Millions of the sex whose names were never known beyond the circles of their own home influences have been as worthy of commendation as those here commemorated. Stars are never seen either through the dense cloud or bright sunshine; but when daylight is withdrawn from a clear sky they tremble forth. (Hale 1853, ix)

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor, reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of reference so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” so often seems to exclude women. This essay takes on one of the “tests” used to determine whether content is worthy of inclusion in Wikipedia, notability, to explore how the purportedly neutral concept works against efforts to create entries about female historical figures.

According to Wikipedia “notability,” a subject is considered notable if it “has received significant coverage in reliable sources that are independent of the subject.” (“Wikipedia:Notability” 2017) To a historian of women, the gender biases implicit in these criteria are immediately recognizable; for most of written history, women were de facto considered unworthy of consideration (Smith 2000). Unsurprisingly, studies have pointed to varying degrees of bias in coverage of female figures in Wikipedia compared to male figures. One study of Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia concluded,

Overall, we find evidence of gender bias in Wikipedia coverage of biographies. While Wikipedia’s massive reach in coverage means one is more likely to find a biography of a woman there than in Britannica, evidence of gender bias surfaces from a deeper analysis of those articles each reference work misses. (Reagle and Rhue 2011)

Five years later, another study found this bias persisted; women constituted only 15.5 percent of the biographical entries on the English Wikipedia, and that for women born prior to the 20th century, the problem of exclusion was wildly exacerbated by “sourcing and notability issues” (“Gender Bias on Wikipedia” 2017).

One potential source for buttressing the case of notable women has been identified by literary scholar Alison Booth. Booth identified more than 900 volumes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular (Booth 2004). Booth also points out that, lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood” (Booth 2004, 3).

To reveal the historical contingency of the purportedly neutral criteria of notability, I utilized longitudinal data compiled by Booth which reveals that notability has never been the stable concept Wikipedia’s standards take it to be. Since notability alone cannot explain which women make it into Wikipedia, I then turn to a methodology first put forth by historian Mary Ritter Beard in her critique of the Encyclopedia Britannica to identify missing entries (Beard 1977). Utilizing Notable American Women, as a reference corpus, I calculated the inclusion of individual women from those volumes in Wikipedia (Boyer and James 1971). In this essay I extend that analysis to consider the difference between notability and notoriety from a historical perspective. One might be well known while remaining relatively unimportant from a historical perspective. Such distinctions are collapsed in Wikipedia, assuming that a body of writing about a historical subject stands as prima facie evidence of notability.

While inclusion in Notable American Women does not necessarily translate into presence in Wikipedia, looking at the categories of women that have higher rates of inclusion offers insights into how female historical figures do succeed in Wikipedia. My analysis suggests that criterion of notability restricts the women who succeed in obtaining pages in Wikipedia to those who mirror “the ‘Great Man Theory’ of history (Mattern 2015) or are “notorious” (Lerner 1975).

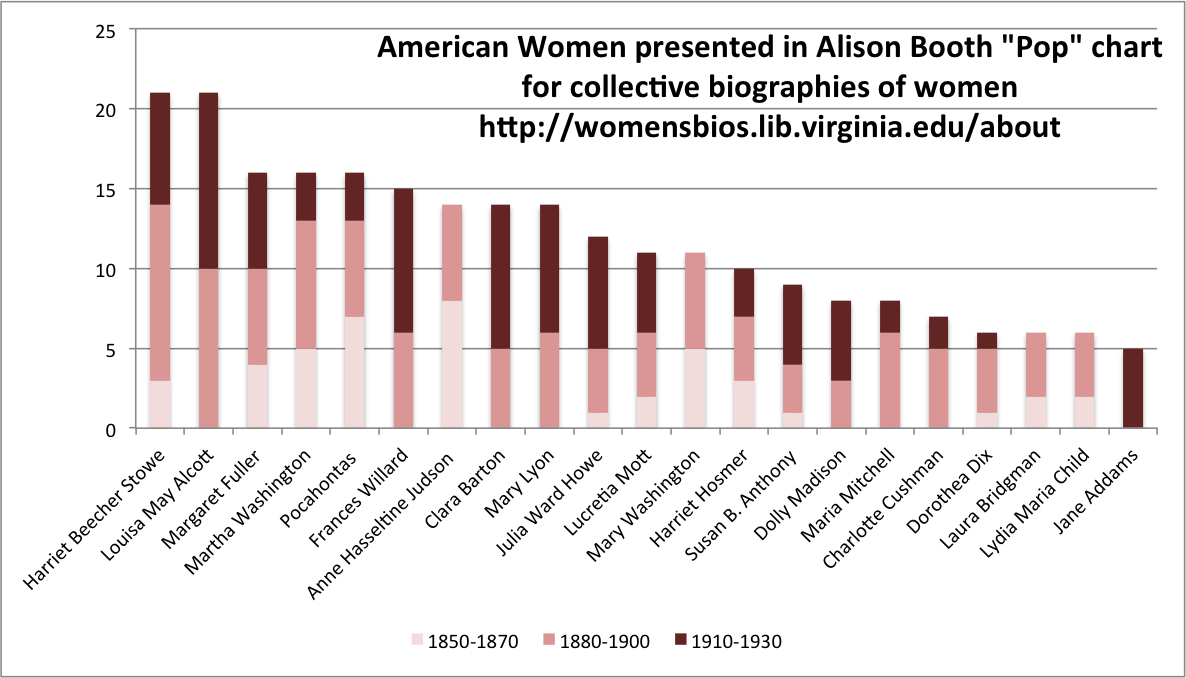

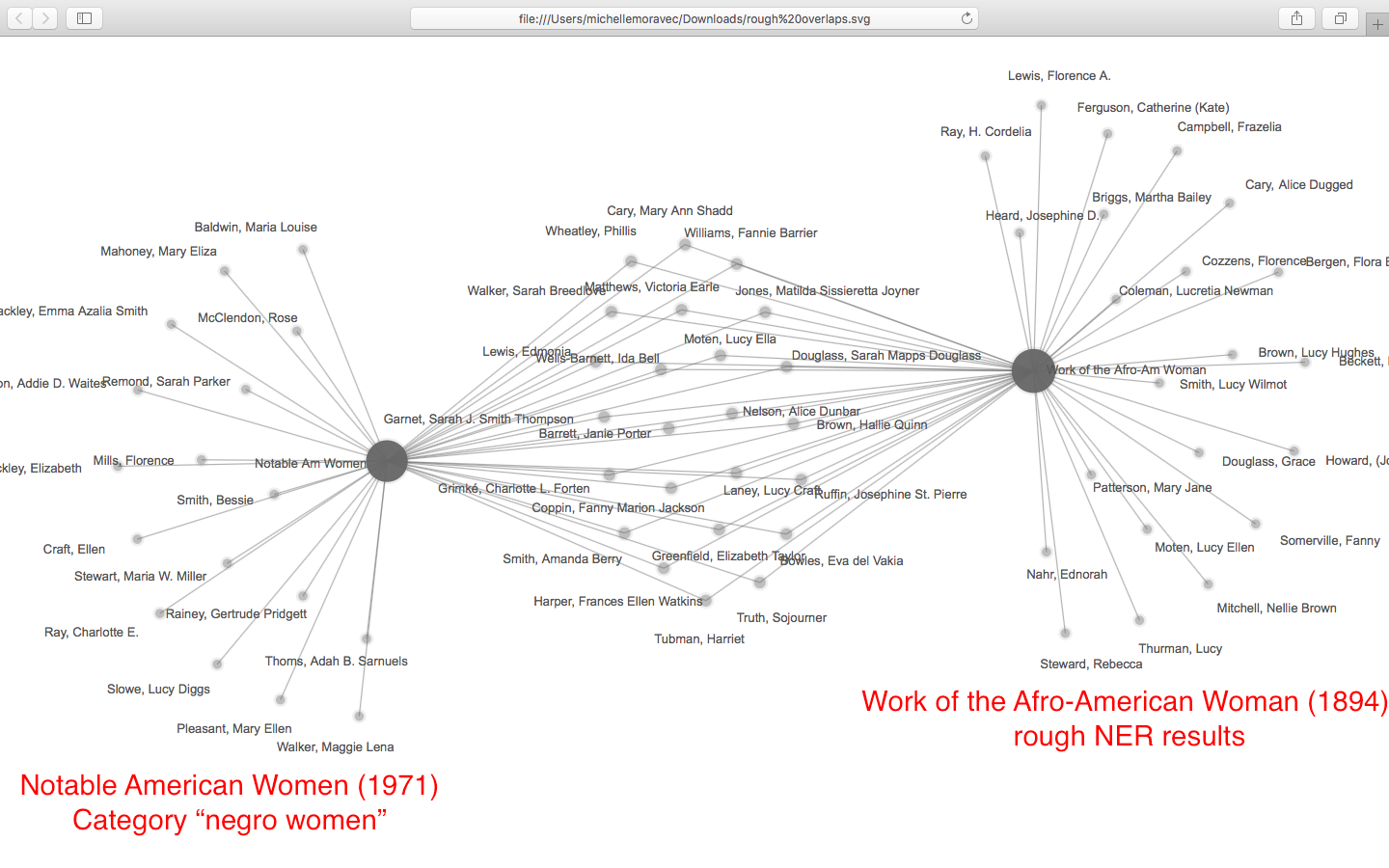

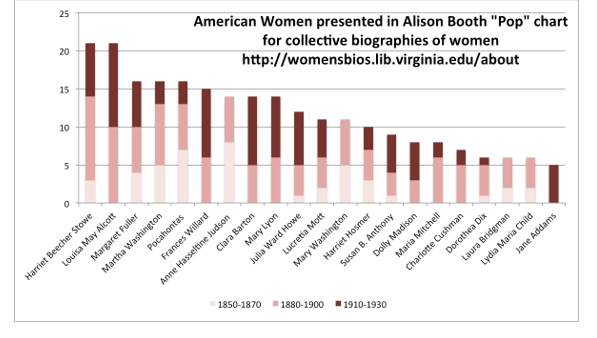

Alison Booth has compiled a list of the most frequently mentioned women in a subset of female prosopographical volumes and tracked their frequency over time (2004, 394–396). She made this data available on the web, allowing for the creation of Figure 1 which focuses on the inclusion of US historical figures in volumes published from 1850 to 1930.

This chart clarifies what historians already know: notability is historically specific and contingent. For example, Mary Washington, mother of the first president, is notable in the nineteenth century but not in the twentieth. She drops off because over time, motherhood alone ceases to be seen as a significant contribution to history. Wives of presidents remain quite popular, perhaps because they were at times understood as playing an important political role, so Mary Washington’s daughter-in-law Martha still appears in some volumes in the latter period. A similar pattern may be observed for foreign missionary Anne Hasseltine Judson in the twentieth century. The novelty of female foreign missionaries like Judson faded as more women entered the field. Other figures, like Laura Bridgman, “the first deaf-blind American child to gain a significant education in the English language,” were supplanted by later figures in what might be described as the “one and done” syndrome, where only a single spot is allotted for a specific kind of notable woman (“Laura Bridgman” 2017). In this case, Bridgman likely fell out of favor as Helen Keller’s fame rose.

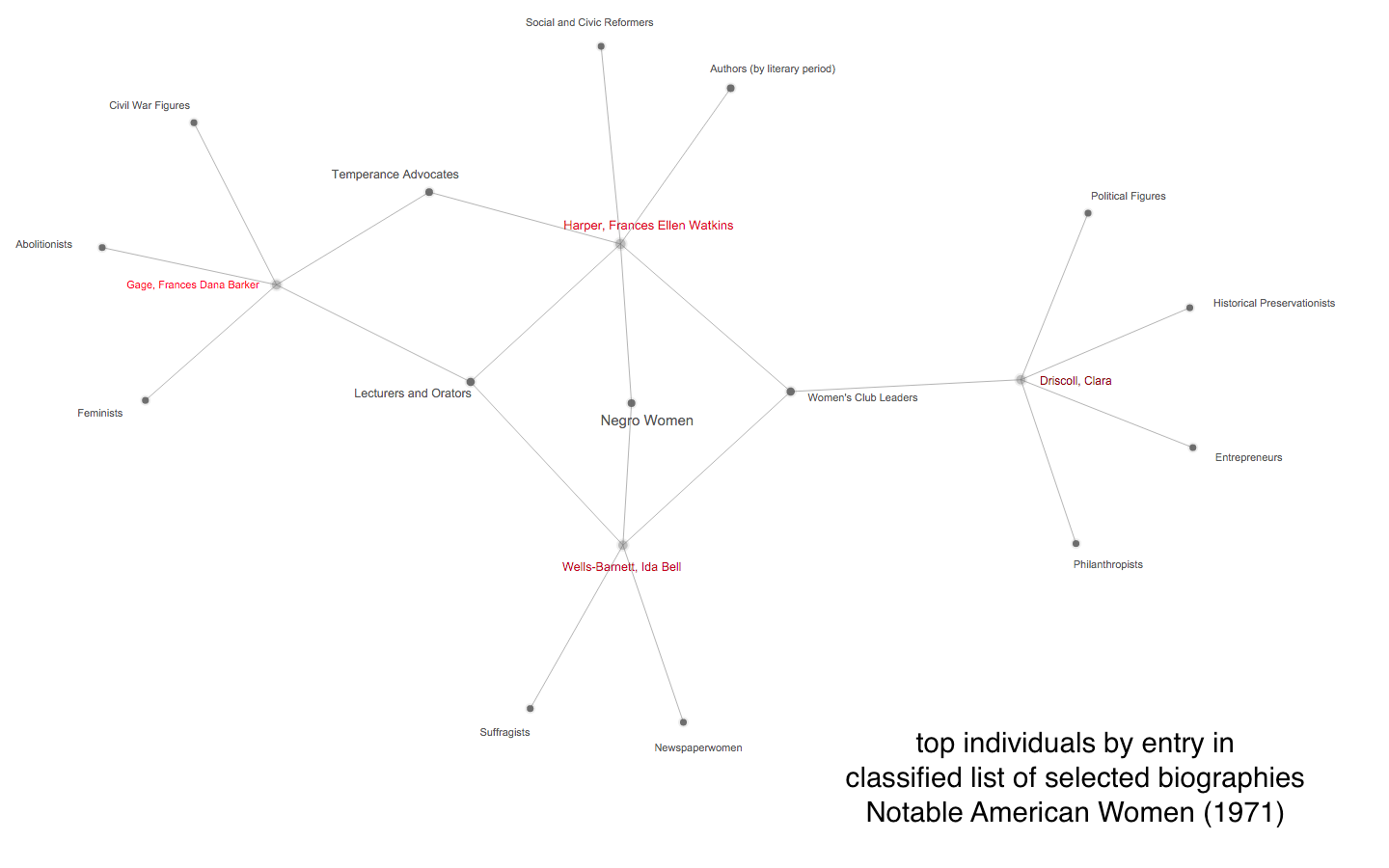

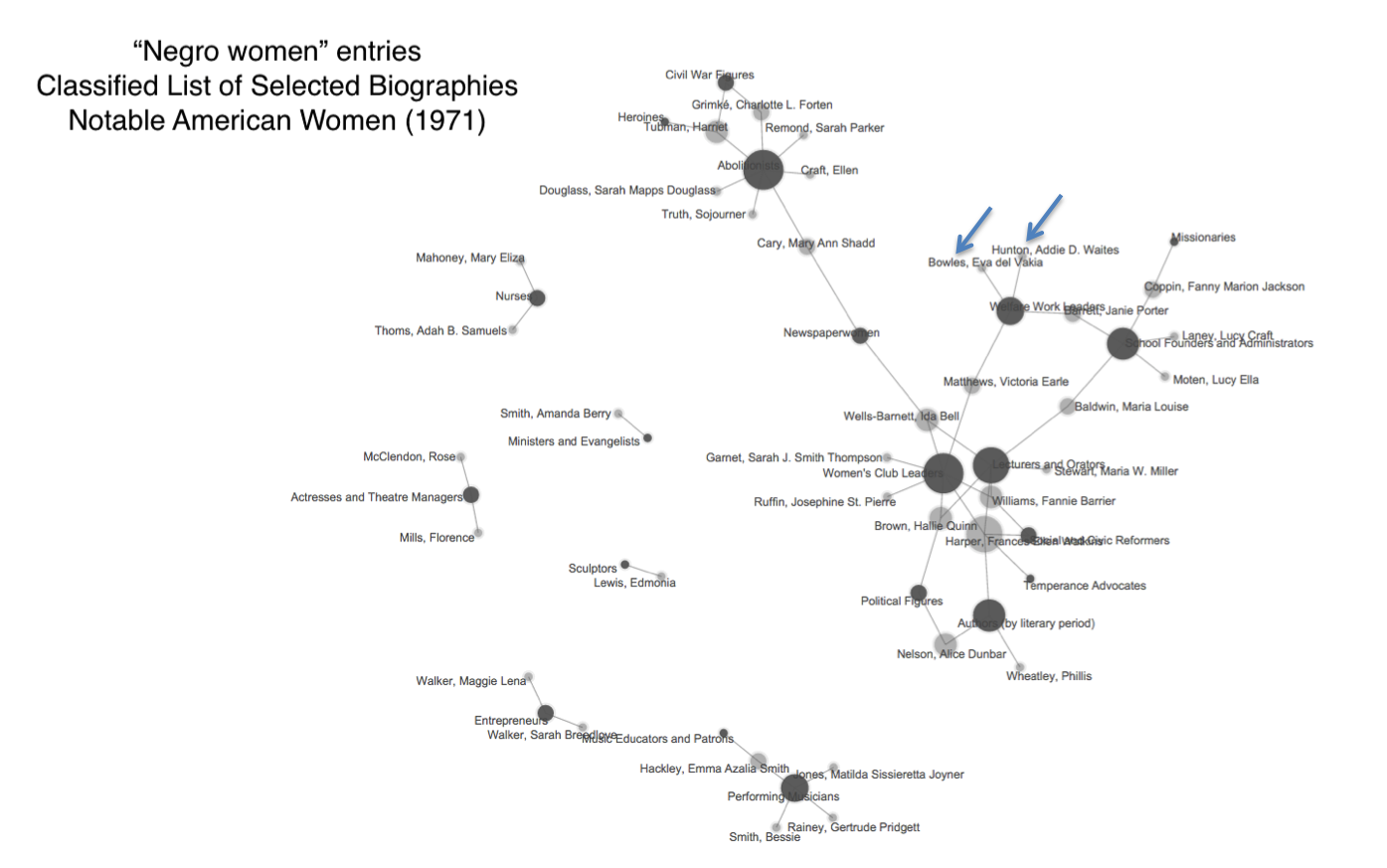

Although their notability changed over time, all the women depicted in figure 1 have Wikipedia pages; this is unsurprising as they were among the most mentioned women in the sort of volumes Wikipedia considers “reliable sources.” But what about more contemporary examples? Does inclusion in a relatively recent work that declares women as notable mean that these women would meet Wikipedia’s notability standards? To answer this question, I relied on a methodology of calculating missing biographies in Wikipedia, utilizing a reference corpus to identify women who might reasonably be expected to appear in Wikipedia and to calculate the percentage that do not. Working with the digitized copy of Notable American Women in the Women and Social Movements database, I compiled a missing biographies quotient for individuals in selected sections of the “classified list of biographies” that appear at the end of the third volume of Notable American Women. The eleven categories with no missing entries offer some insights into how women do succeed in Wikipedia (Table 1).

| Classification | % missing |

| Astronomers | 0 |

| Biologists | 0 |

| Chemists & Physicists | 0 |

| Heroines | 0 |

| Illustrators | 0 |

| Indian Captives | 0 |

| Naturalists | 0 |

| Psychologists | 0 |

| Sculptors | 0 |

| Wives of Presidents | 0 |

Table 1. Classifications from Notable American Women with no missing biographies in Wikipedia

Characteristics that are highly predictive of success in Wikipedia for women include association with a powerful man, as in the wives of presidents, and recognition in a male-dominated field of science, social science and art. Additionally, extraordinary women, such as heroines, and those who are quite rare, such as Indian captives, also have a greater chance of success in Wikipedia.[1]

Further analysis of the classifications with greater proportions of missing women reflects Gerda Lerner’s complaint that the history of notable women is the story of exceptional or deviant women (Lerner 1975). “Social worker,” which has the highest percentage of missing biographies at 67%, illustrates that individuals associated with female-dominated endeavors are less likely to be considered notable unless they rise to a level of exceptionalism (Table 2).

| Name | Included? |

| Dinwiddie, Emily Wayland |

no |

| Glenn, Mary Willcox Brown |

no |

| Kingsbury, Susan Myra |

no |

| Lothrop, Alice Louise Higgins |

no |

| Pratt, Anna Beach |

no |

| Regan, Agnes Gertrude |

no |

| Breckinridge, Sophonisba Preston |

page |

| Richmond, Mary Ellen |

page |

| Smith, Zilpha Drew |

stub |

Table 2. Social Workers from Notable American Women by inclusion in Wikipedia

Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge’s Wikipedia entry describes her as “an American activist, Progressive Era social reformer, social scientist and innovator in higher education” who was also “the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in political science and economics then the J.D. at the University of Chicago, and she was the first woman to pass the Kentucky bar” (“Sophonisba Breckinridge” 2017). While the page points out that “She led the process of creating the academic professional discipline and degree for social work,” her page is not linked to the category of American social workers (“Category:American Social Workers” 2015). If a female historical figure isn’t as exceptional as Breckinridge, she needs to be a “first” like Mary Ellen Richmond who makes it into Wikipedia as the “social work pioneer” (“Mary Richmond” 2017).

This conclusion that being a “first” facilitates success in Wikipedia is supported by analysis of the classification of nurses. Of the ten nurses who have Wikipedia entries, 80% are credited with some sort of temporally marked achievement, generally a first or pioneering role (Table 3).

| Individual | Was she a first? | Was she a participant in a male-dominated historical event? | Was she a founder? |

| Delano, Jane Arminda | leading pioneer | World War I | founder of the American Red Cross Nursing Service |

| Fedde, Sister Elizabeth* | established the Norwegian Relief Society | ||

| Maxwell, Anna Caroline | pioneering activities | Spanish-American War | |

| Nutting, Mary Adelaide | world’s first professor of nursing | World War I | founded the American Society of superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses |

| Richards, Linda | first professionally trained American nurse, pioneering modern nursing in the United States | No | Richards pioneered the founding and superintending of nursing training schools across the nation. |

| Robb, Isabel Adams Hampton | early leader (held many “first” positions) | No | helped to found …the National League for Nursing, the International Council of Nurses, and the American Nurses Association. |

| Stimson, Julia Catherine | first woman to attain the rank of Major | World War I | |

| Wald, Lillian D. | coined the term “public health nurse” & the founder of American community nursing | No | founded Henry Street Settlement |

| Mahoney, Mary Eliza | first African American to study and work as a professionally trained nurse in the US | No | co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses |

| Thoms, Adah B. Samuels | World War I | co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses |

* Fredde appears in Wikipedia primarily as a Norwegian Lutheran Deaconess. The word “nurse” does not appear on her page.

Table 3. Classifications from Notable American Women with no missing biographies in Wikipedia

As the entries for nurses reveal, in addition to being first, a combination of several additional factors work in a female subject’s favor in achieving success in Wikipedia. Nurses who founded an institution or organization or participated in a male-dominated event already recognized as historically significant, such as war, were more successful than those who did not.

If distinguishing oneself, by being “first” or founding something, as part of a male-dominated event facilitates higher levels of inclusion in Wikipedia for women in female dominated fields, do these factors also explain how women from classifications that are not female-dominated succeed? Looking at labor leaders, it appears these factors can offer only a partial explanation (Table 4).

| Individual | Was she a first? | Was she a participant in a male-dominated historical event? | Was she a founder? | Description from Wikipedia |

| Bagley, Sarah G. | “probably the first” | No | formed the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association | headed up female department of newspaper until fired because “a female department. … would conflict with the opinions of the mushroom aristocracy … and beside it would not be dignified” |

| Barry, Leonora Marie Kearney | “only woman” “first woman” | KNIGHTS OF LABOR | “difficulties faced by a woman attempting to organize men in a male-dominated society. Employers also refused to allow her to investigate their factories.” |

|

| Bellanca, Dorothy Jacobs | “first full-time female organizer” | No | 0rganized the Baltimore buttonhole makers into Local 170 of the United Garment Workers of America, one of four women who attended founding convention of Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America | “ “men resented” her |

| Haley, Margaret Angela | “pioneer leader” | No | No | dubbed the “lady labor slugger” |

| Jones, Mary Harris | No | KNIGHTS OF LABOR | IWW | “most dangerous woman in America” |

| Nestor, Agnes | No | WOMEN’S TRADE UNION LEAGUE | founded International Glove Workers Union | |

| O’Reilly, Leonora | No | WOMEN’S TRADE UNION LEAGUE | founded the Wage Earners Suffrage League | “O’Reilly as a public speaker was thought to be out of place for women at this time in New York’s history.” |

| O’Sullivan, Mary Kenney | the first woman AFL employed | WOMEN’S TRADE UNION LEAGUE | founder of the Women’s Trade Union League | |

| Stevens, Alzina Parsons | first probation officer | KNIGHTS OF LABOR |

Table 4. Classifications from Notable American Women with no missing biographies in Wikipedia

In addition to being a “first” or founding something, two other variables emerge from the analysis of labor leaders that predict success in Wikipedia. One is quite heartening: affiliation with the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), a significant female-dominated historical organization, seems to translate into greater recognition as historically notable. Less optimistically, it also appears that what Lerner labeled as “notorious” behavior predicts success: six of the nine women were included for a wide range of reasons, from speaking out publicly to advocating resistance.

The conclusions here can be spun two ways. If we want to get women into Wikipedia, to surmount the obstacle of notability, we should write about women who fit well within the great man school of history. This could be reinforced within the architecture of Wikipedia by creating links within a woman’s entry to men and significant historical events, while also making sure that the entry emphasizes a woman’s “firsts” and her institutional ties. Following these practices will make an entry more likely to overcome challenges and provide a defense against proposed deletion. On the other hand, these are narrow criteria for meeting notability that will likely not encompass a wide range of female figures from the past.

The larger question remains: should we bother to work in Wikipedia at all? (Raval 2014). Wikipedia’s content is biased not only by gender, but also by race and region (“Racial Bias on Wikipedia” 2017). A concrete example of this intersectional bias can be seen if the fact that “only nine of Haiti’s 37 first ladies have Wikipedia articles, whereas all 45 first ladies of the United States have entries” (Frisella 2017). Critics have also pointed to the devaluation of Indigenous forms of knowledge within Wikipedia (Senier 2014; Gallart and van der Velden 2015).

Wikipedia, billed as “the encyclopedia anyone can edit” and purporting to offer “the sum of all human knowledge,” is notorious for achieving neither goal. Wikipedia’s content suffers from systemic bias related to the unbalanced demographics of its contributor base (Wikipedia, 2004, 2009c). I have highlighted here disparities in gendered content, which parallel the well-documented gender biases against female contributors (“Wikipedia:WikiProject Countering Systemic Bias” 2017). The average editor of Wikipedia is white, from Western Europe or the United States, between 30-40, and overwhelmingly male. Furthermore, “super users” contribute most of Wikipedia’s content. A 2014 analysis revealed that “the top 5,000 article creators on English Wikipedia have created 60% of all articles on the project. The top 1,000 article creators account for 42% of all Wikipedia articles alone.” A study of a small sample of these super users revealed that they are not writing about women. “The amount of these super page creators only exacerbates the [gender] problem, as it means that the users who are mass-creating pages are probably not doing neglected topics, and this tilts our coverage disproportionately towards male-oriented topics” (Hale 2014). For example, the “List of Pornographic Actresses” on Wikipedia is lengthier and more actively edited than the “List of Female Poets” (Kleeman 2015).

The hostility within Wikipedia against female contributors remains a significant barrier to altering its content since the major mechanism for rectifying the lack of entries about women is to encourage women to contribute them (New York Times 2011; Peake 2015; Paling 2015). Despite years of concerted efforts to make Wikipedia more hospitable toward women, to organize editathons, and place Wikipedians in residencies specifically designed to add women to the online encyclopedia, the results have been disappointing (MacAulay and Visser 2016; Khan 2016). Authors of a recent study of “Wikipedia’s infrastructure and the gender gap” point to “foundational epistemologies that exclude women, in addition to other groups of knowers whose knowledge does not accord with the standards and models established through this infrastructure” which includes “hidden layers of gendering at the levels of code, policy and logics” (Wajcman and Ford 2017).

Among these policies is the way notability is implemented to determine whether content is worthy of inclusion. The issues I raise here are not new; Adrianne Wadewitz, an early and influential feminist Wikipedian, noted in 2013 “A lack of diversity amongst editors means that, for example, topics typically associated with femininity are underrepresented and often actively deleted”(Wadewitz 2013). Wadewitz pointed to efforts to delete articles about Kate Middleton’s wedding gown, as well as the speedy nomination for deletion of an entry for reproductive rights activist Sandra Fluke. Both pages survived, Wadewicz emphasized, reflecting the way in which Wikipedia guidelines develop through practice, despite their ostensible stability.

This is important to remember – Wikipedia’s policies, like everything on the site, evolves and changes as the community changes. … There is nothing more essential than seeing that these policies on Wikipedia are evolving and that if we as feminists and academics want them to evolve in ways we feel reflect the progressive politics important to us, we must participate in the conversation. Wikipedia is a community and we have to join it. (Wadewitz 2013)

While I have offered some pragmatic suggestions here about how to surmount the notability criteria in Wikipedia, I want to close by echoing Wadewitz’s sentiment that the greater challenge must be to question how notability is implemented in Wikipedia praxis.

_____

Michelle Moravec is an associate professor of history at Rosemont College.

_____

Notes

[1] Seven of the eleven categories in my study with fewer than ten individuals have no missing individuals.

_____

Works Cited

- Beard, Mary Ritter. 1977. “A Study of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in Relation to Its Treatment of Women.” In Ann J. Lane, ed., Making Women’s History: The Essential Mary Ritter Beard. Feminist Press at CUNY. 215–24.

- Booth, Alison. 2004. How to Make It as a Woman: Collective Biographical History from Victoria to the Present. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press.

- Boyer, Paul, and Janet Wilson James, eds. 1971. Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary. III vols. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- “Category:American Social Workers.” 2015. Wikipedia.

- Frisella, Emily. 2017. “How Activists Are Diversifying Wikipedia One Edit At A Time.” GOOD Magazine (Apr 27).

- Gallart, Peter, and Maja van der Velden. 2015. “The Sum of All Human Knowledge? Wikipedia and Indigenous Knowledge.” In Nicola Bidwell and Heike Winschiers-Theophilus, eds., At the Intersection of Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge and Technology Design. Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press. 117–34

- “Gender Bias on Wikipedia.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- Hale, Sarah Josepha Buell. 1853. Woman’s Record: Or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from “the Beginning” Till A.D. 1850. Arranged in Four Eras. With Selections from Female Writers of Every Age. Harper & Brothers.

- Khan, Aysha. 2016. “The Slow and Steady Battle to Close Wikipedia’s Dangerous Gender Gap.” Think Progress (Dec 15).

- Kleeman, Jenny. 2015. “The Wikipedia Wars: Does It Matter If Our Biggest Source of Knowledge Is Written by Men?” New Statesman (May 26).

- “Laura Bridgman.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- Lerner, Gerda. 1975. “Placing Women in History: Definitions and Challenges. Author.” Feminist Studies 3:1/2. 5–14.

- MacAulay, Maggie, and Rebecca Visser. 2016. “Editing Diversity In: Reading Diversity Discourses on Wikipedia.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 9 (May).

- “Mary Richmond.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- Mattern, Shannon. 2015. “Wikipedia + Feminist Epistemology, Take 2 (Babycastles Remix).” Words in Space (Apr 29).

- New York Times. 2011. “Where Are the Women in Wikipedia?” (Feb 2).

- Paling, Emma. 2015. “Wikipedia’s Hostility to Women.” The Atlantic (Oct 21).

- Peake, Bryce. 2015. “WP:THREATENING2MEN: Misogynist Infopolitics and the Hegemony of the Asshole Consensus on English Wikipedia.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 7 (April).

- “Racial Bias on Wikipedia.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- Raval, Noopur. 2014. “The Encyclopedia Must Fail! – Notes on Queering Wikipedia.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 5 (July).

- Reagle, Joseph, and Lauren Rhue. 2011. “Gender Bias in Wikipedia and Britannica.” International Journal of Communication 5:0. 21.

- Senier, Siobhan. 2014. “Indigenizing Wikipedia.” Web Writing: Why and How for Liberal Arts Teaching and Learning (Aug 15).

- Smith, Bonnie G. 2000. The Gender of History: Men, Women, and Historical Practice. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- “Sophonisba Breckinridge.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- Wadewitz, Adrianne. 2013. “Wikipedia Is Pushing the Boundaries of Scholarly Practice but the Gender Gap Must Be Addressed.” Impact of Social Sciences (Apr 9).

- Wajcman, Judy, and Heather Ford. 2017. “‘Anyone Can Edit’, Not Everyone Does: Wikipedia’s Infrastructure and the Gender Gap.” Social Studies of Science 47:4. 511-27.

- “Wikipedia:Notability.” 2017. Wikipedia.

- “Wikipedia:WikiProject Countering Systemic Bias.” 2017. Wikipedia.

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed  mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”