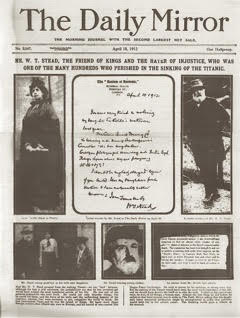

Journalists might be chroniclers of the present, but two decades of books, conferences, symposia, interviews, talks, special issues, and end-of-year features on the future of news suggests they are also preoccupied with what lies ahead. Still, few of today’s media workers are as prescient as William T. Stead, the English journalist and amateur occultist who came close to predicting the 1912 Titanic disaster twenty years before he died in it. In his 1893 short story, “From the Old World to the New,” a transatlantic ocean liner collides with an iceberg and erupts in flames, leaving the vessel’s desperate passengers clinging to a sheet of ice. Unlike the Titanic, everyone in the story lives. Two passengers on a nearby ship receive telepathic distress signals. One has haunting visions of the accident in her sleep, and the other finds a written plea for help in the handwriting of a friend travelling aboard the sinking ship. The clairvoyants relay this information to their captain, who steers a perilous course through the icebergs and rescues the shipwrecked passengers. In 1893 wireless telegraphy, the early term for radio, did not yet exist (even if, as an idea, it electrified the Victorian imagination). By the time of the Titanic’s maiden voyage, radio was a standard maritime communication device. The technology helped, but was no panacea: the closest ship to receive the Titanic’s SOS signals arrived too late for Stead and many of his fellow passengers.

Stead was at the forefront of thinking about new technologies as well as his own demise. He also had a keen interest in journalism’s future, one shared by many of today’s news workers. Even people who failed to predict the collision of twentieth-century news models with the Web are now regularly called upon to forecast the profession’s future. Answering the future-of-news question requires experts to project past experience and current knowledge onto a forthcoming period of time. But does this question have a history of its own? Did earlier news workers prognosticate as often and with the same urgency? What anxieties or opportunities provoked past future thought? To answer these questions, I explore some future-oriented predictions, assessments, and directives of nineteenth and twentieth-century reporters, editors, and media entrepreneurs in the United States and England. Their claims about the future of journalism serve as windows into the relationship between technology and news work at different historical moments and offer insights into today’s prognoses.

The Current Crisis

In the U.S., mainstream news agencies have been dealt a series of technological, economic, and political blows that have changed the way news is written, distributed, consumed, funded, and understood. Anxiety about the future can be understood in light of three interrelated challenges to the post-World War II information order: twenty years of digital technological disruption, the 2008 economic crisis, and politically and economically motivated challenges to the industrial news media.

By now it is a truism that screen-based digital technologies have transformed journalism. Newspapers, in particular, have experienced an advertising and readership decline more existentially threatening than the threat posed to print from radio in the 1920s or from television in the 1950s. The net presented a challenge to print media even before it became a major platform for news; in the mid-1990s, Craigslist disrupted the long-standing classified ad revenue streams of daily papers and newspapers (Seamans and Zhu 2013). The incorporation of print news functions into the digital has only intensified since then. Internet saturation in U.S. households is at 84 percent and climbing (Pew Research Center 2015). News consumers are no longer tethered to a small set of news organizations; sixty-two percent read disparate stories they happen across on social media and Twitter feeds and do not subscribe to a single newspaper or news magazine (Gottfried and Shearer 2016).

Newspapers were already on shaky ground when the 2008 financial crisis struck. Economic downturn coupled with technological displacement led to a crisis of near Darwinian proportions for an industry that had seen outsized profit margins for much of the twentieth century. Closures, bankruptcies, and mergers ensued. Historic papers like the Rocky Mountain News and Ann Arbor News shut their doors, and many other dailies and weeklies reverted to web-only formats (Rogers 2009). Over a hundred papers ceased publication between 2004 and 2016 (Barthel 2016). Papers that endured the techno-economic struggles of the 2000s had to rethink the nature of the news enterprise from the ground up, devising survival strategies in a new Mad Max-style advertising and subscriber-depleted media terrain.

Journalism never regained its footing after the financial crisis. As a Pew Research Center study suggests, “2015 might as well have been a recession year” for the traditional news media (Barthel 2016). The study paints a grim picture of the news industry. In 2014 and 2015, the number of print media consumers continued to drop. Even revenue from digital ads fell as advertisers migrated to social media sites like Facebook. And full-time jobs in journalism continued their steady decline: today there are 39 percent fewer positions than there were two decades ago. News consumption also began to shift from personal computers to mobile devices. Readers increasingly access news items on their phones, while standing in line, waiting at red lights, and at other spare moments of the day. In a metric-driven world, mobile news consumption has a silver lining: many sites are receiving more visits than before. However, the average mobile-device reader spends less time with each article than they did on PCs (Barthel 2016). Demand for news exists, albeit in ever-smaller and dislocated chunks.

At the same time, insurgent news entrepreneurs have altered the media field by leveraging weaknesses in the system and taking advantage of emerging technological possibilities. Just as the most successful nineteenth-century “startups” were enabled by new technologies like the steam press that sped up and lowered the cost of printing,[1] today’s media insurgents – people like Matt Drudge, Steve Bannon, the late Andrew Brietbart, and others – moved straight to digital news and data formats without prior institutional baggage. Since initial start-up costs on the Web are low and news production and dissemination is relatively easy, they were able to offer a trimmed-down model of news production that did not require reporting in the strict sense.

Some of these insurgents imagine a future for news unfettered by past or existing structures. They claim they want to take a sledgehammer to old media, but it really serves as their foil. In the current context, the terms old media, establishment media, and mainstream media are thrown around by new media players jockeying for position in a changing media field. The White House is currently engaged in a hostile yet mutually beneficial battle with mainstream news outlets, and it echoes the position that the news media is a liberal monolith that censors alternative positions.[2] At the same time, establishment journalism is enjoying a period of unpredicted growth due to the Trump bubble, and has been reinventing and reimagining itself as the Fourth Estate in the wake of the 2016 election.

Future-of news experts reduce professional and public uncertainty in times of flux (Lowery and Shan, 2016). But it is important to note that not all contemporary observers are worried. The late David Carr, for instance, believed Web startups like Buzzfeed would eventually become more like traditional news outlets. “The first thing they do when they get a little money is hire some journalists,” he said in 2014. He was confident news audiences had an intrinsic desire for quality and that the business end of things would eventually sort itself out.

Similarly, people who express anxieties about the state of journalism are more likely to have experienced journalism as a stable and predictable field, and to have lost something when the old model collapsed. Those who are concerned worry that a digital-age business model will never arise to solve journalism’s funding problem. They worry that automation will replace journalists. They fear ideological bubbles and distracted audiences. They lament eroding legitimacy and credibility in an era of so-called fake news. And they hope prognosticators possess special knowledge or have more crystalline vision than others in the profession. But did past reporters and editors worry about the fate of their profession in the same way?

The Nineteenth Century

In the nineteenth century, journalism was a wide-open, experimental field on both sides of the Atlantic. Literacy rates were climbing. Print technologies had improved. Paper was cheaper to produce than ever before. Newspapers, book publishers, and the public were experiencing the power of mass dissemination. By the second half of the nineteenth century, newspapers’ social standing had improved. Some observers believed they were institutions on the ascent that would eventually play a social role on par with educators, clergy, or government officials.

However, concerns about the accelerated pace of newspaper work, the constant demand for “newness,” and the unremitting imperative to scoop rival papers were refrains in nineteenth-century journalistic commentary. In his biography of Henry Raymond, the journalist and author Augustus Maverick characterized news work in 1840s New York as an unceasing “treadmill”:

Only those who have been placed upon the treadmill of a daily newspaper in New York know the severity of the strain it imposes on the mental and physical powers. ‘There is no cessation,’ one newsman explained. ‘A good newspaper never publishes that which is technically denominated ‘old news,’ – a phrase so significant in journalism as to be invested with untold horrors. All must be daily fresh, daily complete, daily polished and perfect; else the journal falls into disrepute, is distanced by its rivals, and, becoming ‘dull,’ dies. (1870, 220)

I will return to the issue of acceleration later in the paper. For now, it is important to note that perceptions of speedup and fears of being outmoded were embedded in the experience of journalism as early as the 1840s.

Despite journalism’s daily stresses, Maverick felt the quality and legitimacy of papers was on the rise. The press had successfully overcome early-nineteenth century threats to credibility like partisanship and the sensationalism of the penny press, which printed fantastical, fabricated stories like the New York Sun’s Great Moon Hoax. Maverick believed this progress would continue unabated:

Accepting the promise of the Present, the prospect of the Future brightens. For, as men come to know each other better, through the rapid annihilation of time and space, they will be plunged deeper into affairs of trade and finance and commerce, and be burdened with a thousand cares, – and the Press, as the reflector of the popular mind, will then take a broader view, and reach forth towards a higher aim; becoming, even more than now, the living photograph of the time, the sympathetic adviser, the conservator, regulator, and guide of American society. (1870, 358)

Maverick envisioned a future in which the press would both facilitate and temper the social changes wrought by connectivity (changes that he analyzed in his 1858 book on the telegraph).

The same year Maverick predicted a role for the press as guide and advisor in an increasingly complex and interconnected world, William T. Stead began his career as a fledgling reporter. Few journalists tested, challenged, and wielded the power of the press quite like Stead. In his essay “The Future of Journalism” (1887), he envisioned radical and expansive new plans for the press. His own journalistic experiments had convinced him that editors “could become the most permanently influential Englishmen in the Empire.” But to ascend to this level one had to become a “master of the facts – especially the most dominant fact of all, the state of public opinion.” Editors guessed at public opinion, but had no way of gauging it. To remedy this, Stead suggested journalists be allowed twenty-four hour access to everyone “from the Queen downward.” His news workers of the future would be intimately connected to public opinion across the social system. They would have unfettered access to powerful people, which would diminish the unquestioned authority and privacy of the aristocracy.

Since the system Stead imagined would be impossible for one person to manage, it would be held in place by travelers who would preach the importance of journalistic work with a missionary zeal. The travelers would eventually be “entrusted the further and more delicate duty of collecting the opinions of those who form the public opinion of their locality.” Stead was certain the enactment of his plan would result in the greatest “spiritual and educational and governing agency which England has yet seen.”

“The Future of Journalism” demonstrates a keen awareness of print’s power in an era of mass distribution and rapid news diffusion. It was grandiose because it imagined a far greater political role for journalists than they would ever possess. In some respects, though, Stead was a superior prognosticator. In 1887, the communications field was undifferentiated. His journalistic travelers and major-generals would ultimately manifest themselves in the twentieth century as pollsters, social scientists, and public relations specialists. But the editor would not sit at the helm, overseeing these efforts. Instead, journalist/editors would report their findings and beliefs, and serve as conduits in the flow of ideas between these professionals and the public. Despite their inadequacies, Stead’s writings on the future were more prescriptive and imaginative than many of today’s commentaries on the topic.

Twentieth-Century Futures

Nineteenth-century commentators on the news profession lamented acceleration, railed against partisanship, and decried certain forms of sensationalism, but they also believed in progress. This changed in the twentieth century. Frank Munsey’s career began by selling low-cost magazines and pulp fiction. In 1889 he launched the popular general-interest magazine Munsey’s Magazine, and he went on to amass a fortune between 1900 and 1920 purchasing and selling ten different newspapers, including The New York Daily News, The Boston Journal, and The Washington Times. He was a businessman first and journalist second. Munsey’s contemporaries viewed him as journalism’s undertaker: his very appearance on the scene heralded a newspaper’s demise. His contemporary, Oswald Garrison Villard, described him as “a dealer in dailies – little else and little more” (1923, 81).[3]

Munsey’s “Journalism of the Future” appeared in 1903 in Munsey’s Magazine. In it, he suggests that the common editors’ refrain about “lack of good men” misses the real problem. The threat facing journalism is not a lack of well-trained workers, but the size of daily papers. Newspapers, which had been expanding since the 1890s, contained more sections, lengthier features, and larger Sunday editions than ever before. As papers grew, readers became rushed. The problem with news circa 1903 was that there was too much to write about and too much to read. Because they had to absorb so much, readers’ attention was at all all-time low (a concern that resonates with today’s news producers). For Munsey, the solution to the problem of the rushed and inattentive reader lay in condensation and conglomeration. Predicting extreme media consolidation long before it occurred, Munsey speculated that within four years (i.e., by 1907) the entire media field would be whittled down to three or four firms that would publish every newspaper, periodical, magazine, and book:

The journalism of the future will be of a higher order than the journalism of the past or the present. Existing conditions of competition and waste, under individual ownership, make the ideal newspaper impossible. But with a central ownership big enough and strong enough to encompass the whole country, our newspapers can afford to be independent, fearless, and honest. (1903, 830)

For Munsey, consolidation, quality, and independence are linked through the efficiency and scope of large-scale production and the nationalization of mass audiences. He does not foresee problems caused by monopolization or threats to newspapers from radio. He imagines technology only as it relates to its effects on the productive capacity of print news, which he thought was fettered by local ownership.

Writing during World War I, Willard Grosvenor Bleyer, founder of the University of Wisconsin journalism school and advocate of professional training, took a more modest view of journalism’s future. His primary concern was wartime press censorship and the spread of propaganda through semi-official news agencies. However, he considered these developments temporary deviations from the normal function of the press in a democratic society: eventually the profession would return to its pre-war normalcy. “The world war,” he wrote, “has given rise to peculiar problems, none of which, however, seems likely to have permanent effects on our newspapers” (1918, 14). Wartime austerity, especially the high price of paper, posed problems for the news industry. But there was a bright side. People wanted news from Europe, so the higher cost of newspapers had not decreased circulation rates.

Some early-twentieth century observers were concerned about sensationalism and editorial independence or the effects of war on the press, while others worried about the future of democracy in the context of Munsey-wrought newspaper industry mergers. Oswald Villard, writer for The Nation and The NY Evening Post, founder of the American Anti-Imperialist League, and the first treasurer of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, argued that consolidation threatened democracy. Most newspapers lacked commercial independence and were beholden to advertisers who limited what they could publish. He was also concerned about the political implications of audience fragmentation: “Not today can one, no matter how trenchant their pen, be in a garret and expect to reach the conscience of a public by seventy millions larger than the America of Garrison and Lincoln.” Villard, however, held out hope that the views of ‘great men’ would find an audience, even if it meant bypassing the press. He did not predict new media forms, but looked back at old ones: “the prophet of the future will make his message heard, if not by a daily, then by a weekly; if not by a weekly, then by pamphleteering in the manner of Alexander Hamilton; if not by pamphleteering then by speech in the market-place” (1923, 315).

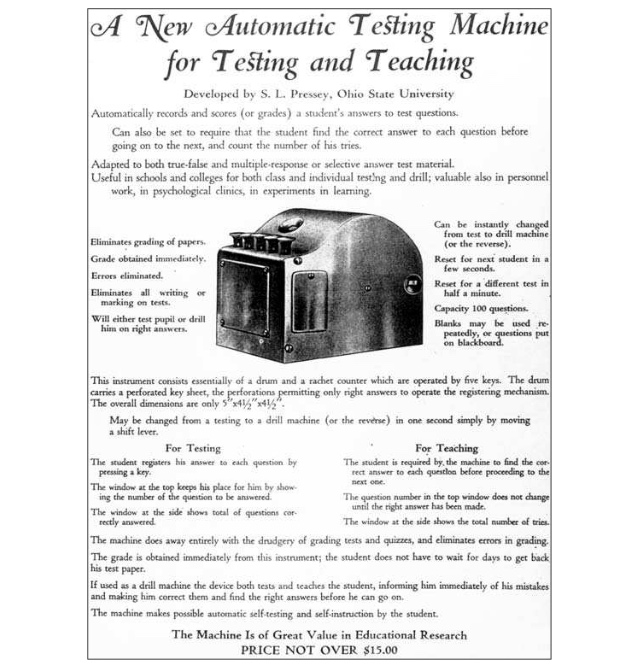

After World War II, journalism experienced a period of stability that gave it an aura of permanence, as if media institutions were constants amidst other economic, social, and cultural changes. Future concerns during this period centered on issues of technology and media consolidation. In 1947, for example, the Hutchins Commission on Freedom of the Press predicted that newspapers would soon be sent from FM radio stations to personal facsimile machines. These devices would print, fold, and deposit them in the hands of U.S. householders each morning (34-45). News workers and industry analysts predicted that technologies as diverse as citizens band radio, cable TV, camcorders, and CD ROMS would, for better or worse, alter the production or consumption of news and either enhance or impede democratic processes (Curran 2010a). In the 1980s and 90s, journalists and media critics pointed to the pernicious effects of monopolization in national and regional markets. They feared the one-newspaper town and the absorption of local newspapers by media franchises. Michael Kinsley recalls that, in the pre-Internet period, “at symposia and seminars on the Future of Newspapers, professional worriers used to worry that these monopoly or near-monopoly newspapers were too powerful for society’s good” (2014).

Time, Space, and Journalism

Time is not a natural resource that springs from the Earth, but a cultural and social construct imagined and experienced in multiple ways (Fabien 1983).[4] Some social theorists argue that the sensation of rapid acceleration is a key feature of the modern experience of time (Crary 2013; Rosa 2013). Harmut Rosa, for example, has argued that time compression has reached a point where the hamster wheel or treadmill has become an apt metaphor for modern life. Work speedups and technological immersion are necessary just to maintain social stasis, without the possibility of advancement or breaking free (Rosa 2010). For Rosa and other accelerationists, acceleration leaves you mired in the present, anticipating the future with a sense of dread. The reality is that there is no uniform experience of time; our experience depends upon our position within circuits of information and capital (Sharma 2014). But when it comes to technological and economic speedup, journalism may be the canary in the mine. Reporters like Maverick experienced this treadmill effect as early as the 1840s. In 1918, Francis Leupp described the quickening pace of news work in the electric age:

We must reckon with the progressive acceleration of the pace of our 20th century life generally. Where we walked in the old times we run in these; where we ambled then, we gallop now. In the age of electric power, high explosives, articulated steel frames, in the larger world; of the long-distance telephone, the taxicab, and the card-index, in the narrower. The problem of existence is reduced to terms of time-measurement. (39)

Like Maverick, Leupp experienced the dynamism of modern life and the dual pressures of accuracy and speed in journalism.

It makes sense that journalism would experience the present this way. As the quintessential modern form, news embodies planned obsolescence (Schwartz 1999). Journalism has undergone two centuries of shrinking intervals of newness and relevance: six-months, a week, a day, an hour. With the rise of social media and Twitter, the intervals between news cycles have grown even shorter. In the twentieth century, edition release times and broadcast schedules helped carve the day into identifiable units with firm deadlines. But in a context where news can be posted around the clock and updated every minute, the clock is no longer a structuring device for journalism. Minutes, seconds, and the calendar click-over from one day to the next are the only salient units of time. News stories that were relevant and new last week often seem ancient a week later. A newsworthy event like President Trump pulling out of the Paris climate agreement can feel as distant as the Vietnam War the following week. New communication forms like Twitter coupled with strategies of disinformation and the routinization of scandal shatter perceptions of continuity. What we are experiencing now is not the death of history, as was proclaimed after the fall of the Berlin Wall, but the death of the present. In news, rapid acceleration has amnestic effects, similar to the experience of sleep deprivation.

If the main time/space vectors in journalism used to be deadlines and beats, the latter may also be losing their importance, giving way to a more fluid cut-and-run style of journalism. For example, the Washington Post’s Chris Cilizza suggests that young reporters should not decline stories saying, “that’s not my beat” (2016). Rather, in a context of dwindling opportunities, journalists should pursue any story available, whether or not it fits into the old-fashioned logic of beat work or the range of competence of individual journalists.[5] But while traditional beats may be losing their cogency, reporters must add a new online “beat” to their repertoire that entails close surveillance of social media and online news, a dynamic that some critics have argued creates a house of mirrors effect in the news industry (Reinemann and Baugut 2013).

Technology and Uncertainty in the Professions

Journalism may be the paradigmatic case of a profession imperiled by a new technology, but its concerns about time and technological displacement cannot be generalized to other spheres. Take lawyers, social workers, and physicians. Uncertainty within the legal profession is largely unrelated to the digital. It was caused by the recent financial crisis coupled with the overtraining of new professionals. Jobs for newly minted JDs evaporated during the recession, leading to a decline in the number of law school applicants after 2010. With enrollment down, the future of smaller law schools became uncertain, and many schools lowered admission standards to stay afloat (Olson 2015; Pistone and Horn 2016). The profession has been in crisis, but not because of the Internet, and there is even some evidence that law positions are coming back (Solomon 2015). Uncertainty for social workers began even earlier, when the Clinton administration began dismantling the welfare state. Despite the obvious need for such professionals, government, non-profit, and other social service jobs have seen a quarter-century decline because of deep budgetary cuts that began in the 1990s (Reisch 2013).

Physicians seem least concerned with the future. They worry more about burnout than they do the fate of their profession. The future is typically invoked in discussions about labor shortages and descriptions of new developments at the intersection of medicine and technology. Articles on the future of medicine routinely tout new developments like 3D printers that can form living cells into new organs (Mellgard 2015). Digitalization has changed many aspects of medicine: electronic medical records and charting alters the way nurses and physicians access information, for instance. But it has not led to credible speculation about replacing physicians with bots. Contrast this with some news workers’ worries about replacement by computer programs like Automated Insight’s narrative generation system, Wordsmith. The Associated Press now employs Wordsmith to do its quarterly earnings reports and other stories, and has become so confident in these auto-generated stories that it runs many of them without prior vetting (the rare human-edited AI story is said to have had “the human touch”) (Miller 2015). Nor have drones been proposed as a viable alternative to human physicians, as they have been for newsgatherer/photojournalists (Etzler 2016).[6]

In none of these other cases is technology the primary motor of destabilization. The character of future angst in the professions, therefore, is occupation dependent. And journalism, it seems, is uniquely sensitive and vulnerable to technology. Every widely-adopted communications technology – the steam press, radio, the net – has restructured news and led to audience expansion or contraction. In this sense, there is nothing new to journalist’s dependence on and transformation by technologies. The one constant is that journalists work in a field of technological contingency.

Conclusion: Euphoria and Dysphoria in Journalism

Visions of the future are also statements about the present. Political and economic conditions, labor concerns, and beliefs about the nature of time are contained within predictive thought. The future of journalism has been asked when a number of possibilities are on the table and when fewer options are imaginable. Sometimes predictions are made when a journalist has a stake in seeing a particular vision enacted. There was no social stasis or treadmill for Munsey, who saw conglomeration as the key to good journalism, or for Stead, who imagined himself as the heroic journalist proselytizer. Both saw themselves as leaders of the free world. Feelings of euphoria and dysphoria, therefore, come and go and are not unique to one era. Nineteenth-century journalists like Stead and Maverick imagined their field’s future and the journalist’s future roles in society. Both were “feeling it,” riding high on the wave of mechanization.

Social roles are also embedded within occupational visions of the future. Will tomorrow’s journalists be tellers of truth, interpreters of data, shapers of public opinion, informers of policy makers, imaginers of social utopias? Some commentators insist that news must change to remain relevant in the digital age. In a world of abundant facts, reporters should be master interpreters, explaining the “what” and “how” to the public rather than reciting basic information (Cilizza 2016; Stephens 2014). As older models of journalism become outmoded, either by the Web or by computer programs, the hope is that professional journalists will find a niche explaining events. A similar impulse lies behind data-driven journalism, but in this case the journalists refashion themselves as computer workers, scraping the Web for reams of data, interpreting it, and presenting it to audiences in visually and narratively compelling ways. In solutions-based journalism, the reporter is a meta-social worker or public policy specialist, proposing potential solutions to local social problems based on what other locales have found successful.

There is also an emerging patronage system in which billionaires, foundations, and small donations prop up capital-intensive journalistic forms like investigative journalism. This is a good stopgap measure, and much of the work that has been supported by tech giants like Jeff Bezos, Pierre Omidyar, and others has typically been of high quality. But it begs the question: can journalists write exposés today about the very people and their tech companies who are sponsoring our journalism the way the Ida Tarbell wrote about Standard Oil?

The social roles future of news experts imagine might come to pass, but not always in the way they expect. Stead’s call for government by journalism, for instance, is certainly embodied in a figure like Breitbart’s Steve Bannon. Although Stead would disagree with his political vision and journalistic practices, Bannon is also “feeling it,” envisioning a future of infinite possibilities.

Occupational forecasting serves both psychological and pragmatic ends: it reduces anxieties at the same time that it identifies trends to guide present-day action. Because the future is speculative and can only be imagined or modeled, not recreated from memory, artifact, or written record, prediction-based advice runs a high risk of misdirection. We can safely assume that prognosticators will not determine the actual future of journalism. If Stead were really clairvoyant, the Titanic would have been spared and journalism saved. As Robert Heilbroner suggests, prediction is an exercise in futility. It is better to “ask whether it is imaginable… to exercise effective control over the future-shaping forces of Today” (1995, 95). It is only in this sense that discussions of the future and the social experiments they generate do, in fact, transform the field.

_____

Gretchen Soderlund is Associate Professor of Media History in the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism and Communication. She is the author of Sex Trafficking, Scandal, and the Transformation of Journalism, 1885-1917 (University of Chicago Press) and editor of Charting, Tracking, and Mapping: New Technologies, Labor, and Surveillance, a special issue of Social Semiotics. Her articles have appeared in such journals as American Quarterly, Feminist Formations, The Communication Review, Humanity, and Critical Studies in Media Communication.

_____

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Patrick Jones for his comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

_____

Notes

[1] The tremendous success of nineteenth-century self-made owner-editors like Benjamin Day or S.S. McClure can be attributed to innovations in content and funding models. In the 1830s, Day lowered the cost of his newspaper to only a penny, making it affordable to more New Yorkers, and made up for the decreased revenue by selling more advertising space. McClure did the same thing for magazines in the 1890s, selling his publication for a nickel instead of the standard quarter while increasing ad revenue. In doing so, both took advantage of untapped opportunities to reshape the news field in their respective eras.

[2] Before the 2016 election, this rhetoric united the libertarian left and the right. In a 2014 interview on Democracy Now that, not coincidentally, got positive play in the rightwing media, Glenn Greenwald lambasted Washington Post editors as, “old-style, old-media, pro-government journalists… the kind who have essentially made journalism in the U.S. neutered and impotent and obsolete” (Watson 2014).

[3] Villard also said of Munsey: “There is not a drop of the reformer’s blood in him; there is in him nothing that cries out in pain in response to the travails of multitudes” (1923, 72).

[4] The representational features of future thought are also culturally and historically specific (Rosenberg and Harding 2005).

[5] This more mobile, targeted approach to news production with fewer fixed duties or beats may offer a more varied work experience. But it has labor implications as well: it edges toward freelancing and it may be difficult to say no for reasons beyond beats. Further, reporters may find themselves over their heads in reporting on topics around which they can claim no expertise.

[6] Indeed, the FAA changed its policy on August 29, 2016 so that journalists do not need pilot’s licenses to fly drones, which will precipitate the increased use of the tool in the future (Etzler 2016).

_____

Works Cited

- Barthel, Michael. 2016. “Newspapers: Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center (Jun 15).

- Carr, David. 2014. “NYT’s David Carr on the Future of Journalism.” Youtube interview.

- Cilizza, Chris. 2016. “The Future of Journalism Is Saying ‘Yes.’ A Lot.” Washington Post (May 23).

- Crary, Jonathan. 2013. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

- Curran, James. 2010. “Technology Foretold.” In Natalie Fenton, ed., New Media, Old News: Journalism and Democracy in the Digital Age. London: Sage.

- Etzler, Allen. 2016. “Exploring the Use of Drones in Journalism.” News Media Alliance (Sep).

- Fabien, Johannes. 2002. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Friedhoff, Stefanie. 2015. “David Carr on Teaching and the Future of Journalism.” Boston Globe (Feb 13).

- Gottfried, Jeffrey and Eliza Shearer. 2016. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016.” Pew Research Center (May 26).

- Heilbroner, Robert. 1995. Visions of the Future: The Distant Past, Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kinsley, Michael. 2014. “The Front Page 2.0.” Vanity Fair (Apr 10).

- Lowrey, Wilson and Zhou Shan. 2016. “Journalism’s Fortune Tellers: Constructing the Future of News.” Journalism. 1-17.

- Maverick, Augustus. 1870. Henry J. Raymond and the New York Press for Thirty Years: Progress of American Journalism from 1840 to 1870. Hartford, CT: A.S. Hale and Company.

- McCaskill, Nolan. 2017. “Trump Backs Bannon: ‘The Media is the Opposition Party.’” Politico (Jan 27).

- Mellgard, Peter. 2015. “Medical 3 D Printing Will ‘Enable a New Kind of Future.” The World Post (Jun 22).

- Miller, Ross. 2015. “AP’s ‘Robot Journalists’ are Writing their own Stories Now.” The Verge (Jan 29).

- Munsey, Frank. 1903. “Journalism of the Future.” Munsey’s Magazine 28. 823-830.

- Neel, Patel V. 2015. “Dronalism is the Future of Journalism: The End of Privacy Cuts Both Ways.” Inverse (Sep).

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “Americans’ Internet Access: Percent of Adults 2000-2015.”

- Olson, Elizabeth. 2015. “Study Cites Lower Standards in Law School Admissions.” The New York Times (Oct. 26).

- Pistone, Michele and Michael Horn. 2016. Disrupting Law School: How Disruptive Innovation will Revolutionize the Legal World. Clayton Christenson Institute.

- Reinemann, Carsten and Philip Baugut. 2014. “German Political Journalism Between Change and Stability.” In Raymond Kuhn and Rasmus Kleis Nielson, eds., Political Journalism in Transition: Western Europe in a Comparative Perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reisch, Michael. 2013. “Social Work Education and the Neo-liberal Challenge: The U.S. Response to Increasing Global Inequality.” Social Work Education 32. 715-733.

- Rescher, Nicholas. 1998. Predicting the Future: An Introduction to the Theory of Forecasting. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Rogers, Tony. 2009. “A Timeline of Newspaper Closings and Calamities.” About.com.

- Rosa, Harmut. 2010. “Full Speed Burnout? From the Pleasures of the Motorcycle to the Bleakness of the Treadmill: The Dual Face of Social Acceleration.” International Journal of Motorcycle Studies 6:1.

- Rosa, Harmut. 2013. Social Acceleration – A New Theory of Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rosenberg, Daniel & Sandra Harding. 2005. In Daniel Rosenberg and Sandra Harding, eds., “Introduction: Histories of the Future.” Histories of the Future. Durham, NC:Duke University Press.

- Seamans, Robert & Feng Zhu. 2013. “Responses to Entry in Multi-Sided Markets: The Impact of Craigslist on Local Newspapers.” Management Science 60. 476-493.

- Sharma, Sarah. 2014. In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Schwartz, Vanessa. 1999. Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siécle Paris. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Solomon, Steven Davidoff. 2015. “Law Schools and Industry Show Signs of Life Despite Forecasts of Doom.” The New York Times (Mar 31).

- Stead, William. 1887. “The Future of Journalism.” Contemporary Review 50. 664-679.

- Stead, William. 1893. “From Old World to New: or, A Christmas Story of the Chicago Exhibition.” Review of Reviews.

- Stephens, Mitchell. 2014. Beyond News: The Future of Journalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Villard, Oswald Garrison. 1923. Some Newspapers and Newspaper-Men. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Watson, Steve. 2014. “Greenwald Slams ‘Neutered And Impotent and Obsolete Media.’” Infowars.

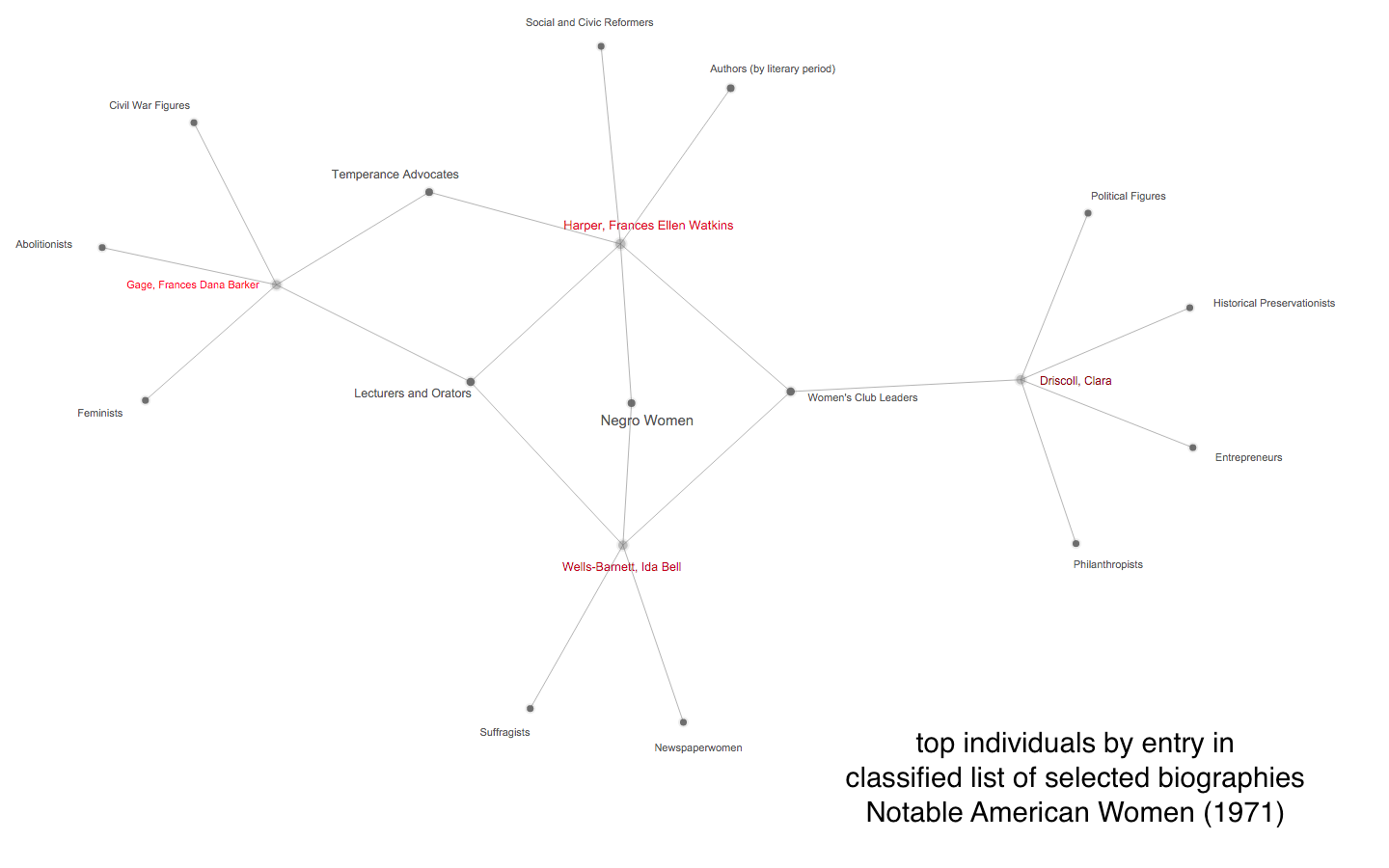

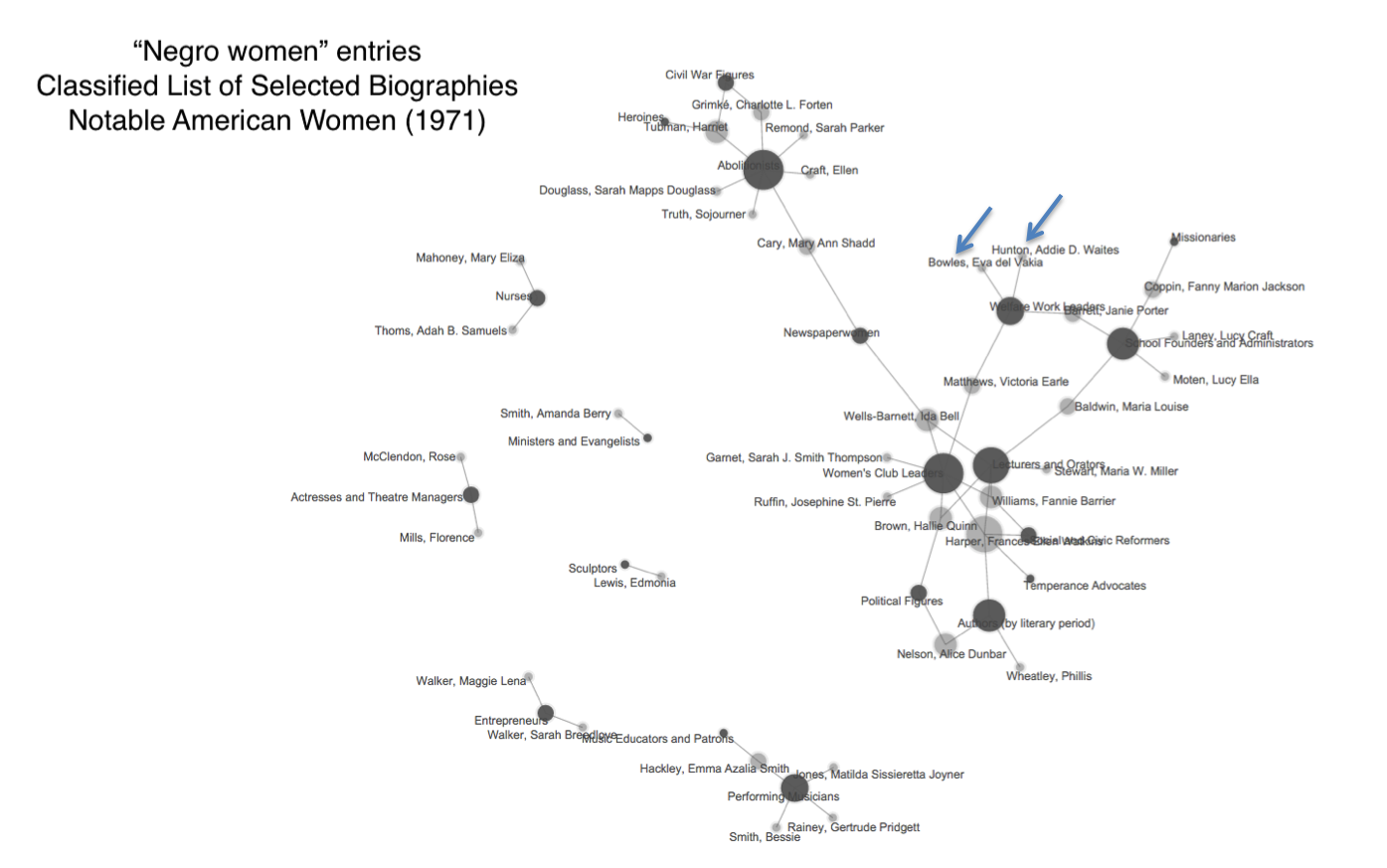

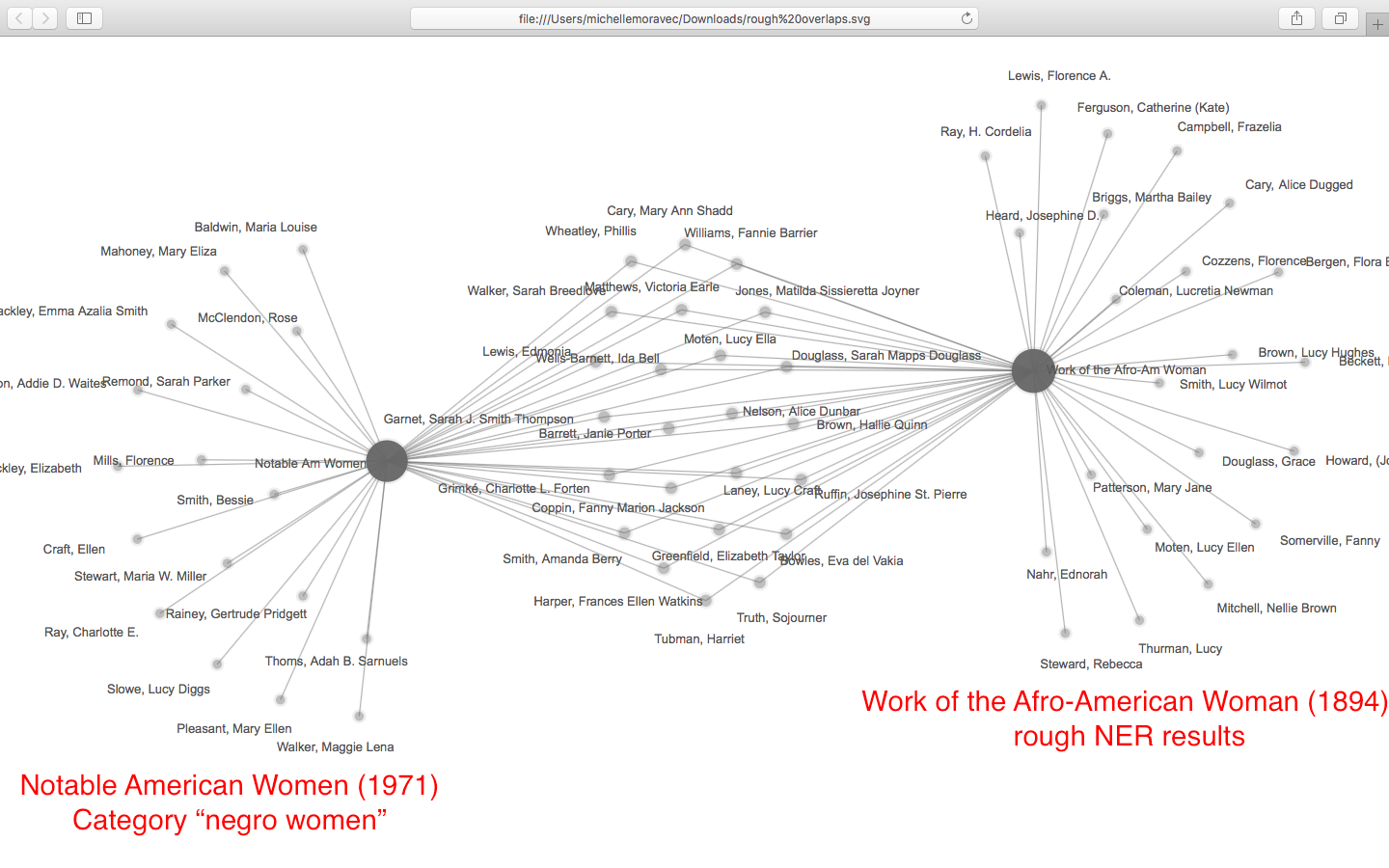

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed

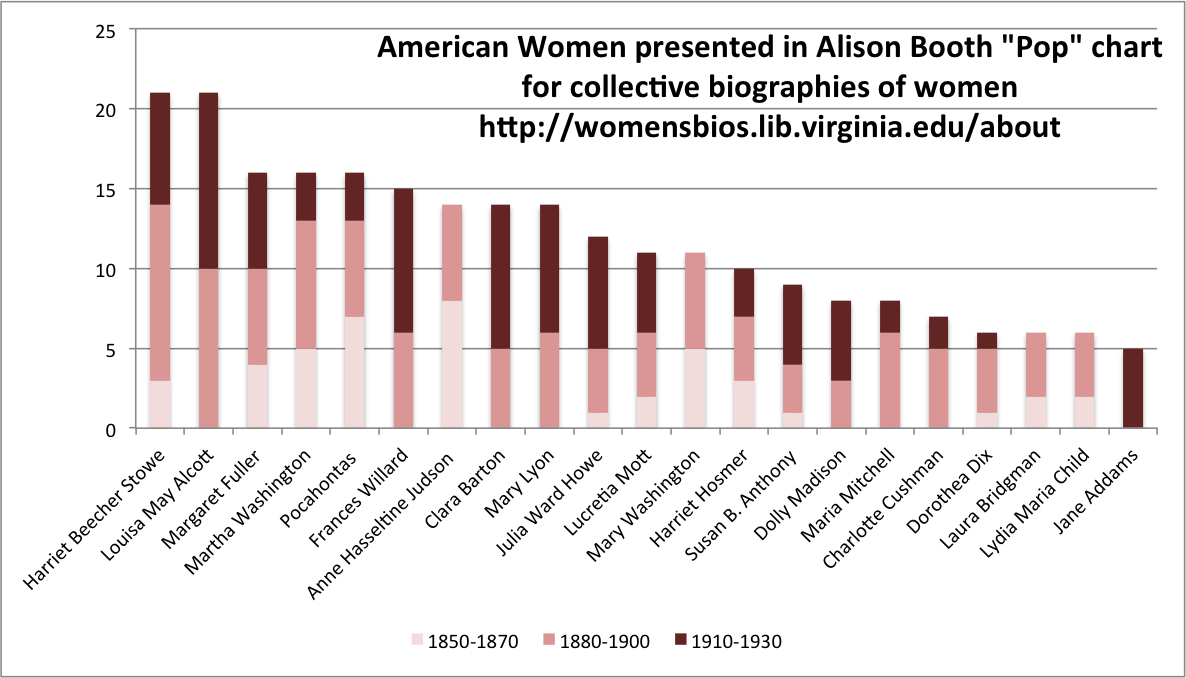

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed  mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)

a review of Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015) and The Anthrobscene (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)