This essay has been peer-reviewed by “The New Extremism” special issue editors (Adrienne Massanari and David Golumbia), and the b2o: An Online Journal editorial board.

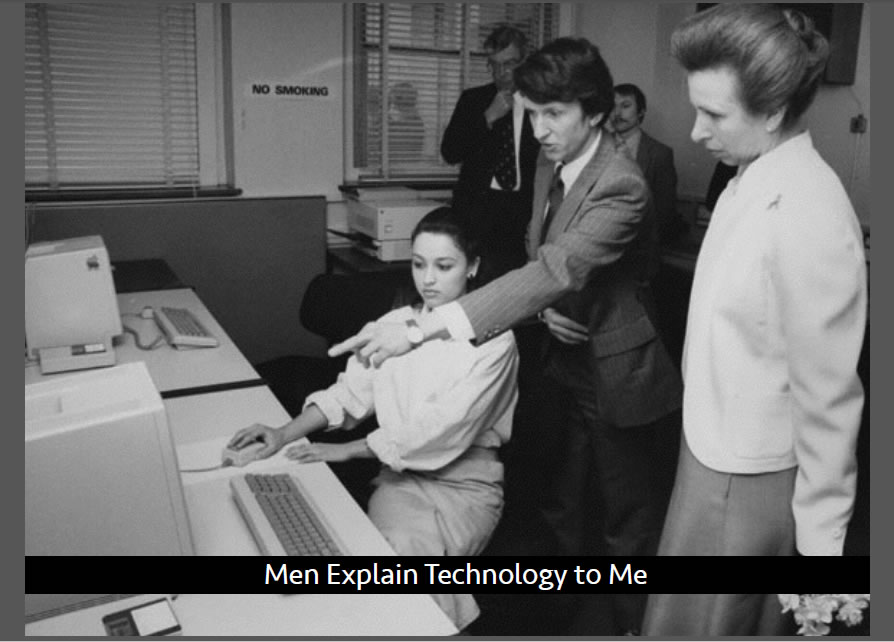

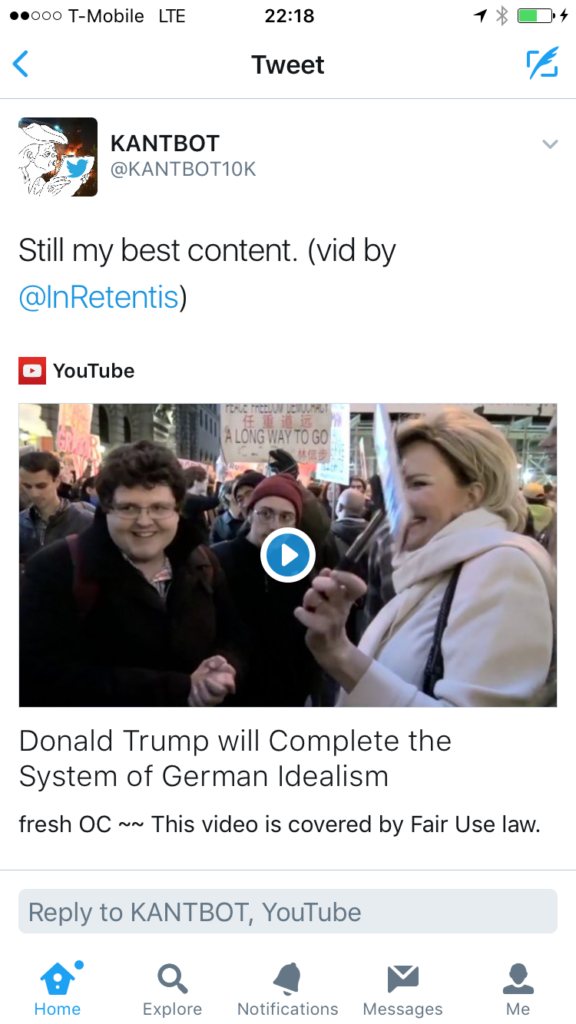

Take three minutes to watch this clip from a rally in New York City just after the 2016 presidential election.[i] In the impromptu interview, we learn that Donald Trump is going to “raise the ancient city of Thule” and “complete the system of German Idealism.” In what follows, I’m going to interpret what the troll in the video—known only by his twitter handle, @kantbot2000—is doing here. It involves Donald Trump, German Idealism, metaphysics, social media, and above all irony. It’s a diagnosis of the current relationship between mediated speech and politics. I’ll come back to Kantbot presently, but first I want to lay the scene he’s intervening in.

A small but deeply networked group of self-identifying trolls and content-producers has used the apparently unlikely rubric of German philosophy to diagnose our media-rhetorical situation. There’s less talk of trolls now than there was in 2017, but that doesn’t mean they’re gone.[ii] Take the recent self-introductory op-ed by Brazil’s incoming foreign minister, Ernesto Araùjo, which bizarrely accuses Ludwig Wittgenstein of undermining the nationalist identity of Brazilians (and everyone else). YouTube remains the global channel of this Alt Right[iii] media game, as Andre Pagliarini has documented: one Olavo de Carvalho, whose channel is dedicated to the peculiar philosophical obsessions of the global Alt Right, is probably responsible for this foreign minister taking the position, apparently intended as policy, “I don’t like Wittgenstein,” and possibly for his appointment in the first place. The intellectuals playing this game hold that Marxist and postmodern theory caused the political world to take its present shape, and argue that a wide variety of theoretical tools should be reappropriated to the Alt Right. This situation presents a challenge to the intellectual Left on both epistemological and political grounds.

The core claim of this group—one I think we should take seriously—is that mediated speech is essential to politics. In a way, this claim is self-fulfilling. Araùjo, for example, imagines that Wittgenstein’s alleged relativism is politically efficacious; Wittgenstein arrives pre-packaged by the YouTube phenomenon Carvalho; Araùjo’s very appointment seems to have been the result of Carvalho’s influence. That this tight ideological loop should realize itself by means of social media is not surprising. But in our shockingly naïve public political discussions—at least in the US—emphasis on the constitutive role of rhetoric and theory appears singular. I’m going to argue that a crucial element of this scene is a new tone and practice of irony that permeates the political. This political irony is an artefact of 2016, most directly, but it lurks quite clearly beneath our politics today. And to be clear, the self-styled irony of this group is never at odds with a wide variety of deeply held, and usually vile, beliefs. This is because irony and seriousness are not, and have never been, mutually exclusive. The idea that the two cannot cohabit is one of the more obvious weak points of our attempt to get an analytical foothold on the global Alt Right—to do so, we must traverse the den of irony.

Irony has always been a difficult concept, slippery to the point of being undefinable. It usually means something like “when the actual meaning is the complete opposite from the literal meaning,” as Ethan Hawke tells Wynona Ryder in 1994’s Reality Bites. Ryder’s plaint, “I know it when I see it” points to just how many questions this definition raises. What counts as a “complete opposite”? What is the channel—rhetorical, physical, or otherwise—by which this dual expression can occur? What does it mean that what we express can contain not only implicit or connotative content, but can in fact make our speech contradict itself to some communicative effect? And for our purposes, what does it mean when this type of question embeds itself in political communication?

Virtually every major treatment of irony since antiquity—from Aristotle to Paul de Man—acknowledges these difficulties. Quintilian gives us the standard definition: that the meaning of a statement is in contradiction to what it literally extends to its listener. But he still equivocates about its source:

eo vero genere, quo contraria ostenduntur, ironia est; illusionem vocant. quae aut pronuntiatione intelligitur aut persona aut rei nature; nam, si qua earum verbis dissentit, apparet diversam esse orationi voluntatem. Quanquam id plurimis id tropis accidit, ut intersit, quid de quoque dicatur, quia quoddicitur alibi verum est.

On the other hand, that class of allegory in which the meaning is contrary to that suggested by the words, involve an element of irony, or, as our rhetoricians call it, illusio. This is made evident to the understanding either by the delivery, the character of the speaker or the nature of the subject. For if any one of these three is out of keeping with the words, it at once becomes clear that the intention of the speaker is other than what he actually says. In the majority of tropes it is, however, important to bear in mind not merely what is said, but about whom it is said, since what is said may in another context be literally true. (Quintilian 1920, book VIII, section 6, 53-55)

Speaker, ideation, context, addressee—all of these are potential sources for the contradiction. In other words, irony is not limited to the intentional use of contradiction, to a wit deploying irony to produce an effect. Irony slips out of precise definition even in the version that held sway for more than a millennium in the Western tradition.

I’m going to argue in what follows that irony of a specific kind has re-opened what seemed a closed channel between speech and politics. Certain functions of digital, and specifically social, media enable this kind of irony, because the very notion of a digital “code” entailed a kind of material irony to begin with. This type of irony can be manipulated, but also exceeds anyone’s intention, and can be activated accidentally (this part of the theory of irony comes from the German Romantic Friedrich Schlegel, as we will see). It not only amplifies messages, but does so by resignifying, exploiting certain capacities of social media. Donald Trump is the master practitioner of this irony, and Kantbot, I’ll propose, is its media theorist. With this irony, political communication has exited the neoliberal speech regime; the question is how the Left responds.

i. “Donald Trump Will Complete the System of German Idealism”

Let’s return to our video. Kantbot is trolling—hard. There’s obvious irony in the claim that Trump will “complete the system of German Idealism,” the philosophical network that began with Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and ended (at least on Kantbot’s account) only in the 1840s with Friedrich Schelling’s philosophy of mythology. Kant is best known for having cut a middle path between empiricism and rationalism. He argued that our knowledge is spontaneous and autonomous, not derived from what we observe but combined with that observation and molded into a nature that is distinctly ours, a nature to which we “give the law,” set off from a world of “things in themselves” about which we can never know anything. This philosophy touched off what G.W.F. Hegel called a “revolution,” one that extended to every area of human knowledge and activity. History itself, Hegel would famously claim, was the forward march of spirit, or Geist, the logical unfolding of self-differentiating concepts that constituted nature, history, and institutions (including the state). Schelling, Hegel’s one-time roommate, had deep reservations about this triumphalist narrative, reserving a place for the irrational, the unseen, the mythological, in the process of history. Hegel, according to a legend propagated by his students, finished his 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit while listening to the guns of the battle of Auerstedt-Jena, where Napoleon defeated the Germans and brought a final end to the Holy Roman Empire. Hegel saw himself as the philosopher of Napoleon’s moment, at least in 1807; Kantbot sees himself as the Hegel to Donald Trump (more on this below).

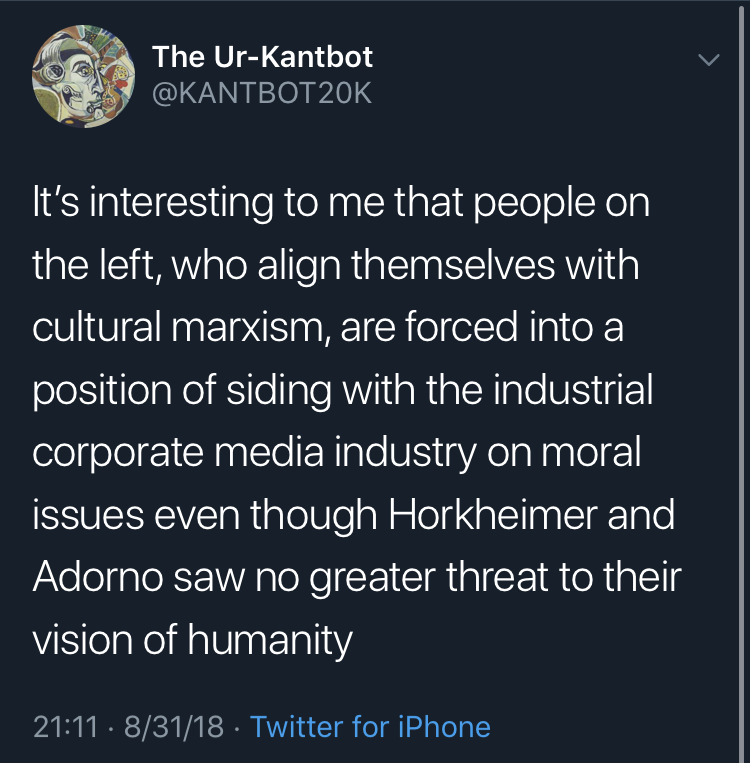

Rumor has it that Kantbot is an accountant in NYC, although no one has been able to doxx him yet. His twitter has more than 26,000 followers at the time of writing. This modest fame is complemented by a deep lateral network among the biggest stars on the Far Right. To my eye he has made little progress in gaining fame—but also in developing his theory, on which he has recently promised a book “soon”—in the last year. Conservative media reported that he was interviewed by the FBI in 2018. His newest line of thought involves “hate hoaxes” and questioning why he can’t say the n-word—a regression to platitudes of the extremist Right that have been around for decades, as David Neiwert has extensively documented (Neiwert 2017). Sprinkled between these are exterminationist fantasies—about “Spinozists.” He toggles between conspiracy, especially of the false-flag variety, hate-speech-flirtation, and analysis. He has recently started a podcast. The whole presentation is saturated in irony and deadly serious:

Asked how he identifies politically, Kantbot recently claimed to be a “Stalinist, a TERF, and a Black Nationalist.” Mike Cernovich, the Alt Right leader who runs the website Danger and Play, has been known to ask Kantbot for advice. There is also an indirect connection between Kantbot and “Neoreaction” or NRx, a brand of “accelerationism” which itself is only blurrily constituted by the blog-work of Curtis Yarvin, aka Mencius Moldbug and enthusiasm for the philosophy of Nick Land (another reader of Kant). Kantbot also “debated” White Nationalist thought leader Richard Spencer, presenting the spectacle of Spencer, who wrote a Masters thesis on Adorno’s interpretation of Wagner, listening thoughtfully to Kantbot’s explanation of Kant’s rejection of Johann Gottfried Herder, rather than the body count, as the reason to reject Marxism.

When conservative pundit Ann Coulter got into a twitter feud with Delta over a seat reassignment, Kantbot came to her defense. She retweeted the captioned image below, which was then featured on Breitbart News in an article called “Zuckerberg 2020 Would be a Dream Come True for Republicans.”

Kantbot’s partner-in-crime, @logo-daedalus (the very young guy in the maroon hat in the video) has recently jumped on a minor fresh wave of ironist political memeing in support of UBI-focused presidential candidate, Andrew Yang – #yanggang. He was once asked by Cernovich if he had read Michael Walsh’s book, The Devil’s Pleasure Palace: The Cult of Critical Theory and the Subversion of the West:

The autodidact intellectualism of this Alt Right dynamic duo—Kantbot and Logodaedalus—illustrates several roles irony plays in the relationship between media and politics. Kantbot and Logodaedalus see themselves as the avant-garde of a counterculture on the brink of a civilizational shift, participating in the sudden proliferation of “decline of the West” narratives. They alternate targets on Twitter, and think of themselves as “producers of content” above all. To produce content, according to them, is to produce ideology. Kantbot is singularly obsessed the period between about 1770 and 1830 in Germany. He thinks of this period as the source of all subsequent intellectual endeavor, the only period of real philosophy—a thesis he shares with Slavoj Žižek (Žižek 1993).

This notion has been treated monographically by Eckart Förster in The Twenty-Five Years of Philosophy, a book Kantbot listed in May of 2017 under “current investigations.” His twist on the thesis is that German Idealism is saturated in a form of irony. German Idealism never makes culture political as such. Politics comes from a culture that’s more capacious than any politics, so any relation between the two is refracted by a deep difference that appears, when they are brought together, as irony. Marxism, and all that proceeds from Marxism, including contemporary Leftism, is a deviation from this path.

This reading of German Idealism is a search for the metaphysical origins of a common conspiracy theory in the Breitbart wing of the Right called “cultural Marxism” (the idea predates Breibart: see Jay 2011; Huyssen 2017; Berkowitz 2003. Walsh’s 2017 The Devil’s Pleasure Palace, which LogoDaedalus mocked to Cernovich, is one of the touchstones of this theory). Breitbart’s own account states that there is a relatively straight line from Hegel’s celebration of the state to Marx’s communism to Woodrow Wilson’s and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s communitarianism—and on to critical theory of Theodor W. Adorno and Herbert Marcuse (this is the actual “cultural Marxism,” one supposes), Saul Alinsky’s community organizing, and (surprise!) Barack Obama’s as well (Breitbart 2011, 105-37). The phrase “cultural Marxism” is a play on the Nazi phrase “cultural Bolshevism,” a conspiracy theory that targeted Jews as alleged spies and collaborators of Stalin’s Russia. The anti-Semitism is only slightly more concealed in the updated version. The idea is that Adorno and Marcuse took control of the cultural matrix of the United States and made the country “culturally communist.” In this theory, individual freedom is always second to an oppressive community in the contemporary US. Between Breitbart’s adoption of critical theory and NRx (see Haider 2017; Beckett 2017; Noys 2014)—not to mention the global expansion of this family of theories by figures like Carvalho—it’s clear that the “Alt Right” is a theory-deep assemblage. The theory is never just analysis, though. It’s always a question of intervention, or media manipulation (see Marwick and Lewis 2017).

Breitbart himself liked to capture this blend in his slogan “politics is downstream from culture.” Breitbart’s news organization implicitly cedes the theoretical point to Adorno and Marcuse, trying to build cultural hegemony in the online era. Reform the cultural, dominate the politics—all on the basis of narrative and media manipulation. For the Alt Right, politics isn’t “online” or “not,” but will always be both.

In mid-August of 2017, a flap in the National Security Council was caused by a memo, probably penned by staffer Rich Higgins (who reportedly has ties to Cernovich), that appeared to accuse then National Security Adviser, H. R. McMaster, of supporting or at least tolerating Cultural Marxism’s attempt to undermine Trump through narrative (see Winter and Groll 2017). Higgins and other staffers associated with the memo were fired, a fact which Trump learned from Sean Hannity and which made him “furious.” The memo, about which the president “gushed,” defines “the successful outcome of cultural Marxism [as] a bureaucratic state beholden to no one, certainly not the American people. With no rule of law considerations outside those that further deep state power, the deep state truly becomes, as Hegel advocated, god bestriding the earth” (Higgins 2017). Hegel defined the state as the goal of all social activity, the highest form of human institution or “objective spirit.” Years later, it is still Trump vs. the state, in its belated thrall to Adorno, Marcuse, and (somehow) Hegel. Politics is downstream from German Idealism.

Kantbot’s aspiration was to expand and deepen the theory of this kind of critical manipulation of the media—but he wants to rehabilitate Hegel. In Kantbot’s work we begin to glimpse how irony plays a role in this manipulation. Irony is play with the very possibility of signification in the first place. Inflected through digital media—code and platform—it becomes not just play but its own expression of the interface between culture and politics, overlapping with one of the driving questions of the German cultural renaissance around 1800. Kantbot, in other words, diagnosed and (at least at one time) aspired to practice a particularly sophisticated combination of rhetorical and media theory as political speech in social media.

Consider this tweet:

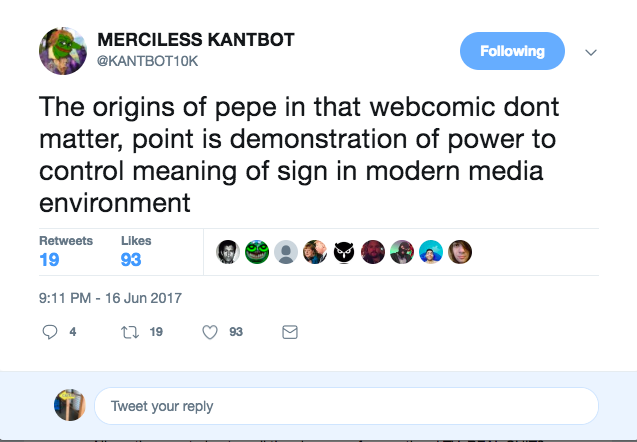

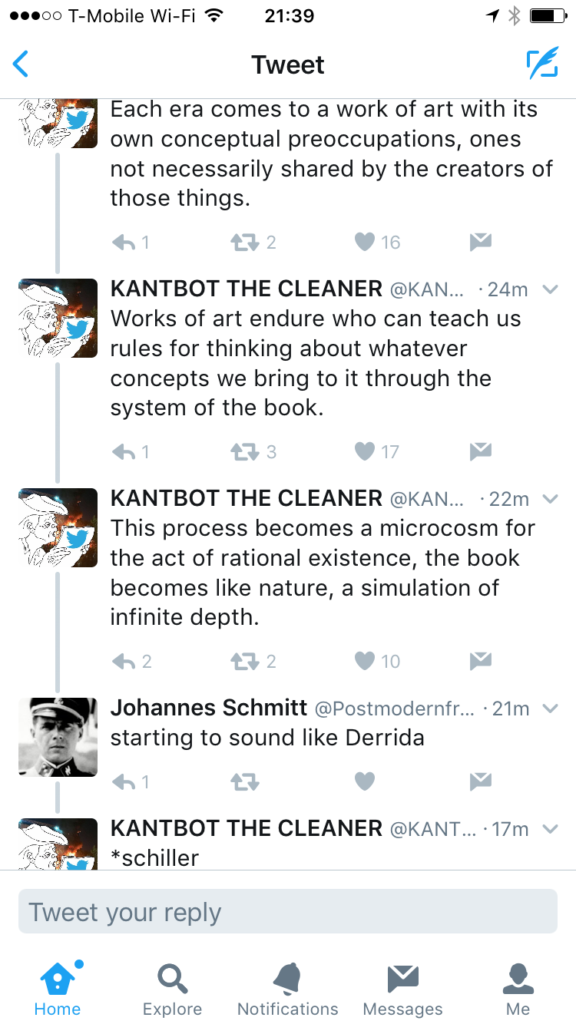

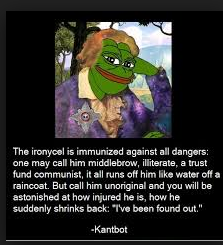

After an innocuous webcomic frog became infamous in 2016, after the Clinton campaign denounced its use and the Anti-Defamation League took the extraordinary step of adding the meme to its Hate Database, Pepe the Frog gained a kind of cult status. Kantbot’s reading of the phenomenon is that the “point is demonstration of power to control meaning of sign in modern media environment.” If this sounds like French Theory, then one “Johannes Schmitt” (whose profile thumbnail appears to be an SS officer) agrees. “Starting to sound like Derrida,” he wrote. To which Kantbot responds, momentously: “*schiller.”

The asterisk-correction contains multitudes. Kantbot is only too happy to jettison the “theory,” but insists that the manipulation of the sign in its relation to the media environment maintains and alters the balance between culture and politics. Friedrich Schiller, whose classical aesthetic theory claims just this, is a recurrent figure for Kantbot. The idea, it appears, is to create a culture that is beyond politics and from which politics can be downstream. To that end, Kantbot opened his own online venue, the “Autistic Mercury,” named after Der teutsche Merkur, one of the German Enlightenment’s central organs.[iv] For Schiller, there was a “play drive” that mediated between “form” and “content” drives. It preserved the autonomy of art and culture and had the potential to transform the political space, but only indirectly. Kantbot wants to imitate the composite culture of the era of Kant, Schiller, and Hegel—just as they built their classicism on Johann Winckelmann’s famous doctrine that an autonomous and inimitable culture must be built on imitation of the Greeks. Schiller was suggesting that art could prevent another post-revolutionary Terror like the one that had engulfed France. Kantbot is suggesting that the metaphysics of communication—signs as both rhetoric and mediation—could resurrect a cultural vitality that got lost somewhere along the path from Marx to the present. Donald Trump is the instrument of that transformation, but its full expression requires more than DC politics. It requires (online) culture of the kind the campaign unleashed but the presidency has done little more than to maintain. (Kantbot uses Schiller for his media analysis too, as we will see.) Spencer and Kanbot agreed during their “debate” that perhaps Trump had done enough before he was president to justify the disappointing outcomes of his actual presidency. Conservative policy-making earns little more than scorn from this crowd, if it is detached from the putative real work of building the Alt Right avant-garde.

According to one commenter on YouTube, Kantbot is “the troll philosopher of the kek era.” Kek is the god of the trolls. His name is based on a transposition of the letters LOL in the massively-multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft. “KEK” is what the enemy sees when you laugh out loud to someone on your team, in an intuitively crackable code that was made into an idol to worship. Kek—a half-fake demi-God—illustrates the balance between irony and ontology in the rhetorical media practice known as trolling.

The name of the idol, it turned out, was also the name of an actual ancient Egyptian demi-god (KEK), a phenomenon that confirmed his divine status, in an example of so-called “meme magic.” Meme magic is when—often by praying to KEK or relying on a numerological system based on the random numbers assigned to users of 4Chan and other message boards—something that exists only online manifests IRL, “in real life” (Burton 2016). Examples include Hillary Clinton’s illness in the late stages of the campaign (widely and falsely rumored—e.g. by Cernovich—before a real yet minor illness was confirmed), and of course Donald Trump’s actual election. Meme magic is everywhere: it names the channel between online and offline.

Meme magic is both drenched in irony and deeply ontological. What is meant is just “for the lulz,” while what is said is magic. This is irony of the rhetorical kind—right up until it works. The case in point is the election, where the result, and whether the trolls helped, hovers between reality and magic. First there is meme generation, usually playfully ironic. Something happens that resembles the meme. Then the irony is retroactively assigned a magical function. But statements about meme magic are themselves ironic. They use the contradiction between reality and rhetoric (between Clinton’s predicted illness and her actual pneumonia) as the generator of a second-order irony (the claim that Trump’s election was caused by memes is itself a meme). It’s tempting to see this just as a juvenile game, but we shouldn’t dismiss the way the irony scales between the different levels of content-production and interpretation. Irony is rhetorical and ontological at once. We shouldn’t believe in meme magic, but we should take this recursive ironizing function very seriously indeed. It is this kind of irony that Kantbot diagnoses in Trump’s manipulation of the media.

ii. Coding Irony: Friedrich Schlegel, Claude Shannon, and Twitter

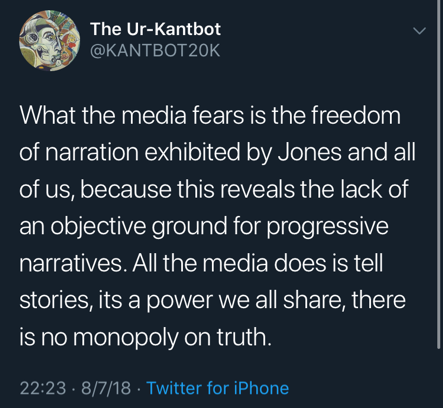

The ongoing inability of the international press to cover Donald Trump in a way that measures the impact of his statements rather than their content stems from this use of irony. We’ve gotten used to fake news and hyperbolic tweets—so used to these that we’re missing the irony that’s built in. Every time Trump denies something about collusion or says something about the coal industry that’s patently false, he’s exploiting the difference between two sets of truth-valuations that conflict with one another (e.g. racism and pacifism). That splits his audience—something that the splitting of the message in irony allows—and works both to fight his “enemies” and to build solidarity in his base. Trump has changed the media’s overall expression, making not his statements but the very relation between content and platform ironic. This objective form of media irony is not to be confused with “wit.” Donald Trump is not “witty.” He is, however, a master of irony as a tool for manipulation built into the way digital media allow signification to occur. He is the master of an expanded sense of irony that runs throughout the history of its theory.

When White Nationalists descended on Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 11, 2017, leading to the death of one counter-protester the next day, Trump dragged his feet in naming “racism.” He did, eventually, condemn the groups by name—prefacing his statements with a short consideration of the economy, a dog-whistle about what comes first (actually racism, for which “economy” has become an erstwhile cipher). In the interim, however, his condemnations of violence “as such” led Spencer to tweet this:

Of course, two days later, Trump would explicitly blame the “Alt Left” for violence it did not commit. Before that, however, Spencer’s irony here relied on Trump’s previous—malicious—irony. By condemning “all” violence when only one kind of violence was at issue, Trump was attempting to split the signal of his speech. The idea was to let the racists know that they could continue through condemnation of their actions that pays lip service to the non-violent ideal of the liberal media. Spencer gleefully used the internal contradiction of Trump’s speech, calling attention to the side of the message that was supposed to be “hidden.” Even the apparently non-ironic condemnation of “both sides” exploited a contradiction not in the statement itself, but in the way it is interpreted by different outlets and political communities. Trump’s invocation of the “Alt Left” confirmed the suspicions of those on the Right, panics the Center, and all but forced the Left to adopt the term. The filter bubbles, meanwhile, allowed this single message to deliver contradictory meanings on different news sites—one reason headlines across the political spectrum are often identical as statements, but opposite in patent intent. Making the dog whistle audible, however, doesn’t spell the “end of the ironic Nazi,” as Brian Feldman commented (Feldman 2017). It just means that the irony isn’t opposed to but instead part of the politics. Today this form of irony is enabled and constituted by digital media, and it’s not going away. It forms an irreducible part of the new political situation, one that we ignore or deny at our own peril.

Irony isn’t just intentional wit, in other words—as Quintilian already knew. One reason we nevertheless tend to confuse wit and irony is that the expansion of irony beyond the realm of rhetoric—usually dated to Romanticism, which also falls into Kantbot’s period of obsession—made irony into a category of psychology and style. Most treatments of irony take this as an assumption: modern life is drenched in the stuff, so it isn’t “just” a trope (Behler 1990). But it is a feeling, one that you get from Weird Twitter but also from the constant stream of Facebooks announcements about leaving Facebook. Quintilian already points the way beyond this gestural understanding. The problem is the source of the contradiction. It is not obvious what allows for contradiction, where it can occur, what conditions satisfy it, and thus form the basis for irony. If the source is dynamic, unstable, then the concept of irony, as Paul de Man pointed out long ago, is not really a concept at all (de Man 1996).

The theoretician of irony who most squarely accounts for its embeddedness in material and media conditions is Friedrich Schlegel. In nearly all cases, Schlegel writes, irony serves to reinforce or sharpen some message by means of the reflexivity of language: by contradicting the point, it calls it that much more vividly to mind. (Remember when Trump said, in the 2016 debates, that he refused to invoke Bill Clinton’s sexual history for Chelsea’s sake?) But there is another, more curious type:

The first and most distinguished [kind of irony] of all is coarse irony; to be found most often in the actual nature of things and which is one of its most generally distributed substances [in der wirklichen Natur der Dinge und ist einer ihrer allgemein verbreitetsten Stoffe]; it is most at home in the history of humanity (Schlegel 1958-, 368).

In other words, irony is not merely the drawing of attention to formal or material conditions of the situation of communication, but also a widely distributed “substance” or capacity in material. Twitter irony finds this substance in the platform and its underlying code, as we will see. If irony is both material and rhetorical, this means that its use is an activation of a potential in the interface between meaning and matter. This could allow, in principle, an intervention into the conditions of signification. In this sense, irony is the rhetorical term for what we could call coding, the tailoring of language to channels in technologies of transmission. Twitter reproduces an irony that built into any attempt to code language, as we are about to see. And it’s the overlap of code, irony, and politics that Kantbot marshals Hegel to address.

Coded irony—irony that is both rhetorical and digitally enabled—exploded onto the political scene in 2016 through Twitter. Twitter was the medium through which the political element of the messageboards has broken through (not least because of Trump’s nearly 60 million followers, even if nearly half of them are bots). It is far from the only politicized social medium, as a growing literature is describing (Philips and Milner, 2017; Phillips 2016; Milner 2016; Goerzen 2017). But it has been a primary site of the intimacy of media and politics over the course of 2016 and 2017, and I think that has something to do with twitter itself, and with the relationship between encoded communications and irony.

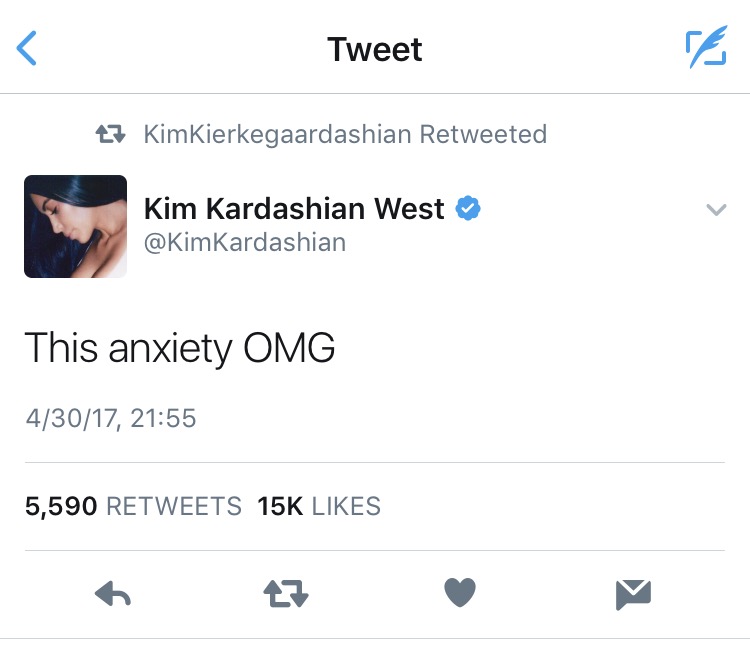

Take this retweet, which captures a great deal about Twitter:

“Kim Kierkegaardashian,” or @KimKierkegaard, joined twitter in June 2012 and has about 259,00 followers at the time of writing. The account mashes up Kardashian’s self- and brand-sales oriented tweet style with the proto-existentialism of Søren Kierkegaard. Take, for example, an early tweet from 8 July, 2012: “I have majorly fallen off my workout-eating plan! AND it’s summer! But to despair over sin is to sink deeper into it.” The account sticks close to Kardashian’s actual tweets and Kierkegaard’s actual words. In the tweet above, from April 2017, @KimKierkegaard has retweeted Kardashian herself incidentally formulating one of Kierkegaard’s central ideas in the proprietary language of social media. “Omg” as shorthand takes the already nearly entirely secular phrase “oh my god” and collapses any trace of transcendence. The retweet therefore returns us to the opposite extreme, in which anxiety points us to the finitude of human existence in Kierkegaard. If we know how to read this, it is a performance of that other Kierkegaardian bellwether, irony.

If you were to encounter Kardashian’s tweet without the retweet, there would be no irony at all. In the retweet, the tweet is presented as an object and resignified as its opposite. Note that this is a two-way street: until November 2009, there were no retweets. Before then, one had to type “RT” and then paste the original tweet in. Twitter responded, piloting a button that allows the re-presentation of a tweet (Stone 2009). This has vastly contributed to the sense of irony, since the speaker is also split between two sources, such that many accounts have some version of “RTs not endorsements” in their description. Perhaps political scandal is so often attached to RTs because the source as well as the content can be construed in multiple different and often contradictory ways. Schlegel would have noted that this is a case where irony swallows the speaker’s authority over it. That situation was forced into the code by the speech, not the other way around.

I’d like to call the retweet a resignificatory device, distinct from amplificatory. Amplificatory signaling cannibalizes a bit of redundancy in the algorithm: the more times your video has been seen on YouTube, the more likely it is to be recommended (although the story is more complicated than that). Retweets certainly amplify the original message, but they also reproduce it under another name. They have the ability to resignify—as the “repost” function on Facebook also does, to some extent.[v] Resignificatory signaling takes the unequivocal messages at the heart of the very notion of “code” and makes them rhetorical, while retaining their visual identity. Of course, no message is without an effect on its receiver—a point that information theory made long ago. But the apparent physical identity of the tweet and the retweet forces the rhetorical aspect of the message to the fore. In doing so, it draws explicit attention to the deep irony embedded in encoded messages of any kind.

Twitter was originally written in the object-oriented programming language and module-view-controller (MVC) framework Ruby on Rails, and the code matters. Object-oriented languages allow any term to be treated either as an object or as an expression, making Shannon’s observations on language operational.[vi] The retweet is an embedding of this ability to switch any term between these two basic functions. We can do this in language, of course (that’s why object-oriented languages are useful). But when the retweet is presented not as copy-pasted but as a visual reproduction of the original tweet, the expressive nature of the original tweet is made an object, imitating the capacity of the coding language. In other words, Twitter has come to incorporate the object-oriented logic of its programming language in its capacity to signify. At the level of speech, anything can be an object on Twitter—on your phone, you literally touch it and it presents itself. Most things can be resignified through one more touch, and if not they can be screencapped and retweeted (for example, the number of followers one has, a since-deleted tweet, etc.). Once something has come to signify in the medium, it can be infinitely resignified.

When, as in a retweet, an expression is made into an object of another expression, its meaning is altered. This is because its source is altered. A statement of any kind requires the notion that someone has made that statement. This means that a retweet, by making an expression into an object, exemplifies the contradiction between subject and object—the very contradiction on which Kant had based his revolutionary philosophy. Twitter is fitted, and has been throughout its existence retrofitted, to generalize this speech situation. It is the platform of the subject-object dialectic, as Hegel might have put it. By presenting subject and object in a single statement—the retweet as expression and object all at once—Twitter embodies what rhetorical theory has called irony since the ancients. It is irony as code. This irony resignifies and amplifies the rhetorical irony of the dog whistle, the troll, the President.

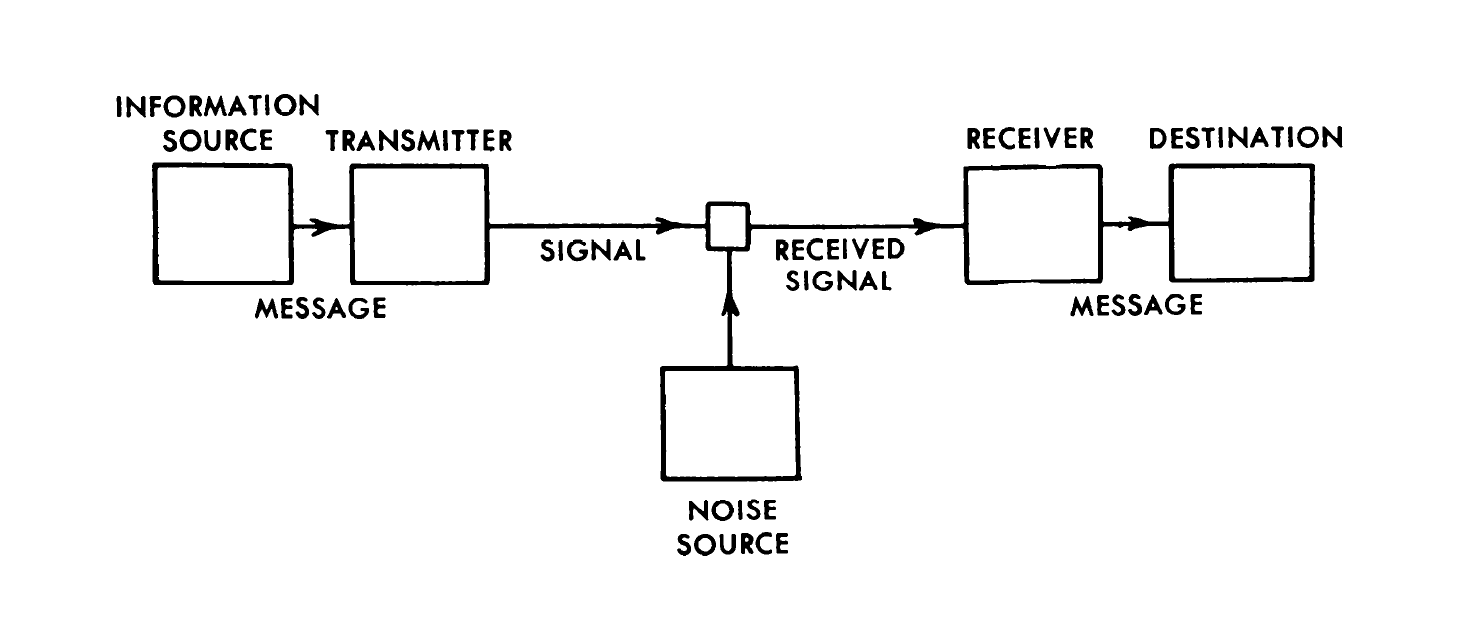

Coding is an encounter between two sets of material conditions: the structure of a language, and the capacity of a channel. This was captured in truly general form for the first time in Claude Shannon’s famous 1948 paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” in which the following diagram is given:

Shannon’s achievement was a general formula for the relation between the structure of the source and the noise in the channel.[vii] If the set of symbols can be fitted to signals complex or articulated enough to arrive through the noise, then nearly frictionless communication could be engineered. The source—his preferred example was written English—had a structure that limited its “entropy.” If you’re looking at one letter in English, for example, and you have to guess what the next one will be, you theoretically have 26 choices (including a space). But the likelihood, if the letter you’re looking at is, for example, “q,” that the next letter will be “u” is very high. The likelihood for “x” is extremely low. The higher likelihood is called “redundancy,” a limitation on the absolute measure of chaos, or entropy, that the number of elements imposes. No source for communication can be entirely random, because without patterns of one kind or another we can’t recognize what’s being communicated.[viii]

Shannon’s achievement was a general formula for the relation between the structure of the source and the noise in the channel.[vii] If the set of symbols can be fitted to signals complex or articulated enough to arrive through the noise, then nearly frictionless communication could be engineered. The source—his preferred example was written English—had a structure that limited its “entropy.” If you’re looking at one letter in English, for example, and you have to guess what the next one will be, you theoretically have 26 choices (including a space). But the likelihood, if the letter you’re looking at is, for example, “q,” that the next letter will be “u” is very high. The likelihood for “x” is extremely low. The higher likelihood is called “redundancy,” a limitation on the absolute measure of chaos, or entropy, that the number of elements imposes. No source for communication can be entirely random, because without patterns of one kind or another we can’t recognize what’s being communicated.[viii]

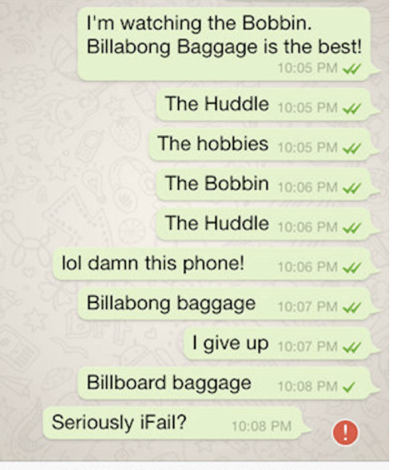

We tend to confuse entropy and the noise in the channel, and it is crucial to see that they are not the same thing. The channel is noisy, while the source is entropic. There is, of course, entropy in the channel—everything is subject to the second law of thermodynamics, without exception. But “entropy” is not in any way comparable to noise in Shannon, because “entropy” is a way of describing the conditional restraints on any structured source for communication, like the English language, the set of ideas in the brain, or what have you. Entropy is a way to describe the opposite of redundancy in the source, it expresses probability rather than the slow disintegration, the “heat death,” with which it is usually associated.[ix] If redundancy = 1, we have a kind of absolute rule or pure pattern. Redundancy works syntactically, too: “then” or “there” after the phrase “see you” is a high-level redundancy that is coded into SMS services.

This is what Shannon calls a “conditional restraint” on the theoretical absolute entropy (based on number of total parts), or freedom in choosing a message. It is also the basis for autocorrect technologies, which obviously have semantic effects, as the genre of autocorrect bloopers demonstrates.

A large portion of Shannon’s paper is taken up with calculating the redundancy of written English, which he determines to be nearly 50%, meaning that half the letters can be removed from most sentences or distorted without disturbing our ability to understand them.[x]

The general process of coding, by Shannon’s lights, is a manipulation of the relationship between the structure of the source and the capacity of the channel as a dynamic interaction between two sets of evolving rules. Shannon’s statement that the “semantic aspects” of messages were “irrelevant to the engineering problem” has often been taken to mean he played fast and loose with the concept of language (see Hayles 1999; but see also Liu 2010; and for the complex history of Shannon’s reception Floridi 2010). But rarely does anyone ask exactly what Shannon did mean, or at least conceptually sketch out, in his approach to language. It’s worth pointing to the crucial role that source-structure redundancy plays in his theory, since it cuts close to Schlegel’s notion of material irony.

Neither the source nor the channel is static. The scene of coding is open to restructuring at both ends. English is evolving; even its statistical structure changes over time. The channels, and the codes use to fit source to them, are evolving too. There is no guarantee that integrated circuits will remain the hardware of the future. They did not yet exist when Shannon published his theory.

This point can be hard to see in today’s world, where we encounter opaque packets of already-established code at every turn. It would have been less hard to see for Shannon and those who followed him, since nothing was standardized, let alone commercialized, in 1948. But no amount of stack accretion can change the fact that mediated communication rests on the dynamic relation between relative entropy in the source and the way the channel is built.

Redundancy points to this dynamic by its very nature. If there is absolute redundancy, nothing is communicated, because we already know the message with 100% certainty. With no redundancy, no message arrives at all. In between these two extremes, messages are internally objectified or doubled, but differ slightly from one another, in order to be communicable. In other words, every interpretable signal is a retweet. Redundancy, which stabilizes communicability by providing pattern, also ensures that the rules are dynamic. There is no fully redundant message. Every message is between 0 and 1, and this is what allows it to function as expression or object. Twitter imitates the rules of source structure, showing that communication is the locale where formal and material constraints encounter one another. It illustrates this principle of communication by programming it into the platform as a foundational principle. Twitter exemplifies the dynamic situation of coding as Shannon defined it. Signification is resignification.

If rhetoric is embedded this deeply into the very notion of code, then it must possess the capacity to change the situation of communication, as Schlegel suggested. But it cannot do this by fiat or by meme magic. The retweeted “this anxiety omg” hardly stands to change the statistical structure of English much. It can, however, point to the dynamic material condition of mediated signification in general, something Warren Weaver, who wrote a popularizing introduction to Shannon’s work, acknowledged:

anyone would agree that the probability is low for such a sequence of words as “Constantinople fishing nasty pink.” Incidentally, it is low, but not zero; for it is perfectly possible to think of a passage in which one sentence closes with “Constantinople fishing,” and the next begins with “Nasty pink.” And we might observe in passing that the unlikely four-word sequence under discussion has occurred in a single good English sentence, namely the one above. (Shannon and Weaver 1964, 11)

There is no further reflection in Weaver’s essay on this passage, but then, that is the nature of irony. By including the phrase “Constantinople fishing nasty pink” in the English language, Weaver has shifted its entropic structure, however slightly. This shift is marginal to our ability to communicate (I am amplifying it very slightly right now, as all speech acts do), but some shifts are larger-scale, like the introduction of a word or concept, or the rise of a system of notions that orient individuals and communities (ideology). These shifts always have the characteristic that Weaver points to here, which is that they double as expressions and objects. This doubling is a kind of generalized redundancy—or capacity for irony—built into semiotic systems, material irony flashing up into the rhetorical irony it enables. That is a Romantic notion enshrined in a founding document of the digital age.

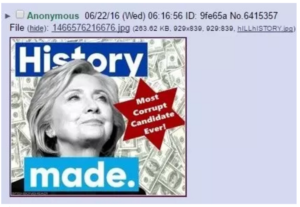

Now we can see one reason that retweeting is often the source of scandal. A retweet or repetition of content ramifies the original redundancy of the message and fragments the message’s effect. This is not to say it undermines that effect. Instead, it uses the redundancy in the source and the noise in the channel to split the message according to any one of the factors that Quintilian announced: speaker, audience, context. In the retweet, this effect is distributed across more than one of these areas, producing more than one contrary item, or internally multiple irony. Take Trump’s summer 2016 tweet of this anti-Semitic attack on Clinton—not a proper retweet, but a resignfication of the same sort:

The scandal that ensued mostly involved the source of the original content (white supremacists), and Trump skated through the incident by claiming that it wasn’t anti-Semitic anyway, it was a sheriff’s star, and that he had only “retweeted” the content. In disavowing the content in separate and seemingly contradictory ways,[xi] he signaled that he was still committed to its content to his base, while maintaining that he wasn’t at the level of statement. The effect was repeated again and again, and is a fundamental part of our government now. Trump’s positions are neither new nor interesting. What’s new is the way he amplifies his rhetorical maneuvers in social media. It is the exploitation of irony—not wit, not snark, not sarcasm—at the level of redundancy to maintain a signal that is internally split in multiple ways. This is not bad faith or stupidity; it’s an invasion of politics by irony. It’s also a kind of end to the neoliberal speech regime.

iii. Irony and Politics after 2016, or Uncommunicative Capitalism

The channel between speech and politics is open—again. That channel is saturated in irony, of a kind we are not used to thinking about. In 2003, following what were widely billed as the largest demonstrations in the history of the world, with tens of millions gathering in the streets globally to resist the George W. Bush administration’s stated intent to go to war, the United States did just that, invading Iraq on 20 March of that year. The consequences of that war have yet to be fully assessed. But while it is clear that we are living in its long foreign policy shadow, the seemingly momentous events of 2016 echo 2003 in a different way. 2016 was the year that blew open the neoliberal pax between the media, speech, and politics.

No amount of noise could prevent the invasion of Iraq. As Jodi Dean has shown, “communicative capitalism” ensured that the circulation of signs was autotelic, proliferating language and ideology sealed off from the politics of events like war or even domestic policy. She writes that:

In communicative capitalism, however, the use value of a message is less important than its exchange value, its contribution to a larger pool, flow or circulation of content. A contribution need not be understood; it need only be repeated, reproduced, forwarded. Circulation is the context, the condition for the acceptance or rejection of a contribution… Some contributions make a difference. But more significant is the system, the communicative network. (Dean 2005, 56)

This situation no longer entirely holds. Dean’s brilliant analysis—along with those of many others who diagnosed the situation of media and politics in neoliberalism (e.g. Fisher 2009; Liu 2004)—forms the basis for understanding what we are living through and in now, even as the situation has changed. The notion that the invasion of Iraq could have been stopped by the protests recalls the optimism about speech’s effect on national politics of the New Left in the 1960s and after (begging the important question of whether the parallel protests against the Vietnam War played a causal role in its end). That model of speech is no longer entirely in force. Dean’s notion of a kind of metastatic media with few if any contributions that “make a difference” politically has yielded to a concerted effort to break through that isolation, to manipulate the circulatory media to make a difference. We live with communicative capitalism, but added to it is the possibility of complex rhetorical manipulation, a political possibility that resides in the irony of the very channels that made capitalism communicative in the first place.

We know that authoritarianism engages in a kind of double-speak, talks out of “both sides of its mouth,” uses the dog whistle. It might be unusual to think of this set of techniques as irony—but I think we have to. Trump doesn’t just dog-whistle, he sends cleanly separate messages to differing effect through the same statement, as he did after Charlottesville. This technique keeps the media he is so hostile to on the hook, since their click rates are dependent on covering whatever extreme statement he’d made that day. The constant and confused coverage this led to was then a separate signal sent through the same line—by means of the contradiction between humility and vanity, and between content and effect—to his own followers. In other words, he doesn’t use Twitter only to amplify his message, but to resignify it internally. Resignificatory media allows irony to create a vector of efficacy through political discourse. That is not exactly “communicative capitalism,” but something more like the field-manipulations recently described by Johanna Drucker: affective, indirect, non-linear (Drucker 2018). Irony happens to be the tool that is not instrumental, a non-linear weapon, a kind of material-rhetorical wave one can ride but not control. As Quinn Slobodian has been arguing, we have in no way left the neoliberal era in economics. But perhaps we have left its speech regime behind. If so, that is a matter of strategic urgency for the Left.

iv. Hegelian Media Theory

The new Right is years ahead on this score, in practice but also in analysis. In one of the first pieces in what has become a truly staggering wave of coverage of the NRx movement, Rosie Gray interviewed Kantbot extensively (Gray 2017). Gray’s main target was the troll Mencius Moldbug (Curtis Yarvin) whose political philosophy blends the Enlightenment absolutism of Frederick the Great with a kind of avant-garde corporatism in which the state is run not on the model of a corporation but as a corporation. On the Alt Right, the German Enlightenment is unavoidable.

In his prose, Kantbot can be quite serious, even theoretical. He responded to Gray’s article in a Medium post with a long quotation from Schiller’s 1784 “The Theater as Moral Institution” as its epigraph (Kanbot 2017b). For Schiller, one had to imitate the literary classics to become inimitable. And he thought the best means of transmission would be the theater, with its live audience and electric atmosphere. The Enlightenment theater, as Kantbot writes, “was not only a source of entertainment, but also one of radical political education.”

Schiller argued that the stage educated more deeply than secular law or morality, that its horizon extended farther into the true vocation of the human. Culture educates where the law cannot. Schiller, it turns out, also thought that politics is downstream from culture. Kantbot finds, in other words, a source in Enlightenment literary theory for Breitbart’s signature claim. That means that narrative is crucial to political control. But Kantbot extends the point from narrative to the medium in which narrative is told.

Schiller gives us reason to think that the arrangement of the medium—its physical layout, the possibilities but also the limits of its mechanisms of transmission—is also crucial to cultural politics (this is why it makes sense to him to replace a follower’s reference to Derrida with “*schiller”). He writes that “The theater is the common channel through which the light of wisdom streams down from the thoughtful, better part of society, spreading thence in mild beams throughout the entire state.” Story needs to be embedded in a politically effective channel, and politically-minded content-producers should pay attention to the way that channel works, what it can do that another means of communication—say, the novel—can’t.

Kantbot argues that social media is the new Enlightenment Stage. When Schiller writes that the stage is the “common channel” for light and wisdom, he’s using what would later become Shannon’s term—in German, der Kanal. Schiller thought the channel of the stage was suited to tempering barbarisms (both unenlightened “savagery” and post-enlightened Terrors like Robespierre’s). For him, story in the proper medium could carry information and shape habits and tendencies, influencing politics indirectly, eventually creating an “aesthetic state.” That is the role that social media have today, according to Kantbot. In other words, the constraints of a putatively biological gender or race are secondary to their articulation through the utterly complex web of irony-saturated social media. Those media allow the categories in the first place, but are so complex as to impose their own constraint on freedom. For those on the Alt Right, accepting and overcoming that constraint is the task of the individual—even if it is often assigned mostly to non-white or non-male individuals, while white males achieve freedom through complaint. Consistency aside, however, the notion that media form their own constraint on freedom, and the tool for accepting and overcoming that constraint is irony, runs deep.

Kantbot goes on to use Schiller to critique Gray’s actual article about NRx: “Though the Altright [sic] is viewed primarily as a political movement, a concrete ideology organizing an array of extreme political positions on the issues of our time, I believe that understanding it is a cultural phenomena [sic], rather than a purely political one, can be an equally valuable way of conceptualizing it. It is here that the journos stumble, as this goes directly to what newspapers and magazines have struggled to grasp in the 21st century: the role of social media in the future of mass communication.” It is Trump’s retrofitting of social media—and now the mass media as well—to his own ends that demonstrates, and therefore completes, the system of German Idealism. Content production on social media is political because it is the locus of the interface between irony and ontology, where meme magic also resides. This allows the Alt Right to sync what we have long taken to be a liberal form of speech (irony) with extremist political commitments that seem to conflict with the very rhetorical gesture. Misogyny and racism have re-entered the public sphere. They’ve done so not in spite of but with the explicit help of ironic manipulations of media.

The trolls sync this transformation of the media with misogynist ontology. Both are construed as constraints in the forward march of Trump, Kek, and culture in general. One disturbing version of the essentialist suggestion for understanding how Trump will complete the system of German Idealism comes from one “Jef Costello” (a troll named for a character in Alain Delon’s 1967 film, Le Samouraï)

Ironically, Hegel himself gave us the formula for understanding exactly what must occur in the next stage of history. In his Philosophy of Right, Hegel spoke of freedom as “willing our determination.” That means affirming the social conditions that make the array of options we have to choose from in life possible. We don’t choose that array, indeed we are determined by those social conditions. But within those conditions we are free to choose among certain options. Really, it can’t be any other way. Hegel, however, only spoke of willing our determination by social conditions. Let us enlarge this to include biological conditions, and other sorts of factors. As Collin Cleary has written: Thus, for example, the cure for the West’s radical feminism is for the feminist to recognize that the biological conditions that make her a woman—with a woman’s mind, emotions, and drives—cannot be denied and are not an oppressive “other.” They are the parameters within which she can realize who she is and seek satisfaction in life. No one can be free of some set of parameters or other; life is about realizing ourselves and our potentials within those parameters.

As Hegel correctly saw, we are the only beings in the universe who seek self-awareness, and our history is the history of our self-realization through increased self-understanding. The next phase of history will be one in which we reject liberalism’s chimerical notion of freedom as infinite, unlimited self-determination, and seek self-realization through embracing our finitude. Like it or not, this next phase in human history is now being shepherded by Donald Trump—as unlikely a World-Historical Individual as there ever was. But there you have it. Yes! Donald Trump will complete the system of German Idealism. (Costello 2017)

Note the regular features of this interpretation: it is a nature-forward argument about social categories, universalist in application, misogynist in structure, and ultra-intellectual. Constraint is shifted not only from the social into the natural, but also back into the social again. The poststructuralist phrase “embracing our finitude” (put into the emphatic italics of Theory) underscores the reversal from semiotics to ontology by way of German Idealism. Trump, it seems, will help us realize our natural places in an old-world order even while pushing the vanguard trolls forward into the utopian future. In contrast to Kantbot’s own content, this reading lacks irony. That is not to say that the anti-Gender Studies and generally viciously misogynist agenda of the Alt Right is not being amplified throughout the globe, as we increasingly hear. But this dry analysis lack the lacks the manipulative capacity that understanding social media in German Idealist terms brings with it. It does not resignify.

Costello’s understanding is crude compared with that of Kantbot himself. The constraints, for Kantbot, are not primarily those of a naturalized gender, but instead the semiotic or rhetorical structure of the media through which any naturalization flows. The media are not likely, in this vision, to end any gender regimes—but recognizing that such regimes are contingent on representation and the manipulation of signs has never been the sole property of the Left. That manipulation implies a constrained, rather than an absolute, understanding of freedom. This constraint is an important theoretical element of the Alt Right, and in some sense they are correct to call on Hegel for it. Their thinking wavers—again, ironically—between essentialism about things like gender and race, and an understanding of constraint as primarily constituted by the media.

Kantbot mixes his andrism and his media critique seamlessly. The trolls have some of their deepest roots in internet misogyny, including so-called Men Right’s Activism and the hashtag #redpill. The red pill that Neo takes in The Matrix to exit the collective illusion is here compared to “waking up” from the “culturally Marxist” feminism that inflects the putative communism that pervades contemporary US culture. Here is Kantbot’s version:

The tweet elides any difference between corporate diversity culture and the Left feminism that would also critique it, but that is precisely the point. Irony does not undermine (it rather bolsters) serious misogyny. When Angela Nagle’s book, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right, touched off a seemingly endless Left-on-Left hot-take war, Kantbot responded with his own review of the book (since taken down). This review contains a plea for a “nuanced” understanding of Eliot Rodger, who killed six people in Southern California in 2014 as “retribution” for women rejecting him sexually.[xii] We can’t allow (justified) disgust at this kind of content to blind us to the ongoing irony—not jokes, not wit, not snark—that enables this vile ideology. In many ways, the irony that persists in the heart of this darkness allows Kantbot and his ilk to take the Left more seriously than the Left takes the Right. Gender is a crucial, but hardly the only, arena in which the Alt Right’s combination of essentialist ontology and media irony is fighting the intellectual Left.

In the sub-subculture known as Men Going Their Own Way, or MGTOW, the term “volcel” came to prominence in recent years. “Volcel” means “voluntarily celibate,” or entirely ridding one’s existence of the need for or reliance on women. The trolls responded to this term with the notion of an “incel,” someone “involuntarily celibate,” in a characteristically self-deprecating move. Again, this is irony: none of the trolls actually want to be celibate, but they claim a kind of joy in signs by recoding the ridiculous bitterness of the Volcel.

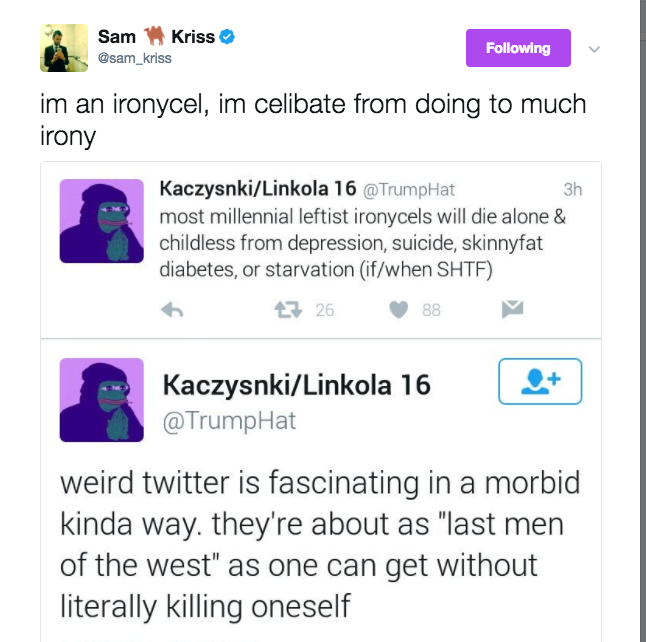

Literalizing the irony already partly present in this discourse, sometime in the fall of 2016 the trolls started calling the Left –in particular the members of the podcast team Chapo Trap House and the journalist and cultural theorist Sam Kriss (since accused of sexual harassment)—“ironycels.” The precise definition wavers, but seems to be that the Leftists are failures at irony, “irony-celibate,” even “involuntarily incapable of irony.”

Because the original phrase is split between voluntary and involuntary, this has given rise to reappropriations, for example Kriss’s, in which “doing too much irony” earns you literal celibacy.

Kantbot has commented extensively, both in articles and on podcasts, on this controversy. He and Kriss have even gone head-to-head.[xiii]

In the ironycel debate, it has become clear that Kantbot thinks that socialism has kneecapped the Left, but only sentimentally. The same goes for actual conservatism, which has prevented the Right from embracing its new counterculture. Leaving behind old ideologies is a symptom for standing at the vanguard of a civilizational shift. It is that shift that makes sense of the phrase “Trump will Complete the System of German Idealism.”

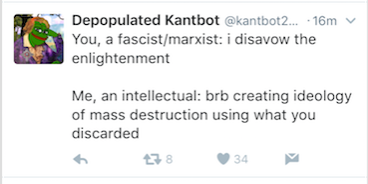

The Left, LogoDaedalus intoned on a podcast, is “metaphysically stuck in the Bush era.” I take this to mean that the Left is caught in an endless cycle of recriminations about the neoliberal model of politics, even as that model has begun to become outdated. Kantbot writes, in an article called “Chapo Traphouse Will Never Be Edgy”:

Capturing the counterculture changes nothing, it is only by the diligent and careful application of it that anything can be changed. Not politics though. When political ends are selected for aesthetic means, the mismatch spells stagnation. Counterculture, as part of culture, can only change culture, nothing outside of that realm, and the truth of culture which is to be restored and regained is not a political truth, but an aesthetic one involving the ultimate truth value of the narratives which pervade our lived social reality. Politics are always downstream. (Kantbot 2017a)

Citing Breitbart’s motto, Kantbot argues that continents of theory separate him and LogoDaedalus from the Left. That politics is downstream from culture is precisely what Marx—and by extension, the contemporary Left—could not understand. On several recent podcasts, Kantbot has made just this argument, that the German Enlightenment struck a balance between the “vitality of aesthetics” and political engagement that the Left lost in the generation after Hegel.

Kantbot has decided, against virtually every Hegel reader since Hegel and even against Hegel himself, that the system of German Idealism is ironic in its deep structure. It’s not a move we can afford to take lightly. This irony, generalized as Schlegel would have it, manipulates the formal and meta settings of communicative situations and thus is at the incipient point of any solidarity. It gathers community through mediation even as it rejects those not in the know. It sits at the membrane of the filter bubble, and—correctly used—has the potential to break or reform the bubble. To be clear, I am not saying that Kantbot has done this work. It is primarily Donald Trump, according to Kantbot’s own argument, who has done this work. But this is exactly what it means to play Hegel to Trump’s Napoleon: to provide the metaphysics for the historical moment, which happens to be the moment where social media and politics combine. Philosophy begins only after an early-morning sleepless tweetstorm once again determines a news cycle. Irony takes its proper place, as Schlegel had suggested, in human history, becoming a political weapon meant to manipulate communication.

Kantbot was the media theorist of Trump’s ironic moment. The channeling of affect is irreducible, but not unchangeable: this is both the result of some steps we can only wish we’d taken in theory and used in politics before the Alt Right got there, and the actual core of what we might call Alt Right Media Theory. When they say “the Left can’t meme,” in other words, they’re accusing the socialist Left of being anti-intellectual about the way we communicate now, about the conditions and possibilities of social media’s amplifications of the capacity called irony that is baked in to cognition and speech so deeply that we can barely define it even partially. That would match the sense of medium we get from looking at Shannon again, and the raw material possibility with which Schlegel infused the notion of irony.

This insight, along with its political activation, might have been the preserve of Western Marxism or the other critical theories that succeeded it. Why have we allowed the Alt Right to pick up our tools?

Kantbot takes obvious pleasure in the irony of using poststructuralist tools, and claiming in a contrarian way that they really derive from a broadly construed German Enlightenment that includes Romanticism and Idealism. Irony constitutes both that Enlightenment itself, on this reading, and the attitude towards it on the part of the content-producers, the German Idealist Trolls. It doesn’t matter if Breitbart was right about the Frankfurt School, or if the Neoreactionaries are right about capitalism. They are not practicing what Hegel called “representational thinking,” in which the goal is to capture a picture of the world that is adequate to it. They are practicing a form of conceptual thinking, which in Hegel’s terms is that thought that is embedded in, constituted by, and substantially active within the causal chain of substance, expression, and history.[xiv] That is the irony of Hegel’s reincarnation after the end of history.

In media analysis and rhetorical analysis, we often hear the word “materiality” used as a substitute for durability, something that is not easy to manipulate. What is material, it is implied, is a stabilizing factor that allows us to understand the field of play in which signification occurs. Dean’s analysis of the Iraq War does just this, showing the relationship of signs and politics that undermines the aspirational content of political speech in neoliberalism. It is a crucial move, and Dean’s analysis remains deeply informative. But its type—and even the word “material,” used in this sense—is, not to put too fine a point on it, neo-Kantian: it seeks conditions and forms that undergird spectra of possibility. To this the Alt Right has lodged a Hegelian eppur si muove, borrowing techniques that were developed by Marxists and poststructuralists and German Idealists, and remaking the world of mediated discourse. That is a political emergency in which the humanities have a special role to play—but only if we can dispense with political and academic in-fighting and turn our focus to our opponents. What Mark Fisher once called the “Vampire castle” of the Left on social media is its own kind of constraint on our progress (Fisher 2013). One solvent for it is irony in the expanded field of social media—not jokes, not snark, but dedicated theoretical investigation and exploitation of the rhetorical features of our systems of communication. The situation of mediated communication is part of the objective conjuncture of the present, one that the humanities and the Left cannot afford to ignore, and cannot avoid by claiming not to participate. The alternative to engagement is to cede the understanding, and quite possibly the curve, of civilization, to the global Alt Right.

_____

Leif Weatherby is Associate Professor of German and founder of the Digital Theory Lab at NYU. He is working on a book about cybernetics and German Idealism.

_____

Notes

[i] Video here. The comment thread on the video generated a series of unlikely slogans for 2020: “MAKE TRANSCENDENTAL IDENTITY GREAT AGAIN,” “Make German Idealism real again,” and the ideological non sequitur “Make dialectical materialism great again.”

[ii] Neiwert (2017) tracks the rise of extreme Right violence and media dissemination from the 1990s to the present, and is particularly good on the ways in which these movements engage in complex “double-talk” and meta-signaling techniques, including irony in the case of the Pepe meme.

[iii] I’m going to use this term throughout, and refer readers to Chip Berlet’s useful resource: I’m hoping this article builds on a kind of loose consensus that the Alt Right “talks out of both sides of its mouth,” perhaps best crystallized in the term “dog whistle.” Since 2016, we’ve seen a lot of regular whistling, bigotry without disguise, alongside the rise of the type of irony I’m analyzing here.

[iv] There is, in this wing of the Online Right, a self-styled “autism” that stands for being misunderstood and isolated.

[v] Thanks to Moira Weigel for a productive exchange on this point.

[vi] See the excellent critique of object-oriented ontologies on the basis of their similarities with object-oriented programming languages in Galloway 2013. Irony is precisely the condition that does not reproduce code representationally, but instead shares a crucial condition with it.

[vii] The paper is a point of inspiration and constant return for Friedrich Kittler, who uses this diagram to demonstrate the dependence of culture on media, which, as his famous quip goes, “determine our situation.” Kittler 1999, xxxix.

[viii] This kind of redundancy is conceptually separate from signal redundancy, like the strengthening or reduplicating of electrical impulses in telegraph wires. The latter redundancy is likely the first that comes to mind, but it is not the only kind Shannon theorized.

[ix] This is because Shannon adopts Ludwig Boltzmann’s probabilistic formula for entropy. The formula certainly suggests the slow simplification of material structure, but this is irrelevant to the communications engineering problem, which exists only so long as there are the very complex structures called humans and their languages and communications technologies.

[x] Shannon presented these findings at one of the later Macy Conferences, the symposia that founded the movement called “cybernetics.” For an excellent account of what Shannon called “Printed English,” see Liu 2010, 39-99.

[xi] The disavowal follows Freud’s famous “kettle logic” fairly precisely. In describing disavowal of unconscious drives unacceptable to the ego and its censor, Freud used the example of a friend who returns a borrowed kettle broken, and goes on to claim that 1) it was undamaged when he returned it, 2) it was already damaged when he borrowed it, and 3) he never borrowed it in the first place. Zizek often uses this logic to analyze political events, as in Zizek 2005. Its ironic structure usually goes unremarked.

[xii] Kantbot, “Angela Nagle’s Wild Ride,” http://thermidormag.com/angela-nagles-wild-ride/, visited August 15, 2017—link currently broken.

[xiii] Kantbot does in fact write fiction, almost all of which is science-fiction-adjacent retoolings of narrative from German Classicism and Romanticism. The best example is his reworking of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “A New Year’s Eve Adventure,” “Chic Necromancy,” Kantbot 2017c.

[xiv] I have not yet seen a use of Louis Althusser’s distinction between representation and “theory” (which relies on Hegel’s distinction) on the Alt Right, but it matches their practice quite precisely.

_____

Works Cited

- Beckett, Andy. 2017. “Accelerationism: How a Fringe Philosophy Predicted the Future We Live In.” The Guardian (May 11).

- Behler, Ernst. 1990. Irony and the Discourse of Modernity. Seattle: University of Washington.

- Berkowitz, Bill. 2003. “ ‘Cultural Marxism’ Catching On.” Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Breitbart, Andrew. 2011. Righteous Indignation: Excuse Me While I Save the World! New York: Hachette.

- Burton, Tara. 2016. “Apocalypse Whatever: The Making of a Racist, Sexist Religion of Nihilism on 4chan.” Real Life Mag (Dec 13).

- Costello, Jef. 2017. “Trump Will Complete the System of German Idealism!” Counter-Currents Publishing (Mar 10).

- de Man, Paul. 1996. “The Concept of Irony.” In de Man, Aesthetic Ideology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. 163-185.

- Dean, Jodi. 2005. “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics.” Cultural Politics 1:1. 51-74.

- Drucker, Johanna. The General Theory of Social Relativity. Vancouver: The Elephants.

- Feldman, Brian. 2017. “The ‘Ironic’ Nazi is Coming to an End.” New York Magazine.

- Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? London: Zer0.

- Fisher, Mark. 2013. “Exiting the Vampire Castle.” Open Democracy (Nov 24).

- Floridi, Luciano. 2010. Information: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford.

- Galloway, Alexander. 2013. “The Poverty of Philosophy: Realism and Post-Fordism.” Critical Inquiry 39:2. 347-66.

- Goerzen, Matt. 2017. “Notes Towards the Memes of Production.” texte zur kunst (Jun).

- Gray, Rosie. 2017. “Behind the Internet’s Dark Anti-Democracy Movement.” The Atlantic (Feb 10).

- Haider, Shuja. 2017. “The Darkness at the End of the Tunnel: Artificial Intelligence and Neorreaction.” Viewpoint Magazine.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Higgins, Richard. 2017. “POTUS and Political Warfare.” National Security Council Memo.

- Huyssen, Andreas. 2017. “Breitbart, Bannon, Trump, and the Frankfurt School.” Public Seminar (Sep 28).

- Jay, Martin. 2011. “Dialectic of Counter-Enlightenment: The Frankfurt School as Scapegoat of the Lunatic Fringe.” Salmagundi 168/169 (Fall 2010-Winter 2011). 30-40. Excerpt at Canisa.Org.

- Kantbot (as Edward Waverly). 2017a. “Chapo Traphouse Will Never Be Edgy”

- Kantbot. 2017b. “All the Techcomm Blogger’s Men.” Medium.

- Kantbot. 2017c. “Chic Necromancy.” Medium.

- Kittler, Friedrich. 1999. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Liu, Alan. 2004. “Transcendental Data: Toward a Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded Discourse.” Critical Inquiry 31:1. 49-84.

- Liu, Lydia. 2010. The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Marwick, Alice and Rebecca Lewis. 2017. “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.” Data & Society.

- Milner, Ryan. 2016. The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. Cambridge: MIT.

- Neiwert, David. 2017. Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump. New York: Verso.

- Noys, Benjamin. 2014. Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism. London: Zer0.

- Phillips, Whitney and Ryan M. Milner. 2017. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Cambridge: Polity.

- Phillips, Whitney. 2016. This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Quintilian. 1920. Institutio Oratoria, Book VIII, section 6, 53-55.

- Schlegel, Friedrich. 1958–. Kritische Friedrich-Schlegel-Ausgabe. Vol. II. Edited by Ernst Behler, Jean Jacques Anstett, and Hans Eichner. Munich: Schöningh.

- Shannon, Claude, and Warren Weaver. 1964. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Stone, Biz. 2009. “Retweet Limited Rollout.” Press release. Twitter (Nov 6).

- Walsh, Michael. 2017. The Devil’s Pleasure Palace: The Cult of Critical Theory and the Subversion of the West. New York: Encounter Books.

- Winter, Jana and Elias Groll. 2017. “Here’s the Memo that Blew Up the NSC.” Foreign Policy (Aug 10).

- Žižek, Slavoj. 1993. Tarrying with the Negative: Kant, Hegel and the Critique of Ideology. Durham: Duke, 1993.

- Žižek, Slavoj. 2005. Iraq: The Borrowed Kettle. New York: Verso.