(This catalog essay was written in 2011 for the exhibition “Chaos as Usual,” curated by Hanne Mugaas at the Bergen Kunsthall in Norway. Artists in the exhibition included Philip Kwame Apagya, Ann Craven, Liz Deschenes, Thomas Julier [in collaboration with Cédric Eisenring and Kaspar Mueller], Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied, Takeshi Murata, Seth Price, and Antek Walczak.)

There is something about the digital. Most people aren’t quite sure what it is. Or what they feel about it. But something.

In 2001 Lev Manovich said it was a language. For Steven Shaviro, the issue is being connected. Others talk about “cyber” this and “cyber” that. Is the Internet about the search (John Battelle)? Or is it rather, even more primordially, about the information (James Gleick)? Whatever it is, something is afoot.

What is this something? Given the times in which we live, it is ironic that this term is so rarely defined and even more rarely defined correctly. But the definition is simple: the digital means the one divides into two.

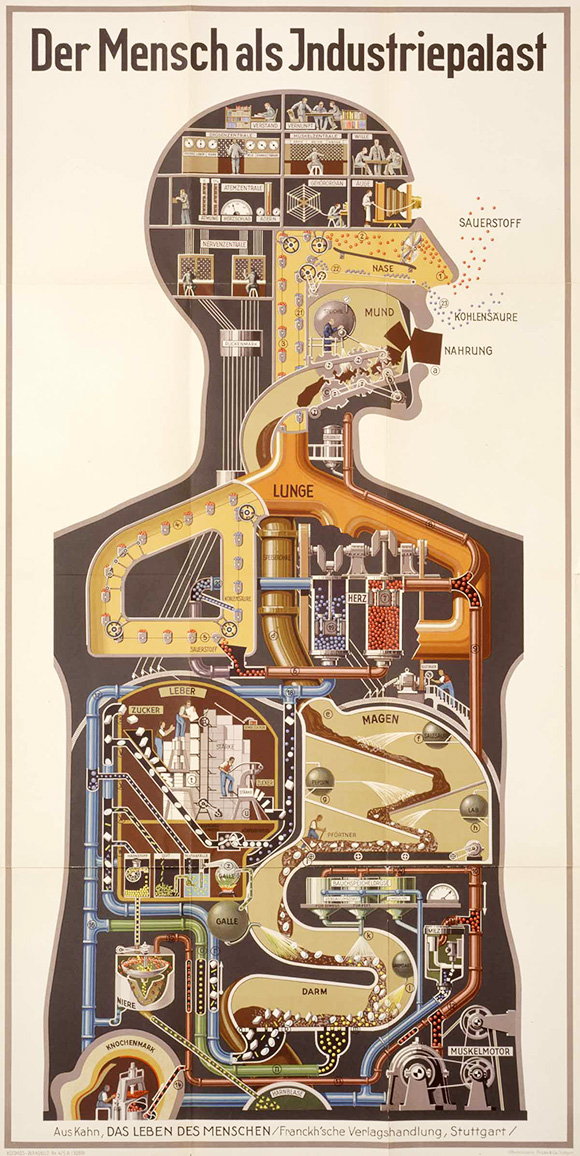

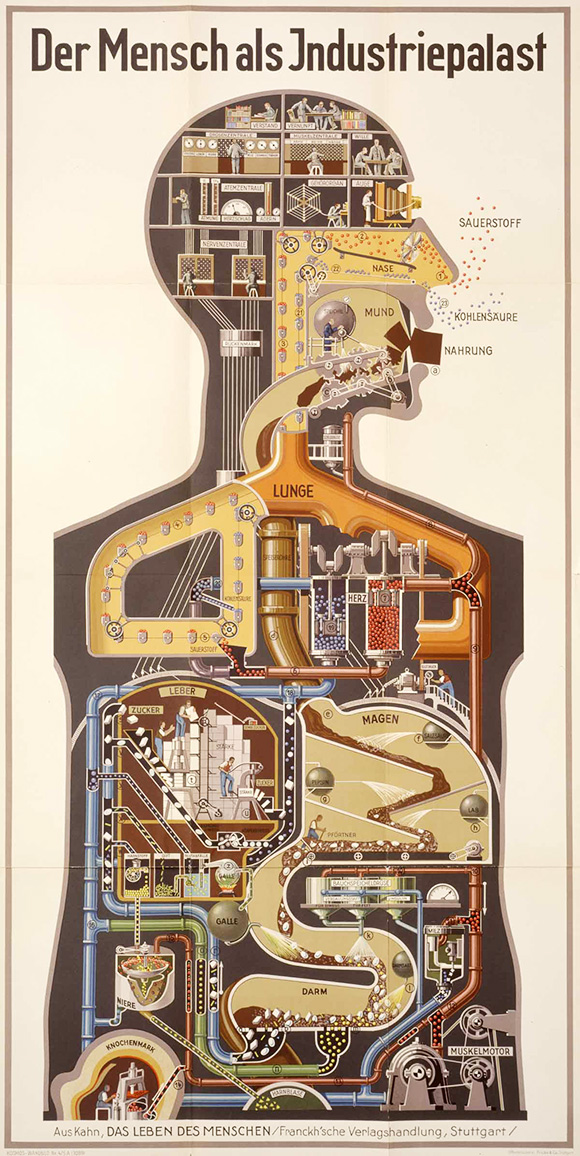

Digital doesn’t mean machine. It doesn’t mean virtual reality. It doesn’t even mean the computer – there are analog computers after all, like grandfather clocks or slide rules. Digital means the digits: the fingers and toes. And since most of us have a discrete number of fingers and toes, the digital has come to mean, by extension, any mode of representation rooted in individually separate and distinct units. So the natural numbers (1, 2, 3, …) are aptly labeled “digital” because they are separate and distinct, but the arc of a bird in flight is not because it is smooth and continuous. A reel of celluloid film is correctly called “digital” because it contains distinct breaks between each frame, but the photographic frames themselves are not because they record continuously variable chromatic intensities.

We must stop believing the myth, then, about the digital future versus the analog past. For the digital died its first death in the continuous calculus of Newton and Leibniz, and the curvilinear revolution of the Baroque that came with it. And the digital has suffered a thousand blows since, from the swirling vortexes of nineteenth-century thermodynamics, to the chaos theory of recent decades. The switch from analog computing to digital computing in the middle twentieth century is but a single battle in the multi-millennial skirmish within western culture between the unary and the binary, proportion and distinction, curves and jumps, integration and division – in short, over when and how the one divides into two.

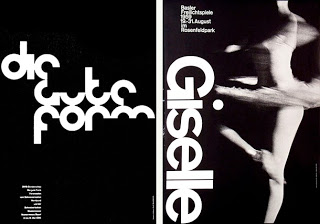

What would it mean to say that a work of art divides into two? Or to put it another way, what would art look like if it began to meditate on the one dividing into two? I think this is the only way we can truly begin to think about “digital art.” And because of this we shall leave Photoshop, and iMovie, and the Internet and all the digital tools behind us, because interrogating them will not nearly begin to address these questions. Instead look to Ann Craven’s paintings. Or look to the delightful conversation sparked here between Philip Kwame Apagya and Liz Deschenes. Or look to the work of Thomas Julier, even to a piece of his not included in the show, “Architecture Reflecting in Architecture” (2010, made with Cedric Eisenring), which depicts a rectilinear cityscape reflected inside the mirror skins of skyscrapers, just like Saul Bass’s famous title sequence in North By Northwest (1959).

All of these works deal with the question of twoness. But it is twoness only in a very particular sense. This is not the twoness of the doppelganger of the romantic period, or the twoness of the “split mind” of the schizophrenic, and neither is it the twoness of the self/other distinction that so forcefully animated culture and philosophy during the twentieth century, particularly in cultural anthropology and then later in poststructuralism. Rather we see here a twoness of the material, a digitization at the level of the aesthetic regime itself.

Consider the call and response heard across the works featured here by Apagya and Deschenes. At the most superficial level, one might observe that these are works about superimposition, about compositing. Apagya’s photographs exploit one of the oldest and most useful tricks of picture making: superimpose one layer on top of another layer in order to produce a picture. Painters do this all the time of course, and very early on it became a mainstay of photographic technique (even if it often remained relegated to mere “trick” photography), evident in photomontage, spirit photography, and even the side-by-side compositing techniques of the carte de visite popularized by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri in the 1850s. Recall too that the cinema has made productive use of superimposition, adopting the technique with great facility from the theater and its painted scrims and moving backdrops. (Perhaps the best illustration of this comes at the end of A Night at the Opera [1935], when Harpo Marx goes on a lunatic rampage through the flyloft during the opera’s performance, raising and lowering painted backdrops to great comic effect.) So the more “modern” cinematic techniques of, first, rear screen projection, and then later chromakey (known commonly as the “green screen” or “blue screen” effect), are but a reiteration of the much longer legacy of compositing in image making.

Deschenes’ “Green Screen #4” points to this broad aesthetic history, as it empties out the content of the image, forcing us to acknowledge the suppressed color itself – in this case green, but any color will work. Hence Deschenes gives us nothing but a pure background, a pure something.

Allowed to curve gracefully off the wall onto the floor, the green color field resembles the “sweep wall” used commonly in portraiture or fashion photography whenever an artist wishes to erase the lines and shadows of the studio environment. “Green Screen #4” is thus the antithesis of what has remained for many years the signal art work about video chromakey, Peter Campus’ “Three Transitions” (1973). Whereas Campus attempted to draw attention to the visual and spatial paradoxes made possible by chromakey, and even in so doing was forced to hide the effect inside the jittery gaps between images, Deschenes by contrast feels no such anxiety, presenting us with the medium itself, minus any “content” necessary to fuel it, minus the powerful mise en abyme of the Campus video, and so too minus Campus’ mirthless autobiographical staging. If Campus ultimately resolves the relationship between images through a version of montage, Deschenes offers something more like a “divorced digitality” in which no two images are brought into relation at all, only the minimal substrate remains, without input or output.

The sweep wall is evident too in Apagya’s images, only of a different sort, as the artifice of the various backgrounds – in a nod not so much to fantasy as to kitsch – both fuses with and separates from the foreground subject. Yet what might ultimately unite the works by Apagya and Deschenes is not so much the compositing technique, but a more general reference, albeit oblique but nevertheless crucial, to the fact that such techniques are today entirely quotidian, entirely usual. These are everyday folk techniques through and through. One needs only a web cam and simple software to perform chromakey compositing on a computer, just as one might go to the county fair and have one’s portrait superimposed on the body of a cartoon character.

What I’m trying to stress here is that there is nothing particularly “technological” about digitality. All that is required is a division from one to two – and by extension from two to three and beyond to the multiple. This is why I see layering as so important, for it spotlights an internal separation within the image. Apagya’s settings are digital, therefore, simply by virtue of the fact that he addresses our eye toward two incompatible aesthetic zones existing within the image. The artifice of a painted backdrop, and the pose of a person in a portrait.

Certainly the digital computer is “digital” by virtue of being binary, which is to say by virtue of encoding and processing numbers at the lowest levels using base-two mathematics. But that is only the most prosaic and obvious exhibit of its digitality. For the computer is “digital” too in its atomization of the universe, into, for example, a million Facebook profiles, all equally separate and discrete. Or likewise “digital” too in the computer interface itself which splits things irretrievably into cursor and content, window and file, or even, as we see commonly in video games, into heads-up-display and playable world. The one divides into two.

So when clusters of repetition appear across Ann Craven’s paintings, or the iterative layers of the “copy” of the “reconstruction” in the video here by Thomas Julier and Cédric Eisenring, or the accumulations of images that proliferate in Olia Lialina and Dragon Espenschied’s “Comparative History of Classic Animated GIFs and Glitter Graphics” [2007] (a small snapshot of what they have assembled in their spectacular book from 2009 titled Digital Folklore), or elsewhere in works like Oliver Laric’s clipart videos (“787 Cliparts” [2006] and “2000 Cliparts” [2010]), we should not simply recall the famous meditations on copies and repetitions, from Walter Benjamin in 1936 to Gilles Deleuze in 1968, but also a larger backdrop that evokes the very cleavages emanating from western metaphysics itself from Plato onward. For this same metaphysics of division is always already a digital metaphysics as it forever differentiates between subject and object, Being and being, essence and instance, or original and repetition. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that we see here such vivid aesthetic meditations on that same cleavage, whether or not a computer was involved.

Another perspective on the same question would be to think about appropriation. There is a common way of talking about Internet art that goes roughly as follows: the beginning of net art in the middle to late 1990s was mostly “modernist” in that it tended to reflect back on the possibilities of the new medium, building an aesthetic from the material affordances of code, screen, browser, and jpeg, just as modernists in painting or literature built their own aesthetic style from a reflection on the specific affordances of line, color, tone, or timbre; whereas the second phase of net art, coinciding with “Web 2.0” technologies like blogging and video sharing sites, is altogether more “postmodern” in that it tends to co-opt existing material into recombinant appropriations and remixes. If something like the “WebStalker” web browser or the Jodi.org homepage are emblematic of the first period, then John Michael Boling’s “Guitar Solo Threeway,” Brody Condon’s “Without Sun,” or the Nasty Nets web surfing club, now sadly defunct, are emblematic of the second period.

I’m not entirely unsatisfied by such a periodization, even if it tends to confuse as many things as it clarifies – not entirely unsatisfied because it indicates that appropriation too is a technique of digitality. As Martin Heidegger signals, by way of his notoriously enigmatic concept Ereignis, western thought and culture was always a process in which a proper relationship of belonging is established in a world, and so too appropriation establishes new relationships of belonging between objects and their contexts, between artists and materials, and between viewers and works of art. (Such is the definition of appropriation after all: to establish a belonging.) This is what I mean when I say that appropriation is a technique of digitality: it calls out a distinction in the object from “where it was prior” to “where it is now,” simply by removing that object from one context of belonging and separating it out into another. That these two contexts are merely different – that something has changed – is evidence enough of the digitality of appropriation. Even when the act of appropriation does not reduplicate the object or rely on multiple sources, as with the artistic ready-made, it still inaugurates a “twoness” in the appropriated object, an asterisk appended to the art work denoting that something is different.

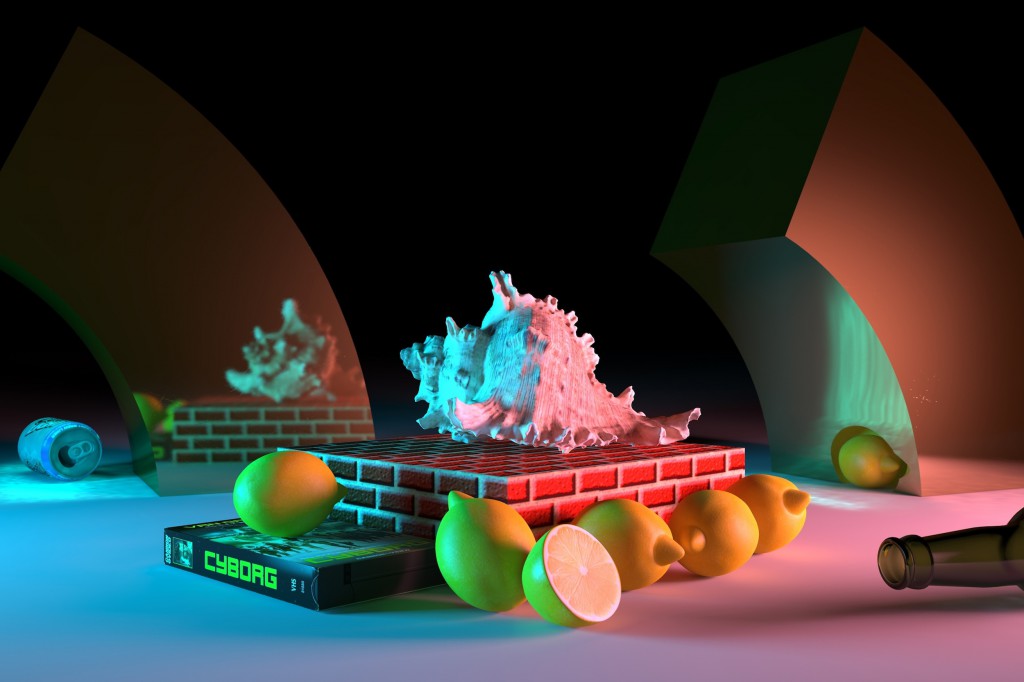

Perhaps this is why Takeshi Murata continues his exploration of the multiplicities at the core of digital aesthetics by returning to that age old format, the still life. Is not the still life itself a kind of appropriation, in that it brings together various objects into a relationship of belonging: fig and fowl in the Dutch masters, or here the various detritus of contemporary cyber culture, from cult films to iPhones?

Because appropriation brings things together it must grapple with a fundamental question. Whatever is brought together must form a relation. These various things must sit side-by-side with each other. Hence one might speak of any grouping of objects in terms of their “parallel” nature, that is to say, in terms of the way in which they maintain their multiple identities in parallel.

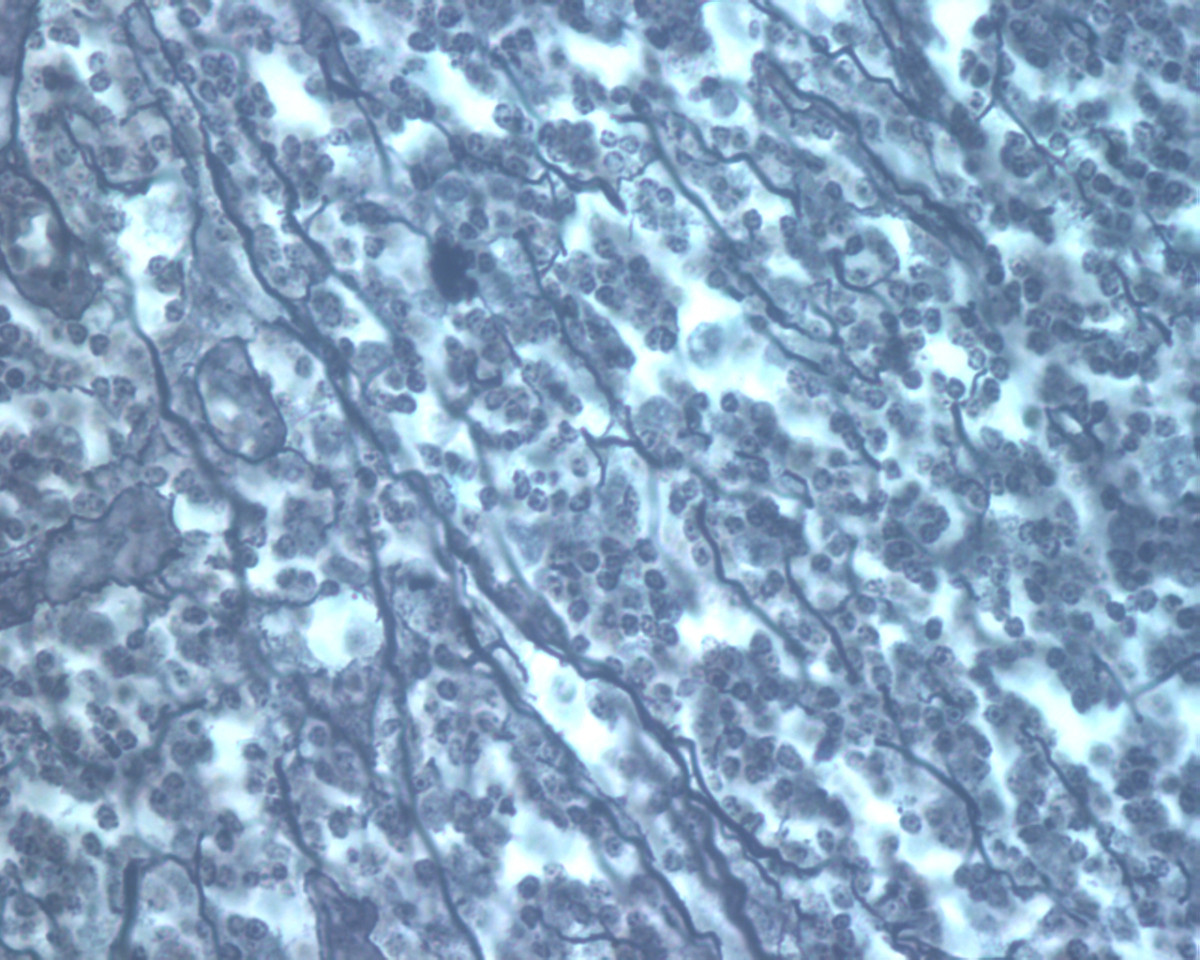

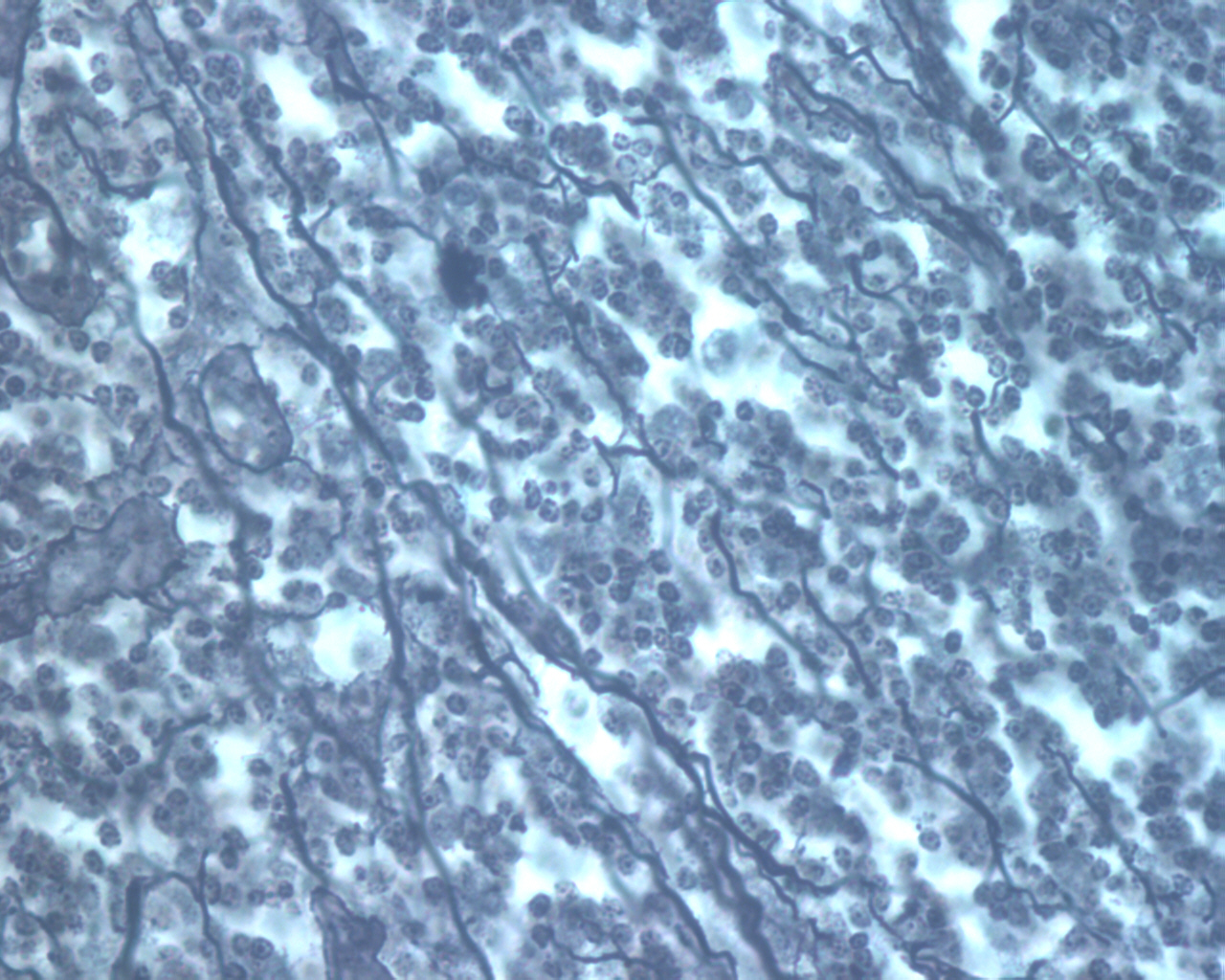

But let us dwell for a moment longer on these agglomerations of things, and in particular their “parallel” composition. By parallel I mean the way in which digital media tend to segregate and divide art into multiple, separate channels. These parallel channels may be quite manifest, as in the separate video feeds that make up the aforementioned “Guitar Solo Threeway,” or they may issue from the lowest levels of the medium, as when video compression codecs divide the moving image into small blocks of pixels that move and morph semi-autonomously within the frame. In fact I have found it useful to speak of this in terms of the “parallel image” in order to differentiate today’s media making from that of a century ago, which Friedrich Kittler and others have chosen to label “serial” after the serial sequences of the film strip, or the rat-ta-tat-tat of a typewriter.

Thus films like Tatjana Marusic’s “The Memory of a Landscape” (2004) or Takeshi Murata’s “Monster Movie” (2005) are genuinely digital films, for they show parallelity in inscription. Each individual block in the video compression scheme has its own autonomy and is able to write to the screen in parallel with all the other blocks. These are quite literally, then, “multichannel” videos – we might even take a cue from online gaming circles and label them “massively multichannel” videos. They are multichannel not because they require multiple monitors, but because each individual block or “channel” within the image acts as an individual micro video feed. Each color block is its own channel. Thus, the video compression scheme illustrates, through metonymy, how pixel images work in general, and, as I suggest, it also illustrates the larger currents of digitality, for it shows that these images, in order to create “an” image must first proliferate the division of sub-images, which themselves ultimately coalesce into something resembling a whole. In other words, in order to create a “one” they must first bifurcate the single image source into two or more separate images.

The digital image is thus a cellular and discrete image, consisting of separate channels multiplexed in tandem or triplicate or, greater, into nine, twelve, twenty-four, one hundred, or indeed into a massively parallel image of a virtually infinite visuality.

For me this generates a more appealing explanation for why art and culture has, over the last several decades, developed a growing anxiety over copies, repetitions, simulations, appropriations, reenactments – you name it. It is common to attribute such anxiety to a generalized disenchantment permeating modern life: our culture has lost its aura and can no longer discern an original from a copy due to endless proliferations of simulation. Such an assessment is only partially correct. I say only partially because I am skeptical of the romantic nostalgia that often fuels such pronouncements. For who can demonstrate with certainty that the past carried with it a greater sense of aesthetic integrity, a greater unity in art? Yet the assessment begins to adopt a modicum of sense if we consider it from a different point of view, from the perspective of a generalized digitality. For if we define the digital as “the one dividing into two,” then it would be fitting to witness works of art that proliferate these same dualities and multiplicities. In other words, even if there was a “pure” aesthetic origin it was a digital origin to begin with. And thus one needn’t fret over it having infected our so-called contemporary sensibilities.

Instead it is important not to be blinded by the technology. But rather to determine that, within a generalized digitality, there must be some kind of differential at play. There must be something different, and without such a differential it is impossible to say that something is something (rather than something else, or indeed rather than nothing). The one must divide into something else. Nothing less and nothing more is required, only a generic difference. And this is our first insight into the “something” of the digital.

_____

Alexander R. Galloway is a writer and computer programer working on issues in philosophy, technology, and theories of mediation. Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, he is author of several books and dozens of articles on digital media and critical theory, including Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization (MIT, 2006), Gaming: Essays in Algorithmic Culture (University of Minnesota, 2006); The Interface Effect (Polity, 2012), and most recently Laruelle: Against the Digital (University of Minnesota, 2014), reviewed here in 2014. Galloway has recently been writing brief notes on media and digital culture and theory at his blog, on which this post first appeared.