a review of Jen Schradie,The Revolution that Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives (Harvard University Press, 2019)

by Zachary Loeb

~

Despite the oft-repeated, and rather questionable, trope that social media is biased against conservatives; and beyond the attention that has been lavished on tech-savvy left-aligned movements (such as Occupy!) in recent years—this does not necessarily mean that social media is of greater use to the left. It may be quite the opposite. This is a topic that documentary filmmaker, activist and sociologist Jen Schradie explores in depth in her excellent and important book The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatism. Engaging with the political objectives of activists on the left and the right, Schradie’s book considers the political values that are reified in the technical systems themselves and the ways in which those values more closely align with the aims of conservative groups. Furthermore, Schradie emphasizes the socio-economic factors that allow particular groups to successfully harness high-tech tools, thereby demonstrating how digital activism reinforces the power of those who are already enjoying a fair amount of power. Rather than suggesting that high-tech tools have somehow been stolen from the left by the right, The Revolution That Wasn’t argues that these were not the left’s tools in the first place.

The background against which Schradie’s analysis unfolds is the state of North Carolina in the years after 2011. Generally seen as a “red state,” North Carolina had flipped blue for Barack Obama in 2008, leading to the state being increasingly seen as a battleground. Even though the state was starting to take on a purplish color, North Carolina was still home to a deeply entrenched conservativism that was reflected (and still is reflected) in many aspects of the state’s laws, and in the legacy of racist segregation that is still felt in the state. Though the Occupy! movement lingers in the background of Schradie’s account, her focus is on struggles in North Carolina around unionization, the rapid growth of the Tea Party, and the emergence of the “Moral Monday” movement which inspired protests across the state (starting in 2013). While many considerations of digital activism have focused on hip young activists festooned with piercings, hacker skills, and copies of The Coming Insurrection—the central characters of Schradie’s book are members of the labor movement, campus activists, Tea Party members, Preppers, people associated with “Patriot” groups, as well as a smattering of paid organizers working for large organizations. And though Schradie is closely attuned to the impact that financial resources have within activist movements, she pushes back against the “astroturf” accusation that is sometimes aimed at right-wing activists, arguing that the groups she observed on both the right and the left reflected genuine populist movements.

There is a great deal of specificity to Schradie’s study, and many of the things that Schradie observes are particular to the context of North Carolina, but the broader lessons regarding political ideology and activism are widely applicable. In looking at the political landscape in North Carolina, Schradie carefully observes the various groups that were active around the unionization issue, and pays close attention to the ways in which digital tools were used in these groups’ activism. The levels of digital savviness vary across the political groups, and most of the groups demonstrate at least some engagement with digital tools; however, some groups embraced the affordances of digital tools to a much greater extent than others. And where Schradie’s book makes its essential intervention is not simply in showing these differing levels of digital use, but in explaining why. For one of the core observations of Schradie’s account of North Carolina, is that it was not the left-leaning groups, but the right-leaning groups who were able to make the most out of digital tools. It’s a point which, to a large degree, runs counter to general narratives on the left (and possibly also the right) about digital activism.

In considering digital activism in North Carolina, Schradie highlights the “uneven digital terrain that largely abandoned left working-class groups while placing right-wing reformist groups at the forefront of digital activism” (Schradie, 7). In mapping out this terrain, Schradie emphasizes three factors that were pivotal in tilting this ground, namely class, organization, and ideology. Taken independently of one another, each of these three factors provides valuable insight into the challenges posed by digital activism, but taken together they allow for a clear assessment of the ways that digital activism (and digital tools themselves) favor conservatives. It is an analysis that requires some careful wading into definitions (the different ways that right and left groups define things like “freedom” really matters), but these three factors make it clear that “rather than offering a quick technological fix to repair our broken democracy, the advent of digital activism has simply ended up reproducing, and in some cases, intensifying, preexisting power imbalances” (Schradie, 7).

Considering that the core campaign revolves around unionization, it should not particularly be a surprise that class is a major issue in Schradie’s analysis. Digital evangelists have frequently suggested that high-tech tools allow for the swift breaking down of class barriers by providing powerful tools (and informational access) to more and more people—but the North Carolinian case demonstrates the ways in which class endures. Much of this has to do with the persistence of the digital divide, something which can easily be overlooked by onlookers (and academics) who have grown accustomed to digital tools. Schradie points to the presence of “four constraints” that have a pivotal impact on the class aspect of digital activism: “Access, Skills, Empowerment, and Time” (or ASETs for short; Schradie, 61). “Access” points to the most widely understood part of the digital divide, the way in which some people simply do not have a reliable and routine way of getting ahold of and/or using digital tools—it’s hard to build a strong movement online, when many of your members have trouble getting online. This in turn reverberates with “Skills,” as those who have less access to digital tools often lack the know-how that develops from using those tools—not everyone knows how to craft a Facebook post, or how best to make use of hashtags on Twitter. While digital tools have often been praised precisely for the ways in which they empower users, this empowerment is often not felt by those lacking access and skills, leading many individuals from working-class groups to see “digital activism as something ‘other people’ do” (Schradie, 64). And though it may be the easiest factor to overlook, engaging in digital activism requires Time, something which is harder to come by for individuals working multiple jobs (especially of the sort with bosses that do not want to see any workers using phones at work).

When placed against the class backgrounds of the various activist groups considered in the book, the ASETs framework clearly sets up a situation in which conservative activists had the advantage. What Schradie found was “not just a question of the old catching up with the young, but of the poor never being able to catch up with the rich” (Schradie, 79), as the more financially secure conservative activists simply had more ASETs than the working-class activists on the left. And though the right-wing activists skewed older than the left-wing activists, they proved quite capable of learning to use new high-tech tools. Furthermore, an extremely important aspect here is that the working-class activists (given their economic precariousness) had more to lose from engaging in digital activism—the conservative retiree will be much less worried about losing their job, than the garbage truck driver interested in unionizing.

Though the ASETs echo throughout the entirety of Schradie’s account, “Time” plays an essential connective role in the shift from matters of class to matters of organization. Contrary to the way in which the Internet has often been praised for invigorating horizontal movements (such as Occupy!), the activist groups in North Carolina attest to the ways in which old bureaucratic and infrastructural tools are still essential. Or, to put it another way, if the various ASETs are viewed as resources, then having a sufficient quantity of all four is key to maintaining an organization. This meant that groups with hierarchical structures, clear divisions of labor, and more staff (be these committed volunteers or paid workers) were better equipped to exploit the affordances of digital tools.

Importantly, this was not entirely one-sided. Tea Party groups were able to tap into funding and training from larger networks of right-wing organizations, but national unions and civil rights organizations were also able to support left-wing groups. In terms of organization, the overwhelming bias is less pronounced in terms of a right/left dichotomy and more a reflection of a clash between reformist/radical groups. When it came to organization the bias was towards “reformist” groups (right and left) that replicated present power structures and worked within the already existing social systems; the groups that lose out here tend to be the ones that more fully eschew hierarchy (an example of this being student activists). Though digital democracy can still be “participatory, pluralist, and personalized,” Schradie’s analysis demonstrates how “the internet over the long-term favored centralized activism over connective action; hierarchy over horizontalism; bureaucratic positions over networked persons” (Schradie, 134). Thus, the importance of organization, demonstrates not how digital tools allowed for a new “participatory democracy” but rather how standard hierarchical techniques continue to be key for groups wanting to participate in democracy.

Beyond class and organization (insofar as it is truly possible to get past either), the ideology of activists on the left and activists on the right has a profound influence on how these groups use digital tools. For it isn’t the case that the left and the right try to use the Internet for the exact same purpose. Schradie captures this as a difference between pursuing fairness (the left), and freedom (the right)—this largely consisted of left-wing groups seeking a “fairer” allocation of societal power, while those on the right defined “freedom” largely in terms of protecting the allocation of power already enjoyed by these conservative activists. Believing that they had been shut out by the “liberal media,” many conservatives flocked to and celebrated digital tools as a way of getting out “the Truth,” their “digital practices were unequivocally focused on information” (Schradie, 167). As a way of disseminating information, to other people already in possession of ASETs, digital means provided right-wing activists with powerful tools for getting around traditional media gatekeepers. While activists on the left certainly used digital tools for spreading information, their use of the internet tended to be focused more heavily on organizing: on bringing people together in order to advocate for change. Further complicating things for the left is that Schradie found there to be less unity amongst leftist groups in contrast to the relative hegemony found on the right. Comparing the intersection of ideological agendas with digital tools, Schradie is forthright in stating, “the internet was simply more useful to conservatives who could broadcast propaganda and less effective for progressives who wanted to organize people” (Schradie, 223).

Much of the way that digital activism has been discussed by the press, and by academics, has advanced a narrative that frames digital activism as enhancing participatory democracy. In these standard tales (which often ground themselves in accounts of the origins of the internet that place heavy emphasis on the counterculture), the heroes of digital activism are usually young leftists. Yet, as Schradie argues, “to fully explain digital activism in this era, we need to take off our digital-tinted glasses” (Schradie, 259). Removing such glasses reveals the way in which they have too often focused attention on the spectacular efforts of some movements, while overlooking the steady work of others—thus, driving more attention to groups like Occupy!, than to the buildup of right-wing groups. And looking at the state of digital activism through clearer eyes reveals many aspects of digital life that are obvious, yet which are continually forgotten, such as the fact that “the internet is a tool that favors people with more money and power, often leaving those without resources in the dust” (Schradie, 269). The example of North Carolina shows that groups on the left and the right are all making use of the Internet, but it is not just a matter of some groups having more ASETs, it is also the fact that the high-tech tools of digital activism favor certain types of values and aims better than others. And, as Schradie argues throughout her book, those tend to be the causes and aims of conservative activists.

Despite the revolutionary veneer with which the Internet has frequently been painted, “the reality is that throughout history, communications tools that seemed to offer new voices are eventually owned or controlled by those with more resources. They eventually are used to consolidate power, rather than to smash it into pieces and redistribute it” (Schradie, 25). The question with which activists, particularly those on the left, need to wrestle is not just whether or not the Internet is living up to its emancipatory potential—but whether or not it ever really had that potential in the first place.

* * *

In an iconic photograph from 1948, a jubilant Harry S. Truman holds aloft a copy of The Chicago Daily Tribune emblazoned with the headline “Dewey Beats Truman.” Despite the polls having predicted that Dewey would be victorious, when the votes were counted Truman had been sent back to the White House and the Democrats took control of the House and the Senate. An echo of this moment occurred some sixty-eight years later, though there was no comparable photo of Donald Trump smirking while holding up a newspaper carrying the headline “Clinton Beats Trump.” In the aftermath of Trump’s victory pundits ate crow in a daze, pollsters sought to defend their own credibility by emphasizing that their models had never actually said that there was no chance of a Trump victory, and even some in Trump’s circle seemed stunned by his victory.

As shock turned to resignation, the search for explanations and scapegoats began in earnest. Democrats blamed Russian hackers, voter suppression, the media’s obsession with Trump, left-wing voters who didn’t fall in line, and James Comey; while Republicans claimed that the shock was simply proof that the media was out of touch with the voters. Yet, Republicans and Democrats seemed to at least agree on one thing: to understand Trump’s victory, it was necessary to think about social media. Granted, Republicans and Democrats were divided on whether this was a matter of giving credit or assigning blame. On the one hand, Trump had been able to effectively use Twitter to directly engage with his fan base; on the other hand, platforms like Facebook had been flooded with disinformation that spread rapidly through the online ecosystem. It did not take long for representatives, including executives, from the various social media companies to find themselves called before Congress, where these figures were alternately grilled about supposed bias against conservatives on their platforms, and taken to task for how their platforms had been so easily manipulated into helping Trump win election.

If the tech companies were only finding themselves summoned before Congress it would have been bad enough, but they were also facing frustrated employees, as well as disgruntled users, and the word “techlash” was being used to describe the wave of mounting frustration with these companies. Certainly, unease with the power and influence of the tech titans had been growing for years. Cambridge Analytica was hardly the first tech scandal. Yet much of that earlier displeasure was tempered by an overwhelmingly optimistic attitude towards the tech giants, as though the industry’s problematic excesses were indicative of growing pains as opposed to being signs of intrinsic anti-democratic (small d) biases. There were many critics of the tech industry before the arrival of the “techlash,” but they were liable to find themselves denounced as Luddites if they failed to show sufficient fealty to the tech companies. From company CEOs to an adoring tech press to numerous technophilic academics, in the years prior to the 2016 election smart phones and social media were hailed for their liberating and democratizing potential. Videos shot on smart phone cameras and uploaded to YouTube, political gatherings organized on Facebook, activist campaigns turning into mass movements thanks to hashtags—all had been treated as proof positive that high tech tools were breaking apart the old hierarchies and ushering in a new era of high-tech horizontal politics.

Alas, the 2016 election was the rock against which many of these high-tech hopes crashed.

And though there are many strands contributing to the “techlash,” it is hard to make sense of this reaction without seeing it in relation to Trump’s victory. Users of Facebook and Twitter had been frustrated with those platforms before, but at the core of the “techlash” has been a certain sense of betrayal. How could Facebook have done this? Why was Twitter allowing Trump to break its own terms of service on a daily basis? Why was Microsoft partnering with ICE? How come YouTube’s recommendation algorithms always seemed to suggest far-right content?

To state it plainly: it wasn’t supposed to be this way.

But what if it was? And what if it had always been?

In a 1985 interview with MIT’s newspaper The Tech, the computer scientist and social critic, Joseph Weizenbaum had some blunt words about the ways in which computers had impacted society, telling his interviewer: “I think the computer has from the beginning been a fundamentally conservative force. It has made possible the saving of institutions pretty much as they were, which otherwise might have had to be changed” (ben-Aaron, 1985). This was not a new position for Weizenbaum; he had largely articulated the same idea in his 1976 book Computer Power and Human Reason, wherein he had pushed back at those he termed the “artificial intelligentsia” and the other digital evangelists of his day. Articulating his thoughts to the interviewer from The Tech, Weizenbaum raised further concerns about the close links between the military and computer work at MIT, and cast doubt on the real usefulness of computers for society—couching his dire fears in the social critic’s common defense “I hope I’m wrong” (ben-Aaron, 1985). Alas, as the decades passed, Weizenbaum unfortunately felt he had been right. When he turned his critical gaze to the internet in a 2006 interview, he decried the “flood of disinformation,” while noting “it just isn’t true that everyone has access to the so-called Information age” (Weizenbaum and Wendt 2015, 44-45).

Weizenbaum was hardly the only critic to have looked askance at the growing importance that was placed on computers during the 20th century. Indeed, Weizenbaum’s work was heavily influenced by that of his friend and fellow social critic Lewis Mumford who had gone so far as to identify the computer as the prototypical example of “authoritarian” technology (even suggesting that it was the rebirth of the “sun god” in technical form). Yet, societies that are in love with their high-tech gadgets, and which often consider technological progress and societal progress to be synonymous, generally have rather little time for such critics. When times are good, such social critics are safely quarantined to the fringes of academic discourse (and completely ignored within broader society), but when things get rocky they have their woebegone revenge by being proven right.

All of which is to say, that thinkers like Weizenbaum and Mumford would almost certainly agree with The Revolution That Wasn’t. However, they would probably not be surprised by it. After all, The Revolution That Wasn’t is a confirmation that we are today living in the world about which previous generations of critics warned. Indeed, if there is one criticism to be made of Schradie’s work, it is that the book could have benefited by more deeply grounding its analysis in the longstanding critiques of technology that have been made by the likes of Weizenbaum, Mumford, and quite a few other scholars and critics. Jo Freeman and Langdon Winner are both mentioned, but it’s important to emphasize that many social critics warned about the conservative biases of computers long before Trump got a Twitter account, and long before Mark Zuckerberg was born. Our widespread refusal to heed these warnings, and the tendency to mock those issuing these warnings as Luddites, technophobes, and prophets of doom, is arguably a fundamental cause of the present state of affairs which Schradie so aptly describes.

With The Revolution That Wasn’t, Jen Schradie has made a vital intervention in current discussions (inside the academy and amongst activists) regarding the politics of social media. Eschewing a polemical tone, which refuses to sing the praises of social media or to condemn it outright, Schradie provides a measured assessment that addresses the way in which social media is actually being used by activists of varying political stripes—with a careful emphasis on the successes these groups have enjoyed. There is a certain extent to which Schradie’s argument, and some of her conclusions, represent a jarring contrast to much of the literature that has framed social media as being a particular boon to left-wing activists. Yet, Schradie’s book highlights with disarming detail the ways in which a desire (on the part of left-leaning individuals) to believe that the Internet favors people on the left has been a sort of ideological blinder that has prevented them from fully coming to terms with how the Internet has re-entrenched the dominant powers in society.

What Schradie’s book reveals is that “the internet did not wipe out barriers to activism; it just reflected them, and even at times exacerbated existing power differences” (Schradie, 245). Schradie allows the activists on both sides to speak in their own words, taking seriously their claims about what they were doing. And while the book is closely anchored in the context of a particular struggle in North Carolina, the analytical tools that Schradie develops (such as the ASET framework, and the tripartite emphasis on class/organization/ideology) allow Schradie’s conclusions to be mapped onto other social movements and struggles.

While the research that went into The Revolution That Wasn’t clearly predates the election of Donald Trump, and though he is not a main character in the book, the 45th president lurks in the background of the book (or perhaps just in the reader’s mind). Had Trump lost the election, every part of Schradie’s analysis would be just as accurate and biting; however, those seeking to defend social media tools as inherently liberating would probably not be finding themselves on the defensive today (a position that most of them were never expecting themselves to be in). Yet, what makes Schradie’s account so important, is that the book is not simply concerned with whether or not particular movements used digital tools; rather, Schradie is able to step back to consider the degree to which the use of social media tools has been effective in fulfilling the political aims of the various groups. Yes, Occupy! might have made canny use of hashtags (and, if one wants to be generous one can say that it helped inject the discussion of inequality back into American politics), but nearly ten years later the wealth gap is continuing to grow. For all of the hopeful luster that has often surrounded digital tools, Schradie’s book shows the way in which these tools have just placed a fresh coat of paint on the same old status quo—even if this coat of paint is shiny and silvery.

As the technophiles scramble to rescue the belief that the Internet is inherently democratizing, The Revolution That Wasn’t takes its place amongst a growing body of critical works that are willing to challenge the utopian aura that has been built up around the Internet. While it must be emphasized, as the earlier allusion to Weizenbaum shows, that there have been thinkers criticizing computers and the Internet for as long as there have been computers and the Internet—of late there has been an important expansion of such critical works. There is not the space here to offer an exhaustive account of all of the critical scholarship being conducted, but it is worthwhile to mention some exemplary recent works. Safiya Umoja Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression provides an essential examination of the ways in which societal biases, particularly about race and gender, are reinforced by search engines. The recent work on the “New Jim Code” by Ruha Benjamin as seen in such works as Race After Technology, and the Captivating Technology volume she edited, foreground the ways in which technological systems reinforce white supremacy. The work of Virginia Eubanks, both Digital Dead End (whose concerns make it likely the most important precursor to Schradie’s book) and her more recent Automating Inequality, discuss the ways in which high tech systems are used to police and control the impoverished. Examinations of e-waste (such as Jennifer Gabry’s Digital Rubbish) and infrastructure (such as Nicole Starosielski’s The Undersea Network, and Tung-Hui Hu’s A Prehistory of the Cloud) point to the ways in which colonial legacies are still very much alive in today’s high tech systems. While the internationalist sheen that is often ascribed to digital media is carefully deconstructed in works like Ramesh Srnivasan’s Whose Global Village? Works like Meredith Broussard’s Artificial Unintelligence and Shoshana Zuboff’s Age of Surveillance Capitalism raise deep questions about the overall politics of digital technology. And, with its deep analysis of the way that race and class are intertwined with digital access and digital activism, The Revolution That Wasn’t deserves a place amongst such works.

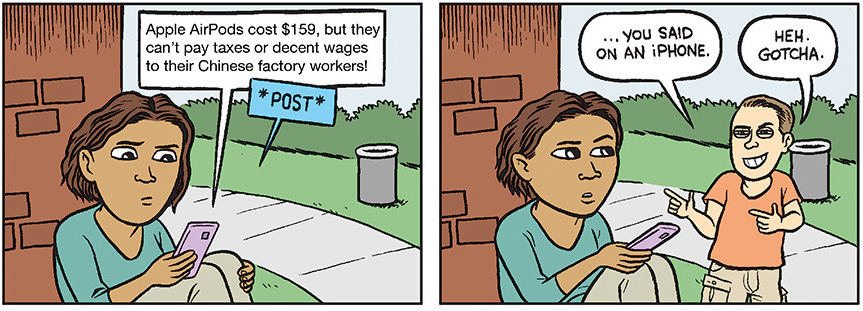

What much of this recent scholarship has emphasized is that technology is never neutral. And while this may be a point which is accepted wisdom amongst scholars in these relevant fields, these works (and scholars) have taken great care to make this point to the broader public. It is not just that tools can be used for good, or for bad—but that tools have particular biases built into them. Pretending those biases aren’t there, doesn’t make them go away. Kranzberg’s Laws asserted that technology is not good, or bad, or neutral—but when one moves away from talking about technology to particular technologies, it is quite important to be able to say that certain technologies may actually be bad. This is a particular problem when one wants to consider things like activism. There has always been something asinine to the tactic of mocking activists pushing for social change while using devices created by massive multinational corporations (as the well-known comic by Matt Bors notes); however, the reason that this mockery is so often repeated is that it has a kernel of troubling truth to it. After all, there is something a little discomforting about using a device running on minerals mined in horrendous conditions, which was assembled in a sweatshop, and which will one day go on to be poisonous e-waste—for organizing a union drive.

Or, to put it slightly differently, when we think about the democratizing potential of technology, to what extent are we privileging those who get to use (and discard) these devices, over those whose labor goes into producing them? That activists may believe that they are using a given device or platform for “good” purposes, does not mean that the device itself is actually good. And this is a tension Schradie gets at when she observes that “instead of a revolutionary participatory tool, the internet just happened to be the dominant communication tool at the time of my research and simply became normalized into the groups’ organizing repertoire” (Schradie, 133). Of course, activists (of varying political stripes) are making use of the communication tools that are available to them and widely used in society. But just because activists use a particular communication tool, doesn’t mean that they should fall in love with it.

This is not in any way to call activists using these tools hypocritical, but it is a further reminder of the ways in which high-tech tools inscribe their users within the very systems they may be seeking to change. And this is certainly a problem that Schradie’s book raises, as she notes that one of the reasons conservative values get a bump from digital tools is that these conservatives are generally already the happy beneficiaries of the systems that created these tools. Scholarship on digital activism has considered the ideologies of various technologically engaged groups before, and there have been many strong works produced on hackers and open source activists, but often the emphasis has been placed on the ideologies of the activists without enough consideration being given to the ways in which the technical tools themselves embody certain political values (an excellent example of a work that truly considers activists picking their tools based on the values of those tools is Christina Dunbar-Hester’s Low Power to the People). Schradie’s focus on ideology is particularly useful here, as it helps to draw attention to the way in which various groups’ ideologies map onto or come into conflict with the ideologies that these technical systems already embody. What makes Schradie’s book so important is not just its account of how activists use technologies, but its recognition that these technologies are also inherently political.

Yet the thorny question that undergirds much of the present discourse around computers and digital tools remains “what do we do if, instead of democratizing society, these tools are doing just the opposite?” And this question just becomes tougher the further down you go: if the problem is just Facebook, you can pose solutions such as regulation and breaking it up; however, if the problem is that digital society rests on a foundation of violent extraction, insatiable lust for energy, and rampant surveillance, solutions are less easily available. People have become so accustomed to thinking that these technologies are fundamentally democratic that they are loathe to believe analyses, such as Mumford’s, that they are instead authoritarian by nature.

While reports of a “techlash” may be overstated, it is clear that at the present moment it is permissible to be a bit more critical of particular technologies and the tech giants. However, there is still a fair amount of hesitance about going so far as to suggest that maybe there’s just something inherently problematic about computers and the Internet. After decades of being told that the Internet is emancipatory, many people remain committed to this belief, even in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary. Trump’s election may have placed some significant cracks in the dominant faith in these digital devices, but suggesting that the problem goes deeper than Facebook or Amazon is still treated as heretical. Nevertheless, it is a matter that is becoming harder and harder to avoid. For it is increasingly clear that it is not a matter of whether or not these devices can be used for this or that political cause, but of the overarching politics of these devices themselves. It is not just that digital activism favors conservatism, but as Weizenbaum observed decades ago, that “the computer has from the beginning been a fundamentally conservative force.”

With The Revolution That Wasn’t, Jen Schradie has written an essential contribution to current conversations around not only the use of technology for political purposes, but also about the politics of technology. As an account of left-wing and right-wing activists, Schradie’s book is a worthwhile consideration of the ways that various activists use these tools. Yet where this, altogether excellent, work really stands out is in the ways in which it highlights the politics that are embedded and reified by high-tech tools. Schradie is certainly not suggesting that activists abandon their devices—in so far as these are the dominant communication tools at present, activists have little choice but to use them—but this book puts forth a nuanced argument about the need for activists to really think critically about whether they’re using digital tools, or whether the digital tools are using them.

_____

Zachary Loeb earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, an MA from the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU, and is currently a PhD candidate in the History and Sociology of Science department at the University of Pennsylvania. Loeb works at the intersection of the history of technology and disaster studies, and his research focusses on the ways that complex technological systems amplify risk, as well as the history of technological doom-saying. He is working on a dissertation on Y2K. Loeb writes at the blog Librarianshipwreck, and is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

_____

Works Cited

- ben-Aaron, Diana. 1985. “Weizenbaum Examines Computers and Society.” The Tech (Apr 9).

- Weizenbaum, Joseph, and Gunna Wendt. 2015. Islands in the Cyberstream: Seeking Havens of Reason in a Programmed Society. Duluth, MN: Litwin Books.

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)