a review of Jack Linchuan Qiu, Goodbye iSlave: a Manifesto for Digital Abolition (Illinois, 2016)

by Zachary Loeb

~

With bright pink hair and a rainbow horn, the disembodied head of a unicorn bobs back and forth to the opening beats of Big Boi’s “All Night.” Moments later, a pile of poop appears and mouths the song’s opening words, and various animated animal heads appear nodding along in sequence. Soon the unicorn returns, lip-synching the song, and it is quickly joined by a woman whose movements, facial expressions, and exaggerated enunciations sync with those of the unicorn. As a pig, a robot, a chicken, and a cat appear to sing in turn it becomes clear that the singing emojis are actually mimicking the woman – the cat blinks when she blinks, it raises its brow when she does. The ad ends by encouraging users to “Animoji” themselves, something which is evidently doable with Apple’s iPhone X. It is a silly ad, with a catchy song, and unsurprisingly it tells the viewer nothing about where, how, or by whom the iPhone X was made. The ad may playfully feature the ever-popular “pile of poop” emoji, but the ad is not intended to make potential purchasers feel like excrement.

And yet there is much more to the iPhone X’s history than the words on the device’s back “Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China.” In Goodbye iSlave: a Manifesto for Digital Abolition, Jack Linchuan Qiu removes the phone’s shiny case to explore what “assembled in China” really means. As Qiu demonstrates in discomforting detail this is a story that involves exploitative labor practices, enforced overtime, abusive managers, insufficient living quarters, and wage theft, in a system that he argues is similar to slavery.

Launched by activists in 2010, the “iSlave” campaign aimed to raise awareness about the labor conditions that had led to a wave of suicides amongst Foxconn workers; those performing the labor summed up neatly as “assembled in China.” Seizing upon the campaign’s key term, Qiu aims to expand it “figuratively and literally” to demonstrate that “iSlavery” is “a planetary system of domination, exploitation, and alienation…epitomized by the material and immaterial structures of capital accumulation” (9). This in turn underscores the “world system of gadgets” that Qiu refers to as “Appconn” (13); a system that encompasses those who “designed” the devices, those who “assembled” them, as well as those who use them. In engaging with the terminology of slavery, Qiu is consciously laying out a provocative argument, but it is a provocation that acknowledges that as smartphones have become commonplace many consumers have become inured to the injustices that allow them to “animoji” themselves. Indeed, it is a reminder that, “Technology does not guarantee progress. It is, instead, often abused to cause regress” (8).

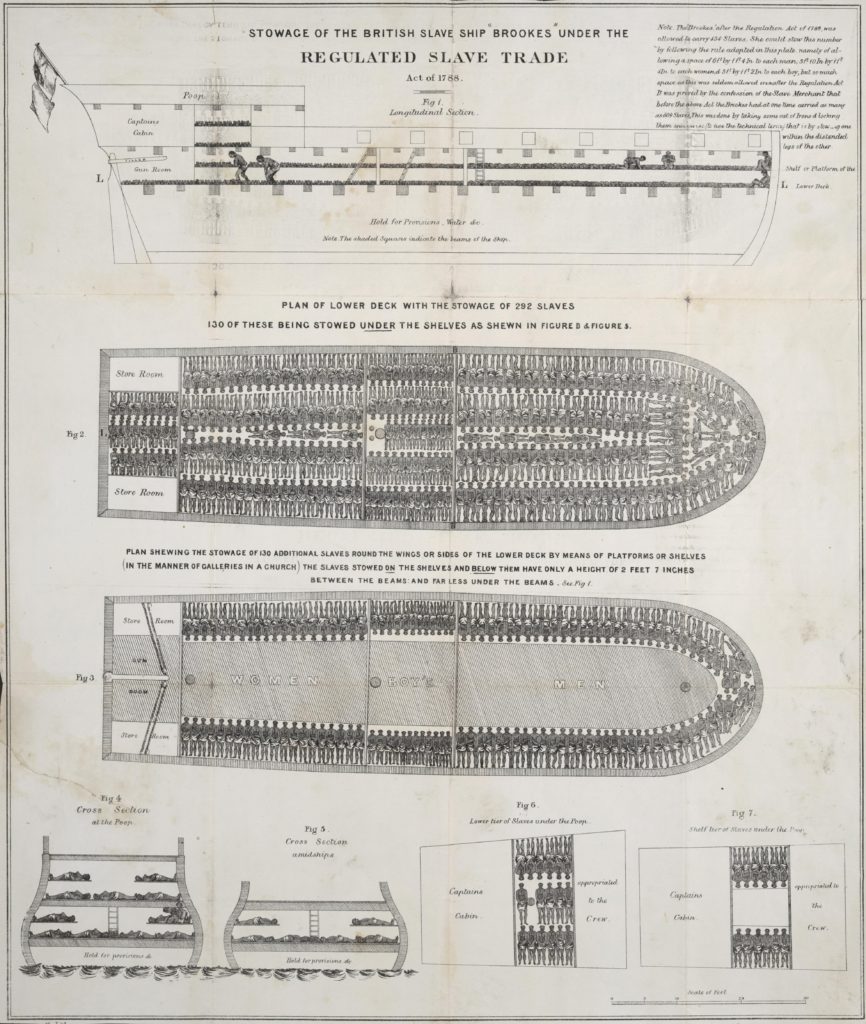

Surveying its history, Qiu notes that slavery has appeared in a variety of forms in many regions throughout history. Though he emphasizes that even today slavery “persists in its classic forms” (21), his focus remains on theoretically expanding the term. Qiu draws upon the League of Nation’s “1926 Slavery Convention” which still acts as the foundation for much contemporary legal thinking on slavery, including the 2012 Bellagio-Harvard Guidelines on the Legal Parameters of Slavery (which Qiu includes in his book as an appendix). These legal guidelines expand the definition of what constitutes slavery to include “institutions and practices similar to slavery” (42). The key element for this updated definition is an understanding that it is no longer legal for a person to be “formally and legally ‘owned’ in any jurisdiction” and thus the concept of slavery requires rethinking (45). In considering which elements from the history of slavery are particularly relevant for the story of “iSlavery,” Qiu emphasizes: how the slave trade made use of advanced technologies of its time (guns, magnetic compasses, slave ships); how the slave trade was linked to creating and satisfying consumer desires (sugar); and how the narrative of resistance and revolt is a key aspect of the history of slavery. For Qiu, “iSlavery” is manifested in two forms: “manufacturing iSlaves” and “manufactured iSlaves.”

In the process of creating high-tech gadgets there are many types of “manufacturing iSlaves,” in conditions similar to slavery “in its classic forms” including “Congolese mine workers” and “Indonesian child labor,” but Qiu focuses primarily on those working for Foxconn in China. Drawing upon news reports, NGO findings, interviews with former workers, underground publications produced by factor workers, and from his experiences visiting these assembly plants, Qiu investigates many ways in which “institutions and practices similar to slavery” shape the lives of Foxconn workers. Insufficient living conditions, low wages that are often not even paid, forced overtime, “student interns” being used as an even cheaper labor force, violently abusive security guards, the arrangement of life so as to maximize disorientation and alienation – these represent some of the common experiences of Foxconn workers. Foxconn found itself uncomfortably in the news in 2010 due to a string of worker suicides, and Qiu sympathetically portrays the conditions that gave rise to such acts, particularly in his interview with Tian Yu who survived her suicide attempt.

As Qiu makes clear, Foxconn workers often have great difficulty leaving the factories, but what exits these factories at a considerable rate are mountains of gadgets that go on to be eagerly purchased and used by the “manufactured iSlaves.” The transition to the “manufactured iSlave” entails “a conceptual leap” (91) that moves away from the “practices similar to slavery” that define the “manufacturing iSlave” to instead signify “those who are constantly attached to their gadgets” (91). Here the compulsion takes on the form of a vicious consumerism that has resulted in an “addiction” to these gadgets, and a sense in which these gadgets have come to govern the lives of their users. Drawing upon the work of Judy Wajcman, Qiu notes that “manufactured iSlaves” (Qiu’s term) live under the aegis of “iTime” (Wajcman’s term), a world of “consumerist enslavement” into which they’ve been drawn by “Net Slaves” (Steve Baldwin and Bill Lessard’s term of “accusation and ridicule” for those whose jobs fit under the heading “Designed in California”). While some companies have made fortunes off the material labor of “manufacturing iSlaves,” Qiu emphasizes that many companies that have made their fortunes off the immaterial labor of legions of “manufactured iSlaves” dutifully clicking “like,” uploading photos, and hitting “tweet” all without any expectation that they will be paid for their labor. Indeed, in Qiu’s analysis, what keeps many “manufactured iSlaves” unaware of their shackles is that they don’t see what they are doing on their devices as labor.

In his description of the history of slavery, Qiu emphasizes resistance, both in terms of acts of rebellion by enslaved peoples, and the broader abolition movement. This informs Qiu’s commentary on pushing back against the system of Appconn. While smartphones may be cast as the symbol of the exploitation of Foxconn workers, Qiu also notes that these devices allow for acts of resistance by these same workers “whose voices are increasingly heard online” (133). Foxconn factories may take great pains to remain closed off from prying eyes, but workers armed with smartphones are “breaching the lines of information lockdown” (148). Campaigns by national and international NGOs can also be important in raising awareness of the plight of Foxconn workers, after all the term “iSlave” was originally coined as part of such a campaign. In bringing awareness of the “manufacturing iSlave” to the “manufactured iSlave” Qiu points to “culture jamming” responses such as the “Phone Story” game which allows people to “play” through their phones vainglorious tale (ironically the game was banned from Apple’s app store). Qiu also points to the attempt to create ethical gadgets, such as the Fairphone which aims to responsibly source its minerals, pay those who assemble their phones a living wage, and push back against the drive of planned obsolescence. As Qiu makes clear, there are many working to fight against the oppression built into Appconn.

“For too long,” Qiu notes, “the underbellies of the digital industries have been obscured and tucked away; too often, new media is assumed to represent modernity, and modernity assumed to represent freedom” (172). Qiu highlights the coercion and misery that are lurking below the surface of every silly cat picture uploaded on Instagram, and he questions whether the person doing the picture taking and uploading is also being exploited. A tough and confrontational book, Goodbye iSlave nevertheless maintains hope for meaningful resistance.

Anyone who has used a smartphone, tablet, laptop computer, e-reader, video game console, or smart speaker would do well to read Goodbye iSlave. In tight effective prose, Qiu presents a gripping portrait of the lives of Foxconn workers and this description is made more confrontational by the uncompromising language Qiu deploys. And though Qiu begins his book by noting that “the outlook of manufacturing and manufactured iSlaves is rather bleak” (18), his focus on resistance gives his book the feeling of an activist manifesto as opposed to the bleak tonality of a woebegone dirge. By engaging with the exploitation of material labor and immaterial labor, Qiu is, furthermore, able to uncomfortably remind his readers not only that their digital freedom comes at a human cost, but that digital freedom may itself be a sort of shackle.

In the book’s concluding chapter, Qiu notes that he is “fully aware that slavery is a very severe critique” (172), and this represents one of the greatest challenges the book poses. Namely: what to make of Qiu’s use of the term slavery? As Qiu demonstrates, it is not a term that he arrived at simply for shock value, nevertheless, “slavery” is itself a complicated concept. Slavery carries a history of horrors that make one hesitant to deploy it in a simplistic fashion even as it remains a basic term of international law. By couching his discussion of “iSlavery” both in terms of history and contemporary legal thinking, Qiu demonstrates a breadth of sensitivity and understanding regarding its nuances. And given the focus of current laws on “institutions and practices similar to slavery” (42) it is hard to dispute that this is a fair description of many of the conditions to which Foxconn workers are subjected – even as Qiu’s comments on coltan miners demonstrates other forms of slavery that lurk behind the shining screens of high-tech society.

Nevertheless, there is frequently something about the use of the term “iSlavery” that seems to diminish the heft of Qiu’s argument. As the term often serves as a stumbling block that pulls a reader away from Qiu’s account; particularly when he tries to make the comparisons too direct such as juxtaposing Foxconn’s (admittedly wretched) dormitories to conditions on slave ships crossing the Atlantic. It’s difficult not to find the comparison hyperbolic. Similarly, Qiu notes that ethnic and regional divisions are often found within Foxconn factories; but these do not truly seem comparable to the racist views that undergirded (and was used to justify) the Atlantic slave trade. Unfortunately, this is a problem that Qiu sets for himself: had he only used “slave” in a theoretical sense it would have opened him to charges of historical insensitivity, but by engaging with the history of slavery many of Qiu’s comparisons seem to miss the mark – and this is exacerbated by the fact that he repeatedly refers to ongoing conditions of “classic” slavery involved in the making of gadgets (such as coltan mining). Qiu provides an important and compelling window into the current legal framing of slavery, and yet, something about the “iSlave” prevents it from fitting into the history of slavery. It is, unfortunately, too easy to imagine someone countering Qiu’s arguments by saying “but this isn’t really slavery” to which the retort of “current law defines slavery as…” will be unlikely to convince.

The matter of “slavery” only gets thornier as Qiu shifts his attention from “manufacturing iSlaves” to “manufactured iSlaves.” In recent years there has been a wealth of writing in the academic and popular sphere that critically asks what our gadgets are doing to us, such as Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together and Judy Wacjman’s Pressed for Time (which Qiu cites). And the fear that technology turns people into “cogs” is hardly new: in his 1956 book The Sane Society, Erich Fromm warned “the danger of the past was that men became slaves. The danger of the future is that men may become robots” (Fromm, 352). Fromm’s anxiety is what one more commonly encounters in discussions about what gadgets turn their users into, but these “robots” are not identical with “slaves.” When Qiu discusses “manufactured iSlaves” he notes that it represents a “conceptual leap,” but by continuing to use the term “slave” this “conceptual leap” unfortunately hampers his broader points about Foxconn workers. The danger is that a sort of false equivalency risks being created in which smartphone users shrug off their complicity in the exploitation of assembly workers by saying, “hey, I’m exploited too.”

Some of this challenge may ultimately simply be about word choice. The very term “iSlave,” despite its activist origins, seems somewhat silly through its linkage to all things to which a lowercase “i” has been affixed. Furthermore, the use of the “i” risks placing all of the focus on Apple. True, Apple products are manufactured in the exploitative Foxconn factories, and Qiu may be on to something in referring to the “Apple cult,” but as Qiu himself notes Foxconn manufactures products for a variety of companies. Just because a device isn’t an “i” gadget, doesn’t mean that it wasn’t manufactured by an “iSlave.” And while Appconn is a nice shorthand for the world that is built upon the backs of both kinds of “iSlaves” it risks being just another opaque neologism for computer dominated society that is undercut by the need for it to be defined.

Given the grim focus of Qiu’s book, it is understandable why he should choose to emphasize rebellion and resistance, and these do allow readers to put down the book feeling energized. Yet some of these modes of resistance seem to risk more entanglement than escape. There is a risk that the argument that Foxconn workers can use smartphones to organize simply fits neatly back into the narrative that there is something “inherently liberating” about these devices. The “Phone Story” game may be a good teaching tool, but it seems to make a similar claim on the democratizing potential of the Internet. And while the Fairphone represents, perhaps, one of the more significant ways to get away from subsidizing Appconn it risks being just an alternative for concerned consumers not a legally mandated industry standard. At risk of an unfair comparison, a Fairphone seems like the technological equivalent of free range eggs purchased at the farmer’s market – it may genuinely be ethically preferable, but it risks reducing a major problem (iSlavery) into yet another site for consumerism (just buy the right phone). In fairness, these are the challenges inherent in critiquing the dominant order; as Theodor Adorno once put it “we live on the culture we criticize” (Adorno and Horkheimer, 105). It might be tempting to wish that Qiu had written an Appconn version of Jerry Mander’s Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, but Qiu seems to recognize that simply telling people to turn it all off is probably just as efficacious as telling them not to do anything at all. After all, Mander’s “four arguments” may have convinced a few people – but not society as a whole. So, what then does “digital abolition” really mean?

In describing Goodbye iSlave, Qiu notes that it is “nothing more than an invitation—for everyone to reflect on the enslaving tendencies of Appconn and the world system of gadgets” it is an opportunity for people to reflect on the ways in which “so many myths of liberation have been bundled with technological buzzwords, and they are often taken for granted” (173). It is a challenging book and an important one, and insofar as it forces readers to wrestle with Qiu’s choice of terminology it succeeds by making them seriously confront the regimes of material and immaterial labor that structure their lives. While the use of the term “slavery” may at times hamper Qiu’s larger argument, this unflinching look at the labor behind today’s gadgets should not be overlooked.

Goodbye iSlave frames itself as “a manifesto for digital abolition,” but what it makes clear is that this struggle ultimately isn’t about “i” but about “us.”

_____

Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, an MA from the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU, and is currently working towards a PhD in the History and Sociology of Science department at the University of Pennsylvania. His research areas include media refusal and resistance to technology, ideologies that develop in response to technological change, and the ways in which technology factors into ethical philosophy – particularly in regards of the way in which Jewish philosophers have written about ethics and technology. Using the moniker “The Luddbrarian,” Loeb writes at the blog Librarian Shipwreck, and is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

Back to the essay

_____

Works Cited

- Adorno, Theodor and Horkheimer, Max. 2011. Towards a New Manifesto. London: Verso Books.

- Fromm, Erich. 2002. The Sane Society. London: Routledge.