God made the sun so that animals could learn arithmetic – without the succession of days and nights, one supposes, we should not have thought of numbers. The sight of day and night, months and years, has created knowledge of number, and given us the conception of time, and hence came philosophy. This is the greatest boon we owe to sight.

– Plato, Timaeus

The term “computational capital” understands the rise of capitalism as the first digital culture with universalizing aspirations and capabilities, and recognizes contemporary culture, bound as it is to electronic digital computing, as something like Digital Culture 2.0. Rather than seeing this shift from Digital Culture 1.0 to Digital Culture 2.0 strictly as a break, we might consider it as one result of an overall intensification in the practices of quantification. Capitalism, says Nick Dyer-Witheford (2012), was already a digital computer and shifts in the quantity of quantities lead to shifts in qualities. If capitalism was a digital computer from the get-go, then “the invisible hand”—as the non-subjective, social summation of the individualized practices of the pursuit of private (quantitative) gain thought to result in (often unknown and unintended) public good within capitalism—is an early, if incomplete, expression of the computational unconscious. With the broadening and deepening of the imperative toward quantification and rational calculus posited then presupposed during the early modern period by the expansionist program of Capital, the process of the assignation of a number to all qualitative variables—that is, the thinking in numbers (discernible in the commodity-form itself, whereby every use-value was also an encoded as an exchange-value)—entered into our machines and our minds. This penetration of the digital, rendering early on the brutal and precise calculus of the dimensions of cargo-holds in slave ships and the sparse economic accounts of ship ledgers of the Middle Passage, double entry bookkeeping, the rationalization of production and wages in the assembly line, and more recently, cameras and modern computing, leaves no stone unturned. Today, as could be well known from everyday observation if not necessarily from media theory, computational calculus arguably underpins nearly all productive activity and, particularly significant for this argument, those activities that together constitute the command-control apparatus of the world system and which stretch from writing to image-making and, therefore, to thought.[1] The contention here is not simply that capitalism is on a continuum with modern computation, but rather that computation, though characteristic of certain forms of thought, is also the unthought of modern thought. The content indifferent calculus of computational capital ordains the material-symbolic and the psycho-social even in the absence of a conscious, subjective awareness of its operations. As the domain of the unthought that organizes thought, the computational unconscious is structured like a language, a computer language that is also and inexorably an economic calculus.

The computational unconscious allows us to propose that much contemporary consciousness (aka “virtuosity” in post-Fordist parlance) is a computational effect—in short, a form of artificial intelligence. A large part of what “we” are has been conscripted, as thought and other allied metabolic processes are functionalized in the service of the iron clad movements of code. While “iron clad” is now a metaphor and “code” is less the factory code and more computer code, understanding that the logic of industrial machinery and the bureaucratic structures of the corporation and the state have been abstracted and absorbed by discrete state machines to the point where in some quarters “code is law” will allow us to pursue the surprising corollary that all the structural inequalities endemic to capitalist production—categories that often appear under variants of the analog signs of race, class, gender, sexuality, nation, etc., are also deposited and thus operationally disappeared into our machines.

Put simply, and, in deference to contemporary attention spans, too soon, our machines are racial formations. They are also technologies of gender and sexuality.[2] Computational capital is thus also racial capitalism, the longue durée digitization of racialization and, not in any way incidentally, of regimes of gender and sexuality. In other words inequality and structural violence inherent in capitalism also inhere in the logistics of computation and consequently in the real-time organization of semiosis, which is to say, our practices and our thought. The servility of consciousness, remunerated or not, aware of its underlying operating system or not, is organized in relation not just to sociality understood as interpersonal interaction, but to digital logics of capitalization and machine-technics. For this reason, the political analysis of postmodern and, indeed, posthuman inequality must examine the materiality of the computational unconscious. That, at least, is the hypothesis, for if it is the function of computers to automate thinking, and if dominant thought is the thought of domination, then what exactly has been automated?

Already in the 1850s the worker appeared to Marx as a “conscious organ” in the “vast automaton” of the industrial machine, and by the time he wrote the first volume of Capital Marx was able to comment on the worker’s new labor of “watching the machine with his eyes and correcting its mistakes with his hands” (Marx 1867: 496, 502). Marx’s prescient observation with respect to the emergent role of visuality in capitalist production, along with his understanding that the operation of industrial machinery posits and presupposes the operation of other industrial machinery, suggests what was already implicit if not fully generalized in the analysis: that Dr. Ure’s notion, cited by Marx, of the machine as a “vast automaton,” was scalable—smaller machines, larger machines, entire factories could be thus conceived, and with the increasing scale and ubiquity of industrial machines, the notion could well describe the industrial complex as a whole. Historically considered, “watching the machine with his eyes and correcting the mistakes with his hands” thus appears as an early description of what information workers such as you and I do on our screens. To extrapolate: distributed computation and its integration with industrial process and the totality of social processes suggest that not only has society as a whole become a vast automaton profiting from the metabolism of its conscious organs, but further that the confrontation or interface with the machine at the local level (“where we are”) is an isolated and phenomenal experience that is not equivalent to the perspective of the automaton or, under capitalism, that of Capital. Given that here, while we might still be speaking about intelligence, we are not necessarily speaking about subjects in the strict sense, we might replace Althusser’s relation of S-s—Big Subject (God, the State, etc) to small subject (“you” who are interpellated with and in ideology)—with AI-ai— Big Artificial Intelligence (the world system as organized by computational capital) and “you” Little Artificial Intelligence (as organized by the same). Here subjugation is not necessarily intersubjective, and does not require recognition. The AI does not speak your language even if it is your operating system. With this in mind we may at once understand that the space-time regimes of subjectivity (point-perspective, linear time, realism, individuality, discourse function, etc.) that once were part of the digital armature of “the human,” have been profitably shattered, and that the fragments have been multiplied and redeployed under the requisites of new management. We might wager that these outmoded templates or protocols may still also meaningfully refer to a register of meaning and conceptualization that can take the measure of historical change, if only for some kind of species remainder whose value is simultaneously immeasurable, unknown and hanging in the balance.

Ironically perhaps, given the progress narratives attached to technical advances and the attendant advances in capital accumulation, Marx’s hypothesis in Capital Chapter 15, “Machinery and Large-Scale Industry,” that “it would be possible to write a whole history of the inventions made since 1830 for the purpose of providing capital with weapons against working class revolt” (1867, 563), casts an interesting light on the history of computing and its creation-imposition of new protocols. Not only have the incredible innovations of workers been abstracted and absorbed by machinery, but so also have their myriad antagonisms toward capitalist domination. Machinic perfection meant the imposition of continuity and the removal of “the hand of man” by fixed capital, in other words, both the absorption of know-how and the foreclosure of forms of disruption via automation (Marx 1867, 502).

Dialectically understood, subjectivity, while a force of subjugation in some respects, also had its own arsenal of anti-capitalist sensibilities. As a way of talking about non-conformity, anti-sociality and the high price of conformity and its discontents, the unconscious still has its uses, despite its unavoidable and perhaps nostalgic invocation of a future that has itself been foreclosed. The conscious organ does not entirely grasp the cybernetic organism of which it is a part; nor does it fully grasp the rationale of its subjugation. If the unconscious was machinic, it is now computational, and if it is computational it is also locked in a struggle with capitalism. If what underlies perceptual and cognitive experience is the automaton, the vast AI, what I will be referring to as The Computer, which is the totalizing integration of global practice through informatic processes, then from the standpoint of production we constitute its unconscious. However, as we are ourselves unaware of our own constitution, the Unconscious of producers is their/our specific relation to what Paolo Virno acerbically calls, in what can only be a lamentation of history’s perverse irony, “the communism of capital” (2004, 110). If the revolution killed its father (Marx) and married its mother (Capitalism), it may be worth considering the revolutionary prospects of an analysis of this unconscious.

Introduction: The Computational Unconscious

Beginning with the insight that the rise of capitalism marks the onset of the first universalizing digital culture, this essay, and the book of which it is chapter one, develops the insights of The Cinematic Mode of Production (Beller 2006) in an effort to render the violent digital subsumption by computational racial capital that the (former) “humans” and their (excluded) ilk are collectively undergoing in a manner generative of sites of counter-power—of, let me just say it without explaining it, derivatives of counter-power, or, Derivative Communism. To this end, the following section offers a reformulation of Marx’s formula for capital, Money-Commodity-Money’ (M-C-M’), that accounts for distributed production in the social factory, and by doing so hopes to direct attention to zones where capitalist valorization might be prevented or refused. Prevented or refused not only to break a system which itself functions by breaking the bonds of solidarity and mutual trust that formerly were among the conditions that made a life worth living, but also to posit the redistribution of our own power towards ends that for me are still best described by the word communist (or perhaps meta-communist but that too is for another time). This thinking, political in intention, speculative in execution and concrete in its engagement, also proposes a revaluation of the aesthetic as an interface that sensualizes information. As such, the aesthetic is both programmed, and programming—a privileged site (and indeed mode) of confrontation in the digital apartheid of the contemporary.

Along these lines, and similar to the analysis pursued in The Cinematic Mode of Production, I endeavor to de-fetishize a platform—computation itself—one that can only be properly understood when grasped as a means of production embedded in the bios. While computation is often thought of as being the thing accomplished by hardware churning through a program (the programmatic quantum movements of a discrete state machine), it is important to recognize that the universal Turing machine was (and remains) media indifferent only in theory and is thus justly conceived of as an abstract machine in the realm of ideas and indeed of the ruling ideas. However, it is an abstract machine that, like all abstractions, evolves out of concrete circumstances and practices; which is to say that the universal Turing Machine is itself an abstraction subject to historical-materialist critique. Furthermore, Turing Machines iterate themselves on the living, on life, reorganizing its practices. One might situate the emergence and function of the universal Turing machine as perhaps among the most important abstract machines in the last century, save perhaps that of capital itself. However, both their ranking and even their separability is here what we seek to put into question.

Without a doubt, the computational process, like the capitalist process, has a corrosive effect on ontological precepts, accomplishing a far-reaching liquidation of tradition that includes metaphysical assumptions regarding the character of essence, being, authenticity and presence. And without a doubt, computation has been built even as it has been discovered. The paradigm of computation marks an inflection point in human history that reaches along temporal and spatial axes: both into the future and back into the past, out to the cosmos and into the sub-atomic. At any known scale, from plank time (10^-44 seconds) to yottaseconds (10^24 seconds), and from 10^-35 to 10^27 meters, computation, conceptualization and sense-making (sensation) have become inseparable. Computation is part of the historicity of the senses. Just ask that baby using an iPad.

The slight displacement of the ontology of computation implicit in saying that it has been built as much as discovered (that computation has a history even if it now puts history itself at risk) allows us to glimpse, if only from what Laura Mulvey calls “the half-light of the imaginary” (1975, 7)—the general antagonism is feminized when the apparatus of capitalization has overcome the symbolic—that computation is not, so far as we can know, the way of the universe per se, but rather the way of the universe as it has become intelligible to us vis-à-vis our machines. The understanding, from a standpoint recognized as science, that computation has fully colonized the knowable cosmos (and is indeed one with knowing) is a humbling insight, significant in that it allows us to propose that seeing the universe as computation, as, in short, simulable, if not itself a simulation (the computational effect of an informatic universe), may be no more than the old anthropocentrism now automated by apparatuses. We see what we can see with the senses we have—autopoesis. The universe as it appears to us is figured by—that is, it is a figuration of—computation. That’s what our computers tell us. We build machines that discern that the universe functions in accord with their self-same logic. The recursivity effects the God trick.

Parametrically translating this account of cosmic emergence into the domain of history, reveals a disturbing allegiance of computational consciousness organized by the computational unconscious, to what Silvia Federici calls the system of global apartheid. Historicizing computational emergence pits its colonial logic directly against what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney identify as “the general antagonism” (2013, 10) (itself the reparative antithesis, or better perhaps the reverse subsumption of the general intellect as subsumed by capital). The procedural universalization of computation is a cosmology that attributes and indeed enforces a sovereignty tantamount to divinity and externalities be damned. Dissident, fugitive planning and black study – a studied refusal of optimization, a refusal of computational colonialism — may offer a way out of the current geo-(post-)political and its computational orthodoxy.

Computational Idolatry and Multiversality

In the new idolatry cathetcted to inexorable computational emergence, the universe is itself currently imagined as a computer. Here’s the seductive sound of the current theology from a conference sponsored by the sovereign state of NYU:

As computers become progressively faster and more powerful, they’ve gained the impressive capacity to simulate increasingly realistic environments. Which raises a question familiar to aficionados of The Matrix—might life and the world as we know it be a simulation on a super advanced computer? “Digital physicists” have developed this idea well beyond the sci-fi possibilities, suggesting a new scientific paradigm in which computation is not just a tool for approximating reality but is also the basis of reality itself. In place of elementary particles, think bits; in place of fundamental laws of physics, think computer algorithms. (Scientific American 2011)

Science fiction, in the form of “the Matrix,” is here used to figure a “reality” organized by simulation, but then this reality is quickly dismissed as something science has moved well beyond. However, it would not be illogical here to propose that “reality” is itself a science fiction—a fiction whose current author is no longer the novel or Hollywood but science. It is in a way no surprise that, consistent with “digital physics,” MIT physicist, Max Tegmark, claims that consciousness is a state of matter: Consciousness as a phenomenon of information storage and retrieval, is a property of matter described by the term “computronium.” Humans represent a rather low level of complexity. In the neo-Hegelian narrative in which the philosopher—scientist reveals the working out of world—or, rather, cosmic—spirit, one might say that it is as science fiction—one of the persistent fictions licensed by science—that “reality itself” exists at all. We should emphasize that the trouble here is not so much with “reality,” the trouble here is with “itself.” To the extent that we recognize that poesis (making) has been extended to our machines and it is through our machines that we think and perceive, we may recognize that reality is itself a product of their operations. The world begins to look very much like the tools we use to perceive it to the point that Reality itself is thus a simulation, as are we—a conclusion that concurs with the notion of a computational universe, but that seems to (conveniently) elide the immediate (colonial) history of its emergence. The emergence of the tools of perception is taken as universal, or, in the language of a quantum astrophysics that posits four levels of multiverses: multiversal. In brief, the total enclosure by computation of observer and observed is either reality itself becoming self-aware, or tautological, waxing ideological, liquidating as it does historical agency by means of the suddenly a priori stochastic processes of cosmic automation.

Well! If total cosmic automation, then no mistakes, so we may as well take our time-bound chances and wager on fugitive negation in the precise form of a rejection of informatic totalitarianism. Let us sound the sedimented dead labor inherent in the world-system, its emergent computational armature and its iconic self-representations. Let us not forget that those machines are made out of embodied participation in capitalist digitization, no matter how disappeared those bodies may now seem. Marx says, “Consciousness is… from the very beginning a social product and remains so for as long as men exist at all” (Tucker 1978, 178). The inescapable sociality and historicity of knowledge, in short, its political ontology, follows from this—at least so long as humans “exist at all.”

The notion of a computational cosmos, though not universally or even widely consented to by scientific consciousness, suggests that we respire in an aporiatic space—in the null set (itself a sign) found precisely at the intersection of a conclusion reached by Gödel in mathematics (Hofstadter 1979)—that there is no sufficiently powerful logical system that is internally closed such that logical statements cannot be formulated that can neither be proved nor disproved—and a different conclusion reached by Maturana and Varela (1992), and also Niklas Luhmann (1989), that a system’s self-knowing, its autopoesis, knows no outside; it can know only in its own terms and thus knows only itself. In Gödel’s view, systems are ineluctably open, there is no closure, complete self-knowledge is impossible and thus there is always an outside or a beyond, while in the latter group’s view, our philosophy, our politics and apparently our fate is wedded to a system that can know no outside since it may only render an outside in its own terms, unless, or perhaps, even if/as that encounter is catastrophic.

Let’s observe the following: 1) there must be an outside or a beyond (Gödel); 2) we cannot know it (Maturana and Varela); 3) and yet…. In short, we don’t know ourselves and all we know is ourselves. One way out of this aporia is to say that we cannot know the outside and remain what we are. Enter history: Multiversal Cosmic Knoweldge, circa 2017, despite its awesome power, turns out to be pretty local. If we embrace the two admittedly humbling insights regarding epistemic limits—on the one hand, that even at the limits of computationally—informed knowledge (our autopoesis) all we can know is ourselves, along with Gödel’s insight that any “ourselves” whatsoever that is identified with what we can know is systemically excluded from being All—then it as axiomatic that nothing (in all valences of that term) fully escapes computation—for us. Nothing is excluded from what we can know except that which is beyond the horizon of our knowledge, which for us is precisely nothing. This is tantamount to saying that rational epistemology is no longer fully separable from the history of computing—at least for any us who are, willingly or not, participant in contemporary abstraction. I am going to skip a rather lengthy digression about fugitive nothing as precisely that bivalent point of inflection that escapes the computational models of consciousness and the cosmos, and just offer its conclusion as the next step in my discussion: We may think we think—algorithmically, computationally, autonomously, or howsoever—but the historically materialized digital infrastructure of the socius thinks in and through us as well. Or, as Marx put it, “The real subject remains outside the mind and independent of it—that is to say, so long as the mind adopts a purely speculative, purely theoretical attitude. Hence the subject, society, must always be envisaged as the premises of conception even when the theoretical method is employed” (Marx: vol. 28, 38-39).[3]

This “subject, society” in Marx’s terms, is present even in its purported absence—it is inextricable from and indeed overdetermines theory and, thus, thought: in other words, language, narrative, textuality, ideology, digitality, cosmic consciousness. This absent structure informs Althusser’s Lacanian-Marxist analysis of Ideology (and of “the ideology of no ideology,” 1977) as the ideological moment par excellance: an analog way of saying “reality” is simulation) as well as his beguiling (because at once necessary and self-negating) possibility of a subjectless scientific discourse. This non-narrative, unsymbolizeable absent structure akin to the Lacanian “Real” also informs Jameson’s concept of the political unconscious as the black-boxed formal processor of said absent structure, indicated in his work by the term “History” with a capital “H” (1981). We will take up Althusser and Jameson in due time (but not in this paper). For now, however, for the purposes of our mediological investigation, it is important to pursue the thought that precisely this functional overdetermination, which already informed Marx’s analysis of the historicity of the senses in the 1844 manuscripts, extends into the development of the senses and the psyche. As Jameson put it in The Political Unconscious thirty-five years ago: “That the structure of the psyche is historical and has a history, is… as difficult for us to grasp as that the senses are not themselves natural organs but rather the result of a long process of differentiation even within human history”(1981, 62).

The evidence for the accuracy of this claim, built from Marx’s notion that “the forming of the five senses requires the history of the world down to the present” has been increasing. There is a host of work on the inseparability of technics and the so-called human (from Mauss to Simondon, Deleuze and Guattari, and Bernard Stiegler) that increasingly makes it possible to understand and even believe that the human, along with consciousness, the psyche, the senses and, consequently, the unconscious are historical formations. My own essay “The Unconscious of the Unconscious” from The Cinematic Mode of Production traces Lacan’s use of “montage,” “the cut,” the gap, objet a, photography and other optical tropes and argues (a bit too insistently perhaps) that the unconscious of the unconscious is cinema, and that a scrambling of linguistic functions by the intensifying instrumental circulation of ambient images (images that I now understand as derivatives of a larger calculus) instantiates the presumably organic but actually equally technical cinematic black box known as the unconscious.[iv] Psychoanalysis is the institutionalization of a managerial technique for emergent linguistic dysfunction (think literary modernism) precipitated by the onslaught of the visible.

More recently, and in a way that suggests that the computational aspects of historical materialist critique are not as distant from the Lacanian Real as one might think, Lydia Liu’s The Freudian Robot (2010) shows convincingly that Lacan modeled the theory of the unconscious from information theory and cybernetic theory. Liu understands that Lacan’s emphasis on the importance of structure and the compulsion to repeat is explicitly addressed to “the exigencies of chance, randomness, and stochastic processes in general” (2010, 176). She combs Lacan’s writings for evidence that they are informed by information theory and provides us with some smoking guns including the following:

By itself, the play of the symbol represents and organizes, independently of the peculiarities of its human support, this something which is called the subject. The human subject doesn’t foment this game, he takes his place in it, and plays the role of the little pluses and minuses in it. He himself is an element in the chain which, as soon as it is unwound, organizes itself in accordance with laws. Hence the subject is always on several levels, caught up in the crisscrossing of networks. (quoted in Liu 2010, 176)

Liu argues that “the crisscrossing of networks” alludes not so much to linguistic networks but to communication networks, and precisely references the information theory that Lacan read, particularly that of George Gilbaud, the author of What is Cybernetics?. She writes that, “For Lacan, ‘the primordial couple of plus and minus’ or the game of even and odd should precede linguistic considerations and is what enables the symbolic order.”

“You can play heads or tails by yourself,” says Lacan, “but from the point of view of speech, you aren’t playing by yourself – there is already the articulation of three signs comprising a win or a loss and this articulation prefigures the very meaning of the result. In other words, if there is no question, there is no game, if there is no structure, there is no question. The question is constituted, organized by the structure” (quoted in Liu 2010, 179). Liu comments that “[t]his notion of symbolic structure, consistent with game theory, [has] important bearings on Lacan’s paradoxically non-linguistic view of language and the symbolic order.”

Let us not distract ourselves here with the question of whether or not game theory and statistical analysis represent discovery or invention. Heisenberg, Schrödinger, and information theory formalized the statistical basis that one way or another became a global (if not also multiversal) episteme. Norbert Wiener, another father, this time of cybernetics, defined statistics as “the science of distribution” (Weiner 1989, 8). We should pause here to reflect that, given that cybernetic research in the West was driven by military and, later, industrial applications, that is, applications deemed essential for the development of capitalism and the capitalist way of life, such a statement calls for a properly dialectical analysis. Distribution is inseparable from production under capitalism, and statistics is the science of this distribution. Indeed, we would want to make such a thesis resonate with the analysis of logistics recently undertaken by Moten and Harney and, following them, link the analysis of instrumental distribution to the Middle Passage, as the signal early modern consequence of the convergence of rationalization and containerization—precisely the “science” of distribution worked out in the French slave ship Adelaide or the British ship Brookes. For the moment, we underscore the historicity of the “science of distribution” and thus its historical emergence as socio-symbolic system of organization and control. Keeping this emergence clearly in mind helps us to understand that mathematical models quite literally inform the articulation of History and the unconscious—not only homologously as paradigms in intellectual history, but materially, as ways of organizing social production in all domains. Whether logistical, optical or informatic, the technics of mathematical concepts, which is to say programs, orchestrate meaning and constitute the unconscious.

Perhaps more elusive even than this historicity of the unconscious grasped in terms of a digitally encoded matrix of materiality and epistemology that constitutes the unthought of subjective emergence, may be that the notion that the “subject, society” extends into our machines. Vilém Flusser, in Towards a Philosophy of Photography, tells us,

Apparatuses were invented to simulate specific thought processes. Only now (following the invention of the computer), and as it were in hindsight, it is becoming clear what kind of thought processes we are dealing with in the case of all apparatuses. That is: thinking expressed in numbers. All apparatuses (not just computers) are calculating machines and in this sense “artificial intelligences,” the camera included, even if their inventors were not able to account for this. In all apparatuses (including the camera) thinking in numbers overrides linear, historical thinking. (Flusser 2000, 31)

This process of thinking in numbers, and indeed the generalized conversion of multiple forms of thought and practice to an increasingly unified systems language of numeric processing, by capital markets, by apparatuses, by digital computers requires further investigation. And now that the edifice of computation—the fixed capital dedicated to computation that either recognizes itself as such or may be recognized as such—has achieved a consolidated sedimentation of human labor at least equivalent to that required to build a large nation (a superpower) from the ground up, we are in a position to ask in what way has capital-logic and the logic of private property, which as Marx points out is not the cause but the effect of alienated wage- (and thus quantified) labor, structured computational paradigms? In what way has that “subject, society” unconsciously structured not just thought, but machine-thought? Thinking, expressed in numbers, materialized first by means of commodities and then in apparatuses capable of automating this thought. Is computation what we’ve been up to all along without knowing it? Flusser suggests as much through his notion that 1) the camera is a black box that is a programme, and, 2) that the photograph or technical image produces a “magical” relation to the world in as much as people understand the photograph as a window rather than as information organized by concepts. This amounts to the technical image as itself a program for the bios and suggests that the world has long been unconsciously organized by computation vis-à-vis the camera. As Flusser has it, cameras have organized society in a feedback loop that works towards the perfection of cameras. If the computational processes inherent in photography are themselves an extension of capital logic’s universal digitization (an argument I made in The Cinematic Mode of Production and extended in The Message is Murder), then that calculus has been doing its work in the visual reorganization of everyday life for almost two centuries.

Put another way, thinking expressed in numbers (the principles of optics and chemistry) materialized in machines automates thought (thinking expressed in numbers) as program. The program of say, the camera, functions as a historically produced version of what Katherine Hayles has recently called “nonconscious cognition” (Hayles 2016). Though locally perhaps no more self-aware than the sediment sorting process of a riverbed (another of Hayles’s computational examples) the camera nonetheless affects purportedly conscious beings from the domain known as the unconscious, as, to give but one shining example, feminist film theory clearly shows: The function of the camera’s program organizes the psycho-dynamics of the spectator in a way that at once structures film form through market feedback, gratifies the (white-identified) male ego and normalizes the violence of heteropatriarchy, and does so at a profit. Now that so much human time has gone into developing cameras, computer hardware and programming, such that hardware and programming are inextricable from the day to day and indeed nano-second to nano-second organization of life on planet earth (and not only in the form of cameras), we can ask, very pointedly, which aspects of computer function, from any to all, can be said to be conditioned not only by sexual difference but more generally still, by structural inequality and the logistics of racialization? Which computational functions perpetuate and enforce these historically worked up, highly ramified social differences ? Structural and now infra-structural inequalities include social injustices—what could be thought of as and in a certain sense are algorithmic racism, sexism and homophobia, and also programmatically unequal access to the many things that sustain life, and legitimize murder (both long and short forms, executed by, for example, carceral societies, settler colonialism, police brutality and drone strikes), and catastrophes both unnatural (toxic mine-tailings, coltan wars) and purportedly natural (hurricanes, droughts, famines, ambient environmental toxicity). The urgency of such questions resulting from the near automation of geo-political emergence along with a vast conscription of agents is only exacerbated as we recognize that we are obliged to rent or otherwise pay tribute (in the form of attention, subscription, student debt) to the rentier capitalists of the infrastructure of the algorithm in order to access portions of the general intellect from its proprietors whenever we want to participate in thinking.

For it must never be assumed that technology (even the abstract machine) is value-neutral, that it merely exists in some uninterested ideal place and is then utilized either for good or for ill by free men (it would be “men” in such a discourse). Rather, the machine, like Ariella Azoulay’s understanding of photography, has a political ontology—it is a social relation, and an ongoing one whose meaning is, as Azoulay says of the photograph, never at an end (2012, 25). Now that representation has been subsumed by machines, has become machinic (overcoded as Deleuze and Guattari would say) everything that appears, appears in and through the machine, as a machine. For the present (and as Plato already recognized by putting it at the center of the Republic), even the Sun is political. Going back to my opening, the cosmos is merely a collection of billions of suns—an infinite politics.

But really, this political ontology of knowledge, machines, consciousness, praxis should be obvious. How could technology, which of course includes the technologies of knowledge, be anything other than social and historical, the product of social relations? How could these be other than the accumulation, objectification and sedminentation of subjectivities that are themselves an historical product? The historicity of knowledge and perception seems inescapable, if not fully intelligible, particularly now, when it is increasingly clear that it is the programmatic automation of thought itself that has been embedded in our apparatuses. The programming and overdetermination of “choice,” of options, by a rationality that was itself embedded in the interested circumstances of life and continuously “learns” vis-à-vis the feedback life provides has become ubiquitous and indeed inexorable (I dismiss “Object Oriented Ontology” and its desperate effort to erase white-boy subjectivity thusly: there are no ontological objects, only instrumental epistemic horizons). To universalize contemporary subjectivity by erasing its conditions of possibility is to naturalize history; it is therefore to depoliticize it and therefore to recapitulate its violence in the present.

The short answer then regarding digital universality is that technology (and thus perception, thought and knowledge) can only be separated from the social and historical—that is, from racial capitalism—by eliminating both the social and historical (society and history) through its own operations. While computers, if taken as a separate constituency along with a few of their biotic avatars, and then pressed for an answer, might once have agreed with Margaret Thatcher’s view that “there is no such thing as society,” one would be hard-pressed to claim that this post-sociological (and post-Birmingham) “discovery” is a neutral result. Thatcher’s observation, that “the problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money,” while admittedly pithy, if condescending, classist and deadly, subordinates social needs to existing property-relations and their financial calculus at the ontological level. She smugly valorizes the status quo by positing capitalism as an untranscendable horizon since the social product is by definition always already “other people’s money.” But neoliberalism has required some revisioning of late (which is a polite way of saying that fascism has needed some updating): the newish but by now firmly-established term “social media” tells us something more about the parasitic relation that the cold calculus this mathematical universe of numbers has to the bios. To preserve global digital apartheid requires social media, the process(ing) of society itself cybernetically-interfaced with the logistics of racial-capitalist computation. This relation, a means of digital expropriation aimed to profitably exploit an equally significant global aspiration towards planetary communicativity and democratization, has become the preeminent engine of capitalist growth. Society, at first seemingly negated by computation and capitalism, is now directly posited as a source of wealth, for what is now explicitly computational capital and actually computational racial capital. The attention economy, immaterial labor, neuropower, semio-capitalism: all of these terms, despite their differences, mean in effect that society, as a deterritorialized factory, is no longer disappeared as an economic object; it disappears only as a full beneficiary of the dominant economy which is now parasitical on its metabolism. The social revolution in planetary communicativity is being farmed and harvested by computational capitalism.

Dialectics of the Human-Machine

For biologists it has become au courant when speaking of humans to speak also of the second genome—one must consider not just the 26 chromosomes of the human genome that replicate what was thought of as the human being as an autonomous life-form, but the genetic information and epigenetic functionality of all the symbiotic bacteria and other organisms without which there are no humans. Pursuant to this thought, we might ascribe ourselves a third genome: information. No good scientist today believes that human beings are free standing forms, even if most (or really almost all) do not make the critique of humanity or even individuality through a framework that understands these categories as historically emergent interfaces of capitalist exchange. However, to avoid naturalizing the laws of capitalism as simply an expression of the higher (Hegalian) laws of energetics and informatics (in which, for example ATP can be thought to function as “capital”), this sense of “our” embeddedness in the ecosystem of the bios must be extended to that of the materiality of our historical societies, and particularly to their systems of mediation and representational practices of knowledge formation—including the operations of textuality, visuality, data visualization and money—which, with convergence today, means precisely, computation.

If we want to understand the emergence of computation (and of the anthropocene), we must attend to the transformations and disappearances of life forms—of forms of life in the largest sense. And we must do so in spite of the fact that the sedimentation of the history of computation would neutralize certain aspects of human aspiration and of humanity—including, ultimately, even the referent of that latter sign—by means of law, culture, walls, drones, derivatives, what have you. The biosynthetic process of computation and human being gives rise to post-humanism only to reveal that there were never any humans here in the first place: We have never been human—we know this now. “Humanity,” as a protracted example of maiconaissance—as a problem of what could be called the humanizing-machine or, better perhaps, the human-machine, is on the wane.

Naming the human-machine, is of course a way of talking about the conquest, about colonialism, slavery, imperialism, and the racializing, sex-gender norm-enforcing regimes of the last 500 years of capitalism that created the ideological legitimation of its unprecedented violence in the so-called humanistic values it spat out. Aimé Césaire said it very clearly when he posed the scathing question in Discourse on Colonialism: “Civilization and Colonization?” (1972). “The human-machine” names precisely the mechanics of a humanism that at once resulted from and were deployed to do the work of humanizing planet Earth for the quantitative accountings of capital while at the same time divesting a large part of the planetary population of any claims to the human. Following David Golumbia, in The Cultural Logic of Computation (2009), we might look to Hobbes, automata and the component parts of the Leviathan for “human” emergence as a formation of capital. For so many, humanism was in effect more than just another name for violence, oppression, rape, enslavement and genocide—it was precisely a means to violence. “Humanity” as symptom of The Invisible Hand, AI’s avatar. Thus it is possible to see the end of humanism as a result of decolonization struggles, a kind of triumph. The colonized have outlasted the humans. But so have the capitalists.

This is another place where recalling the dialectic is particularly useful. Enlightenment Humanism was a platform for the linear time of industrialization and the French revolution with “the human” as an operating system, a meta-ISA emerging in historical movement, one that developed a set of ontological claims which functioned in accord with the early period of capitalist digitality. The period was characterized by the institutionalization of relative equality (Cedric Robinson does not hesitate to point out that the precondition of the French Revolution was colonial slavery), privacy, property. Not only were its achievements and horrors inseparable the imposition of logics of numerical equivalence, they were powered by the labor of the peoples of Earth, by the labor-power of disparate peoples, imported as sugar and spices, stolen as slaves, music and art, owned as objective wealth in the form of lands, armies, edifices and capital, and owned again as subjective wealth in the form of cultural refinement, aesthetic sensibility, bourgeois interiority—in short, colonial labor, enclosed by accountants and the whip, was expatriated as profit, while industrial labor, also expropriated, was itself sustained by these endeavors. The accumulation of the wealth of the world and of self-possession for some was organized and legitimated by humanism, even as those worlded by the growth of this wealth struggled passionately, desultorily, existentially, partially and at times absolutely against its oppressive powers of objectification and quantification. Humanism was colonial software, and the colonized were the outsourced content providers—the first content providers—recruited to support the platform of so-called universal man. This platform humanism is not so much a metaphor; rather it is the tendency that is unveiled by the present platform post-humanism of computational racial capital. The anatomy of man is the key to the anatomy of the ape, as Marx so eloquently put the telos of man. Is the anatomy of computation the key to the anatomy of “man”?

So the end of humanism, which in a narrow (white, Euro-American, technocratic) view seems to arrive as a result of the rise of cyber-technologies, must also be seen as having been long willed and indeed brought about by the decolonizing struggles against humanism’s self-contradictory and, from the point of view of its own self-proclaimed values, specious organization. Making this claim is consistent with Césaire’s insight that people of the third world built the European metropoles. Today’s disappearance of the human might mean for the colonizers who invested so heavily in their humanisms, that Dr. Moreau’s vivisectioned cyber-chickens are coming home to roost. Fatally, it seems, since Global North immigration policy, internment centers, border walls, police forces give the lie to any pretense of humanism. It might be gleaned that the revolution against the humans has also been impacted by our machines. However, the POTUSian defeat of the so-called humans is double-edged to say the least. The dialectic of posthuman abundance on the one hand and the posthuman abundance of dispossession on the other has no truck with humanity. Today’s mainstream futurologists mostly see “the singularity” and apocalypse. Critics of the posthuman with commitments to anti-racist world-making have clearly understood the dominant discourse on the posthuman as not the end of the white liberal human subject but precisely, when in the hands of those not committed to an anti-racist and decolonial project as a means for its perpetuation—a way of extending the unmarked, transcendental, sovereign, subject (of Hobbes, Descartes, C.B. Macpherson)—effectively the white male sovereign who was in possession of a body rather than forced to be a body. Sovereignty itself must change (in order, as Guiseppe Lampedusa taught us, to remain the same), for if one sees production and innovation on the side of labor, then capital’s need to contain labors’ increasing self-organization has driven it into a position where the human has become an impediment to its continued expansion. Human rights, though at times also a means to further expropriation, are today in the way.

Let’s say that it is global labor that is shaking off the yoke of the human from without, as much as it the digital machines that are devouring it from within. The dialectic of computational racial capital devours the human as a way of revolutionizing the productive forces. Weapon-makers, states, and banks, along with Hollywood and student debt, invoke the human only as a skeuomorph—an allusion to an old technology that helps facilitate adoption of the new. Put another way, the human has become a barrier to production, it is no longer a sustainable form. The human, and those (human and otherwise) falling under the paradigm’s dominion, must be stripped, cut, bundled, reconfigured in derivative forms. All hail the dividual. Again, female and racialized bodies and subjects have long endured this now universal fragmentation and forced recomposition and very likely dividuality may also describe a precapitalist, pre-colonial interface with the social. However we are obliged to point out that this, the current dissolution of the human into the infrastructure of the world-system, is double-edged, neither fully positive, nor fully negative—the result of the dialectics of struggles for liberation distributed around the planet. As a sign of the times, posthumanism may be, as has been remarked about capitalism itself, among those simultaneously best and worst things to ever happen in history. On the one hand, the disappearance of presumably ontological protections and legitimating status for some (including the promise of rights never granted to most), on the other, the disappearance of a modality of dehumanization and exclusion that legitimated and normalized white supremacist patriarchy by allowing its values to masquerade as universals. However, it is difficult to maintain optimism of the will when we see that that which is coming, that which is already upon us may also be as bad or worse, in absolute numbers, is already worse, for unprecedented billions of concrete individuals. Frankly, in a world where the cognitive-linguistic functions of the species have themselves been captured by the ambient capitalist computation of social media and indeed of capitalized computational social relations, of what use is a theory of dispossession to the dispossessed?

For those of us who may consider ourselves thinkers, it is our burden—in a real sense, our debt, living and ancestral—to make theory relevant to those who haunt it. Anything less is betrayal. The emergence of the universal value form (as money, the general form of wealth) with its human face (as white-maleness, the general form of humanity) clearly inveighs against the possibility of extrinsic valuation since the very notion of universal valuation is posited from within this economy. What Cedric Robinson shows in his extraordinary Black Marxism (1983) is that capitalism itself is a white mythology. The history of racialization and capitalization are inseparable, and the treatment of capital as a pure abstraction deracinates its origins and functions – both its conditions of possibility as well as its operations—including those of the internal critique of capitalism that has been the basis of much of the Marxist tradition. Both capitalism and its negation as Marxism have proceeded through a disavowal of racialization. The quantitative exchange of equivalents, circulating as exchange values without qualities, are the real abstractions that give rise to philosophy, science, and white liberal humanism wedded to the notion of the objective. Therefore, when it comes to values, there is no degree zero, only perhaps nodal points of bounded equilibrium. To claim neutrality for an early digital machine, say, money, that is, to argue that money as a medium is value-neutral because it embodies what has (in many respects correctly, but in a qualified way) been termed “the universal value form,” would be to miss the entire system of leveraged exploitation that sustains the money-system. In an isolated instance, money as the product of capital might be used for good (building shelters for the homeless) or for ill (purchasing Caterpillar bulldozers) or both (building shelters using Caterpillar machines), but not to see that the capitalist-system sustains itself through militarized and policed expropriation and large-scale, long-term universal degradation is to engage in mere delusional, utopianism and self-interested (might one even say psychotic?) naysaying.

Will the apologists calmly bear witness to the sacrifice of billions of human beings so that the invisible hand may placidly unfurl its/their abstractions in Kubrikian sublimity? 2001’s (Kubrick 1968) cold longshot of the species lifespan as an instance of a cosmic program is not so distant from the endemic violence of postmodern—and, indeed, post-human—fascism he depicted in A Clockwork Orange (Kubrick 1971). Arguably, 2001 rendered the cosmology of early Posthuman Fascism while A Clockwork Orange portrayed its psychology. Both films explored the aesthetics of programming. For the individual and for the species, what we beheld in these two films was the annihilation of our agency (at the level of the individual and of the species) —and it was eerily seductive, Benjamin’s self-destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the highest order taken to cosmic proportions and raised to the level of Art (1969).

So what of the remainders of those who may remain? Here, in the face of the annihilation of remaindered life (to borrow a powerfully dialectical term from Neferti Tadiar, 2016) by various iterations of techné, we are posing the following question: how are computers and digital computing, as universals, themselves an iteration of long-standing historical inequality, violence, and murder, and what are the entry points for an understanding of computation-society in which our currently pre-historic (in Marx’s sense of the term) conditions of computation might be assessed and overcome? This question of technical overdetermination is not a matter of a Kittlerian-style anti-humanism in which “media determine our situation,” nor is it a matter of the post-Kittlerian, seemingly user-friendly repurposing of dialectical materialism which in the beer-drinking tradition of “good-German” idealism, offers us the poorly historicized, neo-liberal idea of “cultural techniques” courtesy of Cornelia Vismann and Bernhard Siegert (Vismann 2013, 83-93; Siegert 2013, 48-65). This latter is a conveniently deracinated way of conceptualizing the distributed agency of everything techno-human without having to register the abiding fundamental antagonisms, the life and death struggle, in anything. Rather, the question I want to pose about computing is one capable of both foregrounding and interrogating violence, assigning responsibility, making changes, and demanding reparations. The challenge upon us is to decolonize computing. Has the waning not just of affect (of a certain type) but of history itself brought us into a supposedly post-historical space? Can we see that what we once called history, and is now no longer, really has been pre-history, stages of pre-history? What would it mean to say in earnest “What’s past is prologue?”[6] If the human has never been and should never be, if there has been this accumulation of negative entropy first via linear time and then via its disruption, then what? Postmodernism, posthumanism, Flusser’s post-historical, and Berardi’s After the Future notwithstanding, can we take the measure of history?

Techno-Humanist Dehumanization

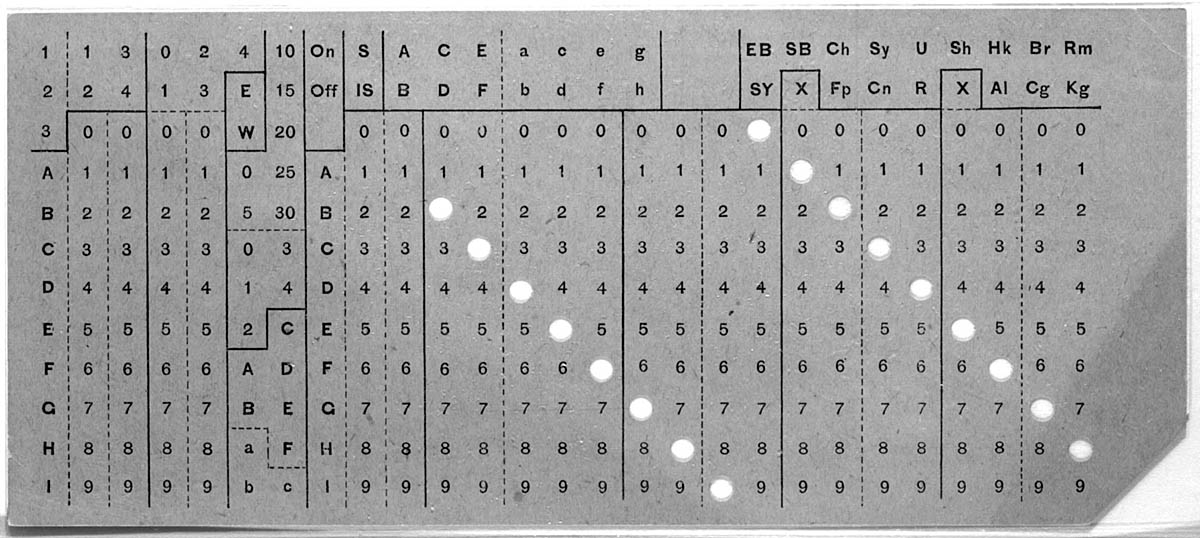

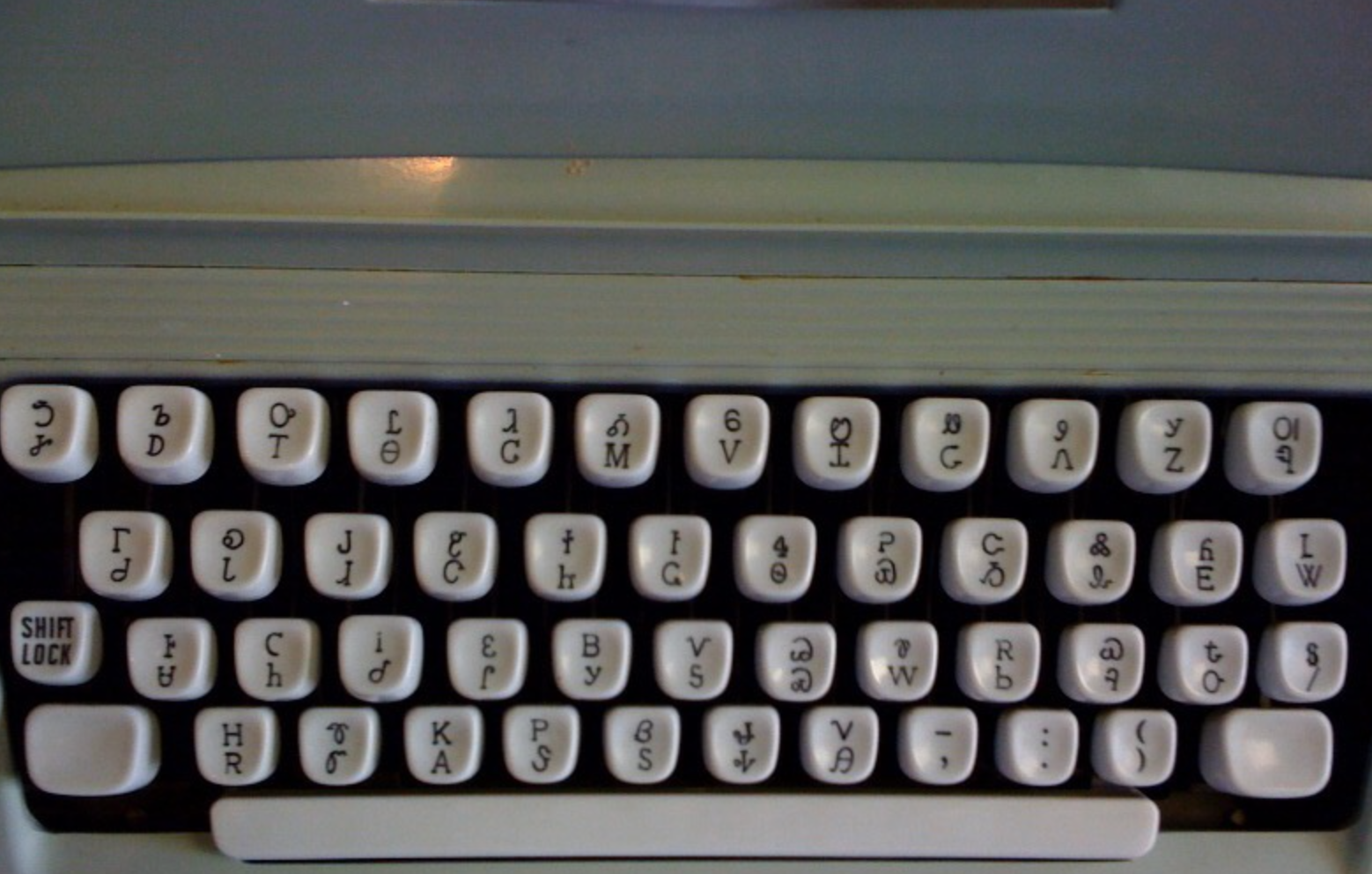

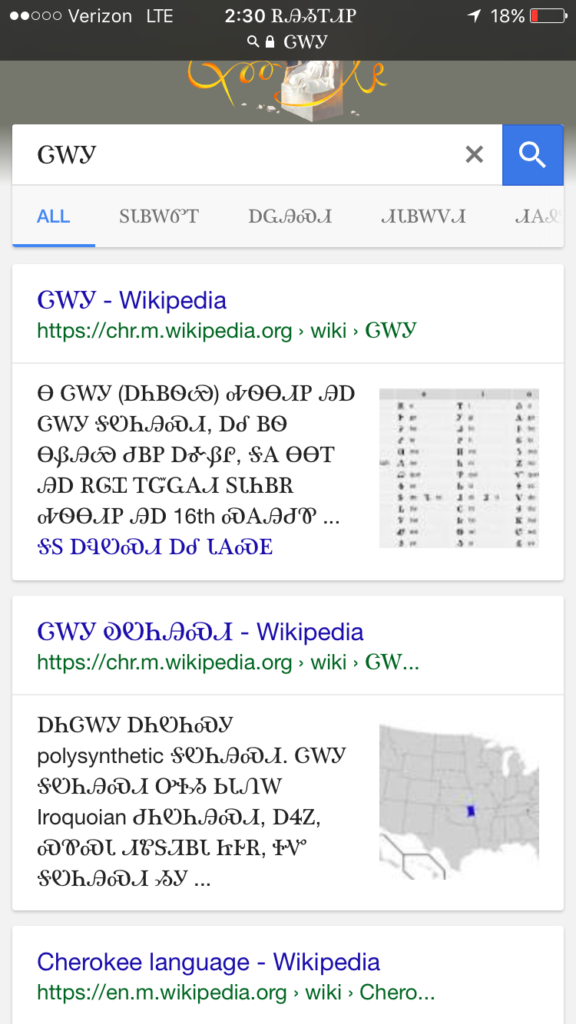

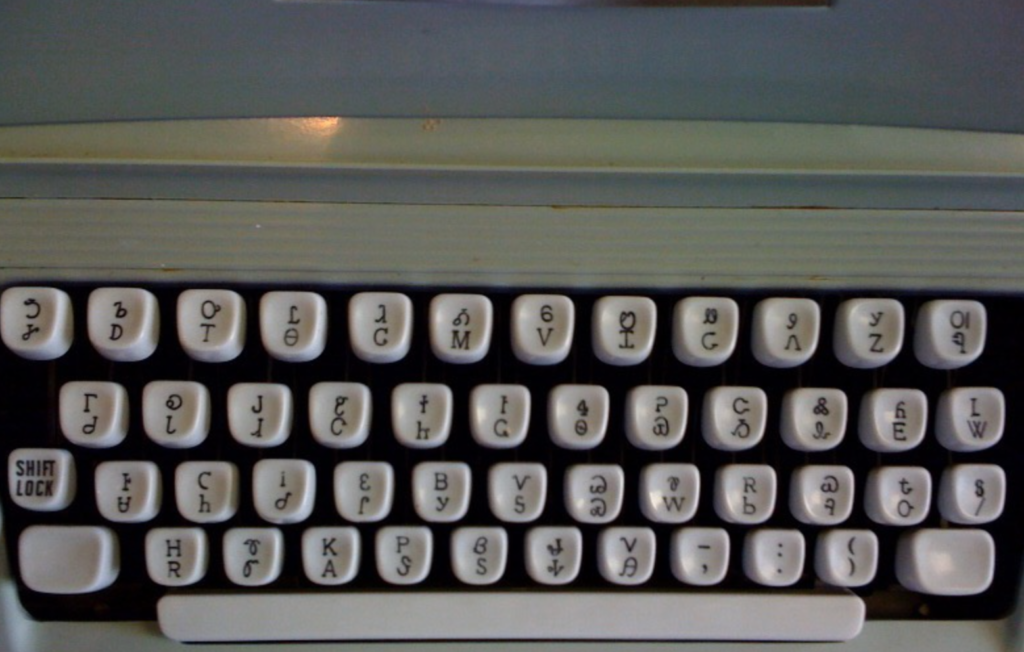

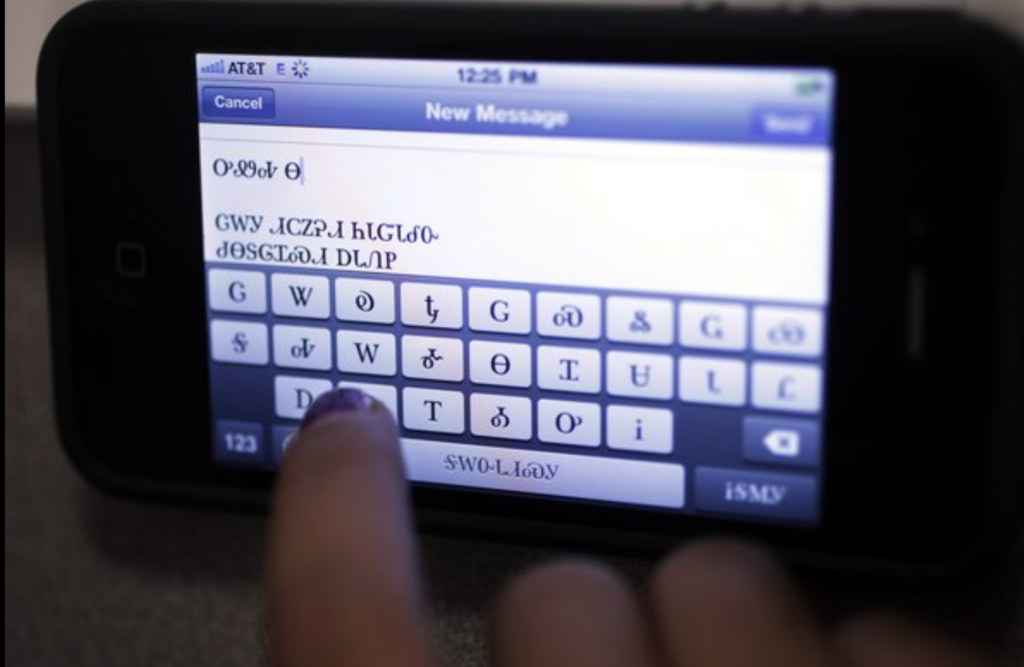

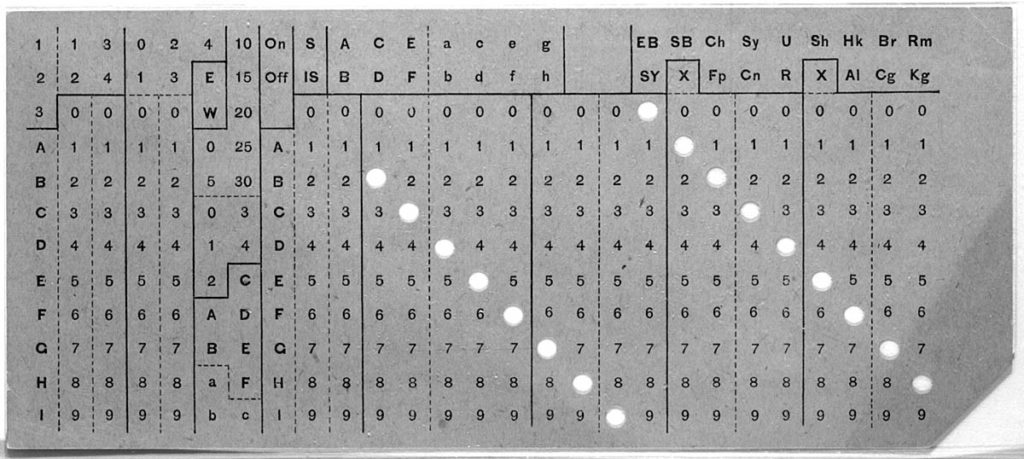

I would like to conclude this essay with a few examples of techno-humanist dehumanization. In 1889, Herman Hollerith patented the punchcard system and mechanical tabulator that was used in the 1890 censuses in Germany, England, Italy, Russia, Austria, Canada, France, Norway, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines. A national census, which normally took eight to ten years now took a single year. The subsequent invention of the plugboard control panel in 1906 allowed for tabulators to perform multiple sorts in whatever sequence was selected without having to be rebuild the tabulators—an early form of programming. Hollerith’s Tabulating Machine Company merged with three other companies in 1911 to become the Computing Tabulating Recording Company, which renamed itself IBM in 1924.

While the census opens a rich field of inquiry that includes questions of statistics, computing, and state power that are increasingly relevant today (particularly taking into account the ever-presence of the NSA), for now I only want to extract two points: 1) humans became the fodder for statistical machines and 2) as Vince Rafael has shown regarding the Philippine census and as Edwin Black has shown with respect to the holocaust, the development of this technology was inseparable from racialization and genocide (Rafael 2000; Black 2001)

Rafael shows that coupled to photographic techniques, the census at once “discerned” and imposed a racializing schema that welded historical “progress” to ever-whiter waves of colonization, from Malay migration to Spanish Colonialism to U.S. Imperialism (2000) Racial fantasy meets white mythology meets World Spirit. For his part, Edwin Black (2001) writes:

Only after Jews were identified—a massive and complex task that Hitler wanted done immediately—could they be targeted for efficient asset confiscation, ghettoization, deportation, enslaved labor, and, ultimately, annihilation. It was a cross-tabulation and organizational challenge so monumental, it called for a computer. Of course, in the 1930s no computer existed.

But IBM’s Hollerith punch card technology did exist. Aided by the company’s custom-designed and constantly updated Hollerith systems, Hitler was able to automate his persecution of the Jews. Historians have always been amazed at the speed and accuracy with which the Nazis were able to identify and locate European Jewry. Until now, the pieces of this puzzle have never been fully assembled. The fact is, IBM technology was used to organize nearly everything in Germany and then Nazi Europe, from the identification of the Jews in censuses, registrations, and ancestral tracing programs to the running of railroads and organizing of concentration camp slave labor.

IBM and its German subsidiary custom-designed complex solutions, one by one, anticipating the Reich’s needs. They did not merely sell the machines and walk away. Instead, IBM leased these machines for high fees and became the sole source of the billions of punch cards Hitler needed (Black 2001).

The sorting of populations and individuals by forms of social difference including “race,” ability and sexual preference (Jews, Roma, homosexuals, people deemed mentally or physically handicapped) for the purposes of sending people who failed to meet Nazi eugenic criteria off to concentration camps to be dispossessed, humiliated, tortured and killed, means that some aspects of computer technology—here, the Search Engine—emerged from this particular social necessity sometimes called Nazism (Black 2001). The Philippine-American War, in which Americans killed between 1/10th and 1/6th of the population of the Philippines, and the Nazi-administered holocaust are but two world historical events that are part of the meaning of early computational automation. We might say that computers bear the legacy of imperialism and fascism—it is inscribed in their operating systems.

The mechanisms, as well as the social meaning of computation, were refined in its concrete applications. The process of abstraction hid the violence of abstraction, even as it integrated the result with economic and political protocols and directly effected certain behaviors. It is a well-known fact that Claude Shannon’s landmark paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” proposed a general theory of communication that was content-indifferent (1948, 379-423). This seminal work created a statistical, mathematical model of communication while simultaneously consigning any and all specific content to irrelevance as regards the transmission method itself. Like use-value under the management of the commodity form, the message became only a supplement to the exchange value of the code. Elsewhere I have more to say about the fact that some of the statistical information Shannon derived about letter frequency in English used as its ur-text, Jefferson The Virginian (1948), the first volume of Dumas Malone’s monumental six volume study of Jefferson, famously interrogated by Annette Gordon-Reed in her Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings: An American Controversy for its suppression of information regarding Jefferson’s relation to slavery (1997).[7] My point here is that the rules for content indifference were themselves derived from a particular content and that the language used as a standard referent was a specific deployment of language. The representative linguistic sample did not represent the whole of language, but language that belongs to a particular mode of sociality and racialized enfranchisement. Shannon’s deprivileging of the referent of the logos as referent, and his attention only to the signifiers, was an intensification of the slippage of signifier from signified (“We, the people…”) already noted in linguistics and functionally operative in the elision of slavery in Jefferson’s biography, to say nothing of the same text’s elision of slave-narrative and African-American speech. Shannon brilliantly and successfully developed a re-conceptualization of language as code (sign system) and now as mathematical code (numerical system) that no doubt found another of its logical (and material) conclusions (at least with respect to metaphysics) in post-structuralist theory and deconstruction, with the placing of the referent under erasure. This recession of the real (of being, the subject, and experience—in short, the signified) from codification allowed Shannon’s mathematical abstraction of rules for the transmission of any message whatsoever to become the industry standard even as they also meant, quite literally, the dehumanization of communication—its severance from a people’s history.

In a 1987 interview, Shannon was quoted as saying “I can visualize a time in the future when we will be to robots as dogs are to humans…. I’m rooting for the machines!” (1971). If humans are the robot’s companion species, they (or is it we?) need a manifesto. The difficulty is that the labor of our “being” such that it is/was is encrypted in their function. And “we” have never been “one.”

Tara McPherson has brilliantly argued that the modularity achieved in the development of UNIX has its analogue in racial segregation. Modularity and encapsulation, necessary to the writing of UNIX code that still underpins contemporary operating systems were emergent general socio-technical forms, what we might call technologies, abstract machines, or real abstractions. “I am not arguing that programmers creating UNIX at Bell Labs and at Berkeley were consciously encoding new modes of racism and racial understanding into digital systems,” McPherson argues, “The emergence of covert racism and its rhetoric of colorblindness are not so much intentional as systemic. Computation is a primary delivery method of these new systems and it seems at best naïve to imagine that cultural and computational operating systems don’t mutually infect one another.” (in Nakamura 2012, 30-31; italics in original)

This is the computational unconscious at work—the dialectical inscription and re-inscription of sociality and machine architecture that then becomes the substrate for the next generation of consciousness, ad infinitum. In a recent unpublished paper entitled “The Lorem Ipsum Project,” Alana Ramjit (2014) examines industry standards for the now-digital imaging of speech and graphic images. These include Kodak’s “Shirley cards” for standard skin tone (white), the Harvard Sentences for standard audio (white), the “Indian Head Test Pattern” for standard broadcast image (white fetishism), and “Lenna,” an image of Lena Soderberg taken from Playboy magazine (white patriarchal unconscious) that has become the reference standard image for the development of graphics processing. Each of these examples testifies to an absorption of the socio-historical at every step of mediological and computational refinement.

More recently, as Chris Vitale, brought out in a powerful presentation on machine learning and neural networks given at Pratt Institute in 2016, Facebook’s machine has produced “Deep Face,” an image of the minimally recognizable human face. However, this ur-human face, purported to be, the minimally recognizable form of the human face turns out to be a white guy. This is a case in point of the extension of colonial relations into machine function. Given the racialization of poverty in the system of global apartheid (Federici 2012), we have on our hands (or, rather, in our machines) a new modality of automated genocide. Fascism and genocide have new mediations and may not just have adapted to new media but may have merged. Of course, the terms and names of genocidal regeimes change, but the consequences persist. Just yesterday it was called neo-liberal democracy. Today it’s called the end of neo-liberalism. The current world-wide crisis in migration is one of the symptoms of the genocidal tendencies of the most recent coalescence of the “practically” automated logistics of race, nation and class. Today racism is at once a symptom of the computational unconscious, an operation of non-conscious cognition, and still just the garden variety self-serving murderous stupidity that is the legacy of slavery, settler colonialism and colonialism.

Thus we may observe that the statistical methods utilized by IBM to find Jews in the Shtetl are operative in Weiner’s anti-aircraft cybernetics as well as in Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system. But, the prevailing view, even if it is not one of pure mathematical abstraction, in which computational process has its essence without reference to any concrete whatever, can be found in what follows. As an article entitled “Traces of Israel’s Iron Dome can be found in Tech Startups” for Bloomberg News almost giddily reports:

The Israeli-engineered Iron Dome is a complex tapestry of machinery, software and computer algorithms capable of intercepting and destroying rockets midair. An offshoot of the missile-defense technology can also be used to sell you furniture. (Coppola 2014)[8]

Not only is war good computer business, it’s good for computerized business. It is ironic that te is likened to a tapestry and now used to sell textiles – almost as if it were haunted by Lisa Nakamura’s recent findings regarding the (forgotten) role of Navajo women weavers in the making of early transistor’s for Silicon Valley legend and founding father, as well as infamous eugenicist, William Shockley’s company Fairchild.[9] The article goes on to confess that the latest consumer spin-offs that facilitate the real-time imaging of couches in your living room capable of driving sales on the domestic fronts exist thanks to the U. S. financial support for Zionism and its militarized settler colonialism in Palestine. “We have American-backed apartheid and genocide to thank for being able to visualize a green moderne couch in our very own living room before we click “Buy now.”” (Okay, this is not really a quotation, but it could have been.)

Census, statistics, informatics, cryptography, war machines, industry standards, markets—all management techniques for the organization of otherwise unruly humans, sub-humans, posthumans and nonhumans by capitalist society. The ethos of content indifference, along with the encryption of social difference as both mode and means of systemic functionality is sustainable only so long as derivative human beings are themselves rendered as content providers, body and soul. But it is not only tech spinoffs from the racist war dividends we should be tracking. Wendy Chun (2004, 26-51) has shown in utterly convincing ways that the gendered history of the development of computer programming at ENIAC in which male mathematicians instructed female programmers to physically make the electronic connections (and remove any bugs) echoes into the present experiences of sovereignty enjoyed by users who have, in many respects, become programmers (even if most of us have little or no idea how programming works, or even that we are programming).

Chun notes that “during World War II almost all computers were young women with some background in mathematics. Not only were women available for work then, they were also considered to be better, more conscientious computers, presumably because they were better at repetitious, clerical tasks” (Chun 2004, 33) One could say that programming became programming and software became software when commands shifted from commanding a “girl” to commanding a machine. Clearly this puts the gender of the commander in question.

Chun suggests that the augmentation of our power through the command-control functions of computation is a result of what she calls the “Yes sir” of the feminized operator—that is, of servile labor (2004). Indeed, in the ENIAC and other early machines the execution of the operator’s order was to be carried out by the “wren” or the “slave.” For the desensitized, this information may seem incidental, a mere development or advance beyond the instrumentum vocale (the “speaking tool” i.e., a roman term for “slave”) in which even the communicative capacities of the slave are totally subordinated to the master. Here we must struggle to pose the larger question: what are the implications for this gendered and racialized form of power exercised in the interface? What is its relation to gender oppression, to slavery? Is this mode of command-control over bodies and extended to the machine a universal form of empowerment, one to which all (posthuman) bodies might aspire, or is it a mode of subjectification built in the footprint of domination in such a way that it replicates the beliefs, practices and consequences of “prior” orders of whiteness and masculinity in unconscious but nonetheless murderous ways.[10] Is the computer the realization of the power of a transcendental subject, or of the subject whose transcendence was built upon a historically developed version of racial masculinity based upon slavery and gender violence?

Andrew Norman Wilson’s scandalizing film Workers Leaving the Googleplex (2011), the making of which got him fired from Google, depicts lower class, mostly of color workers leaving the Google Mountain View campus during off hours. These workers are the book scanners, and shared neither the spaces nor the perks with Google white collar workers, had different parking lots, entrances and drove a different class of vehicles. Wilson also has curated and developed a set of images that show the condom-clad fingers (black, brown, female) of workers next to partially scanned book pages. He considers these mis-scans new forms of documentary evidence. While digitization and computation may seem to have transcended certain humanistic questions, it is imperative that we understand that its posthumanism is also radically untranscendent, grounded as it is on the living legacies of oppression, and, in the last instance, on the radical dispossession of billions. These billions are disappeared, literally utilized as a surface of inscription for everyday transmissions. The dispossessed are the substrate of the codification process by the sovereign operators commanding their screens. The digitized, rewritable screen pixels are just the visible top-side (virtualized surface) of bodies dispossessed by capital’s digital algorithms on the bottom-side where, arguably, other metaphysics still pertain. Not Hegel’s world spirit—whether in the form of Kurzweil’s singularity or Tegmark’s computronium—but rather Marx’s imperative towards a ruthless critique of everything existing can begin to explain how and why the current computational eco-system is co-functional with the unprecedented dispossession wrought by racial computational capitalism and its system of global apartheid. Racial capitalism’s programs continue to function on the backs of those consigned to servitude. Data-visualization, whether in the form of selfie, global map, digitized classic or downloadable sound of the Big Bang, is powered by this elision. It is, shall we say, inescapably local to planet earth, fundamentally historical in relation to species emergence, inexorably complicit with the deferral of justice.

The Global South, with its now world-wide distribution, is endemic to the geopolitics of computational racial capital—it is one of its extraordinary products. The computronics that organize the flow of capital through its materials and signs also organize the consciousness of capital and with it the cosmological erasure of the Global South. Thus the computational unconscious names a vast aspect of global function that still requires analysis. And thus we sneak up on the two principle meanings of the concept of the computational unconscious. On the one hand, we have the problematic residue of amortized consciousness (and the praxis thereof) that has gone into the making of contemporary infrastructure—meaning to say, the structural repression and forgetting that is endemic to the very essence of our technological buildout. On the other hand, we have the organization of everyday life taking place on the basis of this amortization, that is, on the basis of a dehistoricized, deracinated relation to both concrete and abstract machines that function by virtue of the fact that intelligible history has been shorn off of them and its legibility purged from their operating systems. Put simply, we have forgetting, the radical disappearance and expunging from memory, of the historical conditions of possibility of what is. As a consequence, we have the organization of social practice and futurity (or lack thereof) on the basis of this encoded absence. The capture of the general intellect means also the management of the general antagonism. Never has it been truer that memory requires forgetting – the exponential growth in memory storage means also an exponential growth in systematic forgetting – the withering away of the analogue. As a thought experiment, one might imagine a vast and empty vestibule, a James Ingo Freed global holocaust memorial of unprecedented scale, containing all the oceans and lands real and virtual, and dedicated to all the forgotten names of the colonized, the enslaved, the encamped, the statisticized, the read, written and rendered, in the history of computational calculus—of computer memory. These too, and the anthropocene itself, are the sedimented traces that remain among the constituents of the computational unconscious.

_____

Jonathan Beller is Professor of Humanities and Media Studies and Director of the Graduate Program in Media Studies at Pratt Institute. His books include The Cinematic Mode of Production: Attention Economy and the Society of the Spectacle (2006); Acquiring Eyes: Philippine Visuality, Nationalist Struggle, and the World-Media System (2006); and The Message Is Murder: Substrates of Computational Capital (2017). He is a member of the Social Text editorial collective..

_____

Notes

[1] A reviewer of this essay for b2o: An Online Journal notes, “the phrase ‘digital computer’ suggests something like the Turing machine, part of which is characterized by a second-order process of symbolization—the marks on Turing’s tape can stand for anything, & the machine processing the tape does not ‘know’ what the marks ‘mean.’” It is precisely such content indifferent processing that the term “exchange value,” severed as it is of all qualities, indicates.

[2] It should be noted that the reverse is also true: that race and gender can be considered and/as technologies. See Chun (2012), de Lauretis (1987).

[3] To insist on first causes or a priori consciousness in the form of God or Truth or Reality is to confront Marx’s earlier acerbic statement against a form of abstraction that eliminates the moment of knowing from the known in The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844,

Who begot the first man and nature as a whole? I can only answer you: Your question is itself a product of abstraction. Ask yourself how you arrived at that question. Ask yourself it that question is not posed from a standpoint to which I cannot reply, because it is a perverse one. Ask yourself whether such a progression exists for a rational mind. When you ask about the creation of nature and man you are abstracting in so doing from man and nature. You postulate them as non-existent and yet you want me to prove them to you as existing. Now I say give up your abstraction and you will give up your question. Or, if you want to hold onto your abstraction, then be consistent, and if you think of man and nature as non-existent, then think of yourself as non-existent, for you too are surely man and nature. Don’t think, don’t ask me, for as soon as you think and ask, your abstraction from the existence of nature and man has no meaning. Or are you such an egoist that you postulate everything as nothing and yet want yourself to be?” (Tucker 1978, 92)

[4] If one takes the derivative of computational process at a particular point in space-time one gets an image. If one integrates the images over the variables of space and time, one gets a calculated exploit, a pathway for value-extraction. The image is a moment in this process, the summation of images is the movement of the process.

[5] See Harney and Moten (2013). See also Browne (2015), especially 43-50.

[6] In practical terms, the Alternative Informatics Association, in the announcement for their Internet Ungovernance Forum puts things as follows:

We think that Internet’s problems do not originate from technology alone, that none of these problems are independent of the political, social and economic contexts within which Internet and other digital infrastructures are integrated. We want to re-structure Internet as the basic infrastructure of our society, cities, education, heathcare, business, media, communication, culture and daily activities. This is the purpose for which we organize this forum.

The significance of creating solidarity networks for a free and equal Internet has also emerged in the process of the event’s organization. Pioneered by Alternative Informatics Association, the event has gained support from many prestigious organizations worldwide in the field. In this two-day event, fundamental topics are decided to be ‘Surveillance, Censorship and Freedom of Expression, Alternative Media, Net Neutrality, Digital Divide, governance and technical solutions’. Draft of the event’s schedule can be reached at https://iuf.alternatifbilisim.org/index-tr.html#program (Fidaner, 2014).

[7] See Beller (2016, 2017).