By Audrey Watters

~

After decades of explosive growth, the future of for-profit higher education might not be so bright. Or, depending on where you look, it just might be…

In recent years, there have been a number of investigations – in the media, by the government – into the for-profit college sector and questions about these schools’ ability to effectively and affordably educate their students. Sure, advertising for for-profits is still plastered all over the Web, the airwaves, and public transportation, but as a result of journalistic and legal pressures, the lure of these schools may well be a lot less powerful. If nothing else, enrollment and profits at many for-profit institutions are down.

Despite the massive amounts of money spent by the industry to prop it up – not just on ads but on lobbying and legal efforts, the Obama Administration has made cracking down on for-profits a centerpiece of its higher education policy efforts, accusing these schools of luring students with misleading and overblown promises, often leaving them with low-status degrees sneered at by employers and with loans students can’t afford to pay back.

But the Obama Administration has also just launched an initiative that will make federal financial aid available to newcomers in the for-profit education sector: ed-tech experiments like “coding bootcamps” and MOOCs. Why are these particular for-profit experiments deemed acceptable? What do they do differently from the much-maligned for-profit universities?

School as “Skills Training”

In many ways, coding bootcamps do share the justification for their existence with for-profit universities. That is, they were founded in order to help to meet the (purported) demands of the job market: training people with certain technical skills, particularly those skills that meet the short-term needs of employers. Whether they meet students’ long-term goals remains to be seen.

I write “purported” here even though it’s quite common to hear claims that the economy is facing a “STEM crisis” – that too few people have studied science, technology, engineering, or math and employers cannot find enough skilled workers to fill jobs in those fields. But claims about a shortage of technical workers are debatable, and lots of data would indicate otherwise: wages in STEM fields have remained flat, for example, and many who graduate with STEM degrees cannot find work in their field. In other words, the crisis may be “a myth.”

But it’s a powerful myth, and one that isn’t terribly new, dating back at least to the launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957 and subsequent hand-wringing over the Soviets’ technological capabilities and technical education as compared to the US system.

There are actually a number of narratives – some of them competing narratives – at play here in the recent push for coding bootcamps, MOOCs, and other ed-tech initiatives: that everyone should go to college; that college is too expensive – “a bubble” in the Silicon Valley lexicon; that alternate forms of credentialing will be developed (by the technology sector, naturally); that the tech sector is itself a meritocracy, and college degrees do not really matter; that earning a degree in the humanities will leave you unemployed and burdened by student loan debt; that everyone should learn to code. Much like that supposed STEM crisis and skill shortage, these narratives might be powerful, but they too are hardly provable.

Nor is the promotion of a more business-focused education that new either.

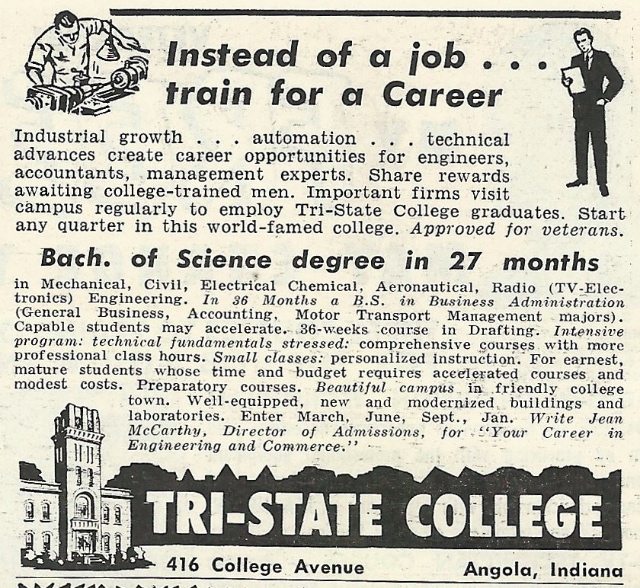

Career Colleges: A History

Foster’s Commercial School of Boston, founded in 1832 by Benjamin Franklin Foster, is often recognized as the first school established in the United States for the specific purpose of teaching “commerce.” Many other commercial schools opened on its heels, most located in the Atlantic region in major trading centers like Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Charleston. As the country expanded westward, so did these schools. Bryant & Stratton College was founded in Cleveland in 1854, for example, and it established a chain of schools, promising to open a branch in every American city with a population of more than 10,000. By 1864, it had opened more than 50, and the chain is still in operation today with 18 campuses in New York, Ohio, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

The curriculum of these commercial colleges was largely based around the demands of local employers alongside an economy that was changing due to the Industrial Revolution. Schools offered courses in bookkeeping, accounting, penmanship, surveying, and stenography. This was in marketed contrast to those universities built on a European model, which tended to teach topics like theology, philosophy, and classical language and literature. If these universities were “elitist,” the commercial colleges were “popular” – there were over 70,000 students enrolled in them in 1897, compared to just 5800 in colleges and universities – something that highlights what’s a familiar refrain still today: that traditional higher ed institutions do not meet everyone’s needs.

The existence of the commercial colleges became intertwined in many success stories of the nineteenth century: Andrew Carnegie attended night school in Pittsburgh to learn bookkeeping, and John D. Rockefeller studied banking and accounting at Folsom’s Commercial College in Cleveland. The type of education offered at these schools was promoted as a path to become a “self-made man.”

That’s the story that still gets told: these sorts of classes open up opportunities for anyone to gain the skills (and perhaps the certification) that will enable upward mobility.

It’s a story echoed in the ones told about (and by) John Sperling as well. Born into a working class family, Sperling worked as a merchant marine, then attended community college during the day and worked as a gas station attendant at night. He later transferred to Reed College, went on to UC Berkeley, and completed his doctorate at Cambridge University. But Sperling felt as though these prestigious colleges catered to privileged students; he wanted a better way for working adults to be able to complete their degrees. In 1976, he founded the University of Phoenix, one of the largest for-profit colleges in the US which at its peak in 2010 enrolled almost 600,000 students.

Other well-known names in the business of for-profit higher education: Walden University (founded in 1970), Capella University (founded in 1993), Laureate Education (founded in 1999), Devry University (founded in 1931), Education Management Corporation (founded in 1962), Strayer University (founded in 1892), Kaplan University (founded in 1937 as The American Institute of Commerce), and Corinthian Colleges (founded in 1995 and defunct in 2015).

It’s important to recognize the connection of these for-profit universities to older career colleges, and it would be a mistake to see these organizations as distinct from the more recent development of MOOCs and coding bootcamps. Kaplan, for example, acquired the code school Dev Bootcamp in 2014. Laureate Education is an investor in the MOOC provider Coursera. The Apollo Education Group, the University of Phoenix’s parent company, is an investor in the coding bootcamp The Iron Yard.

Promises, Promises

Much like the worries about today’s for-profit universities, even the earliest commercial colleges were frequently accused of being “purely business speculations” – “diploma mills” – mishandled by administrators who put the bottom line over the needs of students. There were concerns about the quality of instruction and about the value of the education students were receiving.

That’s part of the apprehension about for-profit universities’ (almost most) recent manifestations too: that these schools are charging a lot of money for a certification that, at the end of the day, means little. But at least the nineteenth century commercial colleges were affordable, UC Berkley history professor Caitlin Rosenthal argues in a 2012 op-ed in Bloomberg,

The most common form of tuition at these early schools was the “life scholarship.” Students paid a lump sum in exchange for unlimited instruction at any of the college’s branches – $40 for men and $30 for women in 1864. This was a considerable fee, but much less than tuition at most universities. And it was within reach of most workers – common laborers earned about $1 per day and clerks’ wages averaged $50 per month.

Many of these “life scholarships” promised that students who enrolled would land a job – and if they didn’t, they could always continue their studies. That’s quite different than the tuition at today’s colleges – for-profit or not-for-profit – which comes with no such guarantee.

Interestingly, several coding bootcamps do make this promise. A 48-week online program at Bloc will run you $24,000, for example. But if you don’t find a job that pays $60,000 after four months, your tuition will be refunded, the startup has pledged.

According to a recent survey of coding bootcamp alumni, 66% of graduates do say they’ve found employment (63% of them full-time) in a job that requires the skills they learned in the program. 89% of respondents say they found a job within 120 days of completing the bootcamp. Yet 21% say they’re unemployed – a number that seems quite high, particularly in light of that supposed shortage of programming talent.

For-Profit Higher Ed: Who’s Being Served?

The gulf between for-profit higher ed’s promise of improved job prospects and the realities of graduates’ employment, along with the price tag on its tuition rates, is one of the reasons that the Obama Administration has advocated for “gainful employment” rules. These would measure and monitor the debt-to-earnings ratio of graduates from career colleges and in turn penalize those schools whose graduates had annual loan payments more than 8% of their wages or 20% of their discretionary earnings. (The gainful employment rules only apply to those schools that are eligible for Title IV federal financial aid.)

The data is still murky about how much debt attendees at coding bootcamps accrue and how “worth it” these programs really might be. According to the aforementioned survey, the average tuition at these programs is $11,852. This figure might be a bit deceiving as the price tag and the length of bootcamps vary greatly. Moreover, many programs, such as App Academy, offer their program for free (well, plus a $5000 deposit) but then require that graduates repay up to 20% of their first year’s salary back to the school. So while the tuition might appear to be low in some cases, the indebtedness might actually be quite high.

According to Course Report’s survey, 49% of graduates say that they paid tuition out of their own pockets, 21% say they received help from family, and just 1.7% say that their employer paid (or helped with) the tuition bill. Almost 25% took out a loan.

That percentage – those going into debt for a coding bootcamp program – has increased quite dramatically over the last few years. (Less than 4% of graduates in the 2013 survey said that they had taken out a loan). In part, that’s due to the rapid expansion of the private loan industry geared towards serving this particular student population. (Incidentally, the two ed-tech companies which have raised the most money in 2015 are both loan providers: SoFi and Earnest. The former has raised $1.2 billion in venture capital this year; the latter $245 million.)

The Obama Administration’s newly proposed “EQUIP” experiment will open up federal financial aid to some coding bootcamps and other ed-tech providers (like MOOC platforms), but it’s important to underscore some of the key differences here between federal loans and private-sector loans: federal student loans don’t have to be repaid until you graduate or leave school; federal student loans offer forbearance and deferment if you’re struggling to make payments; federal student loans have a fixed interest rate, often lower than private loans; federal student loans can be forgiven if you work in public service; federal student loans (with the exception of PLUS loans) do not require a credit check. The latter in particular might help to explain the demographics of those who are currently attending coding bootcamps: if they’re having to pay out-of-pocket or take loans, students are much less likely to be low-income. Indeed, according to Course Report’s survey, the cost of the bootcamps and whether or not they offered a scholarship was one of the least important factors when students chose a program.

Here’s a look at some coding bootcamp graduates’ demographic data (as self-reported):

| Age | |

|---|---|

| Mean Age | 30.95 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 36.3% |

| Male | 63.1% |

| Ethnicity | |

| American Indian | 1.0% |

| Asian American | 14.0% |

| Black | 5.0% |

| Other | 17.2% |

| White | 62.8% |

| Hispanic Origin | |

| Yes | 20.3% |

| No | 79.7% |

| Citizenship | |

| Yes, born in the US | 78.2% |

| Yes, naturalized | 9.7% |

| No | 12.2% |

| Education | |

| High school dropout | 0.2% |

| High school graduate | 2.6% |

| Some college | 14.2% |

| Associate’s degree | 4.1% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 62.1% |

| Master’s degree | 14.2% |

| Professional degree | 1.5% |

| Doctorate degree | 1.1% |

(According to several surveys of MOOC enrollees, these students also tend to be overwhelmingly male from more affluent neighborhoods, and MOOC students also tend to already possess Bachelor’s degrees. The median age of MITx registrants is 27.)

It’s worth considering how the demographics of students in MOOCs and coding bootcamps may (or may not) be similar to those enrolled at other for-profit post-secondary institutions, particularly since all of these programs tend to invoke the rhetoric about “democratizing education” and “expanding access.” Access for whom?

Some two million students were enrolled in for-profit colleges in 2010, up from 400,000 a decade earlier. These students are disproportionately older, African American, and female when compared to the entire higher ed student population. While one in 20 of all students are enrolled in a for-profit college, 1 in 10 African American students, 1 in 14 Latino students, and 1 in 14 first-generation college students are enrolled at a for-profit. Students at for-profits are more likely to be single parents. They’re less likely to enter with a high school diploma. Dependent students in for-profits have about half as much family income as students in not-for-profit schools. (This demographic data is drawn from the NCES and from Harvard University researchers David Deming, Claudia Goldin, and Lawrence Katz in their 2013 study on for-profit colleges.)

Deming, Goldin, and Katz argue that

The snippets of available evidence suggest that the economic returns to students who attend for-profit colleges are lower than those for public and nonprofit colleges. Moreover, default rates on student loans for proprietary schools far exceed those of other higher-education institutions.

According to one 2010 report, just 22% of first- and full-time students pursuing Bachelor’s degrees at for-profit colleges in 2008 graduated, compared to 55% and 65% of students at public and private non-profit universities respectively. Of the more than 5000 career programs that the Department of Education tracks, 72% of those offered by for-profit institutions produce graduates who earn less than high school dropouts.

For their part, today’s MOOCs and coding bootcamps also boast that their students will find great success on the job market. Coursera, for example, recently surveyed its students who’d completed one of its online courses and 72% who responded said they had experienced “career benefits.” But without the mandated reporting that comes with federal financial aid, a lot of what we know about their student population and student outcomes remains pretty speculative.

What kind of students benefit from coding bootcamps and MOOC programs, the new for-profit education? We don’t really know… although based on the history of higher education and employment, we can guess.

EQUIP and the New For-Profit Higher Ed

On October 14, the Obama Administration announced a new initiative, the Educational Quality through Innovative Partnerships (EQUIP) program, which will provide a pathway for unaccredited education programs like coding bootcamps and MOOCs to become eligible for federal financial aid. According to the Department of Education, EQUIP is meant to open up “new models of education and training” to low income students. In a press release, it argues that “Some of these new models may provide more flexible and more affordable credentials and educational options than those offered by traditional higher institutions, and are showing promise in preparing students with the training and education needed for better, in-demand jobs.”

The EQUIP initiative will partner accredited institutions with third-party providers, loosening the “50% rule” that prohibits accredited schools from outsourcing more than 50% of an accredited program. Since bootcamps and MOOC providers “are not within the purview of traditional accrediting agencies,” the Department of Education says, “we have no generally accepted means of gauging their quality.” So those organizations that apply for the experiment will have to provide an outside “quality assurance entity,” which will help assess “student outcomes” like learning and employment.

By making financial aid available for bootcamps and MOOCs, one does have to wonder if the Obama Administration is not simply opening the doors for more of precisely the sort of practices that the for-profit education industry has long been accused of: expanding rapidly, lowering the quality of instruction, focusing on marketing to certain populations (such as veterans), and profiting off of taxpayer dollars.

Who benefits from the availability of aid? And who benefits from its absence? (“Who” here refers to students and to schools.)

Shawna Scott argues in “The Code School-Industrial Complex” that without oversight, coding bootcamps re-inscribe the dominant beliefs and practices of the tech industry. Despite all the talk of “democratization,” this is a new form of gatekeeping.

Before students are even accepted, school admission officers often select for easily marketable students, which often translates to students with the most privileged characteristics. Whether through intentionally targeting those traits because it’s easier to ensure graduates will be hired, or because of unconscious bias, is difficult to discern. Because schools’ graduation and employment rates are their main marketing tool, they have a financial stake in only admitting students who are at low risk of long-term unemployment. In addition, many schools take cues from their professional developer founders and run admissions like they hire for their startups. Students may be subjected to long and intensive questionnaires, phone or in-person interviews, or be required to submit a ‘creative’ application, such as a video. These requirements are often onerous for anyone working at a paid job or as a caretaker for others. Rarely do schools proactively provide information on alternative application processes for people of disparate ability. The stereotypical programmer is once again the assumed default.

And so, despite the recent moves to sanction certain ed-tech experiments, some in the tech sector have been quite vocal in their opposition to more regulations governing coding schools. It’s not just EQUIP either; there was much outcry last year after several states, including California, “cracked down” on bootcamps. Many others have framed the entire accreditation system as a “cabal” that stifles innovation. “Innovation” in this case implies alternate certificate programs – not simply Associate’s or Bachelor’s degrees – in timely, technical topics demanded by local/industry employers.

The Forgotten Tech Ed: Community Colleges

Of course, there is an institution that’s long offered alternate certificate programs in timely, technical topics demanded by local/industry employers, and that’s the community college system.

Vox’s Libby Nelson observed that “The NYT wrote more about Harvard last year than all community colleges combined,” and certainly the conversations in the media (and elsewhere) often ignore that community colleges exist at all, even though these schools educate almost half of all undergraduates in the US.

Like much of public higher education, community colleges have seen their funding shrink in recent decades and have been tasked to do more with less. For community colleges, it’s a lot more with a lot less. Open enrollment, for example, means that these schools educate students who require more remediation. Yet despite many community colleges students being “high need,” community colleges spend far less per pupil than do four-year institutions. Deep budget cuts have also meant that even with their open enrollment policies, community colleges are having to restrict admissions. In 2012, some 470,000 students in California were on waiting lists, unable to get into the courses they need.

This is what we know from history: as the funding for public higher ed decreased – for two- and four-year schools alike, for-profit higher ed expanded, promising precisely what today’s MOOCs and coding bootcamps now insist they’re the first and the only schools to do: to offer innovative programs, training students in the kinds of skills that will lead to good jobs. History tells us otherwise…

_____

Audrey Watters is a writer who focuses on education technology – the relationship between politics, pedagogy, business, culture, and ed-tech. She has worked in the education field for over 15 years: teaching, researching, organizing, and project-managing. Although she was two chapters into her dissertation (on a topic completely unrelated to ed-tech), she decided to abandon academia, and she now happily fulfills the one job recommended to her by a junior high aptitude test: freelance writer. Her stories have appeared on NPR/KQED’s education technology blog MindShift, in the data section of O’Reilly Radar, on Inside Higher Ed, in The School Library Journal, in The Atlantic, on ReadWriteWeb, and Edutopia. She is the author of the recent book The Monsters of Education Technology (Smashwords, 2014) and working on a book called Teaching Machines. She maintains the widely-read Hack Education blog, on which an earlier version of this essay first appeared, and writes frequently for The b2 Review Digital Studies magazine on digital technology and education.