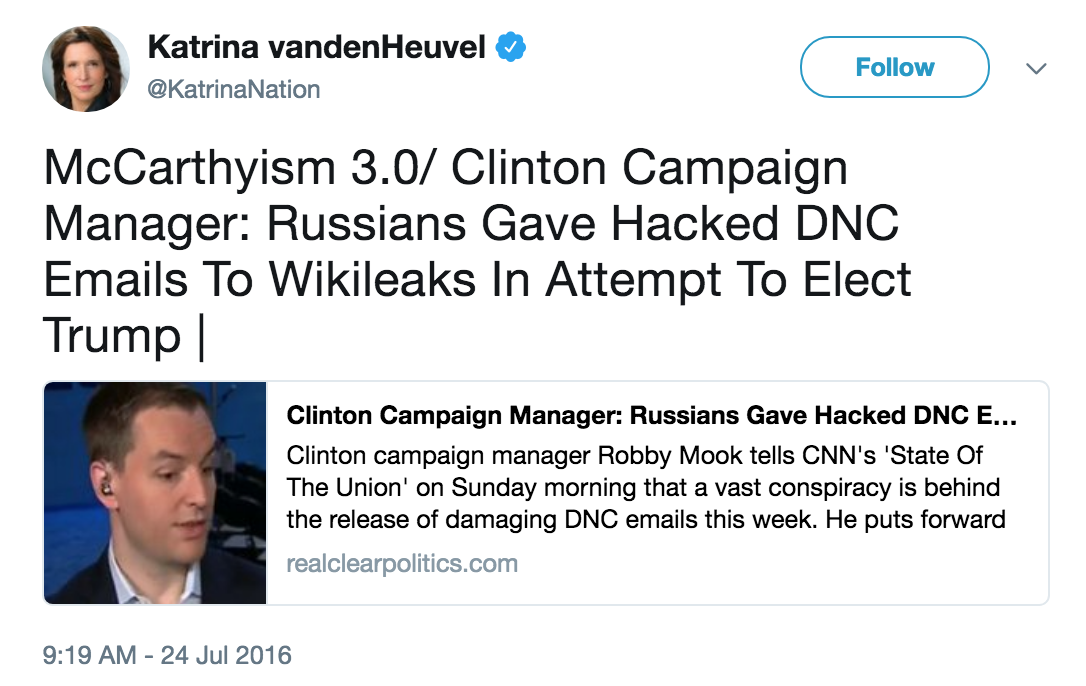

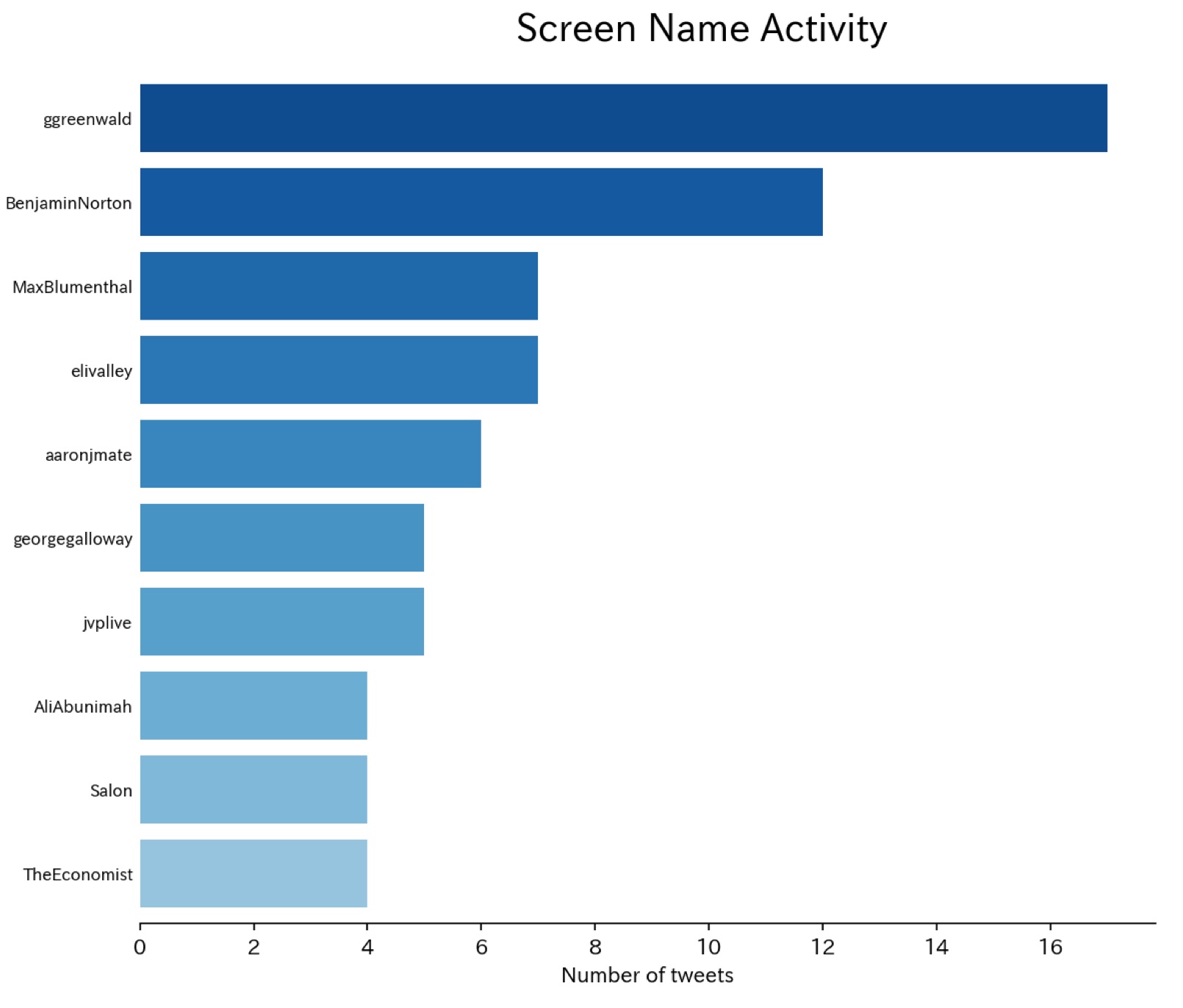

The day after the leaks, Clinton’s campaign manager Robby Mook told CNN that they believed that Russia had hacked the DNC’s accounts and sent the emails to WikiLeaks, who timed the release to help the Trump campaign. Many enraged Sanders supporters rejected the implications. As the Democrats went into their Convention, they were more disunited than ever, with embittered Sanders supporters attacking the notion of Russian intervention as a distraction from the DNC’s sabotage of the left. After Mook’s appearance, journalist Glenn Greenwald tweeted an image of Joseph McCarthy with the hashtag “UniteBlue” (Figure 4). The next day, June 24, ACEWA participant and then-editor and publisher of The Nation, Katrina vanden Heuvel, tweeted a RealClearPolitics article about Mook, adding the commentary: “McCarthyism 3.0/ Clinton Campaign Manager: Russians Gave Hacked DNC Emails to WikiLeaks In Attempt To Elect Trump” (Figure 5). The Nation’s editorial, “Against Neo-McCarthyism,” came three days later.[85] Between July 17 to 24, Google Trends shows a sharp increase of searches for the word “McCarthyite.” The term “McCarthyism” began to rise at this time and did not peak until election week, after which it dropped off considerably before rising even higher in January 2017.[86]

Trump continued to gaslight the Clinton campaign, at once denying Russian involvement and enjoining Russian hackers, “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing.”[87] That Saturday, Stephen F. Cohen of the ACEWA appeared on CNN, responding to claims that Putin might have hacked the DNC emails by insisting, “Vladimir Putin wants to end the ‘New Cold War’—and so do I.”[88] Vanden Heuvel further elaborate her position in an article published in the Washington Post the following Tuesday, declaring that the Democrats “are on the verge of becoming the Cold War party, with Trump, ironically, becoming the candidate of détente.”[89] Cohen joined conservative radio host John Batchelor for an interview published the next day titled, “Cold War, Détente, Neo-McCarthyism, and Donald Trump,” in which he claimed that Trump displays a “clearer advocacy for détente.”[90] In the meantime, nominally left-wing CounterPunch’s editor, Jeffrey St. Clair, similarly decried “the new McCarthyism,” and Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting argued that Clinton’s approach “serves to stoke Cold War panic with Russia.”[91]

Writing for Jared Kushner’s former magazine, the Observer, an activist declared that “what Robby Mook did is pure McCarthyism.”[92] In the week and a half after the July 22 WikiLeaks release, the split in the Democratic Party between Clinton supporters and Sanders supporters had become irreconcilable, with the party’s left flank insisting that “Russiagate” was a McCarthyite distraction from the failures of Clinton’s global outlook—an opinion that fed into earlier expressions of support for Trump over Clinton.

It should be recalled that, during this time, “Russiagate” referred almost exclusively to the since-proven claim that Russian intelligence was responsible for hacking the DNC and using WikiLeaks as a conduit for the dissemination of hacked emails. It should further be noted that the rise of the “McCarthyite” narrative appears to have begun with Greenwald, who openly aspires to boost the image of Russia in the US, and The Nation, which is directly connected to the ACEWA—The Nation’s Publisher/Editor, vanden Heuvel, and Stephen F. Cohen, contributing editor to The Nation and ACEWA co-founder, are married.[93] It is sufficient to say that their fiery rejection of Russian meddling afforded cover for ongoing Russian active measures, whether or not they provided that cover deliberately.

Similarly distressing instances have occurred with regards to other media disinformation campaigns, including the downing of flight MH17 and Assad’s use of chemical weapons. In these cases, Russian media has joined the fray after autonomous media networks have promoted different theories absolving Russia and Assad of crimes.[94] By promoting these seemingly-autonomous channels, the Russian vertikal appears merely to be supporting the syncretic pro-Russia media network’s critique of its own government, while actually drawing from actors with whom it is connected. As well, the vertikal functions like a “nested hierarchy” in a market-like system, identifying favored theorists, rewarding them with media attention, and outsourcing regime propaganda.

“McCarthyite” Hits the Mainstream

On August 2, the LA Times featured an editorial from Justin Raimondo, an editorial director for the libertarian site Antiwar.com, calling the suggestion of Russian intervention, “the sort of McCarthyism that we haven’t seen in this country since the most frigid years of the Cold War.”[95] Antiwar.com draws 128,067 unique visitors per month, many of whom click over from Consortium News and Pat Buchanan’s far-right website, American Conservative, according to my 2018 Alexa Audience Overlap Tool search. Among its overlapping websites are the usual suspects, including The Unz Review, which hosts the openly antisemitic Da Russophile blog by Lozansky’s think-tank participant, Anatoly Karlin.[96]

By August, websites had shifted the “McCarthyite” accusation from accusations of Russian hacking to claims that the Trump campaign might have been involved in, or known about, hacking the DNC server (the latter also being true, according to the Mueller report).[97] Following Raimondo’s editorial, Sputnik News posted two articles in quick succession on “the Clinton campaign’s rush into the comforting arms of McCarthyism” and how “the Clinton camp is obviously following in Joseph McCarthy’s footsteps.”[98] On August 9, Consortium News founder Robert Parry decried “Hillary Clinton’s Turn to McCarthyism,” and the fever pitch only increased as the campaign continued.[99]

Continuing the gaslighting of the Clinton campaign, on August 8, long-time Trump consiglieri Roger Stone admitted to communicating with WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. A few days later, he exchanged public tweets with Guccifer 2.0, thanking them, and then engaged in private communications with the account over a couple of weeks. [100] Regardless of Stone’s open flirtations with a cutout for the GRU and WikiLeaks, which disseminated its hacked data, the Trump campaign denied any insinuation of contact with Russian agencies or political operatives (a denial later proven false).[101]

In mid-August, RT ran a five-minute piece titled “Parallels Drawn Between Clinton Campaign and McCarthy’s Witch-Hunt” featuring former CIA officer Philip Giraldi, a leading figure in the syncretic media ecosystem with bylines in all of the horizontal media sites studied in relation to Lozansky’s think tank.[102] On August 21, Sputnik announced “the resurgence of Cold War style McCarthyism and anti-Russian propaganda,” followed the next day by Huffington Post, which stressed the dangers of “Clinton’s present-day McCarthyism.”[103] The World Socialist Web Site extended the analysis the next day, attacking the New York Times for “outright lies in a manner reminiscent of McCarthyism.” By this point, as we see with Huffington Post, the “McCarthyite” narrative had become generalized and mainstream.

Two days later Julian Assange gave a widely-viewed interview to Megyn Kelly of FOX News, insisting that Clinton has “grabbed on the neo-McCarthyism hysteria about Russia and has been using it to demonize the Trump campaign.”[104] Sputnik International and RT both publicized the interview through their networks, and RT published an article the following Sunday criticizing Clinton for “Russophobia.”[105] That Tuesday, Antiwar.com published “The Campaign to Blame Putin for Everything,” excoriating “the historically Russophobic Clintons,” and the next day, August 31, Glenn Greenwald went on Democracy Now to denounce linking WikiLeaks with Russia as “a new McCarthyism.”[106] That same day, the New York Times published an interview with Julian Assange in which he accused the newspaper of “erecting a demon” by supporting Clinton.[107] Nevertheless, the Mueller report later confirmed WikiLeaks likely received stolen emails from the GRU through an encrypted file sent via email, a fact which few of the advocates of the “McCarthyite” narrative have reflected on, much less been able to convincingly rebut.[108]

The day after Greenwald’s interview with Democracy Now, the Observer criticized “an insurgence of neo-McCarthyism, alleging that the Trump campaign has ties to the Russian government,” and RT interviewed left-wing commentator Mike Papantonio, who called the question of Russian intervention “crazy, radical talk,” “all supposition” intended to distract from the content of the emails.[109] Two days after Papantonio’s interview, on September 3, RT turned on the left, inquiring into a “McCarthyism of the left?”[110] The following Wednesday, September 6, Breitbart was mocking “Hillary Clinton’s Absurd, McCarthyist Russian Conspiracy Theory” from their headlines, followed the next day by Consortium News’s scathing piece, “New York Times and the New McCarthyism.”[111] The period from September 4-11 saw an interesting rise in searches for “McCarthyite” according to Google Trends. Daniel McAdams of the Ron Paul Center tweeted on September 26 that Clinton’s claim that “Putin is hacking us” was an “insane conspiracy theory.”[112]

The frequency with which alternative news sites published articles denouncing the “mainstream media” for McCarthyism, as well as their crossover in terms both of audience and journalists, is fascinating for a number of reasons. Perhaps paramount among those is the inability to explain the hacked emails. Some sites turned to conspiracy theories surrounding Seth Rich, a former DNC employee who had been tragically murdered; further investigation was unable to demonstrate that Rich or his murder had anything to do with the leaks, and Rich’s parents currently have an ongoing lawsuit against FOX News and two of its commentators for its unsubstantiated allegations about Rich.[113] Another interesting facet of the research thus far is the repudiation of “mainstream media” in and even to the mainstream media, as with vanden Heuvel’s editorial in the Washington Post, Raimondo’s editorial in the LA Times, and Assange’s interview in the New York Times. Similarly important was the convergence of left-wing repudiations with far-right media like Breitbart lambasting the “mainstream” media and left-wing McCarthyism, even amid high site ratings and campaigns to oust left-wing professors from universities.

It is important to note that, at this point, not only had the term “McCarthyite” become diffuse but its narrative had also slipped into different meanings and contexts. The accusation that began with a denial of Russian hacking now involved general “Russophobia” and especially the idea that Trump was collaborating with the Russian government. Generally, the hysteria and anxiety surrounding the accusations of “collusion” were easily matched, if not exceeded, by the accusations of “McCarthyism” against those who correctly assigned blame for the email releases to Russian hackers disseminating through WikiLeaks. Again, it is important to stress that evidence does not necessarily show that the “McCarthyite” spin was centrally planned or conspired by the Kremlin, but that (1) it was propagated first by individuals like Cohen, Greenwald, and vanden Heuvel who have directly involved themselves in promoting Russia’s image, and (2) the Russian vertikal eagerly exploited it on behalf of a disinformation campaign in support of Trump’s campaign.

Just days after the articles from Breitbart and Consortium, a Washington Post-ABC News poll showed that the negative spin surrounding the revelations around Russian meddling resulted in a tightening race with ominous signs for the Clinton campaign.[114] While nearly 100% of Trump’s supporters insisted they would vote, only 80% of Clinton’s said the same, and only a third of her supporters claimed to be enthusiastic. As Jeff Greenfield wrote in Politico, “constituencies most critical to her campaign seem to have no sense of urgency about keeping Donald Trump out of the White House.”[115] Of course, other elements contributed to the disenfranchisement of Clinton’s base, as well; however, after each debate, Clinton came out the victor, suggesting that her policies and approach appealed to more voters who participated in CNN/ORC polls.[116] As others have argued, the release of the hacked emails, the proliferation of disinformation, and the later, associated FBI announcement regarding Clinton’s use of a private email server, contributed to the decline in her popularity between and after the debates but was not necessarily decisive.[117]

Importantly, many of those disillusioned with Clinton could be found among the Democratic Party’s base of non-white supporters actively targeted by disinformation.[118] Amid controversy over her comments on “super-predators” during the 1990s and the legacy of mass incarceration, as well as disillusionment with the Democrats’ handling of the Black Lives Matter movement, Black Agenda Report declared that “the Clinton campaign has ignited a neo-McCarthyist war on Russia and anyone who stands in the way of her agenda.”[119] Meanwhile, Sputnik continued its onslaught with headlines like, “When Hillary Clinton Gets Scared She Plays the Russia Card,” making an allusion that connected criticism of Russian interference to the “race card.”[120] Furthermore, it is now understood from millions of published tweets pushed out of the Internet Research Agency at the time, that Kremlin-controlled bot and troll accounts on social media used racial divisions to turn discontent and disenfranchisement against liberalism.[121]

The Elections and Aftermath

Clinton’s bad September turned into a terrible October when, on October 9, WikiLeaks produced a new bevy of emails from Podesta’s email account, leading to a deluge of fiery illiberalism throughout the syncretic ecosystem. That evening, Trump proclaimed, “I love WikiLeaks!” at a rally. Two days later, WikiLeaks wrote Trump, Jr., “Hey Donald, great to see you and your dad talking about our publications. Strongly suggest your dad tweets this link if he mentions us… Btw we just released Podesta Emails Part 4.” In an apparent exposition of collaboration, Trump, Jr., tweeted in support of Wikileaks two hours later, lamenting the “Rigged system!” and two days later tweeted out their link.[122] That same day, Roger Stone publicly denied collusion with WikiLeaks as “categorically false,” insisting that his relationship with Assange was only through a “mutual friend,” but that he had “a back-channel communications with WikiLeaks.”[123] He would later be convicted of lying to Congress and witness tampering in efforts to obstruct federal investigators’ inquiry into the hacked emails and Russian interference in the elections.[124]

The week of October 9-16 saw the sharpest rise of Google searches for “McCarthyite” in the study period, indicating that, as the emails were released, more accusations of Russian meddling emerged, and activists responded with accusations of “McCarthyism.” As the weeks closed in on the November 7 election day, the flurry of articles cautioning against McCarthyism and Russophobia increased apace. From Counterpunch on Oct 18, left-wing organizer Srećko Horvat denounced the Clinton camp’s “‘soft’ McCarthyism,” while a Sputnik writer capitalized on the trends, lamenting that he was “The first victim of McCarthyism 2.0.”[125] The next day, Roger Stone was quoted in Breitbart as saying, “this is the new McCarthyism.”[126] At the same time, Consortium News ridiculed “The Democrats’ Joe McCarthy Moment” and nominally left-wing AlterNet blogger Ben Norton tweeted about Clinton’s claim that WikiLeaks received the emails from Russian intelligence, “McCarthyism is alive and well.”[127]

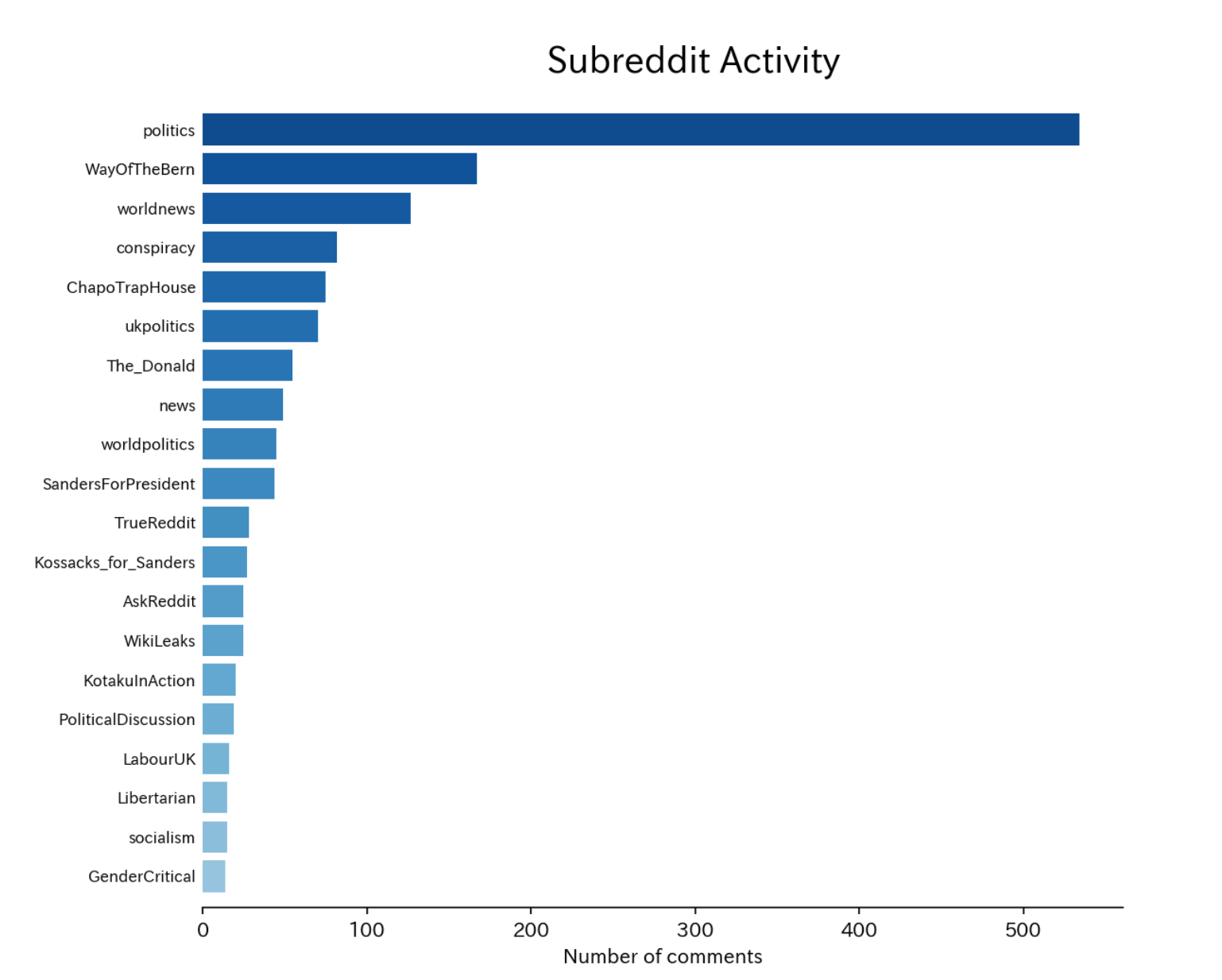

On RT on October 23, anti-imperialist commentator Daniel Patrick Welch declared, “Clinton [is] using anti-Russia red-baiting not seen since days of McCarthyism,” followed the next day by Consortium News’s recap of the Russian response to the recent debate in which Doctorow declared, “The main theme of American political life right now is McCarthyism and anti-Russian hysteria.”[128] Antiwar.com ran their piece, “’McCarthyism,’ Then and Now,” the following day, and three days later, on October 28, CounterPunch likened the charges of Russian interference to “the paranoia that accompanied the Red Scare in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution and then reappeared with greater intensity in the form of McCarthyism.”[129] The Observer declared that “McCarthyism 2.0 Has Infected the Democrats” on November 1, with Sputnik insisting, “Washington Fails to Prove Russia Interfered in US Elections in ‘Big Way.’”[130] Pro-Palestine blog MondoWeiss quoted Carden of the ACEWA decrying “a very very ugly echo of McCarthyism” three days later, and then the day before the election, left-wing site Jacobin stated that, “to distract attention from the content of the emails, the Democrats have engaged in a modern-day version of McCarthyism.”[131] Again, the inclusion of sites like Jacobin and Huffington Post only further illustrates how widely the campaign to identify Russia’s hacking of the DNC as “McCarthyism” had spread throughout the alternative media ecosystem well beyond Russia’s apparent direct influence.