a review of Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2014)

~

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century has succeeded both commercially and as a work of scholarship. Capital‘s empirical research is widely praised among economists—even by those who disagree with its policy prescriptions. It is also the best-selling book in the century-long history of Harvard University Press, and a rare work of scholarship to reach the top spot on Amazon sales rankings.[1]

Capital‘s main methodological contribution is to bring economic, sociological, and even literary perspectives to bear in a work of economics.[2] The book bridges positive and normative social science, offering strong policy recommendations for increased taxation of the wealthiest. It is also an exploration of historical trends.[3] In Capital, fifteen years of careful archival research culminate in a striking thesis: capitalism exacerbates inequality over time. There is no natural tendency for markets themselves, or even ordinary politics, to slow accumulation by top earners.[4]

This review explains Piketty’s analysis and its relevance to law and social theory, drawing lessons for the re-emerging field of political economy. Piketty’s focus on long-term trends in inequality suggests that many problems traditionally explained as sector-specific (such as varied educational outcomes) are epiphenomenal with regard to increasingly unequal access to income and capital. Nor will a narrowing of purported “skills gaps” do much to improve economic security, since opportunity to earn money via labor matters far less in a world where capital is the key to enduring purchasing power. Policymakers and attorneys ignore Piketty at their peril, lest isolated projects of reform end up as little more than rearranging deck chairs amidst titanically unequal opportunities.

Inequality, Opportunity, and the Rigged Game

Capital weaves together description and prescription, facts and values, economics, politics, and history, with an assured and graceful touch. So clear is Piketty’s reasoning, and so compelling the enormous data apparatus he brings to bear, that few can doubt he has fundamentally altered our appreciation of the scope, duration, and intensity of inequality.[5]

Piketty’s basic finding is that, absent extraordinary political interventions, the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of growth of the economy generally (g), which Piketty expresses via the now-famous formula r > g.[6] He finds that this relationship persists over time, and in the many countries with reliable data on wealth and income.[7] This simple inequality relationship has many troubling implications, especially in light of historical conflicts between capital and labor.

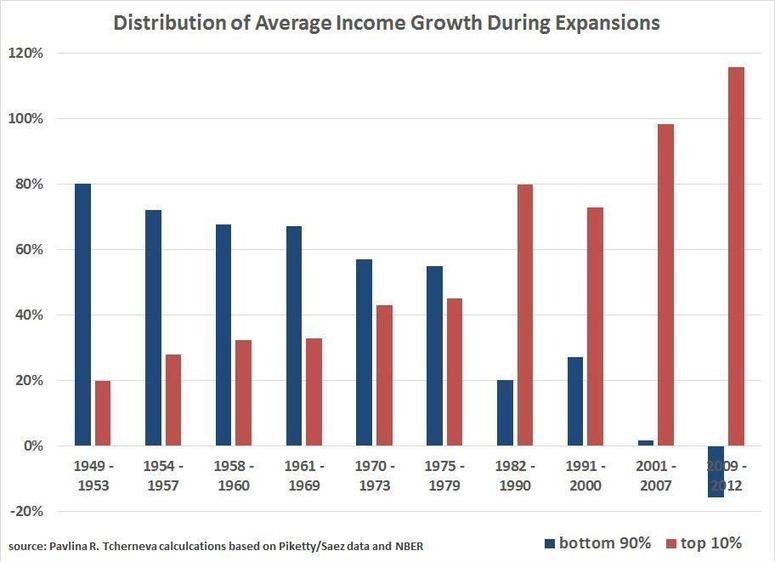

Most persons support themselves primarily by wages—that is, what they earn from their labor. As capital takes more of economic output (an implication of r > g persisting over time), less is left for labor. Thus if we are concerned about unequal incomes and living standards, we cannot simply hope for a rising tide of growth to lift the fortunes of those in the bottom quintiles of the income and wealth distribution. As capital concentrates, its owners take an ever larger share of income—unless law intervenes and demands some form of redistribution.[8] As the chart below (by Bard economist Pavlina Tcherneva, based on Piketty’s data) shows, we have now reached the point where the US economy is not simply distributing the lion’s share of economic gains to top earners; it is actively redistributing extant income of lower decile earners upwards:

In 2011, 93% of the gains in income during the economic “recovery” went to the top 1%. From 2009 to 2011, “income gains to the top 1% … were 121% of all income increases,” because “incomes to the bottom 99% fell by 0.4%.”[9] The trend continued through 2012.

Fractal inequality prevails up and down the income scale.[10] The top 15,000 tax returns in the US reported an average taxable income of $26 million in 2005—at least 400 times greater than the median return.[11] Moreover, Larry Bartels’s book, Unequal Democracy, graphs these trends over decades.[12] Bartels shows that, from 1945-2007, the 95th percentile did much better than those at lower percentiles.[13] He then shows how those at the 99.99th percentile did spectacularly better than those at the 99.9th, 99.5th, 99th, and 95th percentiles.[14] There is some evidence that even within that top 99.99th percentile, inequality reigned. In 2005, the “Fortunate 400″—the 400 households with the highest earnings in the U.S.—made on average $213.9 million apiece, and the cutoff for entry into this group was a $100 million income—about four times the average income of $26 million prevailing in the top 15,000 returns.[15] As Danny Dorling observed in a recent presentation at the RSA, for those at the bottom of the 1%, it can feel increasingly difficult to “keep up with the Joneses,” Adelsons, and Waltons. Runaway incomes at the very top leave those slightly below the “ultra-high net worth individual” (UHNWI) cut-off ill-inclined to spread their own wealth to the 99%.

Thus inequality was well-documented in these, and many other works, by the time Piketty published Capital—indeed, other authors often relied on the interim reports released by Piketty and his team of fellow inequality researchers over the past two decades.[16] The great contribution of Capital is to vastly expand the scope of the inquiry, over space and time. The book examines records in France going back to the 19th century, and decades of data in Germany, Japan, Great Britain, Sweden, India, China, Portugal, Spain, Argentina, Switzerland, and the United States.[17]

The results are strikingly similar. The concentration of capital (any asset that generates income or gains in monetary value) is a natural concomitant of economic growth under capitalism—and tends to intensify if growth slows or stops.[18] Inherited fortunes become more important than those earned via labor, since the “miracle of compound interest” overwhelms any particularly hard-working person or ingenious idea. Once fortunes grow large enough, their owners can simply live off the interest and dividends they generate, without ever drawing on the principal. At the “escape velocity” enjoyed by some foundations and ultra-rich individuals, annual expenses are far less than annual income, precipitating ever-greater principal. This is Warren Buffett’s classic “snowball” of wealth—and we should not underestimate its ability to purchase the political favors that help constitute Buffettian “moats” around the businesses favored by the likes of Berkshire-Hathaway.[19] Dynasties form and entrench their power. If they can make capital pricey enough, even extraordinary innovations may primarily benefit their financers.

Deepening the Social Science of Political Economy

Just as John Rawls’s Theory of Justice laid a foundation for decades of writing on social justice, Piketty’s work is so generative that one could envision whole social scientific fields revitalized by it.[20] Political economy is the most promising, a long tradition of (as Piketty puts it) studying the “ideal role of the state in the economic and social organization of a country.”[21] Integrating the long-divided fields of politics and economics, a renewal of modern political economy could unravel “wicked problems” neither states nor markets alone can address.[22]

But the emphasis in Piketty’s definition of political economy on “a country,” versus countries, or the world, is in tension with the global solutions he recommends for the regulation of capital. The dream of neoliberal globalization was to unite the world via markets.[23] Anti-globalization activists have often advanced a rival vision of local self-determination, predicated on overlaps between political and economic boundaries. State-bound political economy could theorize those units. But the global economy is, at present, unforgiving of autarchy and unlikely to move towards it.

Capital tends to slip the bonds of states, migrating to tax havens. In the rarefied world of the global super-rich, financial privacy is a purchasable commodity. Certainly there are always risks of discovery, or being taken advantage of by a disreputable tax shelter broker or shady foreign bank. But for many wealthy individuals, tax havenry has been a rite of passage on the way to membership in a shadowy global elite. Piketty’s proposed global wealth tax would need international enforcement—for even the Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) imposed via America’s fading hegemony (and praised by Piketty) has only begun to address the problem of hidden (or runaway) wealth (and income).[24]

It will be very difficult to track down the world’s hidden fortunes and tax them properly. Had Piketty consulted more legal sources, he may have acknowledged the problem more adequately in Capital. He recommends “automatic information exchange” among tax authorities, which is an excellent principle to improve enforcement. But actually implementing this principle could require fine-grained regulation of IT systems, deployment of whole new types of surveillance, and even uniform coding (via, say, standard legal entity identifiers, or LEIs) globally. More frankly acknowledging the difficulty of shepherding such legislation globally could have led to a more convincing (and comprehensive) examination of the shortcomings of globalized capitalism.

In several extended interviews on Capital (with CNN Money, Econtalk, The New York Times, Huffington Post, and the New Republic, among others), Piketty pledges fealty to markets, praising their power to promote production and innovation. Never using the term “industrial policy” in his book, Piketty hopes that law may make the bounty of extant economic arrangements accessible to all, rather than changing the nature of those arrangements. But we need to begin to ask whether our very process of creating goods and services itself impedes better distribution of them.

Unfortunately, mainstream economics itself often occludes this fundamental question. When distributive concerns arise, policymakers can either substantively intervene to reshape the benefits and burdens of commerce (a strategy economists tend to derogate as dirigisme), or may, post hoc, use taxes and transfer programs to redistribute income and wealth. For establishment economists, redistribution (happening after initial allocations by “the market”) is almost always considered more efficient than “distortion” of markets by regulation, public provision, or “predistribution.”[25]

Tax law has historically been our primary way of arranging such redistribution, and Piketty makes it a focus of the concluding part of his book, called “Regulating Capital.” Piketty laments the current state of tax reporting and enforcement. Very wealthy individuals have developed complex webs of shell entities to hide their true wealth and earnings.[26] As one journalist observed, “Behind a New York City deed, there may be a Delaware LLC, which may be managed by a shell company in the British Virgin Islands, which may be owned by a trust in the Isle of Man, which may have a bank account in Liechtenstein managed by the private banker in Geneva. The true owner behind the structure might be known only to the banker.”[27] This is the dark side of globalization: the hidden structures that shield the unscrupulous from accountability.[28]

The most fundamental tool of tax secrecy is separation: between persons and their money, between corporations and the persons who control them, between beneficial and nominal controllers of wealth. When money can pass between countries as easily as digital files, skilled lawyers and accountants can make it impossible for tax authorities to uncover the beneficial owners of assets (and the income streams generated by those assets).

Piketty believes that one way to address inequality is strict enforcement of laws like America’s FATCA.[29] But the United States cannot accomplish much without pervasive global cooperation. Thus the international challenge of inequality haunts Capital. As money concentrates in an ever smaller global “superclass” (to use David J. Rothkopf’s term), it’s easier for it to escape any ruling authority.[30] John Chung has characterized today’s extraordinary concentrations of wealth as a “death of reference” in our monetary system and its replacement with “a total relativity.”[31] He notes that “[i]n 2007, the average amount of annual compensation for the top twenty-five highest paid hedge fund managers was $892 million;” in the past few years, individual annual incomes in the group have reached two, three, or four billion dollars. Today’s greatest hoards of wealth are digitized, as easily moved and hidden as digital files.

We have no idea what taxes may be due from trillions of dollars in offshore wealth, or to what purposes it is directed.[32] In less-developed countries, dictators and oligarchs smuggle ill-gotten gains abroad. Groups like Global Financial Integrity and the Tax Justice Network estimate that illicit financial flows out of poor countries (and into richer ones, often via tax havens) are ten times greater than the total sum of all development aid—nearly $1 trillion per year. Given that the total elimination of extreme global poverty could cost about $175 billion per year for twenty years, this is not a trivial loss of funds—completely apart from what the developing world loses in the way of investment when its wealthiest residents opt to stash cash in secrecy jurisdictions.[33]

An adviser to the Tax Justice Network once said that assessing money kept offshore is an “exercise in night vision,” like trying to measure “the economic equivalent of an astrophysical black hole.”[34] Shell corporations can hide connections between persons and their money, between corporations and the persons who control them, between beneficial and nominal owners. When enforcers in one country try to connect all these dots, there is usually another secrecy jurisdiction willing to take in the assets of the conniving. As the Tax Justice Network’s “TaxCast” exposes on an almost monthly basis, victories for tax enforcement in one developed country tend to be counterbalanced by a slide away from transparency elsewhere.

Thus when Piketty recommends that “the only way to obtain tangible results is to impose automatic sanctions not only on banks but also on countries that refuse to require their financial institutions” to report on wealth and income to proper taxing authorities, one has to wonder: what super-institution will impose the penalties? Is this to be an ancillary function of the WTO?[35] Similarly, equating the imposition of a tax on capital with “the stroke of a pen” (568) underestimates the complexity of implementing such a tax, and the predictable forms of resistance that the wealth defense industry will engage in.[36] All manner of societal and cultural, public and private, institutions will need to entrench such a tax if it is to be a stable corrective to the juggernaut of r > g.[37]

Given how much else the book accomplishes, this demand may strike some as a cavil—something better accomplished by Piketty’s next work, or by an altogether different set of allied social scientists. But if Capital itself is supposed to model (rather than merely call for) a new discipline of political economy, it needs to provide more detail about the path from here to its prescriptions. Philosophers like Thomas Pogge and Leif Wenar, and lawyers like Terry Fisher and Talha Syed, have been quite creative in thinking through the actual institutional arrangements that could lead to better distribution of health care, health research, and revenues from natural resources.[38] They are not cited in Capital¸but their work could have enriched its institutional analysis greatly.

An emerging approach to financial affairs, known as the Legal Theory of Finance (LTF), also offers illumination here, and should guide future policy interventions. Led by Columbia Law Professor Katharina Pistor, an interdisciplinary research team of social scientists and attorneys have documented the ways in which law is constitutive of so-called financial markets.[39] Revitalizing the tradition of legal realism, Pistor has demonstrated the critical role of law in generating modern finance. Though law to some extent shapes all markets, in finance, its role is most pronounced. The “products” traded are very little more than legal recognitions of obligations to buy or sell, own or owe. Their value can change utterly based on tiny changes to the bankruptcy code, SEC regulations, or myriad other laws and regulations.

The legal theory of finance changes the dialogue about regulation of wealth. The debate can now move beyond stale dichotomies like “state vs. market,” or even “law vs. technology.” While deregulationists mock the ability of regulators to “keep up with” the computational capacities of global banking networks, it is the regulators who made the rules that made the instantaneous, hidden transfer of financial assets so valuable in the first place. Such rules are not set in stone.

The legal theory of finance also enables a more substantive dialogue about the central role of law in political economy. Not just tax rules, but also patent, trade, and finance regulation need to be reformed to make the wealthy accountable for productively deploying the wealth they have either earned or taken. Legal scholars have a crucial role to play in this debate—not merely as technocrats adjusting tax rules, but as advisors on a broad range of structural reforms that could ensure the economy’s rewards better reflected the relative contributions of labor, capital, and the environment.[40] Lawyers had a much more prominent role in the Federal Reserve when it was more responsive to workers’ concerns.[41]

Imagined Critics as Unacknowledged Legislators

A book is often influenced by its author’s imagined critics. Piketty, decorous in his prose style and public appearances, strains to fit his explosive results into the narrow range of analytical tools and policy proposals that august economists won’t deem “off the wall.”[42] Rather than deeply considering the legal and institutional challenges to global tax coordination, Piketty focuses on explaining in great detail the strengths and limitations of the data he and a team of researchers have been collecting for over a decade. But a renewed social science of political economy depends on economists’ ability to expand their imagined audience of critics, to those employing qualitative methodologies, to attorneys and policy experts working inside and outside the academy, and to activists and journalists with direct knowledge of the phenomena addressed. Unfortunately, time that could have been valuably directed to that endeavor—either in writing Capital, or constructively shaping the extraordinary publicity the book received—has instead been diverted to shoring up the book’s reputation as rigorous economics, against skeptics who fault its use of data.

To his credit, Piketty has won these fights on the data mavens’ own terms. The book’s most notable critic, Chris Giles at the Financial Times, tried to undermine Capital‘s conclusions by trumping up purported ambiguities in wealth measurement. His critique was rapidly dispatched by many, including Piketty himself.[43] Indeed, as Neil Irwin observed, “Giles’s results point to a world at odds not just with Mr. Piketty’s data, but also with that by other scholars and with the intuition of anyone who has seen what townhouses in the Mayfair neighborhood of London are selling for these days.”[44]

One wonders if Giles reads his own paper. On any given day one might see extreme inequality flipping from one page to the next. For example, in a special report on “the fragile middle,” Javier Blas noted that no more than 12% of Africans earned over $10 per day in 2010—a figure that has improved little, if at all, since 1980.[45] Meanwhile, in the House & Home section on the same day, Jane Owen lovingly described the grounds of the estate of “His Grace Henry Fitzroy, the 12th Duke of Grafton.” The grounds cost £40,000 to £50,000 a year to maintain, and were never “expected to do anything other than provide pleasure.”[46] England’s revanchist aristocracy makes regular appearances in the Financial Times “How to Spend It” section as well, and no wonder: as Oxfam reported in March, 2014, Britain’s five richest families have more wealth than its twelve million poorest people.[47]

Force and Capital

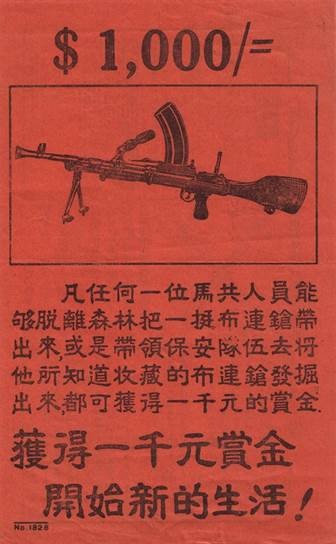

The persistence of such inequalities is as much a matter of law (and the force behind it to, say, disperse protests and selectively enforce tax regulations), as it is a natural outgrowth of the economic forces driving r and g. To his credit, Piketty does highlight some of the more grotesque deployments of force on behalf of capital. He begins Part I (“Income and Capital”) and ends Part IV (“Regulating Capital”) by evoking the tragic strike at the Lonmin Mine in South Africa in August 2012. In that confrontation, “thirty-four strikers were shot dead” for demanding pay of about $1,400 a month (there were making about $700).[48] Piketty deploys the story to dramatize conflict over the share of income going to capital versus labor. But it also illustrates dynamics of corruption. Margaret Kimberley of Black Agenda Report claims that the union involved was coopted thanks to the wealth of the man who once ran it.[49] The same dynamics shine through documentaries like Big Men (on Ghana), or the many nonfiction works on oil exploitation in Africa. [50]

Piketty observes that “foreign companies and stockholders are at least as guilty as unscrupulous African elites” in promoting the “pillage” of the continent.[51] Consider the state of Equatorial Guinea, which struck oil in 1995. By 2006, Equatoguineans had the third highest per capita income in the world, higher than many prosperous European countries.[52] Yet the typical citizen remains very poor. [53] In the middle of the oil boom, an international observer noted that “I was unable to see any improvements in the living standards of ordinary people. In 2005, nearly half of all children under five were malnourished,” and “[e]ven major cities lack[ed] clean water and basic sanitation.”[54] The government has not demonstrated that things have improved much since them, despite ample opportunity to do so. Poorly paid soldiers routinely shake people down for bribes, and the country’s president, Teodoro Obiang, has paid Moroccan mercenaries for his own protection. A 2009 book noted that tensions in the country had reached a boiling point, as the “local Bubi people of Malabo” felt “invaded” by oil interests, other regions were “abandoned,” and self-determination movements decried environmental and human rights abuses.[55]

So who did benefit from Equatorial Guinea’s oil boom? Multinational oil companies, to be sure, though we may never know exactly how much profit the country generated for them—their accounting was (and remains) opaque. The Riggs Bank in Washington, D.C. gladly handled accounts of President Obiang, as he became very wealthy. Though his salary was reported to be $60,000 a year, he had a net worth of roughly $600 million by 2011.[56] (Consider, too, that such a fortune would not even register on recent lists of the world’s 1,500 or so billionaires, and is barely more than 1/80th the wealth of a single Koch brother.) Most of the oil companies’ payments to him remain shrouded in secrecy, but a few came to light in the wake of US investigations. For example, a US Senate report blasted him for personally taking $96 million of his nation’s $130 million in oil revenue in 1998, when a majority of his subjects were malnourished.[57]

Obiang’s sordid record has provided a rare glimpse into some of the darkest corners of the global economy. But his story is only the tip of an iceberg of a much vaster shadow economy of illicit financial flows, secrecy jurisdictions, and tax evasion. Obiang could afford to be sloppy: as the head of a sovereign state whose oil reserves gave it some geopolitical significance, he knew that powerful patrons could shield him from the fate of an ordinary looter. Other members of the hectomillionaire class (and plenty of billionaires) take greater precautions. They diversify their holdings into dozens or hundreds of entities, avoiding public scrutiny with shell companies and pliant private bankers. A hidden hoard of tens of trillions of dollars has accumulated, and likely throws off hundreds of billions of dollars yearly in untaxed interest, dividends, and other returns.[58] This drives a wedge between a closed-circuit economy of extreme wealth and the ordinary patterns of exchange of the world’s less fortunate.[59]

The Chinese writer and Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo once observed that corruption in Beijing had led to an officialization of the criminal and the criminalization of the official.[60] Persisting even in a world of brutal want and austerity-induced suffering, tax havenry epitomizes that sinister merger, and Piketty might have sharpened his critique further by focusing on this merger of politics and economics, of private gain and public governance. Authorities promote activities that would have once been proscribed; those who stand in the way of such “progress” might be jailed (or worse). In Obiang’s Equatorial Guinea, we see similar dynamics, as the country’s leader extracts wealth at a volume that could only be dreamed of by a band of thieves.

Obiang’s curiously double position, as Equatorial Guinea’s chief law maker and law breaker, reflects a deep reality of the global shadow economy. And just as “shadow banks” are rivalling more regulated banks in terms of size and influence, shadow economy tactics are starting to overtake old standards. Tax avoidance techniques that were once condemned are becoming increasingly acceptable. Campaigners like UK Uncut and the Tax Justice Network try to shame corporations for opportunistically allocating profits to low-tax jurisdictions.[61] But CEOs still brag about their corporate tax unit as a profit center.

When some of Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s recherché tax strategies were revealed in 2012, Barack Obama needled him repeatedly. The charges scarcely stuck, as Romney’s core constituencies aimed to emulate rather than punish their standard-bearer.[62] Obama then appointed a Treasury Secretary (Jack Lew), who had himself utilized a Cayman Islands account. Lew was the second Obama Treasury secretary to suffer tax troubles: Tim Geithner, his predecessor, was also accused of “forgetting” to pay certain taxes in a self-serving way. And Obama’s billionaire Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker was no stranger to complex tax avoidance strategies.[63]

Tax attorneys may characterize Pritzker, Lew, Geithner, and Romney as different in kind from Obiang. But any such distinctions they make will likely need to be moral, rather than legal, in nature. Sure, these American elites operated within American law—but Obiang is the law of Equatorial Guinea, and could easily arrange for an administrative agency to bless his past actions (even developed legal systems permit retroactive rulemaking) or ensure the legality of all future actions (via safe harbors). The mere fact that a tax avoidance scheme is “legal” should not count for much morally—particularly as those who gain from prior US tax tweaks use their fortunes to support the political candidacies of those who would further push the law in their favor.

Shadowy financial flows exemplify the porous boundary between state and market. The book Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works argues that the line between savvy tax avoidance and illegal tax evasion (or strategic money transfers and forbidden money laundering) is blurring.[64] Between our stereotypical mental images of dishonest tycoons sipping margaritas under the palm trees of a Caribbean tax haven, and a state governor luring a firm by granting it a temporary tax abatement, lie hundreds of subtler scenarios. Dingy rows of Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming file cabinets can often accomplish the same purpose as incorporating in Belize or Panama: hiding the real beneficiaries of economic activity.[65] And as one wag put it to journalist Nicholas Shaxson, “the most important tax haven in the world is an island”—”Manhattan.”[66]

In a world where “tax competition” is a key to neoliberal globalization, it is hard to see how a global wealth tax (even if set at the very low levels Piketty proposes) supports (rather than directly attacks) existing market order. Political elites are racing to reduce tax liability to curry favor with the wealthy companies and individuals they hope to lure, serve, and bill. The ultimate logic of that competition is a world made over in the image of Obiang’s Equatorial Guinea: crumbling infrastructure and impoverished citizenries coexisting with extreme luxury for a global extractive elite and its local enablers. Books like Third World America, Oligarchy, and Captive Audience have already started chronicling the failure of the US tax system to fund roads, bridges, universal broadband internet connectivity, and disaster preparation.[67] As tax avoiding elites parley their gains into lobbying for rules that make tax avoidance even easier, self-reinforcing inequality seems all but inevitable. Wealthy interests can simply fund campaigns to reduce their taxes, or to reduce the risk of enforcement to a nullity. As Ben Kunkel pointedly asks, “How are the executive committees of the ruling class in countries across the world to act in concert to impose Piketty’s tax on just this class?”[68]

US history is instructive here. Congress passed a tax on the top 0.1% of earners in 1894, only to see the Supreme Court strike the tax down in a five to four decision. After the 16th Amendment effectively repealed that Supreme Court decision, Congress steadily increased the tax on high income households. From 1915 to 1918, the highest rate went from 7% to 77%, and over fifty-six tax brackets were set. When high taxes were maintained for the wealthy after the war, tax evasion flourished. At this point, as Jeffrey Winters writes, the government had to choose whether to “beef up law enforcement against oligarchs … , or abandon the effort and instead squeeze the same resources from citizens with far less material clout to fight back.”[69] Enforcement ebbed and flowed. But since then, what began by targeting the very wealthy has grown to include “a mass tax that burdens oligarchs at the same effective rate as their office staff and landscapers.”[70]

The undertaxation of America’s wealthy has helped them capture key political processes, and in turn demand even less taxation. The dynamic of circularity teaches us that there is no stable, static equilibrium to be achieved between regulators and regulated. The government is either pushing industry to realize some public values in its activities (say, by investing in sustainable growth), or industry is pushing its regulators to promote its own interests.[71] Piketty may worry that, if he too easily accepts this core tenet of politico-economic interdependence, he’ll be dismissed as a statist socialist. But until political economists do so, their work cannot do justice to the voices of those prematurely dead as a result of the relentless pursuit of profit—ranging from the Lonmin miners, to those crushed at Rana Plaza, to the spike of suicides provoked by European austerity and Indian microcredit gone wrong, to the thousands of Americans who will die early because they are stuck in states that refuse to expand Medicaid.[72] Contemporary political economy can only mature if capitalism’s ghosts constrain our theory and practice as pervasively as communism’s specter does.

Renewing Political Economy

Piketty has been compared to Alexis de Tocqueville: a French outsider capable of discerning truths about the United States that its own sages were too close to observe. The function social equality played in Tocqueville’s analysis, is taken up by economic inequality in Piketty’s: a set of self-reinforcing trends fundamentally reshaping the social order.[73] I’ve written tens of thousands of words on this inequality, but the verbal itself may be outmatched in the face of the numbers and force behind these trends.[74] As film director Alex Rivera puts it, in an interview with The New Inquiry:

I don’t think we even have the vocabulary to talk about what we lose as contemporary virtualized capitalism produces these new disembodied labor relations. … The broad, hegemonic clarity is the knowledge that a capitalist enterprise has the right to seek out the cheapest wage and the right to configure itself globally to find it. … The next stage in this process…is for capital to configure itself to enable every single job to be put on the global market through the network.[75]

Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk” has begun that process, supplying “turkers” to perform tasks at a penny each.[76] Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, and various “gig economy” imitators assure that micro-labor is on the rise, leaving micro-wages in its wake.[77] Workers are shifting from paid vacation to stay-cation to “nano-cation” to “paid time off” to hoarding hours to cover the dry spells when work disappears.[78] These developments are all predictable consequences of a globalization premised on maximizing finance rents, top manager compensation, and returns to shareholders.

Inequality is becoming more outrageous than even caricaturists used to dare. The richest woman in the world (Gina Rinehart) has advised fellow Australians to temper their wage demands, given that they are competing against Africans willing to work for two dollars day.[79] Or consider the construct of Dogland, from Korzeniewicz and Moran’s 2009 book, Unveiling Inequality:

The magnitude of global disparities can be illustrated by considering the life of dogs in the United States. According to a recent estimate … in 2007-2008 the average yearly expenses associated with owning a dog were $1425 … For sake of argument, let us pretend that these dogs in the US constitute their own nation, Dogland, with their average maintenance costs representing the average income of this nation of dogs.

By such a standard, their income would place Dogland squarely as a middle-income nation, above countries such as Paraguay and Egypt. In fact, the income of Dogland would place its canine inhabitants above more than 40% of the world population. … And if we were to focus exclusively on health care expenditures, the gap becomes monumental: the average yearly expenditures in Dogland would be higher than health care expenditures in countries that account for over 80% of the world population.[80]

Given disparities like this, wages cannot possibly reflect just desert: who can really argue that a basset hound, however adorable, has “earned” more than a Bangladeshi laborer? Cambridge economist Ha Joon Chang asks us to compare the job and the pay of transport workers in Stockholm and Calcutta. “Skill” has little to do with it. The former, drivers on clean and well-kept roads, may easily be paid fifty times more than the latter, who may well be engaged in backbreaking, and very skilled, labor to negotiate passengers among teeming pedestrians, motorbikes, trucks, and cars.[81]

Once “skill-biased technological change” is taken off the table, the classic economic rationale for such differentials focuses on the incentives necessary to induce labor. In Sweden, for example, the government assures that a person is unlikely to starve, no matter how many hours a week he or she works. By contrast, in India, 42% of the children under five years old are malnourished.[82] So while it takes $15 or $20 an hour just to get the Swedish worker to show up, the typical Indian can be motivated to labor for much less. But of course, at this point the market rationale for the wage differential breaks down entirely, because the background set of social expectations of earnings absent work is epiphenomenal of state-guaranteed patterns of social insurance. The critical questions are: how did the Swedes generate adequate goods and services for their population, and the social commitment to redistribution necessary in order to assure that unemployment is not a death sentence? And how can such social arrangements create basic entitlements to food, housing, health care, and education, around the world?

Piketty’s proposals for regulating capital would be more compelling if they attempted to answer questions like those, rather than focusing on the dry, technocratic aim of tax-driven wealth redistribution. Moreover, even within the realm of tax law and policy, Piketty will need to grapple with several enforcement challenges if a global wealth tax is to succeed. But to its great credit, Capital adopts a methodology capacious enough to welcome the contributions of legal academics and a broad range of social scientists to the study (and remediation) of inequality.[83] It is now up to us to accept the invitation, realizing that if we refuse, accelerating inequality will undermine the relevance—and perhaps even the very existence—of independent legal authority.

Frank Pasquale (@FrankPasquale) is a Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law. His forthcoming book, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms that Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015), develops a social theory of reputation, search, and finance. He blogs regularly at Concurring Opinions. He has received a commission from Triple Canopy to write and present on the political economy of automation. He is a member of the Council for Big Data, Ethics, and Society, and an Affiliate Fellow of Yale Law School’s Information Society Project.

Back to the essay

_____

[1] Dennis Abrams, Piketty’s “Capital”: A Monster Hit for Harvard U Press, Publishing Perspectives, at http://publishingperspectives.com/2014/04/pilkettys-capital-a-monster-hit-for-harvard-u-press/ (Apr. 29, 2014).

[2] Intriguingly, one leading economist who has done serious work on narrative in the field, Dierdre McCloskey, offers a radically different (and far more positive) perspective on the nature of economic growth under capitalism. Evan Thomas, Has Thomas Piketty Met His Match?, http://www.spectator.co.uk/features/9211721/unequal-battle/. But this is to be expected as richer methodologies inform economic analysis. Sometimes the best interpretive social science leads not to consensus, but to ever sharper disagreement about the nature of the phenomena it describes and evaluates. Rather than trying to bury normative differences in jargon or flatten them into commensurable cost-benefit calculations, it surfaces them.

[3] As Thomas Jessen Adams argues, “to understand how inequality has been overcome in the past, we must understand it historically.” Adams, The Theater of Inequality, at http://nonsite.org/feature/the-theater-of-inequality. Adams critiques Piketty for failing to engage historical evidence properly. In this review, I celebrate the book’s bricolage of methodological approaches as the type of problem-driven research promoted by Ian Shapiro.

[4] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century 17 (Arthur Goldhammer trans., 2014).

[5] Doug Henwood, The Top of the World, Book Forum, Apr. 2014, http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/021_01/12987; Suresh Naidu, Capital Eats the World, Jacobin (May 30, 2014), https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/05/capital-eats-the-world/.

[6] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century 25 (Arthur Goldhammer trans., 2014).

[7] Id.

[8] As Piketty observes, war and revolution can also serve this redistributive function. Piketty, supra n. 3, at 20. Since I (and the vast majority of attorneys) do not consider violence a legitimate tool of social change, I do not include these options in my discussion of Piketty’s book.

[9] Frank Pasquale, Access to Medicine in an Era of Fractal Inequality, 19 Annals of Health Law 269 (2010).

[10] Charles R. Morris, The Two Trillion Dollar Meltdown: Easy Money, High Rollers, and the Great Credit Crash 139-40 (2009); see also Edward N. Wolff, Top Heavy: The Increasing Inequality of Wealth in America and What Can Be Done About It 36 (updated ed. 2002).

[11] Yves Smith, Yes, Virginia, the Rich Continue to Get Richer: The Top 1% Get 121% of Income Gains Since 2009, Naked Capitalism (Feb. 13, 2013), http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/02/yes-virginia-the-rich-continue-to-get-richer-the-1-got-121-of-income-gains-since-2009.html#XxsV2mERu5CyQaGE.99.

[12] Larry M. Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age 8,10 (2010).

[13] Id. at 8.

[14] Id. at 10.

[15] Tom Herman, There’s Rich, and There’s the ‘Fortunate 400′, Wall St. J., Mar. 5, 2008, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120468366051012473.html.

[16] See Thomas Piketty & Emmanuel Saez, The Evolution of Top Incomes: A Historical and International Perspective, 96 Am. Econ. Rev. 200, 204 (2006).

[17] Piketty, supra note 4, at 17. Note that, given variations in the data, Piketty is careful to cabin the “geographical and historical boundaries of this study” (27), and must “focus primarily on the wealthy countries and proceed by extrapolation to poor and emerging countries” (28).

[18] Id. at 46, 571 (“In this book, capital is defined as the sum total of nonhuman assets that can be owned and exchanged on some market. Capital includes all forms of real property (including residential real estate) as well as financial and professional capital (plants, infrastructure, machinery, patents, and so on) used by firms and government agencies.”).

[19] Alice Schroeder, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life (Bantam-Dell, 2008); Adam Levine-Weinberg, Warren Buffett Loves a Good Moat, at http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/06/30/warren-buffett-loves-a-good-moat.aspx.

[20] John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971).

[21] Piketty, supra note 4, at 540.

[22] Atul Gawande, Something Wicked This Way Comes, New Yorker (June 28, 2012), http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/something-wicked-this-way-comes.

[23] Philip Mirowski, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown (2013).

[24] The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) was passed in 2010 as part of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act, Pub. L. No. 111-147, 124 Stat. 71 (2010), codified in sections 1471 to 1474 of the Internal Revenue Code, 26 U.S.C. §§ 1471-1474. The law is effective as of 2014. It requires foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to report financial information about accounts held by United States persons, or pay a withholding tax. Id.

[25] Christopher William Sanchirico, Deconstructing the New Efficiency Rationale, 86 Cornell L. Rev. 1003, 1005 (2001).

[26] Nicholas Shaxson, Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens (2012); Jeanna Smialek, The 1% May be Richer than You Think, Bloomberg, Aug. 7, 2014, at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-08-06/the-1-may-be-richer-than-you-think-research-shows.html (collecting economics research).

[27] Andrew Rice, Stash Pad: The New York real-estate market is now the premier destination for wealthy foreigners with rubles, yuan, and dollars to hide, N.Y. Mag., June 29, 2014, at http://nymag.com/news/features/foreigners-hiding-money-new-york-real-estate-2014-6/#.

[28] Ronen Palan, Richard Murphy, and Christian Chavagneux, Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works 272 (2009) (“[m]ore than simple conduits for tax avoidance and evasion, tax havens actually belong to the broad world of finance, to the business of managing the monetary resources of individuals, organizations, and countries. They have become among the most powerful instruments of globalization, one of the principal causes of global financial instability, and one of the large political issues of our times.”).

[29] 26 U.S.C. § 1471-1474 (2012); Itai Grinberg, Beyond FATCA: An Evolutionary Moment for the International Tax System (Georgetown Law Faculty, Working Paper No. 160, 2012), available at http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1162&context=fwps_papers.

[30] David Rothkopf, Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making (2009).

[31] John Chung, Money as Simulacrum: The Legal Nature and Reality of Money, 5 Hasting Bus. L.J. 109,149 (2009).

[32] James S. Henry, Tax Just. Network, The Price Of Offshore Revisited: New Estimates For “Missing” Global Private Wealth, Income, Inequality, And Lost Taxes 3 (2012), available at http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Price_of_Offshore_Revisited_120722.pdf; Scott Highman et al., Piercing the Secrecy of Offshore Tax Havens, Wash. Post (Apr. 6, 2013), http://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/piercing-the-secrecy-of-offshore-tax-havens/2013/04/06/1551806c-7d50-11e2-a044-676856536b40_story.html.

[33] Dev Kar & Devon Cartwright‐Smith, Center for Int’l Pol’y, Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2002-2006 (2012); Jeffrey Sachs, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (2006); Ben Harack, How Much Would it Cost to End Extreme Poverty in the World?, Vision Earth, (Aug. 26, 2011), http://www.visionofearth.org/economics/ending-poverty/how-much-would-it-cost-to-end-extreme-poverty-in-the-world/.

[34] Henry, supra note 68.

[35] Piketty, supra note 4, at 523.

[36] Jeffrey Winters coined the term “wealth defense industry” in his book, Oligarchy. See Frank Pasquale, Understanding Wealth Defense: Direct Action from the 0.1%, at http://www.concurringopinions.com/archives/2011/11/understanding-wealth-defense-direct-action-from-the-0-1.html.

[37] For a similar argument, focusing on the historical specificity of the US parallel to the trente glorieuses, see Thomas Jessen Adams, The Theater of Inequality, http://nonsite.org/feature/the-theater-of-inequality.

[38] Thomas Pogge, The Health Impact Fund: Boosting Pharmaceutical Innovation Without Obstructing Free Access, 18 Cambridge Q. Healthcare Ethics 78 (2008) (proposing global R&D fund);William Fisher III, Promise to Keep: Technology, Law, and the Future of Entertainment (2007); William W. Fisher & Talha Syed, Global Justice in Healthcare: Developing Drugs for the Developing World, 40 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 581 (2006).

[39] Katharina Pistor, A Legal Theory of Finance, 41 J. Comp. Econ. 315 (2013); Law in Finance, 41 J. Comp. Econ (2013). Several other articles in the same journal issue discuss the implications of LTF for derivatives, foreign currency exchange, and central banking.

[40] University of Chicago Law Professor Eric A. Posner and economist Glen Weyl recognize this in their review of Piketty, arguing that “the fundamental problem facing American capitalism is not the high rate of return on capital relative to economic growth that Piketty highlights, but the radical deviation from the just rewards of the marketplace that have crept into our society and increasingly drives talented students out of innovation and into finance.” Posner & Weyl, Thomas Piketty Is Wrong: America Will Never Look Like a Jane Austen Novel,” The New Republic, July 31, 2014, at http://www.newrepublic.com/article/118925/pikettys-capital-theory-misunderstands-inherited-wealth-today. See also Timothy A. Canova, The Federal Reserve We Need, 21 American Prospect 9 (October 2010), at http://prospect.org/article/federal-reserve-we-need.

[41] Timothy Canova, The Federal Reserve We Need: It’s the Fed We Once Had, at http://prospect.org/article/federal-reserve-we-need; Justin Fox, How Economics PhDs Took Over the Federal Reserve, at http://blogs.hbr.org/2014/02/how-economics-phds-took-over-the-federal-reserve/.

[42] Jack M. Balkin, From Off the Wall to On the Wall: How the Mandate Challenge Went Mainstream, Atlantic (June 4, 2012, 2:55 PM), http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/06/from-off-the-wall-to-on-the-wall-how-the-mandate-challenge-went-mainstream/258040/ (Jack Balkin has described how certain arguments go from being ‘off the wall‘ to respectable in constitutional thought; economists have yet to take up that deflationary nomenclature for the evolution of ideas in their own field’s intellectual history. That helps explain the rising power of economists vis a vis lawyers, since the latter field’s honesty about the vagaries of its development diminishes its authority as a ‘science.’). For more on the political consequences of the philosophy of social science, see Jamie Cohen-Cole, The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature (2014), and Joel Isaac, Working Knowledge: Making the Human Sciences from Parsons to Kuhn (2012).

[43] Chris Giles, Piketty Findings Undercut by Errors, Fin. Times (May 23, 2014, 7:00 PM), http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/e1f343ca-e281-11e3-89fd-00144feabdc0.html#axzz399nSmEKj; Thomas Piketty, Addendum: Response to FT, Thomas Piketty (May 28, 2014), http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/Piketty2014TechnicalAppendixResponsetoFT.pdf; Felix Salmon, The Piketty Pessimist, Reuters (April 25, 2014), http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2014/04/25/the-piketty-pessimist/.

[44] Neil Irwin, Everything You Need to know About Thomas Piketty vs. The Financial Times, N.Y. Times (May 30, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/31/upshot/everything-you-need-to-know-about-thomas-piketty-vs-the-financial-times.html

[45] Javier Blas, The Fragile Middle: Rising Inequality in Africa Weighs on New Consumers, Fin. Times (Apr. 18, 2014), http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/49812cde-c566-11e3-89a9-00144feabdc0.html#axzz399nSmEKj.

[46] Jane Owen, Duke of Grafton Uses R&B to Restore Euston Hall’s Pleasure Grounds, Fin. Times (Apr. 18, 2014, 2:03 PM), http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/b49f6dd8-c3bc-11e3-870b-00144feabdc0.html#slide0.

[47] Larry Elliott, Britain’s Five Richest Families Worth More Than Poorest 20%, Guardian, Mar. 16, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/mar/17/oxfam-report-scale-britain-growing-financial-inequality#101.

[48] Piketty, supra note 4, at 570.

[49] Margaret Kimberley, Freedom Rider: Miners Shot Down, Black Agenda Report (June 4, 2014), http://www.blackagendareport.com/content/freedom-rider-miners-shot-down.

[50] Peter Maass, Crude World: The Violent Twilight of Oil (2009); Nicholas Shaxson, Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil (2008).

[51] Piketty, supra note 4, at 539.

[52] Jad Mouawad, Oil Corruption in Equatorial Guinea, N.Y. Times Green Blog (July 9, 2009, 7:01 AM), http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/09/oil-corruption-in-equatorial-guinea; Tina Aridas & Valentina Pasquali, Countries with the Highest GDP Average Growth, 2003–2013, Global Fin. (Mar. 7, 2013), http://www.gfmag.com/component/content/article/119-economic-data/12368-countries-highest-gdp-growth.html#axzz2W8zLMznX; CIA, The World Factbook 184 (2007).

[53] Interview with President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea, CNN’s Amanpour (CNN broadcast Oct. 5, 2012), transcript available at http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1210/05/ampr.01.html.

[54] Peter Maass, A Touch of Crude, Mother Jones, Jan. 2005,http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2005/01/obiang-equatorial-guinea-oil-riggs.

[55] Geraud Magrin & Geert van Vliet, The Use of Oil Revenues in Africa, in Governance of Oil in Africa: Unfinished Business 114 (Jacques Lesourne ed., 2009).

[56] Interview with President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea, supra note 89 .

[57] S. Minority Staff of Permanent Subcomm. on Investigations, Comm. on Gov’t Affairs, 108th Cong., Rep. on Money Laundering and Foreign Corruption: Enforcement and Effectiveness of the Patriot Act 39-40 (Subcomm. Print 2004).

[58] Henry, supra note 68 , at 6, 19-20.

[59] Frank Pasquale, Closed Circuit Economics, New City Reader, Dec. 3, 2010, at 3, at http://neildonnelly.net/ncr/08_Business/NCR_Business_%5BF%5D_web.pdf.

[60] Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred 102 (Perry Link, trans., 2012).

[61] Jesse Drucker, Occupy Wall Street Stylists Pursue U.K. Tax Dodgers, Bloomberg News (June 11, 2013), http://www.businessweek.com/news/2013-06-11/occupy-wall-street-stylists-pursue-u-dot-k-dot-tax-dodgers.

[62] Daniel J. Mitchell, Tax Havens Should Be Emulated, Not Prosecuted, CATO Inst. (Apr. 13, 2009, 12:36 PM), http://www.cato.org/blog/tax-havens-should-be-emulated-not-prosecuted.

[63] Janet Novack, Pritzker Family Baggage: Tax Saving Offshore Trusts, Forbes (May 2, 2013, 8:20 PM), http://www.forbes.com/sites/janetnovack/2013/05/02/pritzker-family-baggage-tax-saving-offshore-trusts/.

[64] Ronen Palan et al., Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works (2013); see also Carolyn Nordstrom, Global Outlaws: Crime, Money, and Power in the Contemporary World (2007), and Loretta Napoleoni, Rogue Economics (2009).

[65] Palan et al., supra note 100 .

[66] Shaxson, supra note 86 , at 24.

[67] Arianna Huffington, Third World America: How Our Politicians Are Abandoning the Middle Class and Betraying the American Dream (2011); Jeffrey A. Winters, Oligarchy (2011); Susan B. Crawford, Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age (2014).

[68] Benjamin Kunkel, Paupers and Richlings, 36 London Rev. Books 17 (2014) (reviewing Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century).

[69] Jeffrey A. Winters, Oligarchy and Democracy, Am. Interest, Sept. 28, 2011, http://www.the-american-interest.com/articles/2011/9/28/oligarchy-and-democracy/.

[70] Id.

[71] James K. Galbraith, The Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the Free Market and Why Liberals Should, Too (2009).

[72] Alex Duval Smith, South Africa Lonmin Mine Massacre Puts Nationalism Back on Agenda, Guardian (Aug. 29, 2012), http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2012/aug/29/south-africa-lonmin-mine-massacre-nationalisation; Charlie Campbell, Dying for Some New Clothes: Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza Tragedy, Time (Apr. 26, 2013), http://world.time.com/2013/04/26/dying-for-some-new-clothes-the-tragedy-of-rana-plaza/; David Stuckler, The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills xiv (2013); Soutik Biswas, India’s Micro-Finance Suicide Epidemic, BBC (Dec. 16, 2010), http://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-11997571; Michael P. O’Donnell, Further Erosion of Our Moral Compass: Failure to Expand Medicaid to Low-Income People in All States, 28 Am. J. Health Promotion iv (2013); Sam Dickman et al., Opting Out of Medicaid Expansion; The Health and Financial Impacts, Health Affairs Blog (Jan. 30, 2014), http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/01/30/opting-out-of-medicaid-expansion-the-health-and-financial-impacts/.

[73] It would be instructive to compare political theorists’ varying models of Tocqueville’s predictive efforts, with Piketty’s sweeping r > g. See, e.g., Roger Boesche, Why Could Tocqueville Predict So Well?, 11 Political Theory 79 (1983) (“Democracy in America endeavors to demonstrate how language, literature, the relations of masters and servants, the status of women, the family, property, politics, and so forth, must change and align themselves in a new, symbiotic configuration as a result of the historical thrust toward equality”); Jon Elster, Alexis de Tocqueville: the First Social Scientist (2012).

[74] See, e.g., Frank Pasquale, Access to Medicine in an Era of Fractal Inequality, 19 Annals of Health Law 269 (2010); Frank Pasquale, The Cost of Conscience: Quantifying our Charitable Burden in an Era of Globalization, at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=584741 (2004); Frank Pasquale, Diagnosing Finance’s Failures: From Economic Idealism to Lawyerly Realism, 6 India L. J. 2 (2012).

[75] Malcolm Harris interview of Alex Rivera, Border Control, New Inquiry (July 2, 2012), http://thenewinquiry.com/features/border-control/.

[76] Trebor Scholz, Digital Labor (Palgrave, forthcoming, 2015); Frank Pasquale, Banana Republic.com, Jotwell (Jan. 14, 2011), http://cyber.jotwell.com/banana-republic-com/.

[77] The Rise of Micro-Labor, On Point with Tom Ashbrook (NPR Apr. 3, 2012, 10:00 AM), http://onpoint.wbur.org/2012/04/03/micro-labor-websites.

[78] Vacation Time, On Point with Tom Ashbrook (NPR June 22, 2012, 10:00 AM), http://onpoint.wbur.org/2012/06/22/vacation-time.

[79] Peter Ryan, Aussies Must Compete with $2 a Day Workers: Rinehart, ABC News (Sept. 25, 2012, 2:56 PM), http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-09-05/rinehart-says-aussie-workers-overpaid-unproductive/4243866.

[80] Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz & Timothy Patrick Moran, Unveiling Inequality, at xv (2012).

[81] Ha Joon Chang, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism 98 (2012).

[82] Jason Burke, Over 40% of Indian Children Are Malnourished, Report Finds, Guardian (Jan. 10, 2012), http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jan/10/child-malnutrition-india-national-shame.

[83] Paul Farmer observes that “an understanding of poverty must be linked to efforts to end it.” Farmer, In the Company of the Poor, at http://www.pih.org/blog/in-the-company-of-the-poor. The same could be said of extreme inequality.