I have experienced Mandela as a presence, an absence, and a label.

During the historic first free elections in Tunisia, held on October 23, 2011, I voted early, then set off to tour the polling stations in my hometown of Kasserine, a neglected and rebellious part of the country that brought the Tunisian revolution to sharp pitch early in January of the same year. The mood was buoyant, and long queues of determined men and women had already formed. I took lots of photos to mark the moment but also to tell the story when I got back to Oxford. But when I wanted to express what the elections were like on my Facebook page, my mind went back to one picture I have had in my office in the United States and in the United Kingdom for many years. It was an AP photo of two Zulu women carrying an infirm friend to the voting station in Usuthu, in the Natal Province of South Africa, on April 26, 1994. Their determination and hope was galvanized by Mandela. Those images and the inspired hope that fed them had stayed with me until the day when that “Mandela moment” came to North Africa, fifteen years later.

The elections were part of a continuing transitional phase in Tunisia. After several traumatic decades, the country sorely needed reconciliation and healing. But for all the good will, active civil society, several conferences, money, and speeches, Tunisia risks either failing its transitional justice, and reproducing structures of authoritarianism, or being torn apart, like Syria, Egypt, and Libya. Throughout this period, three years now, I kept thinking that what we needed was a Nelson Mandela of our own. We missed having a national hero, a father figure, a reassuring face, a man of consensus able to forgive and inspire feelings of genuine leadership in reconciliation and healing. Mandela seems to have set a model for transitional justice that the Arab revolutions need at this moment. For cultures and societies that have been ruled by strong men and have been internalizing models of authoritarian power, a revolution has been a welcome leveling of authority. But at the same time, the atomization of the scene among numerous parties and figures of limited appeal and influence, as well as the return of harmful and fractious identity politics, left people without a moral force that could broker differences and show the way, the Mandela way. But then again, the Arab revolutions may have shown how specific to South Africa Mandela has been and how difficult his example was to transfer or to emulate.

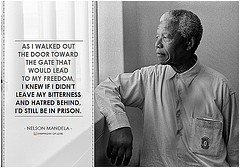

Mandela had indeed been an inspiration to many Tunisian progressives in the student and labor movements for decades before 2011. But things being what they are in the market machine, Mandela has become an iconic image and therefore consumed and misquoted at will. The wide dissemination of this image made it inevitable that local versions of Mandela would be invented and circulated, regardless of how flimsy resemblances may be. But for me, the peak of this instrumentalization saw a figure of Islamism in Tunisia, someone who did so much to divide the country and erode its modernity and freedoms before and after the revolution, dubbed “the closest thing to an Islamic Nelson Mandela.” Aside from the absurdity of the phrase “Islamic Mandela,” the label was conferred on Rachid Ghannouchi, by an American “expert” and Harvard academic keen on pushing two agendas that could not be furthest from Mandela’s ideals. The first was developed in Iraq and driven by dreams of reconquest and repartition of the Middle East, led by Bush Junior. The second points to the desperate need “experts” and pundits felt to assign leaders to Arab revolutions and anoint political Islam at the helm. Mandela has become, then, a convenient metaphor at the service of grotesque opportunism to usurp the ideals of Arab revolutions.

-Mohamed-Salah Omri