By Audrey Watters

~

Late last year, I gave a similarly titled talk—“Men Explain Technology to Me”—at the University of Mary Washington. (I should note here that the slides for that talk were based on a couple of blog posts by Mallory Ortberg that I found particularly funny, “Women Listening to Men in Art History” and “Western Art History: 500 Years of Women Ignoring Men.” I wanted to do something similar with my slides today: find historical photos of men explaining computers to women. Mostly I found pictures of men or women working separately, working in isolation. Mostly pictures of men and computers.)

So that University of Mary Washington talk: It was the last talk I delivered in 2014, and I did so with a sigh of relief, but also more than a twinge of frightened nausea—nausea that wasn’t nerves from speaking in public. I’d had more than a year full of public speaking under my belt—exhausting enough as I always try to write new talks for each event, but a year that had become complicated quite frighteningly in part by an ongoing campaign of harassment against women on the Internet, particularly those who worked in video game development.

Known as “GamerGate,” this campaign had reached a crescendo of sorts in the lead-up to my talk at UMW, some of its hate aimed at me because I’d written about the subject, demanding that those in ed-tech pay attention and speak out. So no surprise, all this colored how I shaped that talk about gender and education technology, because, of course, my gender shapes how I experience working in and working with education technology. As I discussed then at the University of Mary Washington, I have been on the receiving end of threats and harassment for stories I’ve written about ed-tech—almost all the women I know who have a significant online profile have in some form or another experienced something similar. According to a Pew Research survey last year, one in 5 Internet users reports being harassed online. But GamerGate felt—feels—particularly unhinged. The death threats to Anita Sarkeesian, Zoe Quinn, Brianna Wu, and others were—are—particularly real.

I don’t really want to rehash all of that here today, particularly my experiences being on the receiving end of the harassment; I really don’t. You can read a copy of that talk from last November on my website. I will say this: GamerGate supporters continue to argue that their efforts are really about “ethics in journalism” not about misogyny, but it’s quite apparent that they have sought to terrorize feminists and chase women game developers out of the industry. Insisting that video games and video game culture retain a certain puerile machismo, GamerGate supporters often chastise those who seek to change the content of videos games, change the culture to reflect the actual demographics of video game players. After all, a recent industry survey found women 18 and older represent a significantly greater portion of the game-playing population (36%) than boys age 18 or younger (17%). Just over half of all games are men (52%); that means just under half are women. Yet those who want video games to reflect these demographics are dismissed by GamerGate as “social justice warriors.” Dismissed. Harassed. Shouted down. Chased out.

And yes, more mildly perhaps, the verb that grew out of Rebecca Solnit’s wonderful essay “Men Explain Things to Me” and the inspiration for the title to this talk, mansplained.

Solnit first wrote that essay back in 2008 to describe her experiences as an author—and as such, an expert on certain subjects—whereby men would presume she was in need of their enlightenment and information—in her words “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.” She related several incidents in which men explained to her topics on which she’d published books. She knew things, but the presumption was that she was uninformed. Since her essay was first published the term “mansplaining” has become quite ubiquitous, used to describe the particular online version of this—of men explaining things to women.

I experience this a lot. And while the threats and harassment in my case are rare but debilitating, the mansplaining is more insidious. It is overpowering in a different way. “Mansplaining” is a micro-aggression, a practice of undermining women’s intelligence, their contributions, their voice, their experiences, their knowledge, their expertise; and frankly once these pile up, these mansplaining micro-aggressions, they undermine women’s feelings of self-worth. Women begin to doubt what they know, doubt what they’ve experienced. And then, in turn, women decide not to say anything, not to speak.

I speak from experience. On Twitter, I have almost 28,000 followers, most of whom follow me, I’d wager, because from time to time I say smart things about education technology. Yet regularly, men—strangers, typically, but not always—jump into my “@-mentions” to explain education technology to me. To explain open source licenses or open data or open education or MOOCs to me. Men explain learning management systems to me. Men explain the history of education technology to me. Men explain privacy and education data to me. Men explain venture capital funding of education startups to me. Men explain the business of education technology to me. Men explain blogging and journalism and writing to me. Men explain online harassment to me.

The problem isn’t just that men explain technology to me. It isn’t just that a handful of men explain technology to the rest of us. It’s that this explanation tends to foreclose questions we might have about the shape of things. We can’t ask because if we show the slightest intellectual vulnerability, our questions—we ourselves—lose a sort of validity.

Yet we are living in a moment, I would contend, when we must ask better questions of technology. We neglect to do so at our own peril.

Last year when I gave my talk on gender and education technology, I was particularly frustrated by the mansplaining to be sure, but I was also frustrated that those of us who work in the field had remained silent about GamerGate, and more broadly about all sorts of issues relating to equity and social justice. Of course, I do know firsthand that it can difficult if not dangerous to speak out, to talk critically and write critically about GamerGate, for example. But refusing to look at some of the most egregious acts easily means often ignoring some of the more subtle ways in which marginalized voices are made to feel uncomfortable, unwelcome online. Because GamerGate is really just one manifestation of deeper issues—structural issues—with society, culture, technology. It’s wrong to focus on just a few individual bad actors or on a terrible Twitter hashtag and ignore the systemic problems. We must consider who else is being chased out and silenced, not simply from the video game industry but from the technology industry and a technological world writ large.

I know I have to come right out and say it, because very few people in education technology will: there is a problem with computers. Culturally. Ideologically. There’s a problem with the internet. Largely designed by men from the developed world, it is built for men of the developed world. Men of science. Men of industry. Military men. Venture capitalists. Despite all the hype and hope about revolution and access and opportunity that these new technologies will provide us, they do not negate hierarchy, history, privilege, power. They reflect those. They channel it. They concentrate it, in new ways and in old.

I want us to consider these bodies, their ideologies and how all of this shapes not only how we experience technology but how it gets designed and developed as well.

There’s that very famous New Yorker cartoon: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” The cartoon was first published in 1993, and it demonstrates this sense that we have long had that the Internet offers privacy and anonymity, that we can experiment with identities online in ways that are severed from our bodies, from our material selves and that, potentially at least, the internet can allow online participation for those denied it offline.

Perhaps, yes.

But sometimes when folks on the internet discover “you’re a dog,” they do everything in their power to put you back in your place, to remind you of your body. To punish you for being there. To hurt you. To threaten you. To destroy you. Online and offline.

Neither the internet nor computer technology writ large are places where we can escape the materiality of our physical worlds—bodies, institutions, systems—as much as that New Yorker cartoon joked that we might. In fact, I want to argue quite the opposite: that computer and Internet technologies actually re-inscribe our material bodies, the power and the ideology of gender and race and sexual identity and national identity. They purport to be ideology-free and identity-less, but they are not. If identity is unmarked it’s because there’s a presumption of maleness, whiteness, and perhaps even a certain California-ness. As my friend Tressie McMillan Cottom writes, in ed-tech we’re all supposed to be “roaming autodidacts”: happy with school, happy with learning, happy and capable and motivated and well-networked, with functioning computers and WiFi that works.

By and large, all of this reflects who is driving the conversation about, if not the development of these technology. Who is seen as building technologies. Who some think should build them; who some think have always built them.

And that right there is already a process of erasure, a different sort of mansplaining one might say.

Last year, when Walter Isaacson was doing the publicity circuit for his latest book, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution (2014), he’d often relate of how his teenage daughter had written an essay about Ada Lovelace, a figure whom Isaacson admitted that he’d never heard of before. Sure, he’d written biographies of Steve Jobs and Albert Einstein and Benjamin Franklin and other important male figures in science and technology, but the name and the contributions of this woman were entirely unknown to him. Ada Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron and the woman whose notes on Charles Babbage’s proto-computer the Analytical Engine are now recognized as making her the world’s first computer programmer. Ada Lovelace, the author of the world’s first computer algorithm. Ada Lovelace, the person at the very beginning of the field of computer science.

“Ada Lovelace defined the digital age,” Isaacson said in an interview with The New York Times. “Yet she, along with all these other women, was ignored or forgotten.” (Actually, the world has been celebrating Ada Lovelace Day since 2009.)

Isaacson’s book describes Lovelace like this: “Ada was never the great mathematician that her canonizers claim…” and “Ada believed she possessed special, even supernatural abilities, what she called ‘an intuitive perception of hidden things.’ Her exalted view of her talents led her to pursue aspirations that were unusual for an aristocratic woman and mother in the early Victorian age.” The implication: she was a bit of an interloper.

A few other women populate Isaacson’s The Innovators: Grace Hopper, who invented the first computer compiler and who developed the programming language COBOL. Isaacson describes her as “spunky,” not an adjective that I imagine would be applied to a male engineer. He also talks about the six women who helped program the ENIAC computer, the first electronic general-purpose computer. Their names, because we need to say these things out loud more often: Jean Jennings, Marilyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Betty Snyder, Frances Bilas, Kay McNulty. (I say that having visited Bletchley Park where civilian women’s involvement has been erased, as they were forbidden, thanks to classified government secrets, from talking about their involvement in the cryptography and computing efforts there).

In the end, it’s hard not to read Isaacson’s book without coming away thinking that, other than a few notable exceptions, the history of computing is the history of men, white men. The book mentions education Seymour Papert in passing, for example, but assigns the development of Logo, a programming language for children, to him alone. No mention of the others involved: Daniel Bobrow, Wally Feurzeig, and Cynthia Solomon.

Even a book that purports to reintroduce the contributions of those forgotten “innovators,” that says it wants to complicate the story of a few male inventors of technology by looking at collaborators and groups, still in the end tells a story that ignores if not undermines women. Men explain the history of computing, if you will. As such it tells a story too that depicts and reflects a culture that doesn’t simply forget but systematically alienates women. Women are a rediscovery project, always having to be reintroduced, found, rescued. There’s been very little reflection upon that fact—in Isaacson’s book or in the tech industry writ large.

This matters not just for the history of technology but for technology today. And it matters for ed-tech as well. (Unless otherwise noted, the following data comes from diversity self-reports issued by the companies in 2014.)

- Currently, fewer than 20% of computer science degrees in the US are awarded to women. (I don’t know if it’s different in the UK.) It’s a number that’s actually fallen over the past few decades from a high in 1983 of 37%. Computer science is the only field in science, engineering, and mathematics in which the number of women receiving bachelor’s degrees has fallen in recent years. And when it comes to the employment not just the education of women in the tech sector, the statistics are not much better. (source: NPR)

- 70% of Google employees are male. 61% are white and 30% Asian. Of Google’s “technical” employees. 83% are male. 60% of those are white and 34% are Asian.

- 70% of Apple employees are male. 55% are white and 15% are Asian. 80% of Apple’s “technical” employees are male.

- 69% of Facebook employees are male. 57% are white and 34% are Asian. 85% of Facebook’s “technical” employees are male.

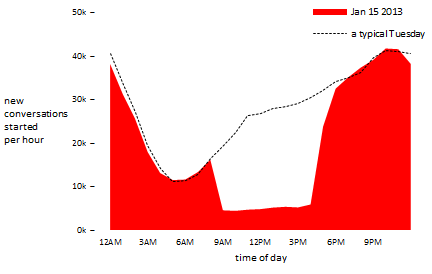

- 70% of Twitter employees are male. 59% are white and 29% are Asian. 90% of Twitter’s “technical” employees are male.

- Only 2.7% of startups that received venture capital funding between 2011 and 2013 had women CEOs, according to one survey.

- And of course, Silicon Valley was recently embroiled in the middle of a sexual discrimination trial involving the storied VC firm Kleiner, Smith, Perkins, and Caulfield filed by former executive Ellen Pao who claimed that men at the firm were paid more and promoted more easily than women. Welcome neither as investors nor entrepreneurs nor engineers, it’s hardly a surprise that, as The Los Angeles Times recently reported, women are leaving the tech industry “in droves.”

This doesn’t just matter because computer science leads to “good jobs” or that tech startups lead to “good money.” It matters because the tech sector has an increasingly powerful reach in how we live and work and communicate and learn. It matters ideologically. If the tech sector drives out women, if it excludes people of color, that matters for jobs, sure. But it matters in terms of the projects undertaken, the problems tackled, the “solutions” designed and developed.

So it’s probably worth asking what the demographics look like for education technology companies. What percentage of those building ed-tech software are men, for example? What percentage are white? What percentage of ed-tech startup engineers are men? Across the field, what percentage of education technologists—instructional designers, campus IT, sysadmins, CTOs, CIOs—are men? What percentage of “education technology leaders” are men? What percentage of education technology consultants? What percentage of those on the education technology speaking circuit? What percentage of those developing not just implementing these tools?

And how do these bodies shape what gets built? How do they shape how the “problem” of education gets “fixed”? How do privileges, ideologies, expectations, values get hard-coded into ed-tech? I’d argue that they do in ways that are both subtle and overt.

That word “privilege,” for example, has an interesting dual meaning. We use it to refer to the advantages that are are afforded to some people and not to others: male privilege, white privilege. But when it comes to tech, we make that advantage explicit. We actually embed that status into the software’s processes. “Privileges” in tech refer to whomever has the ability to use or control certain features of a piece of software. Administrator privileges. Teacher privileges. (Students rarely have privileges in ed-tech. Food for thought.)

Or take how discussion forums operate. Discussion forums, now quite common in ed-tech tools—in learning management systems (VLEs as you call them), in MOOCs, for example—often trace their history back to the earliest Internet bulletin boards. But even before then, education technologies like PLATO, a programmed instruction system built by the University of Illinois in the 1970s, offered chat and messaging functionality. (How education technology’s contributions to tech are erased from tech history is, alas, a different talk.)

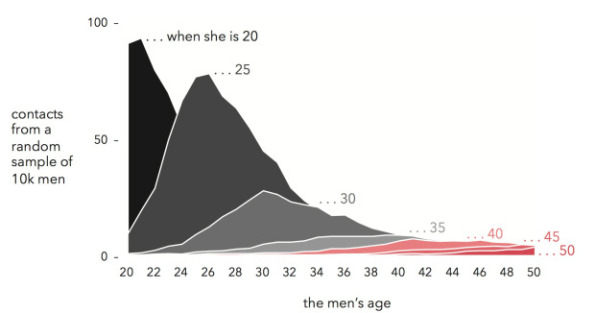

One of the new features that many discussion forums boast: the ability to vote up or vote down certain topics. Ostensibly this means that “the best” ideas surface to the top—the best ideas, the best questions, the best answers. What it means in practice often is something else entirely. In part this is because the voting power on these sites is concentrated in the hands of the few, the most active, the most engaged. And no surprise, “the few” here is overwhelmingly male. Reddit, which calls itself “the front page of the Internet” and is the model for this sort of voting process, is roughly 84% male. I’m not sure that MOOCs, who’ve adopted Reddit’s model of voting on comments, can boast a much better ratio of male to female participation.

What happens when the most important topics—based on up-voting—are decided by a small group? As D. A. Banks has written about this issue,

Sites like Reddit will remain structurally incapable of producing non-hegemonic content because the “crowd” is still subject to structural oppression. You might choose to stay within the safe confines of your familiar subreddit, but the site as a whole will never feel like yours. The site promotes mundanity and repetition over experimentation and diversity by presenting the user with a too-accurate picture of what appeals to the entrenched user base. As long as the “wisdom of the crowds” is treated as colorblind and gender neutral, the white guy is always going to be the loudest.

How much does education technology treat its users similarly? Whose questions surface to the top of discussion forums in the LMS (the VLE), in the MOOC? Who is the loudest? Who is explaining things in MOOC forums?

Ironically—bitterly ironically, I’d say, many pieces of software today increasingly promise “personalization,” but in reality, they present us with a very restricted, restrictive set of choices of who we “can be” and how we can interact, both with our own data and content and with other people. Gender, for example, is often a drop down menu where one can choose either “male” or “female.” Software might ask for a first and last name, something that is complicated if you have multiple family names (as some Spanish-speaking people do) or your family name is your first name (as names in China are ordered). Your name is presented how the software engineers and designers deemed fit: sometimes first name, sometimes title and last name, typically with a profile picture. Changing your username—after marriage or divorce, for example—is often incredibly challenging, if not impossible.

You get to interact with others, similarly, based on the processes that the engineers have determined and designed. On Twitter, you cannot direct message people, for example, that do not follow you. All interactions must be 140 characters or less.

This restriction of the presentation and performance of one’s identity online is what “cyborg anthropologist” Amber Case calls the “templated self.” She defines this as “a self or identity that is produced through various participation architectures, the act of producing a virtual or digital representation of self by filling out a user interface with personal information.”

Case provides some examples of templated selves:

Facebook and Twitter are examples of the templated self. The shape of a space affects how one can move, what one does and how one interacts with someone else. It also defines how influential and what constraints there are to that identity. A more flexible, but still templated space is WordPress. A hand-built site is much less templated, as one is free to fully create their digital self in any way possible. Those in Second Life play with and modify templated selves into increasingly unique online identities. MySpace pages are templates, but the lack of constraints can lead to spaces that are considered irritating to others.

As we—all of us, but particularly teachers and students—move to spend more and more time and effort performing our identities online, being forced to use preordained templates constrains us, rather than—as we have often been told about the Internet—lets us be anyone or say anything online. On the Internet no one knows you’re a dog unless the signup process demanded you give proof of your breed. This seems particularly important to keep in mind when we think about students’ identity development. How are their identities being templated?

While Case’s examples point to mostly “social” technologies, education technologies are also “participation architectures.” Similarly they produce and restrict a digital representation of the learner’s self.

Who is building the template? Who is engineering the template? Who is there to demand the template be cracked open? What will the template look like if we’ve chased women and people of color out of programming?

It’s far too simplistic to say “everyone learn to code” is the best response to the questions I’ve raised here. “Change the ratio.” “Fix the leaky pipeline.” Nonetheless, I’m speaking to a group of educators here. I’m probably supposed to say something about what we can do, right, to make ed-tech more just not just condemn the narratives that lead us down a path that makes ed-tech less son. What we can do to resist all this hard-coding? What we can do to subvert that hard-coding? What we can do to make technologies that our students—all our students, all of us—can wield? What we can do to make sure that when we say “your assignment involves the Internet” that we haven’t triggered half the class with fears of abuse, harassment, exposure, rape, death? What can we do to make sure that when we ask our students to discuss things online, that the very infrastructure of the technology that we use privileges certain voices in certain ways?

The answer can’t simply be to tell women to not use their real name online, although as someone who started her career blogging under a pseudonym, I do sometimes miss those days. But if part of the argument for participating in the open Web is that students and educators are building a digital portfolio, are building a professional network, are contributing to scholarship, then we have to really think about whether or not promoting pseudonyms is a sufficient or an equitable solution.

The answer can’t be simply be “don’t blog on the open Web.” Or “keep everything inside the ‘safety’ of the walled garden, the learning management system.” If nothing else, this presumes that what happens inside siloed, online spaces is necessarily “safe.” I know I’ve seen plenty of horrible behavior on closed forums, for example, from professors and students alike. I’ve seen heavy-handed moderation, where marginalized voices find their input are deleted. I’ve seen zero-moderation, where marginalized voices are mobbed. We recently learned, for example, that Walter Lewin, emeritus professor at MIT, one of the original rockstar professors of YouTube—millions have watched the demonstrations from his physics lectures, has been accused of sexually harassing women in his edX MOOC.

The answer can’t simply be “just don’t read the comments.” I would say that it might be worth rethinking “comments” on student blogs altogether—or rather the expectation that they host them, moderate them, respond to them. See, if we give students the opportunity to “own their own domain,” to have their own websites, their own space on the Web, we really shouldn’t require them to let anyone that can create a user account into that space. It’s perfectly acceptable to say to someone who wants to comment on a blog post, “Respond on your own site. Link to me. But I am under no obligation to host your thoughts in my domain.”

And see, that starts to hint at what I think the answer here to this question about the unpleasantness—by design—of technology. It starts to get at what any sort of “solution” or “alternative” has to look like: it has to be both social and technical. It also needs to recognize there’s a history that might help us understand what’s done now and why. If, as I’ve argued, the current shape of education technologies has been shaped by certain ideologies and certain bodies, we should recognize that we aren’t stuck with those. We don’t have to “do” tech as it’s been done in the last few years or decades. We can design differently. We can design around. We can use differently. We can use around.

One interesting example of this dual approach that combines both social and technical—outside the realm of ed-tech, I recognize—are the tools that Twitter users have built in order to address harassment on the platform. Having grown weary of Twitter’s refusal to address the ways in which it is utilized to harass people (remember, its engineering team is 90% male), a group of feminist developers wrote The Block Bot, an application that lets you block, en masse, a large list of Twitter accounts who are known for being serial harassers. That list of blocked accounts is updated and maintained collaboratively. Similarly, Block Together lets users subscribe to others’ block lists. Good Game Autoblocker, a tool that blocks the “ringleaders” of GamerGate.

That gets, just a bit, at what I think we can do in order to make education technology habitable, sustainable, and healthy. We have to rethink the technology. And not simply as some nostalgia for a “Web we lost,” for example, but as a move forward to a Web we’ve yet to ever see. It isn’t simply, as Isaacson would posit it, rediscovering innovators that have been erased, it’s about rethinking how these erasures happen all throughout technology’s history and continue today—not just in storytelling, but in code.

Educators should want ed-tech that is inclusive and equitable. Perhaps education needs reminding of this: we don’t have to adopt tools that serve business goals or administrative purposes, particularly when they are to the detriment of scholarship and/or student agency—technologies that surveil and control and restrict, for example, under the guise of “safety”—that gets trotted out from time to time—but that have never ever been about students’ needs at all. We don’t have to accept that technology needs to extract value from us. We don’t have to accept that technology puts us at risk. We don’t have to accept that the architecture, the infrastructure of these tools make it easy for harassment to occur without any consequences. We can build different and better technologies. And we can build them with and for communities, communities of scholars and communities of learners. We don’t have to be paternalistic as we do so. We don’t have to “protect students from the Internet,” and rehash all the arguments about stranger danger and predators and pedophiles. But we should recognize that if we want education to be online, if we want education to be immersed in technologies, information, and networks, that we can’t really throw students out there alone. We need to be braver and more compassionate and we need to build that into ed-tech. Like Blockbot or Block Together, this should be a collaborative effort, one that blends our cultural values with technology we build.

Because here’s the thing. The answer to all of this—to harassment online, to the male domination of the technology industry, the Silicon Valley domination of ed-tech—is not silence. And the answer is not to let our concerns be explained away. That is after all, as Rebecca Solnit reminds us, one of the goals of mansplaining: to get us to cower, to hesitate, to doubt ourselves and our stories and our needs, to step back, to shut up. Now more than ever, I think we need to be louder and clearer about what we want education technology to do—for us and with us, not simply to us.

_____

Audrey Watters is a writer who focuses on education technology – the relationship between politics, pedagogy, business, culture, and ed-tech. She has worked in the education field for over 15 years: teaching, researching, organizing, and project-managing. Although she was two chapters into her dissertation (on a topic completely unrelated to ed-tech), she decided to abandon academia, and she now happily fulfills the one job recommended to her by a junior high aptitude test: freelance writer. Her stories have appeared on NPR/KQED’s education technology blog MindShift, in the data section of O’Reilly Radar, on Inside Higher Ed, in The School Library Journal, in The Atlantic, on ReadWriteWeb, and Edutopia. She is the author of the recent book The Monsters of Education Technology (Smashwords, 2014) and working on a book called Teaching Machines. She maintains the widely-read Hack Education blog, on which an earlier version of this review first appeared, and writes frequently for The b2 Review Digital Studies magazine on digital technology and education.