a review of Milton Mueller, Will the Internet Fragment? Sovereignty, Globalization and Cyberspace (Polity, 2017)

by Richard Hill

~

Like other books by Milton Mueller, Will the Internet Fragment? is a must-read for anybody who is seriously interested in the development of Internet governance and its likely effects on other walks of life. This is true because, and not despite, the fact that it is a tract that does not present an unbiased view. On the contrary, it advocates a certain approach, namely a utopian form of governance which Mueller refers to as “popular sovereignty in cyberspace”.

Mueller, Professor of Information Security and Privacy at Georgia Tech, is an internationally prominent scholar specializing in the political economy of information and communication. The author of seven books and scores of journal articles, his work informs not only public policy but also science and technology studies, law, economics, communications, and international studies. His books Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance (MIT Press, 2010) and Ruling the Root: Internet Governance and the Taming of Cyberspace (MIT Press, 2002) are acclaimed scholarly accounts of the global governance regime emerging around the Internet.

Most of Will the Internet Fragment? consists of a rigorous analysis of what has been commonly referred to as “fragmentation,” showing that very different technological and legal phenomena have been conflated in ways that do not favour productive discussions. That so-called “fragmentation” is usually defined as the contrary of the desired situation in which “every device on the Internet should be able to exchange data packets with any other device that is was willing to receive them” (p. 6 of the book, citing Vint Cerf). But. as Mueller correctly points out, not all end-points of the Internet can reach all other end-points at all times, and there may be very good reasons for that (e.g. corporate firewalls, temporary network outages, etc.). Mueller then shows how network effects (the fact that the usefulness of a network increases as it becomes larger) will tend to prevent or counter fragmentation: a subset of the network is less useful than is the whole. He also shows how network effects can prevent the creation of alternative networks: once everybody is using a given network, why switch to an alternative that few are using? As Mueller aptly points out (pp. 63-66), the slowness of the transition to IPv6 is due to this type of network effect.

The key contribution of this book is that it clearly identifies the real question of interest to whose who are concerned about the governance of the Internet and its impact on much of our lives. That question (which might have been a better subtitle) is: “to what extent, if any, should Internet policies be aligned with national borders?” (See in particular pp. 71, 73, 107, 126 and 145). Mueller’s answer is basically “as little as possible, because supra-national governance by the Internet community is preferable”. This answer is presumably motivated by Mueller’s view that “ institutions shift power from states to society” (p. 116), which implies that “society” has little power in modern states. But (at least ideally) states should be the expression of a society (as Mueller acknowledges on pp. 124 and 136), so it would have been helpful if Mueller had elaborated on the ways (and there are many) in which he believes states do not reflect society and in the ways in which so-called multi-stakeholder models would not be worse and would not result in a denial of democracy.

Before commenting on Mueller’s proposal for supra-national governance, it is worth commenting on some areas where a more extensive discussion would have been warranted. We note, however, that the book the book is part of a series that is deliberately intended to be short and accessible to a lay public. So Mueller had a 30,000 word limit and tried to keep things written in a way that non-specialists and non-scholars could access. This no doubt largely explains why he didn’t cover certain topics in more depth.

Be that as it may, the discussion would have been improved by being placed in the long-term context of the steady decrease in national sovereignty that started in 1648, when sovereigns agreed in the Treaty of Westphalia to refrain from interfering in the religious affairs of foreign states, , and that accelerated in the 20th century. And by being placed in the short-term context of the dominance by the USA as a state (which Mueller acknowledges in passing on p. 12), and US companies, of key aspects of the Internet and its governance. Mueller is deeply aware of the issues and has discussed them in his other books, in particular Ruling the Root and Networks and States, so it would have been nice to see the topic treated here, with references to the end of the Cold War and what appears to be re-emergence of some sort of equivalent international tension (albeit not for the same reasons and with different effects at least for what concerns cyberspace). It would also have been preferable to include at least some mention of the literature on the negative economic and social effects of current Internet governance arrangements.

It is telling that, in Will the Internet Fragment?, Mueller starts his account with the 2014 NetMundial event, without mentioning that it took place in the context of the outcomes of the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS, whose genesis, dynamics, and outcomes Mueller well analyzed in Networks and States), and without mentioning that the outcome document of the 2015 UN WSIS+10 Review reaffirmed the WSIS outcomes and merely noted that Brazil had organized NetMundial, which was, in context, an explicit refusal to note (much less to endorse) the NetMundial outcome document.

It is telling that, in Will the Internet Fragment?, Mueller starts his account with the 2014 NetMundial event, without mentioning that it took place in the context of the outcomes of the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS, whose genesis, dynamics, and outcomes Mueller well analyzed in Networks and States), and without mentioning that the outcome document of the 2015 UN WSIS+10 Review reaffirmed the WSIS outcomes and merely noted that Brazil had organized NetMundial, which was, in context, an explicit refusal to note (much less to endorse) the NetMundial outcome document.

The UN’s reaffirmation of the WSIS outcomes is significant because, as Mueller correctly notes, the real question that underpins all current discussions of Internet governance is “what is the role of states?,” and the Tunis Agenda states: “Policy authority for Internet-related public policy issues is the sovereign right of States. They have rights and responsibilities for international Internet-related public policy issues.”

Mueller correctly identifies and discusses the positive externalities created by the Internet (pp. 44-48). It would have been better if he had noted that there are also negative externalities, in particular regarding security (see section 2.8 of my June 2017 submission to ITU’s CWG-Internet), and that the role of states includes internalizing such externalities, as well as preventing anti-competitive behavior.

It is also telling the Mueller never explicitly mentions a principle that is no longer seriously disputed, and that was explicitly enunciated in the formal outcome of the WSIS+10 Review, namely that offline law applies equally online. Mueller does mention some issues related to jurisdiction, but he does not place those in the context of the fundamental principle that cyberspace is subject to the same laws as the rest of the world: as Mueller himself acknowledges (p. 145), allegations of cybercrime are judged by regular courts, not cyber-courts, and if you are convicted you will pay a real fine or be sent to a real prison, not to a cyber-prison. But national jurisdiction is not just about security (p. 74 ff.), it is also about legal certainty for commercial dealings, such as enforcement of contracts. There are an increasing number of activities that depend on the Internet, but that also depend on the existence of known legal regimes that can be enforced in national courts.

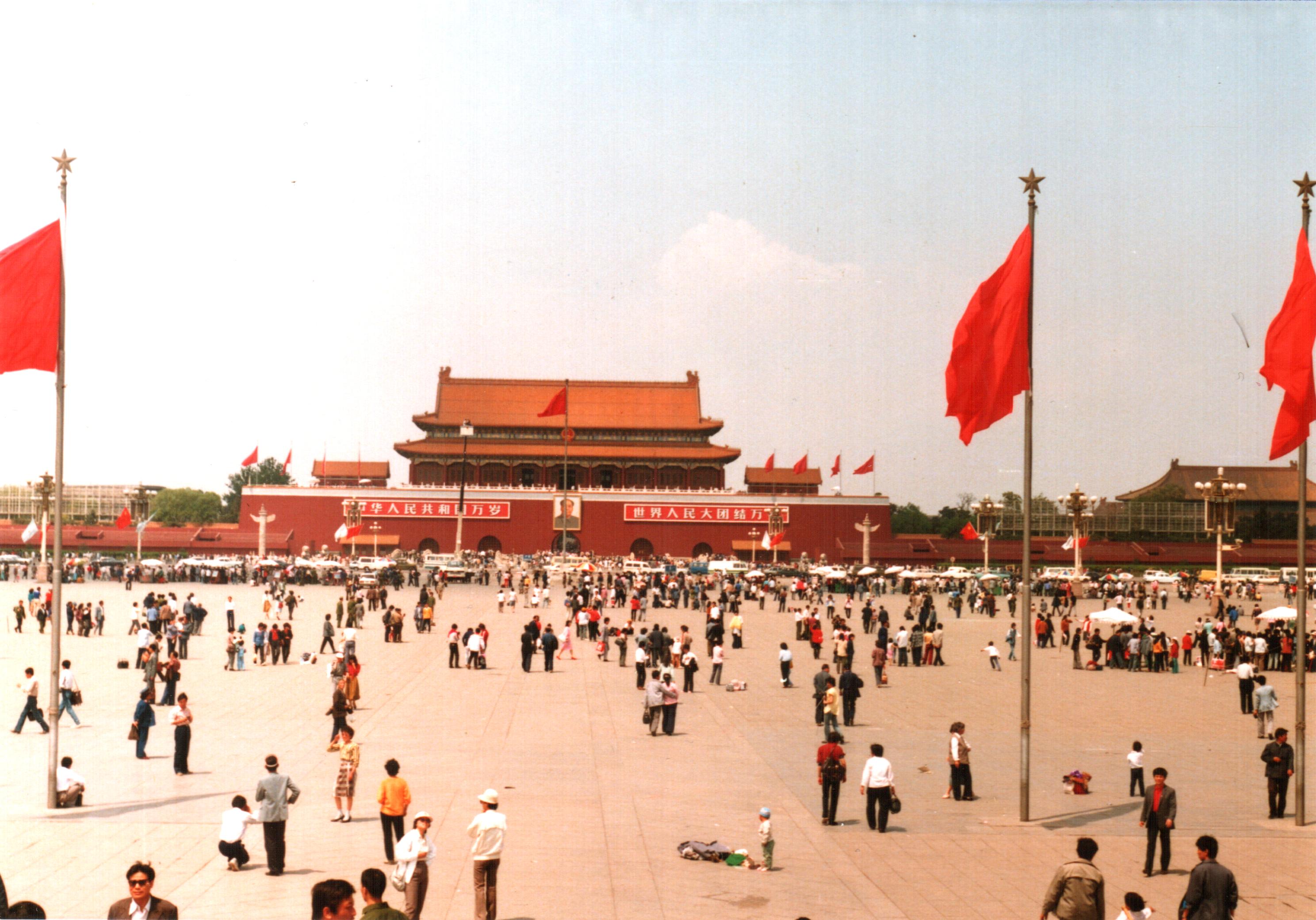

And what about the tension between globalization and other values such as solidarity and cultural diversity? As Mueller correctly notes (p. 10), the Internet is globalization on steroids. Yet cultural values differ around the world (p. 125). How can we get the benefits of both an unfragmented Internet and local cultural diversity (as opposed to the current trend to impose US values on the rest of the world)?

While dealing with these issues in more depth would have complicated the discussion, it also would have made it more valuable, because the call for direct rule of the Internet by and for Internet users must either be reconciled with the principle that offline law applies equally online, or be combined with a reasoned argument for the abandonment of that principle. As Mueller so aptly puts it (p. 11): “Internet governance is hard … also because of the mismatch between its global scope and the political and legal institutions for responding to societal problems.”

Since most laws, and almost all enforcement mechanisms are national, the influence of states on the Internet is inevitable. Recall that the idea of enforceable rules (laws) dates back to at least 1700 BC and has formed an essential part of all civilizations in history. Mueller correctly posits on p. 125 that a justification for territorial sovereignty is to restrict violence (only the state can legitimately exercise it), and wonders why, in that case, the entire world does not have a single government. But he fails to note that, historically, at times much of the world was subject to a single government (think of the Roman Empire, the Mongol Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, the British Empire), and he does not explore the possibility of expanding the existing international order (treaties, UN agencies, etc.) to become a legitimate democratic world governance (which of course it is not, in part because the US does not want it to become one). For example, a concrete step in the direction of using existing governance systems has recently been proposed by Microsoft: a Digital Geneva Convention.

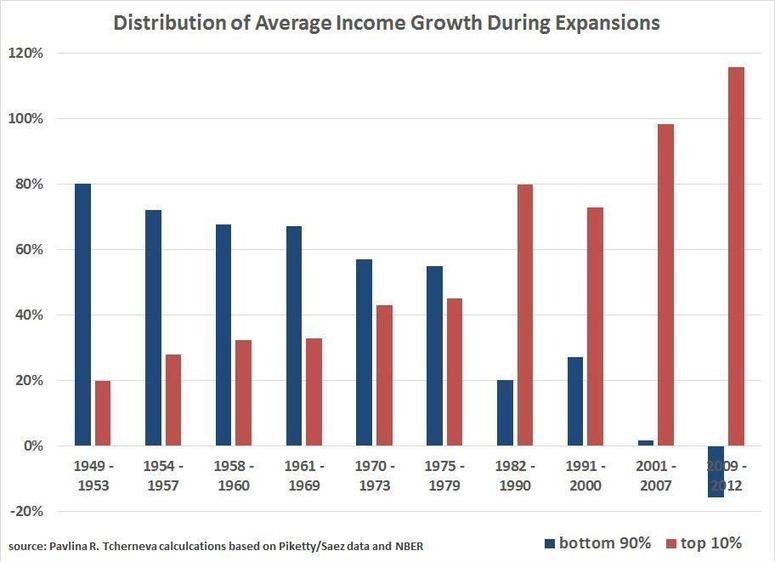

Mueller explains why national borders interfere with certain aspects of certain Internet activities (pp. 104, 106), but national borders interfere with many activities. Yet we accept them because there doesn’t appear to be any “least worst” alternative. Mueller does acknowledge that states have power, and rightly calls for states to limit their exercise of power to their own jurisdiction (p. 148). But he posits that such power “carries much less weight than one would think” (p. 150), without justifying that far-reaching statement. Indeed, Mueller admits that “it is difficult to conceive of an alternative” (p. 73), but does not delve into the details sufficiently to show convincingly how the solution that he sketches would not result in greater power by dominant private companies (and even corpotocracy or corporatism), increasing income inequality, and a denial of democracy. For example, without the power of state in the form of consumer protection measures, how can one ensure that private intermediaries would “moderate content based on user preferences and reports” (p. 147) as opposed to moderating content so as to maximize their profits? Mueller assumes that there would be a sufficient level of competition, resulting in self-correcting forces and accountability (p. 129); but current trends are just the opposite: we see increasing concentration and domination in many aspects of the Internet (see section 2.11 of my June 2017 submission to ITU’s CWG-Internet) and some competition law authorities have found that some abuse of dominance has taken place.

It seems to me that Mueller too easily concludes that “a state-centric approach to global governance cannot easily co-exist with a multistakeholder regime” (p. 117), without first exploring the nuances of multi-stakeholder regimes and the ways that they could interface with existing institutions, which include intergovernmental bodies as well as states. As I have stated elsewhere: “The current arrangement for global governance is arguably similar to that of feudal Europe, whereby multiple arrangements of decision-making, including the Church, cities ruled by merchant-citizens, kingdoms, empires and guilds co-existed with little agreement as to which actor was actually in charge over a given territory or subject matter. It was in this tangled system that the nation-state system gained legitimacy precisely because it offered a clear hierarchy of authority for addressing issues of the commons and provision of public goods.”

Which brings us to another key point that Mueller does not consider in any depth: if the Internet is a global public good, then its governance must take into account the views and needs of all the world’s citizens, not just those that are privileged enough to have access at present. But Mueller’s solution would restrict policy-making to those who are willing and able to participate in various so-called multi-stakeholder forums (apparently Mueller does not envisage a vast increase in participation and representation in these; p. 120). Apart from the fact that that group is not a community in any real sense (a point acknowledged on p. 139), it comprises, at present, only about half of humanity, and even much of that half would not be able to participate because discussions take place primarily in English, and require significant technical knowledge and significant time commitments.

Mueller’s path for the future appears to me to be a modern version of the International Ad Hoc Committee (IAHC), but Mueller would probably disagree, since he is of the view that the IAHC was driven by intergovernmental organizations. In any case, the IAHC work failed to be seminal because of the unilateral intervention of the US government, well described in Ruling the Root, which resulted in the creation of ICANN, thus sparking discussions of Internet governance in WSIS and elsewhere. While Mueller is surely correct when he states that new governance methods are needed (p. 127), it seems a bit facile to conclude that “the nation-state is the wrong unit” and that it would be better to rely largely on “global Internet governance institutions rooted in non-state actors” (p. 129), without explaining how such institutions would be democratic and representative of all of the word’s citizens.

Mueller correctly notes (p. 150) that, historically, there have major changes in sovereignty: emergence and falls of empires, creation of new nations, changes in national borders, etc. But he fails to note that most of those changes were the result of significant violence and use of force. If, as he hopes, the “Internet community” is to assert sovereignty and displace the existing sovereignty of states, how will it do so? Through real violence? Through cyber-violence? Through civil disobedience (e.g. migrating to bitcoin, or implementing strong encryption no matter what governments think)? By resisting efforts to move discussions into the World Trade Organization? Or by persuading states to relinquish power willingly? It would have been good if Mueller had addressed, at least summarily, such questions.

Before concluding, I note a number of more-or-less minor errors that might lead readers to imprecise understandings of important events and issues. For example, p. 37 states that “the US and the Internet technical community created a global institution, ICANN”: in reality, the leaders of the Internet technical community obeyed the unilateral diktat of the US government (at first somewhat reluctantly and later willingly) and created a California non-profit company, ICANN. And ICANN is not insulated from jurisdictional differences; it is fully subject to US laws and US courts. The discussion on pp. 37-41 fails to take into account the fact that a significant portion of the DNS, the ccTLDs, is already aligned with national borders, and that there are non-national telephone numbers; the real differences between the DNS and telephone numbers are that most URLs are non-national, whereas few telephone numbers are non-national; that national telephone numbers are given only to residents of the corresponding country; and that there is an international real-time mechanism for resolving URLs that everybody uses, whereas each telephone operator has to set up its own resolving mechanism for telephone numbers. Page 47 states that OSI was “developed by Europe-centered international organizations”, whereas actually it was developed by private companies from both the USA (including AT&T, Digital Equipment Corporation, Hewlett-Packard, etc.) and Europe working within global standards organizations (IEC, ISO, and ITU), who all happen to have secretariats in Geneva, Switzerland; whereas the Internet was initially developed and funded by an arm of the US Department of Defence and the foundation of the WWW was initially developed in a European intergovernmental organization. Page 100 states that “The ITU has been trying to displace or replace ICANN since its inception in 1998”; whereas a correct statement would be “While some states have called for the ITU to displace or replace ICANN since its inception in 1998, such proposals have never gained significant support and appear to have faded away recently.” Not everybody thinks that the IANA transition was a success (p. 117), nor that it is an appropriate model for the future (pp. 132-135; 136-137), and it is worth noting that ICANN successfully withstood many challenges (p. 100) while it had a formal link to the US government; it remains to be seen how ICANN will fare now that it is independent of the US government. ICANN and the RIR’s do not have a “‘transnational’ jurisdiction created through private contracts” (p. 117); they are private entities subject to national law and the private contracts in question are also subject to national law (and enforced by national authorities, even if disputes are resolved by international arbitration). I doubt that it is a “small step from community to nation” (p. 142), and it is not obvious why anti-capitalist movements (which tend to be internationalist) would “end up empowering territorial states and reinforcing alignment” (p. 147), when it is capitalist movements that rely on the power of territorial states to enforce national laws, for example regarding intellectual property rights.

Despite these minor quibbles, this book, and its references (albeit not as extensive as one would have hoped), will be a valuable starting point for future discussions of internet alignment and/or “fragmentation.” Surely there will be much future discussion, and many more analyses and calls for action, regarding what may well be one of the most important issues that humanity now faces: the transition from the industrial era to the information era and the disruptions arising from that transition.

_____

Richard Hill is President of the Association for Proper internet Governance, and was formerly a senior official at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). He has been involved in internet governance issues since the inception of the internet and is now an activist in that area, speaking, publishing, and contributing to discussions in various forums. Among other works he is the author of The New International Telecommunication Regulations and the Internet: A Commentary and Legislative History (Springer, 2014). He writes frequently about internet governance issues for The b2 Review Digital Studies magazine.