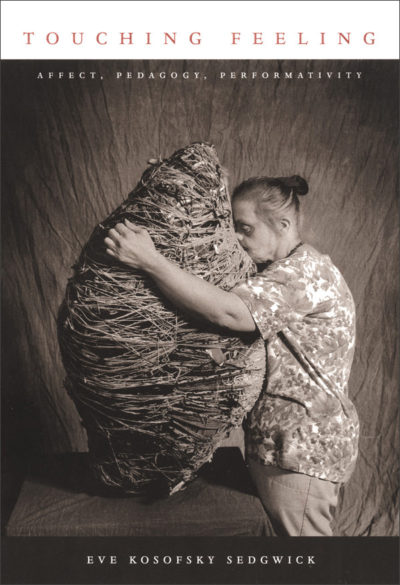

The late queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick is known for her tenacious commitment to the indeterminate possibilities that nondualism might offer sustained inquiries into minor aesthetics, politics, and performance. In the introduction to Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Sedgwick turns to touch and texture as particularly generative heuristic sites for opening the book’s avowed project, namely the exploration of “promising tools and techniques for nondualist thought and pedagogy.”[1] Moving through psychoanalysis, queer theory, and sexuality studies, the text probes entanglements of intimacy and emotion, desire and eroticism, that animate experience and draw social life into the myriad folds of material and nonlinguistic relations. As Lauren Berlant asserts of Sedgwick’s text, “the performativity of knowledge beyond speech – aesthetic, bodily, affective – is its real topic.”[2]

One of Sedgwick’s most important and enduring legacies is a radically queer heuristic that endeavors to make theorizable the imperceptible and obscure relationships between affect, pedagogy, and performativity, without reproducing the limits and burdens of epistemology (even antiessentialist epistemology), with its “demand on essential truth.”[3] For Sedgwick, texture and touch offer potential instances of sidestepping or evading the foreclosures of structure and its attendant calcification of subject-object relations, a pivot towards antinormative pedagogies of reading and interpretation. Following Henry James, Sedgwick suggests that “to perceive texture is always, immediately, and de facto to be immersed in a field of active narrative hypothesizing, testing, and re-understanding of how physical properties act and are acted upon over time,” to become engaged in a series of speculative departures rather than analytical arrivals.[4] Similarly, Sedgwick finds in the sense of touch a perceptual experience that “makes nonsense out of any dualistic understanding of agency and passivity.”[5] Particularly relevant for our purposes is Sedgwick’s turn to the registers of difference between texture and texxture as a guide for thinking about forms of desire, perception, and interpretation that exceed normative modalities of belonging in, being with, and making sense of the world.

Teasing out the implications of Renu Bora’s taxonomy of textural difference, Sedgwick tells us that

Bora notes that ‘smoothness is both a type of texture and texture’s other.’ His essay makes a very useful distinction between two kinds, or senses, of texture, which he labels ‘texture’ with one x and ‘texxture’ with two x’s. Texxture is the kind of texture that is dense with offered information about how, substantively, historically, materially, it came into being. A brick or metal-work pot that still bears the scars and uneven sheen of its making would exemplify texxture in this sense. But there is also the texture – one x this time – that defiantly or even invisibly blocks or refuses such information; there is texture usually glossy if not positively tacky, that insists instead on the polarity between substance and surface, texture that signifies the willed erasure of its history.[6]

Though one might be tempted to singularly assign to texture’s “manufactured or overhighlighted surface” the properties and pitfalls of “psychoanalytic and commodity fetishism,” in fact,

the narrative-performative density of the other kind of texxture – its ineffaceable historicity – also becomes susceptible to a kind of fetish-value. An example of the latter might occur where the question is one of exotism, of the palpable and highly acquirable textural record of the cheap, precious work of many foreign hands in the light of many damaged foreign eyes. [7]

Paradoxically, it is precisely the failure of texture to erase the internal historicity that would appear to be self-evidently registered on the surface of texxture, which allows Sedgwick to effectively grant the former an elusive depth, declaring that, “however high the gloss, there is no such thing as textural lack.”[8] Meanwhile, texxture’s presumably inescapable depth seems to recede across the surficial “scars and uneven sheen” that are read as the signatures of its making. For Sedgwick, one of the primary implications of these phenomenological variegations and perplexities is that texture, “in short, comprises an array of perceptual data that includes repetition, but whose degree of organization hovers just below the level of shape or structure…[the] not-yet-differentiated quick from which the performative emerges.”[9] In this way,

texture seems like a promising level of attention for shifting the emphasis of some interdisciplinary conversations away from the recent fixation on epistemology…by asking new questions about phenomenology and affect, [for what]…texture and affect, touching and feeling…have in common is that…both are irreducibly phenomenological.[10]

On the one hand, Sedgwick’s turn to texture divulges extra-linguistic affiliations that performatively surprise, facilitating an erotic retrieval of subjective and aesthetic non-mastery that continues to resonate with ongoing critiques of the aesthetic. And yet, while Sedgwick’s assertions about affectivity and touch facilitate an opening for a theoretical re-evaluation of notions of agency, passivity, and self-perception, they are also deeply problematic. For what does phenomenology, which takes the body as our “point of view in the world,”[11] have to say to those who, following Frantz Fanon, have never had a body, but rather its theft, those who have only ever been granted the dissimulation of a body, “sprawled out, distorted, recolored, clad in mourning[?]”[12] What of those whose skin is constantly resurfaced as depthless texxture, a texxture whose surficial inscriptions are read as proxies for the historicity that the over-glossed surface would seek to expunge? In other words, Sedgwick’s ruminations disclose an undeclared, but nevertheless central, conceit that has significant implications for thinking about the bearing of form on ontology: namely that, for Sedgwick, the texturized valences of touch are implicated in, rather than a violent displacement from, the symbolic economy of the human.

In theorizing touch, might we trouble the presumption that aesthetics, subjectivity, and desire – or more precisely their entwinement – are necessarily embedded within the normative regime of the human? I am interested, in other words, in how Sedgwick’s observations on touch might occasion, even as they displace, a different set of interrelated questions regarding ontological mattering and the fashioning of aesthetic subjectivity. Calvin Warren’s assertion that “[q]ueer theory’s ‘closeted humanism’ reconstitutes the ‘human’ even as it attempts to challenge and, at times, erase it,” demands we reconsider any theory (about the queerness) of touch that has yet to grapple with its universalist underpinnings. It would seem that queer theory, even one as vigorously attuned to the textured rediscovery of minor forms as Sedgwick’s, nevertheless conceives desire, sexuality, and gender as co-extensive with the erotic architecture of the (queerly differentiated/differentiating) human subject. Suffering may be aestheticized, but it is not reckoned with as an ontological imposition – as a “grammar,” to use Frank B. Wilderson’s language[13] – out of which an aesthesis necessarily emerges.

Insofar as texxture bears the inscription of its material conditions of possibility, it should direct us toward a genealogy of substance at odds with surface appearance. At stake is what film scholar Laura Marks theorizes under the rubric of the haptic[14] – the tactile, kinesthetic, and proprioceptive dimensions of touch, the irreducibly haptic valences of touch that pressure prevailing distinctions between substance and surface, inside and outside, body and flesh. A question at once animated and omitted by queer theory’s inquiries into touch: how to theorize texxture with regard to a history of bodily wounding occasioned by touch, when it is texxture that is seized upon by the various proxies for touch that willingly or inadvertently redouble racial fantasies of violation? Thinking the haptic irreducibility of the aesthetic requires constant re-attunement to the violence touch occasions and to the violations which occasion touch. If touch is ultimately inextricable from the aesthetic economy of worldly humanity, then, apropos Saidiya Hartman, we are compelled to think about the violence that resides in our habits of worlding.[15]

Without even addressing the massive implications that attend the frequent conflation of being with body, what cleaves to being within the context of critical theory’s alternately residual or unapologetic phenomenology, is a corporeal subject whose situatedness within and for the world is not only predetermined, but whose predetermination is taken for granted as the condition of possibility for sentient touch. Such unwitting Calvinism, which would seem to take Merleau-Ponty at his word when he declares that “every relation with being is simultaneously a taking and being taken,”[16] inevitably reproduces and rubs up against a foundational schism: being taken, where the traces of an inflective doubling disclose a morphological distinction at the level of species-being.[17] Just as the tectonics of touch – their quakes and strains, fractures and fault lines, accretions and exfoliations – can hardly be taken for simply surface phenomena, neither can they be assumed to unfold upon a universal plane of experience, or to obtain between essentially analogous subjects within a common field of relation (a fact betrayed by the nominative excess which threatens to spill from the very word, “field”). Touch cannot be understood apart from the irreducibly racial valences and demarcations of corporeality in the wake of transatlantic slavery.

In her landmark essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Hortense Spillers theorizes one of the central cleavages of the modern world, wrought and sundered in the cataclysmic passages of racial slavery: that of body and flesh, which Spillers takes as the foremost distinction “between captive and liberated subjects-positions”:

before the “body” there is the “flesh,” that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse or the reflexes of iconography. Even though the European hegemonies stole bodies – some of them female – out of West African communities in concert with the African “middleman,” we regard this human and social irreparability as high crimes against the flesh, as the person of African females and males registered the wounding. If we think of the “flesh” as a primary narrative, then we mean its seared, divided, ripped-apartness, riveted to the ship’s hole, fallen, or “escaped” overboard.[18]

Flesh is before the body in a dual sense. On the one hand, as Alexander Weheliye stresses, flesh is “a temporal and conceptual antecedent to the body[.]”[19] The body, which may be taken to stand for “legal personhood qua self-possession,”[20] is violently produced through the “high crimes against the flesh.” On the other hand, flesh is before the body in that it is everywhere subject to and at the disposal of the body. The body is cleaved from flesh, while flesh is serially cleaved by the body. As Fred Moten suggests, the body only emerges through the disciplining of flesh.[21]

This diametric arrangement of corporeal exaltation and abjection is registered, as Spillers emphasizes, in “the tortures and instruments of captivity,” those innumerable, unspeakable brutalities by which flesh is irrevocably marked:

The anatomical specifications of rupture, of altered human tissue, take on the objective description of laboratory prose – eyes beaten out, arms, backs, skulls branded, a left jaw, a right ankle, punctured; teeth missing, as the calculated work of iron, whips, chains, knives, the canine patrol; the bullet.[22]

The unspeakability of such woundings, however, is not merely a function of their terror and depravity, but rather a consequence of the ways flesh has been made to bear the conditions of im/possibility of and for a semiotics which takes itself to be the very foundation of language, at least in its modern dissimulations.[23] In Moten’s illumination, “[t]he value of the sign, its necessary relation to the possibility of (a universal science of and a universal) language, is only given in the absence or supercession of, or the abstraction from, sounded speech— its essential materiality is rendered ancillary by the crossing of an immaterial border or by a differentializing inscription.”[24] Thus, when Spillers writes that “[t]hese undecipherable markings on the captive body render a kind of hieroglyphics of the flesh whose severe disjunctures come to be hidden to the cultural by seeing skin color[,]”[25] we may surmise that what Frantz Fanon termed “epidermalization” – the process by which a “historico-racial schema” is violently imposed upon the skin, that which, for the Black, forecloses the very possibility of assuming a body (to borrow Gayle Salamon’s turn of phrase) – is, among other things, a mechanism of semiotic concealment.[26] (R.A. Judy refers to it as “something like [flesh]…being parenthesized.”)[27] What is hidden and rehidden, the open secret alternately buried within and exposed upon the skin, is not merely a system of corporeal apartheid, but moreover what Spillers identifies as the vestibularity of flesh to culture. “This body whose flesh carries the female and the male to the frontiers of survival bears in person the marks of a cultural text whose inside has been turned outside.”[28]

Speaking at a conference day I curated for the Stedelijk Museum of Art and Studium Generale Rietveld Academy in 2018, entitled “There’s a Tear in the World: Touch After Finitude,” Spillers revisited her classic essay, drawing out its implications for thinking through questions of touch and hapticality.[29] For Spillers, touch “might be understood as the gateway to the most intimate experience and exchange of mutuality between subjects, or taken as the fundamental element of the absence of self-ownership…it defines at once, in the latter instance, the most terrifying personal and ontological feature of slavery’s regimes across the long ages.”[30] To meaningfully reckon with “the contradictory valences of the haptic” is to “attempt an entry into this formidable paradox, which unfolds a troubled intersubjective legacy – and, perhaps, troubled to the extent that one of these valences of touch is not walled off from the other, but haunts it, shadows it, as its own twin possibility.”[31] Spillers follows with an unavoidable question: “did slavery across the Americas rupture ties of kinship and filiation so completely that the eighteenth century demolishes what Constance Classen, in The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch, calls a ‘tactile cosmology’?” If so, then the dimensions of touch which are understood as “curative, healing, erotic, [or] restorative” cannot be held apart from the myriad “violation[s] of the boundaries of the ego in the enslaved, that were not yet accorded egoistic status, or, in brief, subjecthood, subjectivity.”[32]

Touch, then, evokes the vicious, desperate attempts of the white, the settler, to feign the ontic verity, stability, and immutability of an irreducibly racial subject-object (non-)relation through what Frank Wilderson would call “gratuitous violence”[33] as much as it does the corporeal life of intra- and intersubjective relationality and encounter. If even critical discourse on these latter, corporeal happenings tends to assume the facticity of the juridically sanctioned pretense to self-possession Spillers calls “bodiedness,” then “flesh describes an alien entity,” a corporeal formation fundamentally unable to “ward off another’s touch…[who] may be invaded or entered or penetrated, so to speak, by coercive power” in any given place or moment. It is, in other words, precisely “the captive body’s susceptibility to being touched [which] places this body on the side of the flesh,”[34] a susceptibility which is not principally historical, but ontological, even as flesh constitutes, to borrow Moten’s phrasing, “a general and generative resistance to what ontology can think[.]”[35] Spillers brings us to the very threshold of feeling, where to be cast on the side of the flesh is to inhabit the cut between existence and ontology. Black life is being-touched.

How might we bring such knowledge to bear upon our understanding of different aesthetic practices, forms, and traditions? What if Theodor Adorno’s conception of the “shudder” experienced by the subject in his ephemeral encounter with a “genuine relation to art,” that “involuntary comportment” which is “a memento of the liquidation of the I,”[36] must be understood as the corporeal expression of a subject whose conditions of existence sustain the fantasy of being-untouched? How might such an interpretation serve not simply to foreground an indictment, but also aspire to linger with the political, ethical, and analytic questions that emerge from the entanglements of hapticality, aesthetics, and violence, questions which are unavoidable for those given to blackness? “The hold’s terrible gift,” Moten and Harney maintain, “was to gather dispossessed feelings in common, to create a new feel in the undercommons.”[37] And, as Moten has subsequently reminded us, violence cannot be excised from the materiality of this terrible gift, which is none other than black art:

Black art neither sutures nor is sutured to trauma. There’s no remembering, no healing. There is, rather, a perpetual cutting, a constancy of expansive and enfolding rupture and wound, a rewind that tends to exhaust the metaphysics upon which the idea of redress is grounded.[38]

Black art promises neither redemption nor emancipation. The “transcendent power” that Peter de Bolla, for example, finds gloriously manifest by an artwork such as Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà, that encounter with a “timeless…elemental beauty” which constitutes “one of the basic building blocks of our shared culture, our common humanity,”[39] is a fabrication of a structure of aesthetic experience that is wholly unavailable to the black, who, after all, has never been human. If Immanuel Kant, as the preeminent architect of modern European aesthetic philosophy, understood art to emerge precisely in its separation from nature, as “a work of man,”[40]then it is clear his transcendental aesthetic is not the province of black art. For, as Denise Ferreira da Silva argues, modernity’s “arsenal of raciality” places the black before the “scene of nature,” as “as affectable things…subjected to the determination of both the ‘laws of nature’ and other coexisting things.”[41] Black art, in all its earthly perversity, emerges in the absence and refusal of the capacity to claim difference as separation, as that which instead touches and is touched by the beauty and terrors of entanglement, “a composition which is always already a recomposition and a decomposition of prior and posterior compositions.”[42] Whatever its (anti-)formal qualities, black art proceeds from enfleshment, from the immanent brutalities and minor experiments of the haptic, the cuts and woundings of which it cannot help but bear. Black art materializes in and as a metaphysical impossibility, as that which, in Moten’s words, “might pierce the distinction between the biological and the symbolic…as the continual disruption of the very idea of (symbolic) value, which moves by way of the reduction of substance…[as] the reduction to substance (body to flesh) is inseparable from the reduction of substance.”[43] Hapticality is a way of naming an analytics of touch that cannot be, let alone appear, within the onto-epistemological confines of the (moribund) world, a gesture with and towards the abyssal revolution and devolution of the sensorium to which black people have already been subject, an enfleshment of the “difference without separability”[44] that has been and will be the condition of possibility for “life in the ruins.”[45]

_____

Rizvana Bradley is Assistant Professor of Film and Media at UC Berkeley. Her research and teaching focuses on the study of contemporary art and aesthetics at the intersections of film, literature, poetry, contemporary art and performance. Her scholarly approach to artistic practices in global black cultural production expands and develops frameworks for thinking across these contexts, specifically in relation to contemporary aesthetic theory. She has published articles in TDR: The Drama Review, Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, Black Camera: An International Film Journal, and Film Quarterly, and is currently working on two book projects.

_____

[1] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 1.

[2] Ibid., back cover.

[3] Ibid., 6.

[4] Ibid., 13.

[5] Ibid., 14.

[6] Ibid., 14-15.

[7] Ibid., 15.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 16, 17.

[10] Ibid., 21.

[11] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception (New York: Routledge, 2012), 73.

[12] Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks (London: Pluto Press, 1986).

[13] See, in particular, Frank B. Wilderson III, Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

[14] Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000). My reading of Marks is in turn inestimably shaped by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s elaboration of hapticality in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York; Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013), 97-99; see also the special issue I guest edited for Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, “The Haptic: Textures of Performance,” vol. 24, no. 2-3 (2014).

[15] This was a formulation made by Hartman in our conversation during my curated event for the Serpentine Galleries, London. “Hapticality, Waywardness, and the Practice of Entanglement: A Study Day with Saidiya Hartman,” 8 July, 2017.

[16] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 266.

[17] Cf. Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, ed. Dirk J. Struik (New York: International Publishers, 1964).

[18] Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics, Volume 17, Number 2 (Summer 1987), 64-81, 67.

[19] Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 39. For a contrasting interpretation, see R.A. Judy’s brilliant, recently published, Sentient Flesh: Thinking in Disorder, Poiēsis in Black (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), xvi, 210: “flesh is with and not before the body and person, and the body and person are with and not before or even after the flesh.”

[20] Weheliye (2014), 39.

[21] Fred Moten, “Of Human Flesh: An Interview with R.A. Judy” (Part Two), b2o: An Online Journal (6 May 2020).

[22] Spillers (1987), 67.

[23] R.A. Judy takes up these questions surrounding flesh and what he terms “para-semiosis,” or “the dynamic of differentiation operating in multiple multiplicities of semiosis that converge without synthesis[,]” with characteristic erudition in Sentient Flesh (2020), xiiv.

[24] Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 13.

[25] Spillers (1987), 67.

[26] Fanon (1986). Gayle Solamon, Assuming a Body: Transgender and the Rhetorics of Masculinity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[27] Judy (2020), 207.

[28] Spillers (1987), 67. For one of Fred Moten’s more pointed engagements with this formulation from Spillers, see “The Touring Machine (Flesh Thought Inside Out),” in Stolen Life (consent not to be a single being) (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 161-182.

[29] Hortense Spillers, “To the Bone: Some Speculations on Touch,” There’s a Tear in the World: Touch After Finitude, Stedelijk Museum of Art and Studium Generale Rietveld Academy, 23 March 2018, keynote address.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Wilderson, 2010.

[34] Spillers (2018). As these quotations are drawn from Spillers’s talk rather than a published text, the emphasis placed on the word being is inferred from her spoken intonation.

[35] Moten (2018), 176.

[36] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 1997), 333.

[37] Moten and Harney (2013), 97.

[38] Fred Moten, Black and Blur (consent not to be a single being), (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), ix.

[39] Peter de Bolla, Art Matters (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 28.

[40] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement (London: Macmillan and Co., 1914), 184.

[41] Denise Ferreira da Silva, “The Scene of Nature,” in Justin Desautels-Stein & Christopher Tomlins (eds.), Searching for Contemporary Legal Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 275-289, 276. For an important study of modernity’s “racial regime of aesthetics,” see David Lloyd, Under Representation: The Racial Regime of Aesthetics (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019).

[42] Denise Ferreira da Silva, “In the Raw,” e-flux, Journal #93 (September 2018).

[43] Fred Moten (2018), 174.

[44] Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Difference without Separability,” Catalogue of the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo – INCERTEZA VIVA (2016), 57-65.

[45] Cf. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).